In September 2014, comic creator Neill Cameron published a series of articles on the British comics industry which he has very kindly given us permission to cross post here, as part of wider efforts by both him and many others to promote comics in the UK. We’re grateful to Neill for the chance to re-circulate this series of articles.

Booktrust and Save The Children recently launched their Read On, Get On campaign; spreading awareness of a crisis in literacy rates, aiming at a target of every child leaving primary school to be able to read well by 2025, and calling on politicians of all parties and indeed the general public to do all they can to support this crucial goal.

I – obviously – applaud this initiative, and support its aims entirely. It’s prompted a lot of discussion amongst the kind of people I follow on Twitter, and I wanted to try and organise here in some semi-coherent fashion my thoughts on the role comics have to play in all this. Because I think comics can be a huge part of the solution to falling literacy rates. And indeed, I think their disappearance in the last 20-30 years from their previously central space in children’s lives in this country may well be a part of the reason for that crisis.

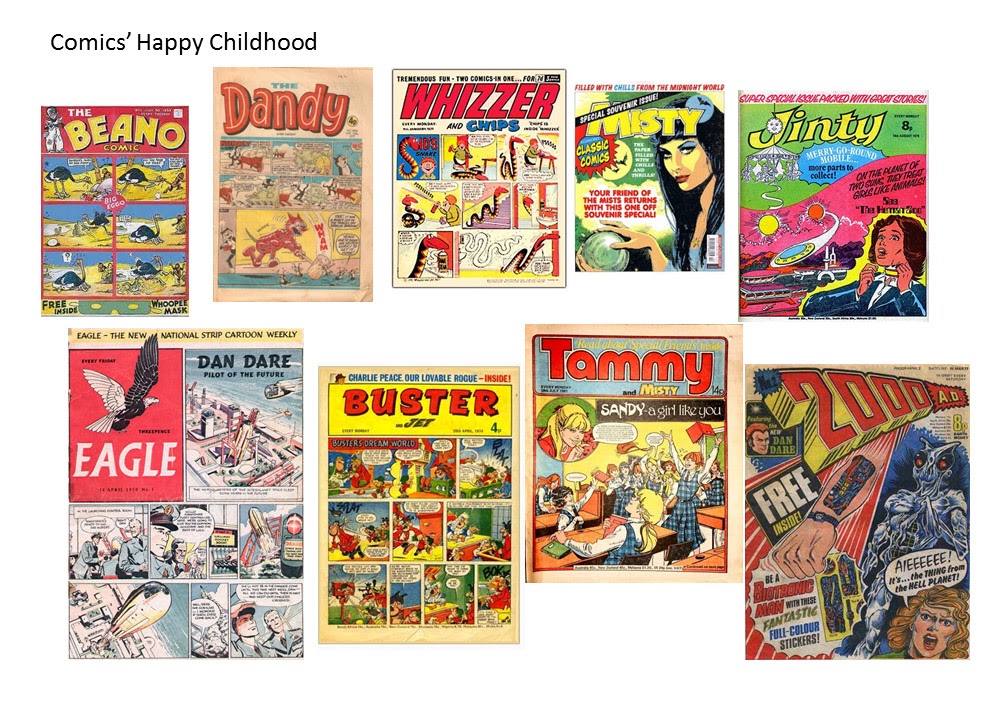

I’ll kick things off in the traditional way when examining social problems: by sounding like an old man and moaning about how much better things were In My Day. (There’ll only be a bit of this, I promise.) The role comics played in the childhood of many of my generation, and even more so the further you go back, was huge – and in hindsight, crucial. Comics were everywhere, and often free – stacks of them lying in ‘rainy day’ chests at school, at clubs, at mates’ houses, in dentist’s waiting rooms. There’d be a bunch to choose from and even if they didn’t have any of your favourites, what the heck, they were still comics right? And there was always a fresh crop to be had every week anyway, from every newsagent and corner shop in the land, at prices realistically within the realm of pocket money while still maybe even leaving enough change for a bag of Skips.

I’m honestly not just going to wallow in nostalgia here, mourning for some lost Golden Age of Kids’ Comics. I just wanted to outline a few of the key aspects of that situation, to highlight the differences between where we were and where we are now. Namely:

- RANGE. This barely needs stating, right? We all know this? There used to be a huge range of children’s comics widely available across the country, and now there is The Beano. I’m simplifying slightly, but not much. A wider range is out there, of course. There are many, many people making genuinely great comics at the moment, but I think it is fair to say they simply are not on the cultural map of the vast majority of the population. They’re not in WH Smiths, or your corner shop, or really any place a kid is likely to be going on a weekly or more regular basis.

- AFFORDABILITY. Most comics, these days, are not easily within the Pocket Money Affordability Range. And there are reasons for this, sure, in terms of printing methods and rising production values and distribution models and what have you. But the end result is: comics that you are not going to be able to buy a couple of and still afford a bag of Skips.

- (Do they still make Skips?)

- (Am I just not giving my kid enough pocket money?)

- Anyway, these two factors in part explain and contribute to the main difference, which is:

- ACCESSIBILITY. Comics used to be around – very easy to encounter and get in the habit of reading, without having to particularly set out to do so. And now, by and large, they’re not. They were the water in which we swam, and now they are a remote legendary spring on a mountainside somewhere. They’re still there, but only for the seekers and the kids whose parents can afford nice houses up on top of the mountain. The majority, sadly, probably aren’t going to make the trip.

So, how did we get here? And does it matter? Do comics still have any relevancy to children, anyway? Haven’t we ended up in this reduced state because kids simply stopped caring about comics, moving onto video games and Minecrafts and blah blah whatever we’re all supposed to be worried is ruining kids this week?

Firstly, let’s just demolish any hint of a pretence that ‘do kids still like comics?’ is even a question. I could throw any amount of anecdotal evidence at you from myself and other comics creators who work with schools and libraries and children’s literary festivals, anecdotal evidence that would border on “evangelical”. Or alternatively, you could just look at the extraordinary sales figures of children’s comics and graphic novels in other parts of the world. Children still like comics, to the best of my knowledge, in Japan and Europe and India and every other damn place. Raina Telgemeier sells 7 gajillion copies of every new comic she makes in the US. So let’s just knock that on the head. Children still like comics. They love comics, when they get a chance to actually read some. So how did we reach this point where that’s no longer happening in this country?

How We Got Here

There are essays and opinion pieces and twelve-volume histories to be written on that point, and I don’t want this to descend into negativity and accusations and recriminations. But I do think it’s worth taking a second to address it here, as part of demolishing the aforementioned ‘do kids still like comics?’ not-even-a-question. Personally, I think there’s a couple of factors that help explain it:

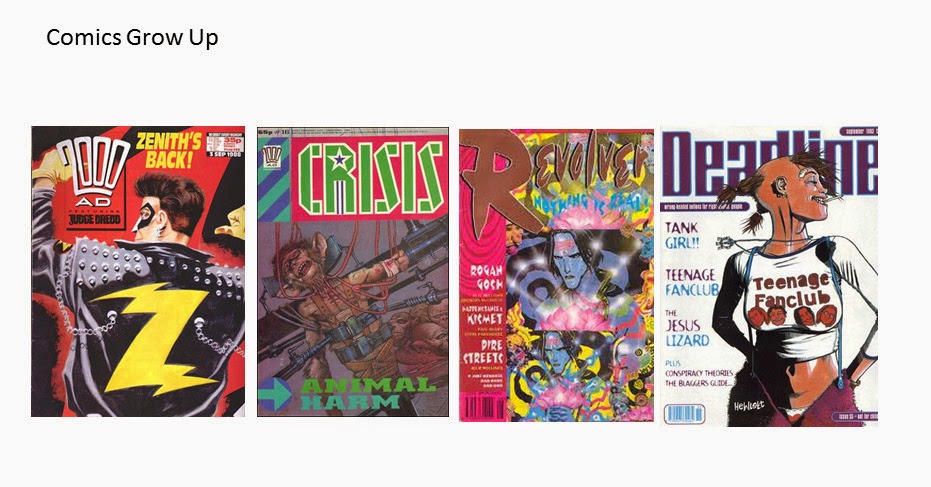

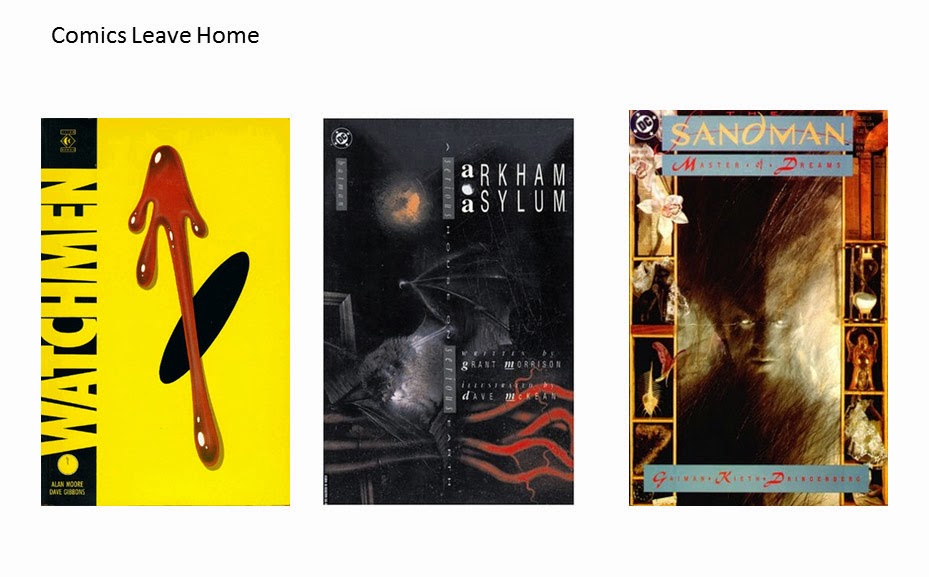

- a resource drain from both the UK and the field of children’s comics, as both creators and publishers chased after new markets and artistic legitimacy by competing to show who could make the most ‘mature’ works. (‘Mature’ in this sense meaning, broadly speaking: stories about Batman dealing with erectile dysfunction)

- the increased focus of the remaining newsstand UK titles on expending resources and budget on the bit of plastic stuck to the front of the comic, rather than what’s inside the comic.

Again, don’t want to get too negative here. Free gifts are awesome! Who doesn’t like free gifts? And demonstrably, you will sell more issues of a particular comic if you stick a plastic laser gun and a bag of sweets to the front. But those free gifts aren’t really free, are they? They cost money somewhere along the line. And ultimately, if they come at the expense of making actual jokes and stories and awesome comics that engage kids’ imaginations – well, yeah, maybe you’ll sell more issues of that particular comic. But I would argue that you are unlikely to make a generation of kids fall in love with reading.

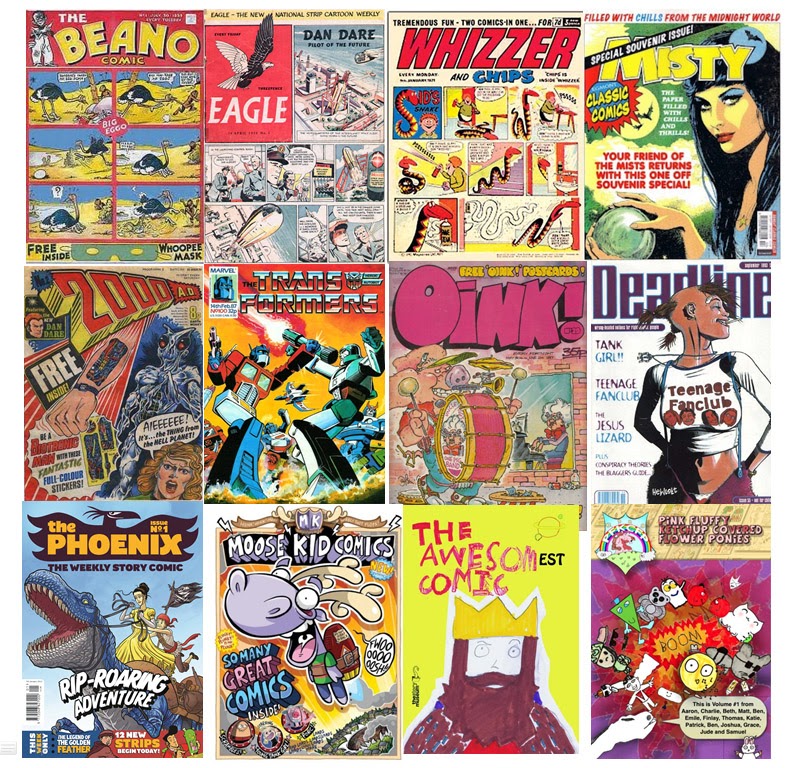

I was giving a talk to teachers and librarians recently on this subject and I put together a few slides as a visual aid. They’re abbreviated and simplistic, and no doubt horribly unfair, but hey. It made me laugh?

A (Somewhat Abbreviated) History of British Children’s Comics

1:

2:

3:

4:

(Cover images blurred to protect the innocent. And also, because, honestly, I’m not trying to be a COMPLETE ass here. I just needed a punchline?)

So there you go, that’s (my biased, arbitrary, possibly communist opinion on) How We Got Here. To turn to the second question:

Does It Matter?

Yes, it matters.

There we go, that was easy. But seriously, it really does.

I’ve been thinking about this lately, about why we’re all doing this – those of us that make comics, and love comics, and try to spread the word of comics. Is it just because we loved them as kids, and want to see the medium continue? Because if that’s all it is, just a nostalgic self-absorbed desire to recreate our own childhoods, then frankly we should just call the whole thing off and all go home and eat a bag of Skips. It’d be cheaper and just much less hassle all round. But it’s not that. Comics matter, for all the reasons that reading matters. Learning to read makes a tangible, measurable difference to children’s lives and prospects, in terms of economic outcomes and quality of life. And comics are – have been, can be, will be again – a huge part of learning to read. Of reading for pleasure; of coming to love reading; making it not something that is enforced from above, a Discipline That Must Be Mastered, but something so exciting and cool and mind-blowingly awesome that it has to be torn out of kids’ hands when it’s time to go to bed.

And if any part of you is wondering if this is still true, if children still have that response to comics, then let me put your mind to rest right now: they do. They absolutely do. Comics perform a fantastic dual purpose:

- providing kids with a visual narrative that they can follow and engage with while their verbal literacy skills are still developing, thus encouraging the development of those skills

- offering unique opportunities for exciting subject matter that can hook kids imaginations, lending itself to strong visuals. Robots! Dinosaurs! Mutant rabbits with laser nunchuks! COMICS.

When kids actually get to see comics, when they are given exciting stories and phenomenal artwork and funny jokes about beavers doing a radioactive poo, they flip out. They dive in with both feet and get lost and fall for comics so hard that it alternately makes me inspired and delighted and, actually, angry.

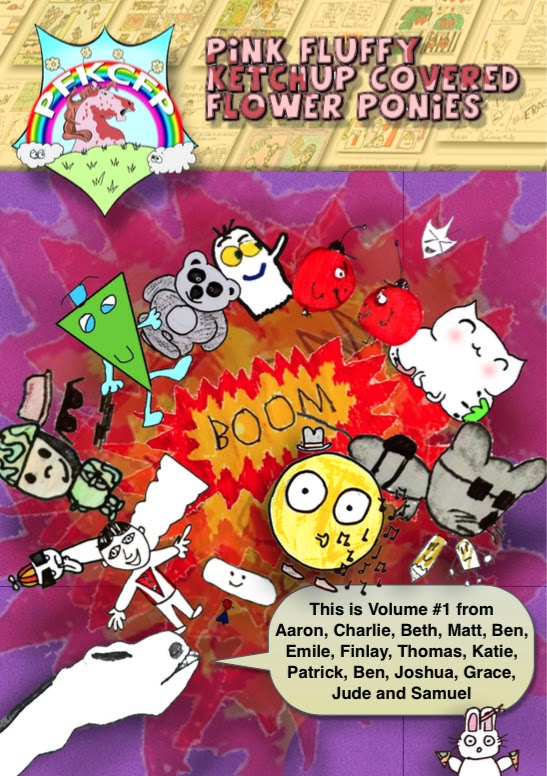

Angry because I’ve seen, first hand and over and over again, just how much enjoyment and hilarity and genuine learning and TANGIBLE INCREASES IN READING DEVELOPMENT kids get from comics like Corpse Talk, or Dungeon Fun, or Moose Kid, or Star Cat. And because I know, all too well, that those comics are not a part of the lives of the vast majority of children, right now. They’re not in the corner shop, they’re not in big rainy day trunks at school, they’re not in the dentist’s waiting room. They are, to generalise wildly, the province of a privileged few: those with parents who can afford them and have even heard of them in the first place. All of which immediately limits your reach down dramatically to a pretty small circle of ‘in the know’ people. And whilst I love those people to bits and indeed am one of them, I think we can all agree it’s not enough. We need to break past that circle, to explode the art form outwards and back to where it should be; an available, accessible, affordable part of the lives of all children.

I’ll be posting more on this subject every day this week, including some actual ideas and concrete proposals on how we actually, y’know, DO that. But first, tomorrow: the BEST way comics can help develop children’s literacy, which I haven’t even mentioned yet.

Neill Cameron is a cartoonist and writer, creator of the young adult graphic novels Mo-Bot High and the instructional How To Make Awesome Comics. Since 2011 his work has appeared in the weekly children’s comic The Phoenix, where he produces – amongst other things – the dinosaur adventure serial The Pirates of Pangaea (with co-writer Daniel Hartwell), the robotic soap opera comedy Mega Robo Bros, and (with artist Kate Brown) the Cornish-set fantasy drama Tamsin and the Deep.

Neill is also currently artist in residence at The Story Museum in Oxford, where he has contributed several large-scale comic strip installations and is involved in comics-based education and activities.

Neill frequently travels the country giving workshops in schools, libraries and at festivals, and is a passionate advocate for the role comics can play in fostering literacy and encouraging children’s creativity.

One of many guest posts for downthetubes.

Categories: British Comics, Comics Education News, Creating Comics, Featured News, Features

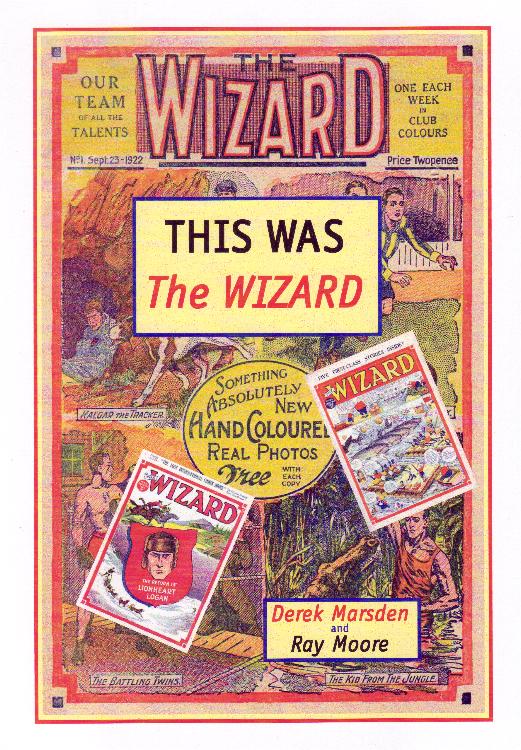

In Review: This Was The Wizard

In Review: This Was The Wizard  Comics and Literacy, Part 5: Where Do We Go From Here? by Neill Cameron

Comics and Literacy, Part 5: Where Do We Go From Here? by Neill Cameron  Comics and Literacy, Part 4: Comics For 7-Year-Olds by Neill Cameron

Comics and Literacy, Part 4: Comics For 7-Year-Olds by Neill Cameron  Comics and Literacy, Part Two: The (New) Golden Age of Children’s Comics by Neill Cameron

Comics and Literacy, Part Two: The (New) Golden Age of Children’s Comics by Neill Cameron

Good article, and I hope it gets as wide a hearing as possible – but without that simplistic and horribly unfair History of British comics, which is vastly more than ‘somewhat abbreviated’ and heavily slanted towards the 70s/80s.

How so? Well, other than the obligatory Dandy and Beano, there is little pre-1950 and nothing at all to show comics were being published for 60 years before the 1930s! Whole genres have disappeared: where are the undergrounds, the boys’ adventure titles (apart from The Eagle), the TV and radio tie-ins, the funny animal comics, the horror comics? Where are Ally Sloper’s Half Holiday (1st British comic with a recurring character), Roy of the Rovers, Rupert Bear or The Boys’ Own Paper (ran for 88 years)? Anyone looking at the slides might wonder why the ‘happy childhood’ era ran for 100 years but both the ‘grow up’ and ‘leave home’ sections took place over a few short years in the mid- to late 80s? And how do any of the three American publications in the ‘leave home’ section qualify as British comics?!! Worst of all, there is no timeline and little visual sense of the diversity of comics.

Seriously, you (rightly) talk to teachers and librarians about the importance of comics and literacy – but then undermine it with a narrow, misrepresentative history of the medium based on ‘It made me laugh’…? Comics can be funny, yes, but they can be so much more than that.

Shame.

Hi Alan, to be fair to Neill most people visiting this web site are well aware that British comics have a huge and very rich history and the graphics may well not reflect that – but even utilising the small number of comics Neill chose to feature, the graphics do indicate, if only fractionally, what has been lost. But I’d happily love to see a brief history of British comics decade by decade on dwonthetubes if someone such as yourself had time to contribute it?

Heh – a very diplomatic ‘put up or shut up’?! I love the idea and the challenge. Time is very tight with me these days but I will do my best. Time to see if my new iPad will make a viable work tool.

I must take you up on one point though: you said “to be fair to Neill most people visiting this web site are well aware that British comics have a huge and very rich history.” True, but Neill said he put together the slides as a visual aid when talking to teachers and librarians – ie people who may well not be aware of that history.

My point was that, while his words in the article were well chosen, the selection of images for the slides was anything but.

And now, if you’ll excuse me, I have a history to start researching…

PS I’m not very tech-minded, so I don’t know why my name appears here as hellomabel (my eBay tag) or indeed how to change it to my real monicker (Alan Woollcombe, in case anyone was wondering).

Hi Alan, feedback on articles we post on downthetubes is ALWAYS welcome, especially from someone as erudite as you good self.