With a new book on the way this October, it’s been announced that Asterix, one of the most beloved comic book series in the world, is moving to Sphere, at the Little, Brown Book Group.

The team will be taking over the publishing of all Asterix titles from Hachette Children’s Group from 1st July 2021, including all 38 albums and 12 omnibus editions.

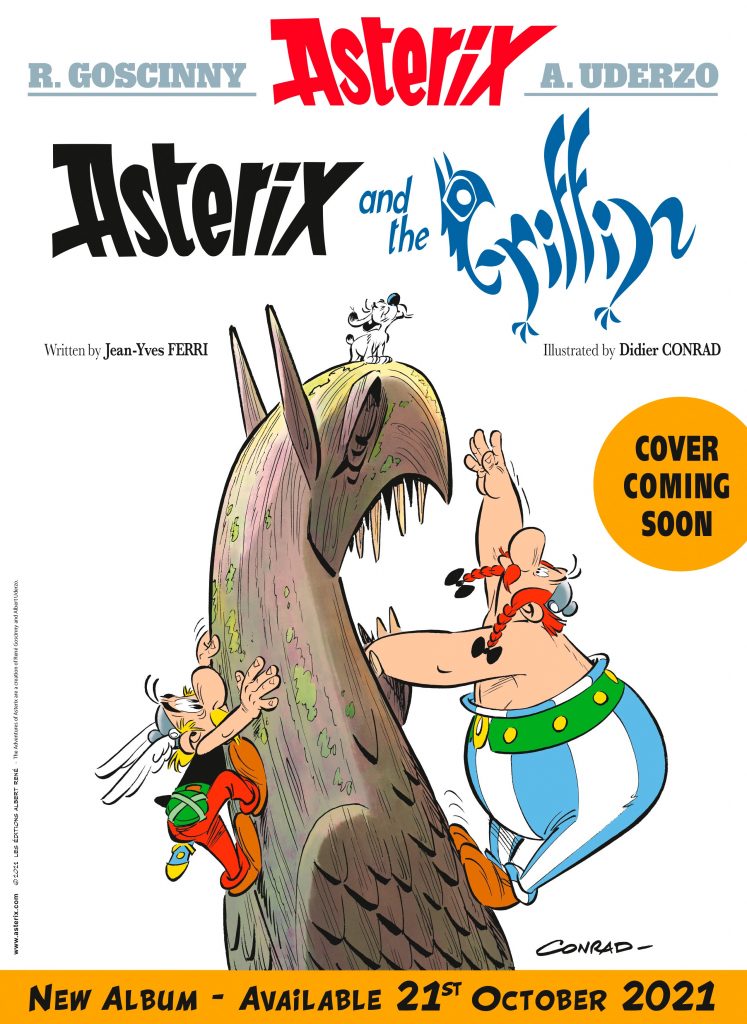

Sphere will also publish the latest book in the series, Asterix and the Griffin, in hardback and ebook on 21st October 2021.

The move to Sphere is in recognition of the brand’s broad and loyal family readership, including Asterix’s dedicated adult fanbase.

Asterix needs no introduction to downthetubes readers. Since the first Asterix album was published in 1961, the series has become a global phenomenon, translated into more than 100 languages and dialects, and sold more than 385 million copies worldwide. Focusing around the adventures of the Gaulish warrior Asterix and his friend Obelix, the series has spawned animated cartoons, 15 feature films and its own theme park, Parc Astérix. The last album, Asterix and the Chieftain’s Daughter, sold more than five million copies worldwide.

Jean-Yves Ferri and Didier Conrad took over the Asterix series in 2013, taking over the creation of new stories from the series’ original illustrator and co-creator, Albert Uderzo, who had been overseeing the series until his death in March 2020, following the death of the books’ original author, René Goscinny, in 1977.

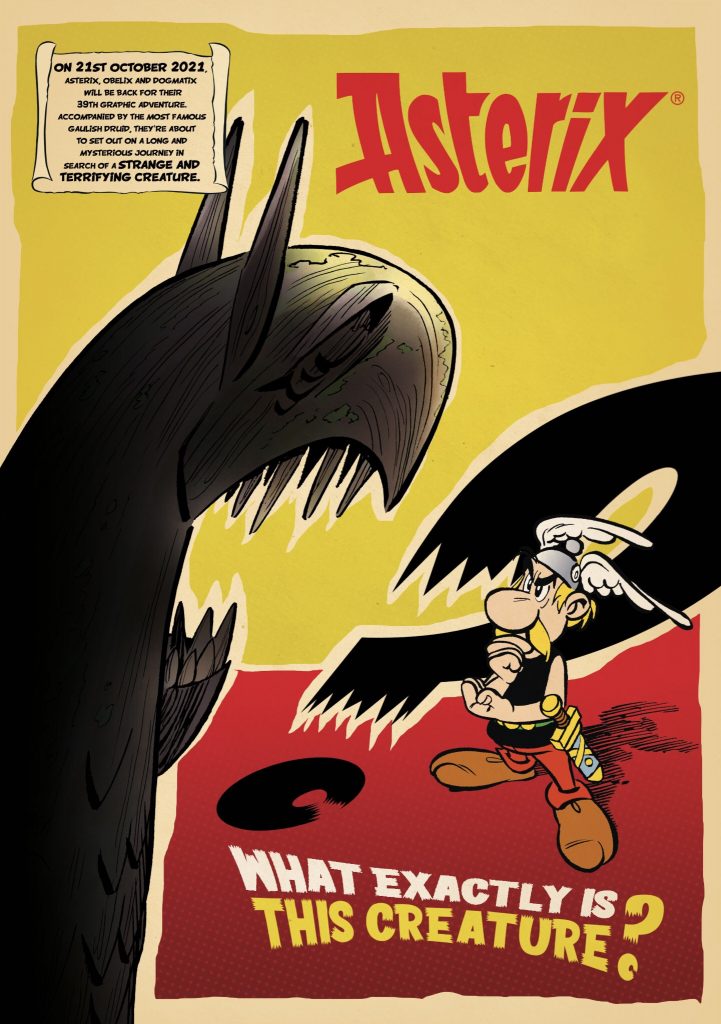

The latest story will see Asterix and Obelix set out on their 39th adventure, and travel to a new destination in search of a strange and terrifying creature, idolised and feared by ancient peoples – the griffin.

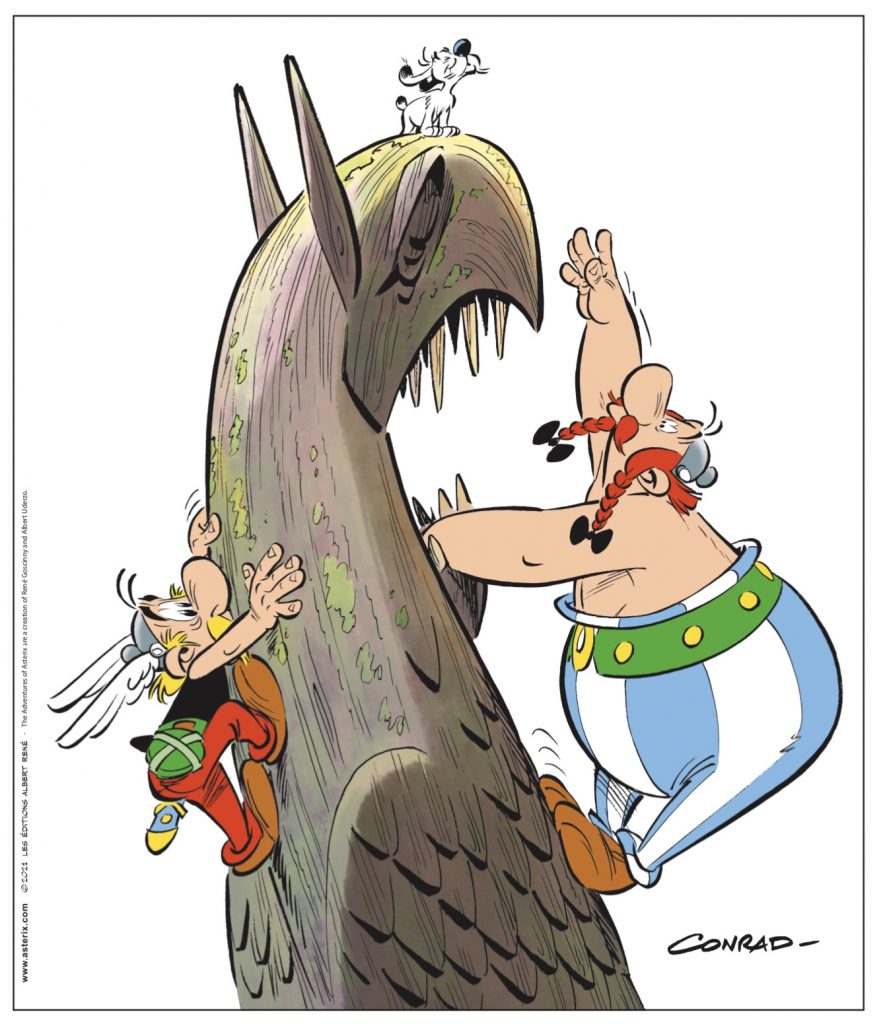

The new book has been teased with a strange and mysterious drawing, sent to Asterix’s French publisher, Éditions Albert René, by Didier Conrad.

It features our two heroes, Asterix and Obelix, scaling a huge tree trunk in an attempt to reach Dogmatix who seems to be trying to get away from them. Is the little Gaulish canine making a bid for freedom?

The trunk is very unusual because it’s carved into an effigy of an enigmatic creature – with impressive teeth and a raptor’s beak …

“For me, it all started with a sculpture of the Tarasque, a terrifying creature from Celtic legends,” explains Jean-Yves Ferri of the new adventure’s origins. “Did our ancestors really believe that these peculiar monsters actually existed?

“It’s worth mentioning,” he continues , “that in Roman times, there weren’t many explorers so the terra was mostly incognita. Even so, extraordinary animals such as elephants and rhinoceroses had already been exhibited in Rome. Having seen them, why would Romans have any reason to doubt the existence of equally improbable creatures? And hadn’t some of them (medusas, centaurs, gorgons …) been described very seriously before their time by the ancient Greeks?

“Now it was time look at this bestiary and choose the animal that would be at the centre of the intrigue. Half-eagle, half-lion, with horse’s ears and appropriately enigmatic – I opted for a Griffin!

“The Romans were bound to go for it. But what about the Gauls? How would Asterix, Obelix and Dogmatix, along with the Druid Getafix, get drawn into the epic, perilous quest to find this fantastical animal?”

That’s what you’ll find out in the new album. And I’m not going to do what Wikipedia does and tell you everything about it …”

The announcement of the title of this new album comes a year after Albert Uderzo’s death,

“Albert trusted us to respect the values of the characters he created with René Goscinny by taking them on new adventures,” note Jean-Yves and Didier. “In his absence, it’s very emotional for us to continue the work he entrusted to us by publishing this new album, which we hope will be a joy to readers.”

As we previously reported, in addition to the new album, Asterix is also due to star in a 3D Netflix animated series, directed by Alain Chabat, who previously wrote and directed 2002’s Mission Cléopâtre, the most successful of Asterix’s numerous appearances on screen and the third highest-grossing feature film in French history. The series will be adapted from one of the classic volumes, Asterix and the Big Fight, where the Romans, after being constantly embarrassed by Asterix and his village cohorts, organize a brawl between rival Gaulish chiefs. The series will debut in 2023, and will be screened around the world.

• Pre-order Asterix and the Griffin from AmazonUK (Affiliate Link)

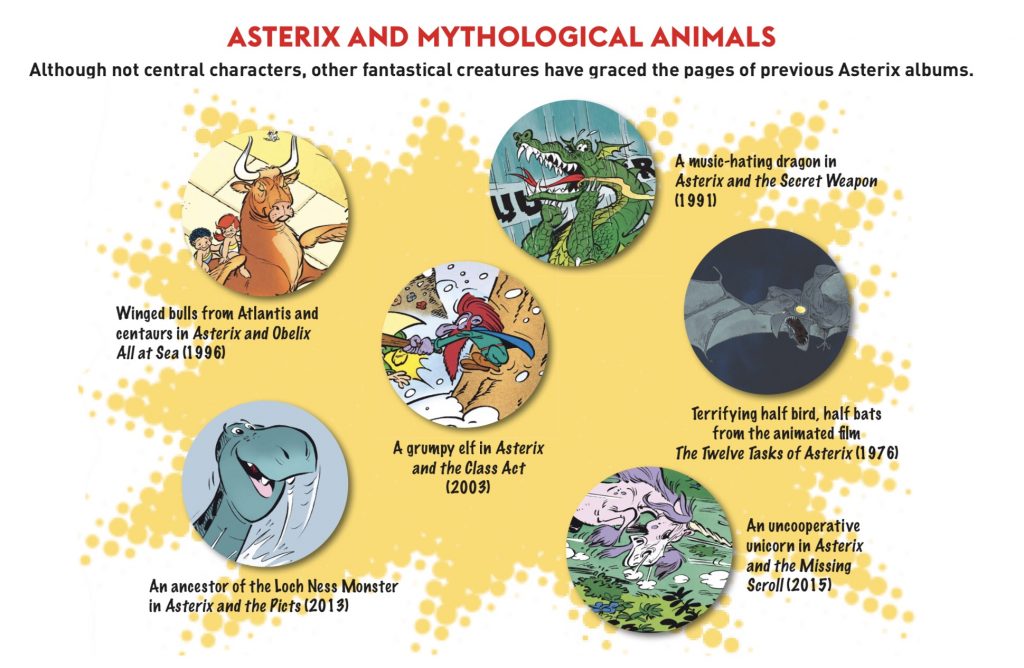

ASTERIX AND MYTHOLOGICAL ANIMALS

Although not central characters, other fantastical creatures have graced the pages of previous Asterix albums…

• Winged bulls from Atlantis and centaurs in Asterix and Obelix All at Sea (1996)

• A music-hating dragon in Asterix and the Secret Weapon (1991)

• Terrifying half bird, half bats from the animated film

The Twelve Tasks of Asterix (1976)

• An ancestor of the Loch Ness Monster in Asterix and the Picts (2013)

• An uncooperative unicorn in Asterix and the Missing Scroll (2015)

• A grumpy elf in Asterix and the Class Act (2003)

THE GRIFFIN IN ANTIQUITY

By Hélène Bouillon, conservator at Le Louvre-Lens and a doctor of Egyptology

As an expert in the relations between Ancient Egypt and the Middle East, Helen is currently co-curator of the exhibition The Tables of Power at the Louvre, and is planning a project based on fantastical animals.

What do Griffins look like? Where do the first traces of them appear?

Griffins are mythological creatures swathed in mystery. And that’s been going on for 5,000 years! They have a lion’s body and the talons, wings and beak of an eagle. The first signs of them were found in Iran, stamped onto clay: imprints of seals that date back to about 3,500 BC. In the absence of mythological texts, no one knows the exact significance of these images, but we know that they were widespread because, at about the same time, a winged lion with an eagle’s head was represented on a sculpted cos- metic palette in Egypt.

Experts believe – but can’t be sure – that the Griffin repre- sented the raw power of nature because it appears alongside other animals, some powerful but real (such as lions and bul- ls), others fantastical (such as half-snake, half-panthers).

In the second millennium BC, images of Griffins appeared in the Levant and Ana- tolia as well as Cyprus where they fea- tured in carved ivory plates decorating royal thrones and beds, and were depic- ted in a seated position with their wings spread and a crest on their heads. Throughout this period, they travelled thanks to

trading links, transported on Canaanite boats to the shores of Palestine, Syria and Lebanon, then in the first millen- nium BC, they spread to the Phoenicians and Greeks and to the Black Sea region where they were used to decorate weapons and furniture of nomadic peoples such as the Scythians.

In Ancient Greece, Griffins were portrayed guarding the trea- sure of Apollo and Dionysius. In the same period, the Persian Achaemenid Empire used them for decoration in palaces. They’re also found on thrones and luxury tableware from the Phrygian and Lydian kingdoms in Anatolia.

What is their role in mythology? What do they symbolise?

The symbolism of Griffins evolved as they travelled and were adopted by very di- verse civilisations. They symbolise power (a lion’s body), vigilance (an eagle’s pier- cing eyes) and ferocity (the bird’s talons and sharp beak). To the Egyptians, Griffins symbolised victorious kings – archaeologists have mostly found them in places associated with royal circles, namely temples close to the pyramids that date back to the third millennium BC. Gold pectorals (necklaces) from the second millennium BC also represent the king in the form of a Griffin slaughtering foreigners.

Lastly, we have the Greek language to thank for the word Griffin (in the fifth century BC); it means ‘curved’ or ‘hooked’.

How are they represented after ancient times? What legacy do they have in modern history and art?

Interestingly, ever since those first traces were found in Iran, Griffins have always had the same head but, with their constant peregrinations, they’ve tended to change what is on their heads. So, in the first millennium BC, they had pointed ears like Mesopotamian demons, and they’re still represented in this way in Medieval bestiaries.

In the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, they featured in a number of coats of arms. In travel writing, such as the work of Marco Polo, we’re told that huge Griffins were seen in India and Ethiopia, and that they could carry elephants in their talons; they would then drop them mid-flight and swoop down to devour them.

The common ground between all these legends is that these mythological ani- mals were powerful and dangerous, fea- red and respected.

As for the statue of a Griffin in the visual for Asterix and the Griffin, it perfectly matches how they were represented in the first millennium (a representation adopted by the Greeks and all Mediterra- nean nations to this day), because it has inherited those small, pointed ears. And here’s the surprise … it looks as if this is the largest sculptural depiction of a Griffin ever found!

• Pre-order Asterix and the Griffin from AmazonUK (Affiliate Link)

The founder of downthetubes, which he established in 1998. John works as a comics and magazine editor, writer, and on promotional work for the Lakes International Comic Art Festival. He is currently editor of Star Trek Explorer, published by Titan – his third tour of duty on the title originally titled Star Trek Magazine.

Working in British comics publishing since the 1980s, his credits include editor of titles such as Doctor Who Magazine, Babylon 5 Magazine, and more. He also edited the comics anthology STRIP Magazine and edited several audio comics for ROK Comics. He has also edited several comic collections, including volumes of “Charley’s War” and “Dan Dare”.

He’s the writer of “Pilgrim: Secrets and Lies” for B7 Comics; “Crucible”, a creator-owned project with 2000AD artist Smuzz; and “Death Duty” and “Skow Dogs” with Dave Hailwood.

Categories: downthetubes Comics News, downthetubes News

Christophe Chabouté in the spotlight at Maison de BD

Christophe Chabouté in the spotlight at Maison de BD  New book charts the history of groundbreaking French comic magazine, Pilote

New book charts the history of groundbreaking French comic magazine, Pilote  Sizzling Summer Days ahead with a “Sideways Universe” 2000AD Sci-Fi Special on the way!

Sizzling Summer Days ahead with a “Sideways Universe” 2000AD Sci-Fi Special on the way!  A haunted tank and a jinxed pilot offer a supernatural twist in new Commando comics

A haunted tank and a jinxed pilot offer a supernatural twist in new Commando comics