Photo by José Villarrubia

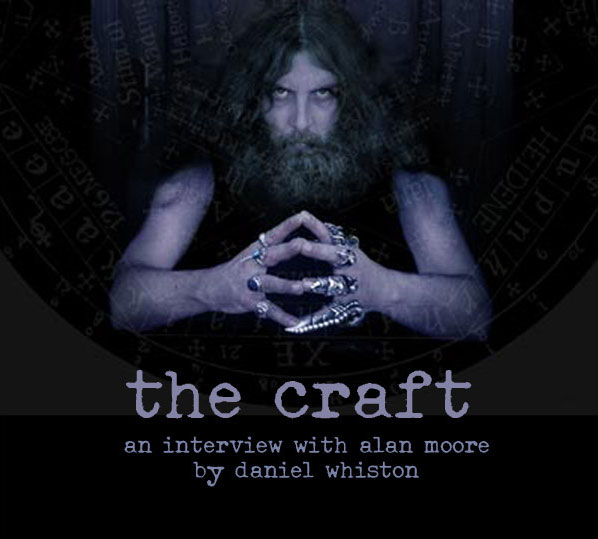

First published on the Engine Comics web site way back in 2002, this is the second part of a wide-ranging interview with Alan Moore specifically about writing comics with Daniel Whiston is a fascinating read, and is re-published here on downthetubes with permission of the interviewer. You can read Part One, which we re-published last year here

Aside from Alan’s advice on writing comics, the interview touches on his views, then, on digital comics, what DC might do with Watchmen without him, and other topics that make for an interesting look back at the work of this much-respected author, talking at the turn of the century…

Part Two: 29th October 2002

Having been graciously invited to his Northampton abode by the World’s Greatest Comics Writer, myself (Daniel Whiston) along with David Russell and Andy Fruish had a long and fascinating meeting with the Enlightened One, surrounded as we were by shelves groaning under the weight of books and comics, walls covered with mystic paraphernalia from throughout the ages, and a constant fug of smoke.

Having already met Alan in September, David Russell and I returned to the Moore-cave in October for a second fix. Once again Alan welcomed us with by now customary cups of tea into his inner sanctum. We cracked open the Dictaphone, and got down to business…

Alan: What questions can I answer about The Craft for you?

Daniel Whiston: Last time we talked about the “toolbox”: if you’re gonna be reductionist about it, plot –

Alan: Different areas of creative importance.

Daniel: What I thought might be interesting to talk about this time was a more type of ‘reportage’ perspective: when you sit down to write a comic, is there an experience that is common to those different projects, those different pieces, those different works, that seems to come out over time? How does one start? I mean, this is a naïve question, but do you start with a fragment of dialogue, or an idea, or –

Alan: Well, a story can start with anything. It can start with a fragment of dialogue, it can start with a sudden idea for a character, it can start with a purely intellectual musing upon some subject or other – the thing that unites all of these things is the endless frozen tundra of an empty page. This is the theme whether you’re talking about writing a performance piece, a comic, a novel, whatever.

Daniel: I think we’re talking about something from nothing.

Maxwell the Magic Cat was both written and drawn by Alan and appeared in the Northants Post. © Alan Moore

Alan: Yeah, this is the essential mystery of creation whether you’re talking about an individual act of creation such as writing a poem, a story or a comic or whether you’re talking about the creation of the universe. It’s all something from nothing. You could say the same thing about thoughts entering our heads. Ideas. There’s that white page somewhere there at the beginning of the process, whether you’re talking in cosmological terms where the white page is the quantum vacuum. If you’re a novelist then it is literally a white page.

Now, what you have to do is limit yourself. You cannot work in a complete conceptual void. Which is what the white page is. You have to start putting restrictions upon yourself. Now, if you’re working commercially then you’re lucky, in a way, because some of those restrictions will be pre-imposed. If you’re asked to write a half-page story for a comic anthology – 2000AD – then you know certain things about the story, there are certain parameters. You know it’s gonna be something in the kind of science fiction/ fantasy area, so the genre is already imposed. You know it’s gonna be, say, five pages long, which means that’s probably 30 panels, tops, maybe a few more, a few less, but that’s roundabout what you’re looking at.

These are all kinds of structural considerations which give you somewhere to start. They kind of mess up the white page, interestingly. Now you can then, I find, often achieve interesting results by… once you’ve got your initial start conditions, once you’ve got your basic shape – you know it’s a five-page comic strip about science fiction – or a five- panel comic strip about a cat – a one-hour performance piece about William Blake – you’ve got your purely external parameters imposed – then, what is productive very often is to immediately come up with a bunch more shackles with which to bind yourself.

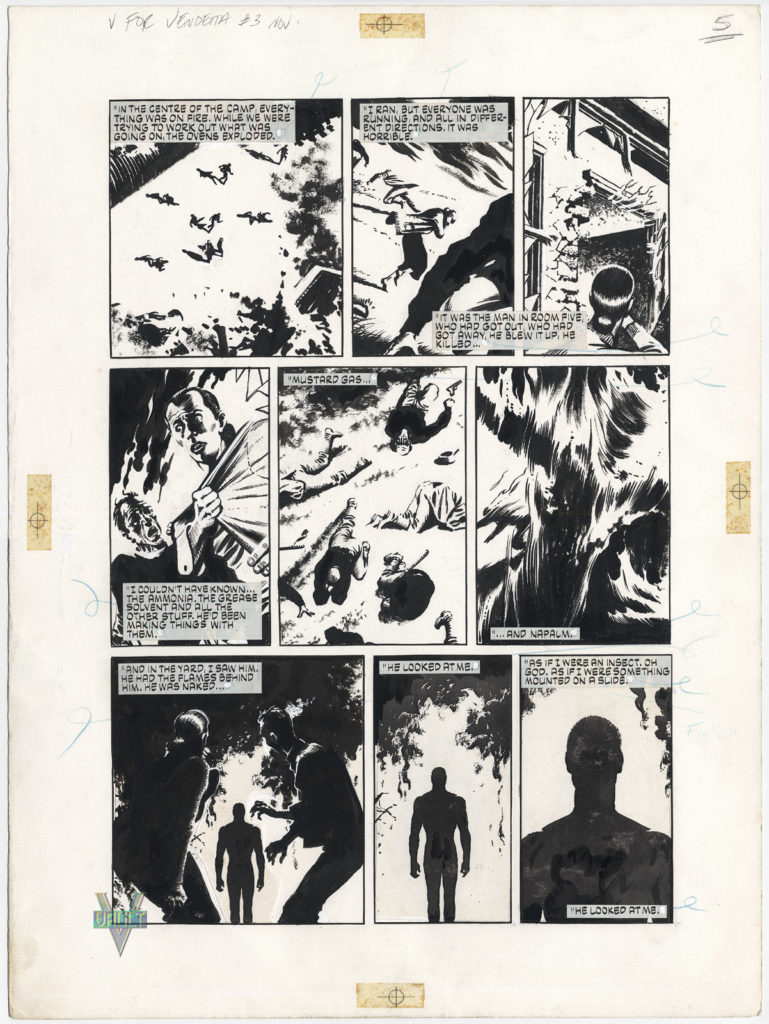

Start imposing ridiculous little rules, just perhaps on a whim, or because you think they might help. You don’t have to be too logical about this, although logic can help. I mean, as an example, when I was starting to write V for Vendetta, David Lloyd, the artist on the strip –

Daniel: At this point, if we pause the tape, can you tell us who V really is?

Alan: Erm – no, I’m afraid. ( laughter ). If I knew, I would. But… V’s exactly what he looks like: he’s an idea, with a mask and a hat and a cloak. He’s much more symbol than reality. When we were doing that, David, at the outset, said that he’d got a feeling that comics would be better without sound effects and without thought-balloons.

He made a very cogent case for this; he said that in real life, or in cinema, we don’t have the luxury of knowing what people are thinking, we can’t see a little cloud above peoples heads, we don’t have access to their inner life. Now in literature we do, but I could see his point. I could see that there was something about thought-balloons which distanced the story from immediate reality.

Original art for V for Vendetta by David Lloyd

Daniel: Maybe in a sense literature makes you God, you can know everything, or often books are written as though you know absolutely everything that’s going on unless they’re a mystery, whereas other mediums are more observatory…

Alan: I’d got rid of the sound-effects, I’d got rid of the thought-balloons and I started to think well probably I could do with getting rid of the captions as well. I didn’t completely banish captions until From Hell, which was very very restricting, and that’s one of the reasons From Hell was so long.

Daniel: Do you think that had an impact on the density of the footnotes?

Alan: It probably did – well that was mainly due to the nature of From Hell, in that it was a kind of historical reconstruction, so the footnotes seemed necessary to me. But it certainly added to the length, because when you’re not using things like captions or thought-balloons for exposition, yes that’ll give you greater verisimilitude, greater reality in the story that you’re telling. People won’t have so many barriers that are placed between them and complete identification with and immersion in the story.

At the same time, it will take you two or three pages to do what you could have done in a few panels if you’d been using captions.

David Russell: Surely it can be better, like in the first version of Blade Runner, where they’ve got the voice over…

Alan: Oh, well that was always rubbish… I mean it was using a comic-book technique, and not very well – because it didn’t actually add that much information to the scenes, except to the impenetrably dim members of the audience –

David Russell: And as you were saying any ambiguity destroyed the verisimilitude –

Alan: Yeah, I don’t like voiceovers in films anyway. Much as I’m a big fan of the Coen Brothers, the cowboy narrator in The Big Lebowski was to my mind one of the major flaws of the film – it was a distancing device. Devices like that make it much more obvious to the reader that they are reading a story. If you don’t have those obvious devices, then the reader can get completely sucked in. I suppose at its purest with comics you’re talking about wordless comics – or comics with very few words – where people are drawn into the situation purely visually.

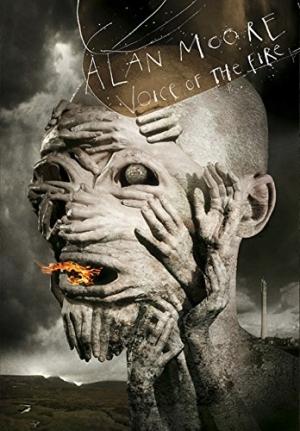

But you can come up with other stylistic limitations that will be to the benefit – generally – of the story. When I was writing Voice of the Fire, the last chapter, for some reason – because it was me narrating it I suddenly got very shy about using the word ‘I’.

But you can come up with other stylistic limitations that will be to the benefit – generally – of the story. When I was writing Voice of the Fire, the last chapter, for some reason – because it was me narrating it I suddenly got very shy about using the word ‘I’.

I think I got a bit self-conscious, I thought I hate it when I read pieces by people and it’s: “I, I, I, me, my”, and I thought, I don’t want this to come over like that – although I am the narrator I want to be kind of invisible, I want to be an anonymous voice. So it’s a first-person narrative without the first person. I don’t use the word(s) I, me, my anywhere – and it’s quite an interesting exercise, it does something to the prose, it leaves a kind of vacuum at the centre of the narrative that the reader can then inhabit. They can become the ‘I’ of the story because there’s no I, me, Alan Moore – there’s no occupying entity in the story, so there’s just a nice space left. But that was a sort of limitation that was self-imposed.

With the first story of Voice of the Fire, I decided to alter the entire language to an approximation of the kind of language I imagined a Neolithic tribesman speaking in. Obviously, it’s in English, but I decided that based on my knowledge of Aboriginal languages, most of them seemed only to have a present tense, they don’t have a past or future tense, they see the past and future as being somehow subsumed within the present. That’s interesting. That’s a different mindset to the modern mindset. And I also decided that they’d probably have a very very limited vocabulary.

I think the vocabulary of the average Sun reader is something like 10,000 words. And I think that the vocabulary of the first story of Voice of the Fire – is around 500? It’s very stripped-down. Which made it very difficult to read, almost incomprehensible to some people – there are some people who never got to read the rest of the book because they couldn’t get past the impenetrable bramble hedge of that first chapter. But it was what I wanted to do, it got the effect that I was after.

So. You impose these preconditions upon the work. Then, when you’ve got a bit of an idea of what you’re going to do, attend to its internal structure. You know what the limits of the perimeter fence are. You know that it’s an hour of performance, or five pages of comics, or whatever. Then break it down. It’s a novel, break it down into chapters, if it’s a comic script, break it down into pages, if it’s a performance piece like one of the Blake pieces, break it down into movements.

Try and understand how the different pieces you’ve broken it down into fit together, what their purposes are, their functions. An easy textbook way of doing this is the kind of standard Hollywood three-act drama, your beginning, your middle and your end where you’ve got plot points placed a third of the way through, two-thirds of the way through and then, the big climax, right at the end.

And yeah, you can see that – you watch most Hollywood films, say they’re about two hours long, then about 40 minutes in, something decisive will happen, and then about 80 minutes in, something that completely turns the story around and that you never expected will happen, and at the end of the film you’ll have the climax, the payoff, where everything will be resolved.

Unless it’s Mulholland Drive and he’s David Lynch and he doesn’t have to follow making f****** sense.

So what you’re doing is, you start out with this white tundra, and then you erect fine and finer, more and more detailed levels of structure. And there’s a certain amount of intuition in that, which is something which is not really quantifiable, but which comes with practice. You’ll start to develop a personal aesthetic as to the kind of shape of the stories that you wanna do. You’ll start to realise that – doing something this way – you can get results, but it’s manipulative. It’s trying to jerk people’s emotions around. And that that doesn’t feel right.

So you’ll kind of modify the way you approach emotional scenes… you’ll perhaps decide that there’s greater power in keeping more in reserve, in soft-peddling, in leaving a lot unsaid. Let it sort of detonate in the readers mind a few moments later. There’s benefits to all these approaches. And they will all shape the thousands of creative decisions that you’re gonna make, probably in the course of even a short work. And then, you know, it’s sort of, er –

Daniel: Sorry to interrupt, but it sounds like you’re saying – to someone who’s not a very practiced creative person – that it’s something to do with clarifying and developing an emotional position on your work, how you interact with those worlds you conjure up, in a way that feels right…

Alan: Well, emotional position is part of it, but as an individual you are not your emotions, neither are you your intellect. These are things that you have . They’re not things that you are . Therefore you have to start to become aware of the different requirements that human beings have, the different areas that they like to be satisfied in.

Daniel: That’s what I meant by becoming aware…

Alan: Yes. Which means becoming aware of yourself. I mean, as a writer, you’re gonna have to understand pretty much the whole universe. But the best place to start is by understanding the inner universe. The entire universe – for one thing – only exists in your perceptions. That’s all you’re gonna see of it. To all practical intents and purposes this is purely some kind of light show that’s being put on in the kind of neurons in our brain. The whole of reality.

So. To understand the universe there’s worse advice than that which was carved above the shrine of the Delphi oracle. Where it just said: “Know thyself”. Understand yourself. Know thyself is a magical goal, but like I say to me there is very little difference between magic and creative art in any sense – the laws of one apply perfectly well to the other.

The Kabbalah in English and Hebrew

Now, coming to understand yourself – again, reductionism is a useful tool. In Kabbalah, you’ve got the lowest spheres of the Kabbalah…

(At this point Alan turns around and is explaining a diagram hung on the wall of the room).

This sphere – the lowest sphere for those who are listening to the tape and can’t see what I’m doing – the lowest sphere of the Kabbalah relates purely to the physical realm – that is the realm of the body and the physical world surrounding the body. We all have a body but we are not – whatever the materialists would have us believe – we are not our body.

The next sphere up is the Lunar Sphere which is related to dreams, fantasy, romance, the imagination – and we all have an imagination, and we all have dreams, but we are not our dreams. They’re a very important part of our makeup just as our body is, but they are not the sum total of us.

This bit over on the left, the bottom of the left hand side of the tree is the Sphere of Mercury, that is the sphere of intellect. We all have intellect and thus our intellect has demands, just as our imaginations do, just as our bodies do.

The opposing sphere on the other side of the tree is the Sphere of Venus. This is to do with emotions and feelings, which we all have. The most important sphere on a human level is the Solar Sphere, which is the column three tiers up. That represents the soul, or the ‘higher self’ if you prefer that sort of taxonomy, the guardian angel, the self, as in ‘know thy self’, I mean the Delphi Oracle, it was an oracle to Apollo who, as the Sun God, goes there (points). What you have to do is develop each of those areas within yourself. Well, another way of looking at it, again using magical terminology, is that in magic it’s said that that you shouldn’t really commence magic until you’ve got your four magical weapons and I’d say yeah, that applies to art as well, it applies to writing.

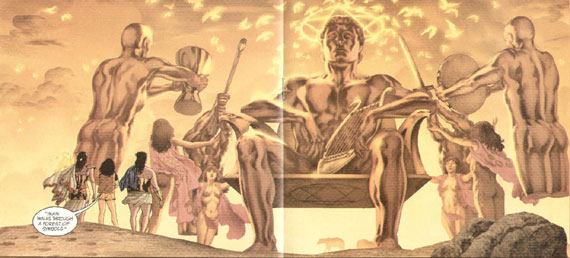

Art from Promethea #17, by J.H. Williams III, Mick Gray and Jeromy Cox

The four magical weapons are the wand, the sword, the cup and the coin. The coin represents the earthly, material things – the body. Yeah, you’ve got to be materially grounded, you’ve got to understand the material world. You’ve got to understand the urges of the flesh. You’ve got to understand how all of this works on a hard, practical, earthly level. You need your coin.

The sword represents intellect and discrimination, both of which are faculties you need. You need to be able to tell a good idea from a bad idea. Discrimination is the most powerful tool. To have the intellectual discrimination to be able to say: “This idea doesn’t work because of this, this and this, this idea could work if we did this, this and this”. That’s really very useful. Don’t leave home without your sword – your intellect.

The wand is the will. This is the drive – whatever that is – in each individual. It is something above intellect, it’s above emotion, it is the soul, the will, the highest self, the thing that drives high art. High art is nothing to do with the lower personality. It’s not to do with fight and flight, fighting and fucking, eating, surviving – it’s got something higher behind it. That’s what wands are.

If you have all three of these things but don’t have the cup, which is compassion, then no. Yeah, you’ll be incredibly clever, you’ll be incredibly motivated and you’ll be incredibly materially solid, but without the compassion that the cup represents, you’ll also be a monster.

So you’ll need all four of these things, and that is true whether you’re a human being, a magician or a writer. You need to have these things balanced. Well, for me, I like to think that the people reading my stories are going to find them satisfying upon a material level, they’re going to work as stories about real people in a real world. That is the plot, I suppose. Does the story work on a material level – could these things actually happen in a material universe? So yeah, attending to material things, or the world of coins, or whatever, that’s the plot level, if you like.

The level of swords, of intellect, what I wanna know is, OK, if the plot works that’s not enough. I mean, anybody can think of a plot. A story. But to make it really work as a story, its gotta have, obviously, does it work intellectually? Is this stuff interesting to a reasonably developed intellect? And yeah, that’s important. Not just: “Does it satisfy the plot demands of the lowest level of audience comprehension”, but is it going to tickle their intellect, is it gonna give them new thoughts? If it’s just clever then… ah shit, you could end up like Will Self, or next thing you know you’ll be doing restaurant reviews, smoking smack in the toilet of John Major’s plane…

I dunno, this is my personal choice again, but I find some authors like Martin Amis or like Will Self, I find them overly impressed by their own cleverness, and I sometimes find it a very brittle sort of cleverness that doesn’t actually have a great deal of heart behind it.

It’s important to satisfy your readers emotionally – that doesn’t mean that you have to pile of the violins, tug the heartstrings, have Little Nell dying on every page, that’s not the way to do it, that’s manipulative and mawkish – that’s reactive emotion, its not a true feeling.

I mean, as human beings we tend to have feelings that come from inside ourselves, and then there are reactive emotions – someone says: “Boo!”, we get scared, somebody says: “I love you”, we say: “Aaahh”. These are reactions. They might have nothing to do with our true feelings. Someone says: “Grrrr”, we get angry. You know. Pfah!

So you need to connect with whatever your real feelings about things are. If you say you love your girlfriend, if you say you love your kids, what the fuck do you mean, exactly? What do you mean by that word, if you bandy it around? And that’ll take some thinking about, that’ll last for about ten or fifteen years. But these are things which are universal, they need to be explored. You know, Edmund Hilary: “Because it’s there”.

These are the big issues of human existence. And you need to have all these elements of your personality balanced, and you also need to have all of these elements apparent in your writing, if you want it to come across as a balanced thing, you need it to make plot sense on a material level, you need it to be an interesting intellectual structure with interesting intellectual ideas to satisfy people’s intellect, you need it to have emotional resonance and depth to give it humanity and warmth, and a kind of a beating heart, rather than to be a cold piece of artifice. Which I suppose, that’s probably down to characterisation, you want to put characterisation at that particular point in this writing Kabbalah. The emotional level – that’s probably down to the characterisation.

And, it needs to be about something. There needs to be some theme. Theme – that would be the solar centre, that would be the soul – you know, the book’s gotta have a heart. That is its emotional content, whether it does resonate, emotionally, so it’s gotta have a soul. The soul is the theme, it’s what it’s about. Is it about something that’s big, or important enough?

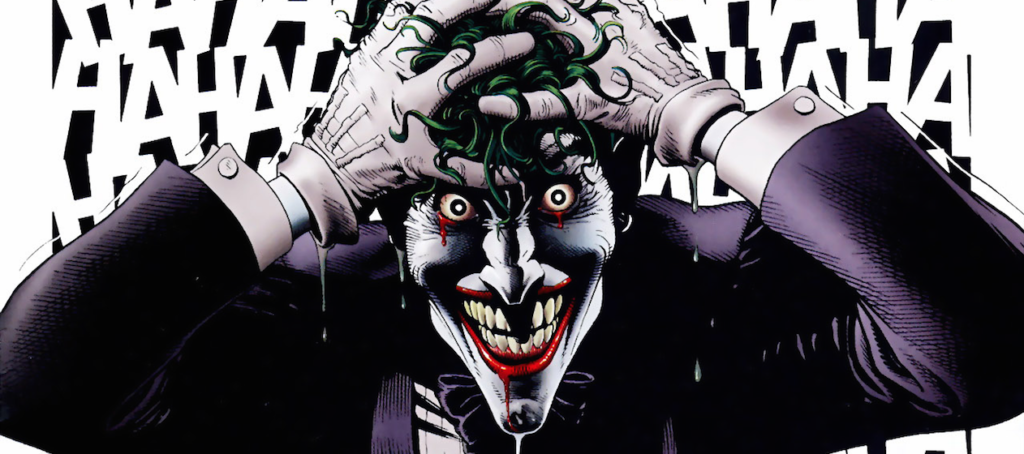

Art by Brian Bolland from The Killing Joke

Amongst my own work, The Killing Joke where Batman versus The Joker. Yeah, there’s loads of emotion layered on there. It’s quite clever. The plot works, on a material level. But it’s not about anything, it’s not about anything of human importance, it’s about Batman and The Joker and you’re never gonna meet anybody like Batman and The Joker. It’s of no use to you as a human being. It’s one of the works – there’s some very good things about it, but it’s lacking something, and it’s lacking soul. It’s not got the thematic drive that say Watchmen has, which I was doing at the same time. That was my big mistake. I was doing Dark Knight – I was doing The Killing Joke at the same time as I was doing Watchmen.

The approach that I was bringing to bear upon Watchmen – which had a much more important and universal human theme running through it – I brought back to bear upon a Batman-Joker story, and there was nothing there to support that kind of weight. So yes, purpose, theme, something that the whole work – whether it’s a short, 5-page story or whether it’s a 500-page epic: something that this is about.

Daniel: So what was Watchmen about?

Alan: A number of things. It started off as a silly-ass superhero story. We wanted to do a superhero story where we saw what would happen if you’d got a group of superheroes existing in a credible, real world, and what if these were credible, real characters emotionally-speaking, or at least as credible as we can make them. I suppose that was the basic premise – we thought we might get a darker than usual, grittier than usual superhero story out of it.

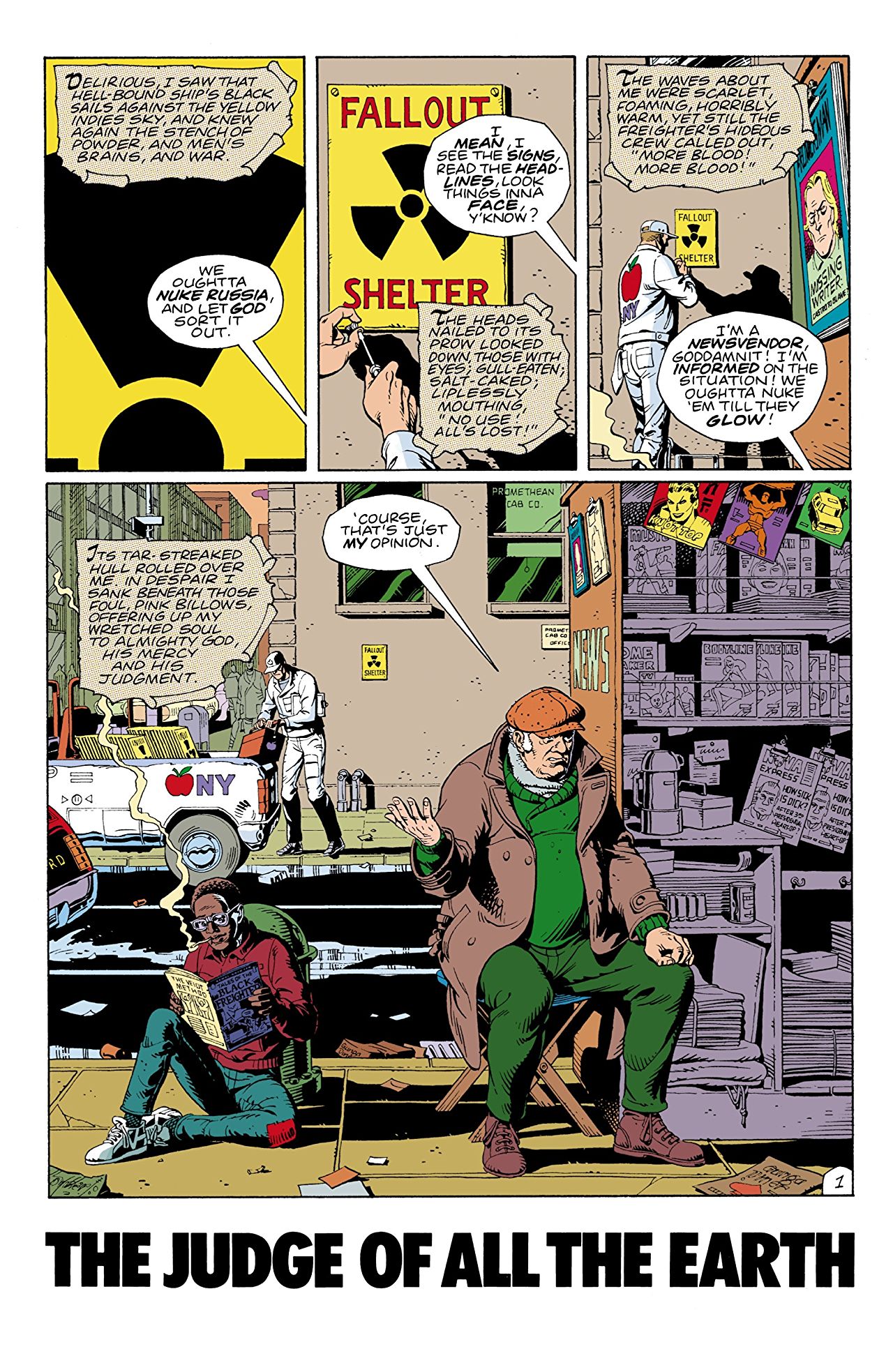

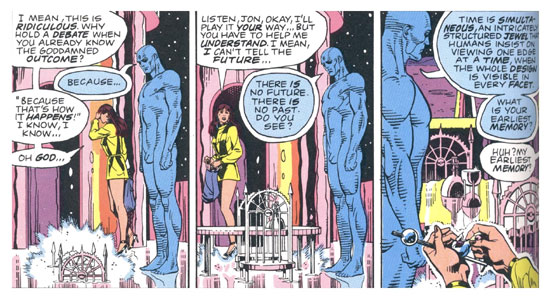

Watchmen #3 Page 1. Art by Dave Gibbons

We had got to round about the third issue when all of a sudden we started to realise that there was something growing out of the storytelling that we hadn’t really anticipated. There was something happening within the structure of the story – slightly interesting sparks, coming to life – I remember the actual page very clearly, it was the first page of the third issue? Where as the opening scene I wanted a bit of vox pop – you know, what’s going on with the man on the street, so we’d got a scene with the news vendor sitting there at his little shack, there’s a little boy sitting against the electric hydrant, reading a comic, across the street there’s people putting up a fallout shelter notice.

I thought: “People putting up fallout shelter notices, that’s kind of ominous, that sets a tone”. We started off with a close-up, I decided to pull back from a tight close-up of the radiation symbol on the fallout shelter sign. In the first drawing I did of the close-up of black and yellow, I thought: “Actually, that kind of looks a little bit like a very stylised picture of a black ship, so maybe, if I wrote a caption from the pirate comic that the little boy is reading, that would reinforce the reader’s identification with this black and yellow shape, as being a black ship seen against a yellow sky… and then I’ll also have some balloon from the off-panel news-vendor that will have some resonance with the content of this pirate caption, which is mainly about war. Piracy. Death”.

So I had the news vendor making a comment about the possibility of a forthcoming nuclear war, and as we continued to pull back, we continued with the imagery – the pirate captions, the dialogue of the news vendor – all of these things are starting to strike sparks off of each other, we noticed. And yes, Watchmen came to be about power. About power and about the idea of the superman manifest within society. Dr. Manhattan is pretty openly – I mean his name is related to the Manhattan Project, he’s pretty obviously a walking bomb. There’s more to him than that, but he is one level of human power.

The other characters who are all dealing with this world in their own different ways – the way that Watchmen fitted together, it was about power, but it’s about a lot of things. What I eventually came to the conclusion of about Watchmen was that the most important thing in it, was its structure. And I think, at the end, that Watchmen’s structure was what it was about. It was about its own structure. It was about a certain way of viewing reality. It was about a kind of perception which I think was perhaps not as prominent in 1985 as it is now, and as I think it will be in the near future. It’s not a linear perception of things that we do increasingly have in the 21 st century.

Details from Watchmen. Art by Dave Gibbons

Daniel: There’s a quote from Dr. Manhattan that seems to capture that perfectly: “Time is a multi-faceted construct that human beings insist on viewing one surface at a time”.

Alan: Yeah, that’s it… I mean, when Isaac Newton came up with the theory of gravity, nobody understood it. Nobody understood the theory of gravity. Then, given enough time, quite a few people did, and now, pretty much everybody understands the theory of gravity. Einstein, when he came out with his theory of relativity, there were probably five people in the world who had the first idea what he was talking about.

Now, not everybody in the world understands Einstein, but there are thousands of people, hundreds of thousands of people probably, who’ve at least heard of the theory of relativity and have some vague idea of what it entails. What I’m saying is, it takes us a while to catch up with…

Daniel: …the guys at the front…

Alan: …yeah, the guys at the front, who are actually shaping our view of reality. At the moment, quantum physics suggests all sorts of interesting possibilities for looking at reality. We’re nowhere near catching up with that yet, however, we catch up quicker than we did in the past because things are generally speeding up. Our technology acts as a kind of engine that speeds up our perceptions. There’s probably been more breakthroughs probably in the last 18 months than there have been in the whole of world history. And it gets faster.

Details from Watchmen. Art by Dave Gibbons

But I think with Watchmen the way that we were structuring reality, it wasn’t from the perspective of one person, it wasn’t from an omniscient Godlike perspective, it was multiple viewpoints. All of the different characters in Watchmen have got a completely different view of the world. Dr. Manhattan has this kind of dispassionate quantum view, Rorschach has got this fierce, morally-driven kind of psychotic view that is… something you could imagine people believing. Certain people. I might even believe some of those things myself on a particularly bad morning. The Comedian has got a particular view of the world, Nite-Owl – he’s got a largely romantic view of the world. All of these – none of them are presented as being more true than the others. We’re not sort of saying: “And yes, Dr. Manhattan’s view of the world is the right one”. Or yes, Ozymandias’ view of the world is the right one.

David Russell: What about Nils Bohr‘s ‘Greater and Lesser Truths’?

Alan: Yeah, he was a good one, Nils Bohr – The Copenhagen Interpretation.

[The first general attempt to understand the world of atoms as this is represented by quantum mechanics – Ed.]

Daniel: It’s a good play.

Alan: Is there a play of it?

Daniel: Copenhagen by Michael Frayn.

Alan: Ah right, I wasn’t aware of that, I was just talking about the actual Copenhagen interpretation of Nils Bohr when he first made it. I didn’t know they’d made a play of it.

Daniel: The play uses the metaphor – the structure of the uncertainty principle – in terms of the impossibility of knowing about a conversation between Nils Bohr and a German colleague of his – about interpreting history…

Alan: Well, if I interpreted the Copenhagen Interpretation correctly I think that at root it seemed to say that all of our observations – be they of remote astronomical events or of the hidden quanta – can only be, in the end result, observations of our own thought processes. I think I said in Voice of the Fire that he came up with that in the Copenhagen brewery – the Carlsberg brewery in Copenhagen, where I presume they had parties and things – well, it’s a haunting notion that, and hard to write off as the product of a special brew too many.

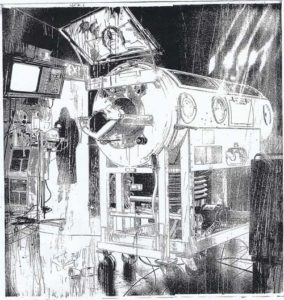

Art for the unpublished Big Numbers 3 by Bill Sienkiewicz. Script by Alan Moore

But these are viewpoints that we’re going to have to take on board. The same thing’s true of fractal maths. When I did the abortive Big Numbers I could think of new possibilities for viewing human society – human groupings – a healthier way. I could see possibilities in fractal maths – a new way of looking at how humans interact. And these are things I think it is important – vital – that we try and assimilate, these new options that we’re provided with, new ways to live, new ways to think.

We obviously have, as a species, a number of problems at this current time. The only way I can see for us to get round them is thinking our way round them – I can’t see us spending our way round them, we’re not going to be able to bomb our way around them. I could be wrong, maybe we can spend and bomb our way around them, but I would say on balance that if we’re gonna get round them at all, we’re gonna have to think our way around them, and that is gonna need new forms of thinking. I don’t know what they are, but I’d just say let’s try some of the options, and see if anything interesting comes up.

So, Watchmen started off as a grim superhero story, and ended up as a multi-layered metaphor for the effects of power upon society. But at the end of the day I think what Watchmen was about was its own structure, it was about the way in which Watchmen viewed reality, it was suggesting new ways in which to view reality.

The Dr. Manhattan sequence where he views time as a kind of solid with past and future present in any moment – that was very interesting to write, that was very liberating to write. You’ve got I myself having to adopt that viewpoint, and realising what a lot of poetry it brought to normal human existence.

One of the benefits of fiction, especially of fantasy fiction, is that is does enable us to put on these extravagant clothes. It enables us to do thought experiments. It enables us to imagine ourselves to extremes and to perhaps understand ourselves a little better by running through: “What is this? What would I think if this happened? What would I do if this happened?”. Running through these little scenarios, I think that can be useful. It might even be the point of art full stop. I mean, it’s gotta be for something, right?

Daniel: When you were talking about Dr. Manhattan viewing time as a solid object, the reader sees it that way too, and maybe as you say it is a way of letting us see something that we couldn’t see with our eyes by looking out the window…

Alan: Like I say, maybe when we’ve caught up with quantum theory, maybe when we’ve caught up with Stephen Hawking, maybe when we’ve caught up with some of the shit I read about in New Scientist every week, when we’ve assimilated that to the extent that we understand apples falling from trees, who’s to say that our perception of time wouldn’t change? I mean, if I understand Stephen Hawking, unless I’ve misread A Brief History of Time (laughter), the whole of space time, if it came into existence in the Big Bang, that was the whole of time, not just the whole of space that came into being and it all came into being inextricably linked together, then that means space time is a kind of giant football – more like a rugby ball, Big Bang at one end, Big Crunch at the other – and all the moments in-between are all co-existing in this one big hyper moment of space-time.

Now, I can accept that, intellectually, but to really know it, in the same way as apples fall from trees, to have it as an observable reality…sometimes I can almost get there. I’ve got a pretty good memory, and I’ve had odd premonitions from time to time the same way everybody does, never about anything significant, enough to strike a little eerie chord, and I came to think that time was happening all at once, and it’s only our conscious perceptions that arrange it all into a linear sequence.

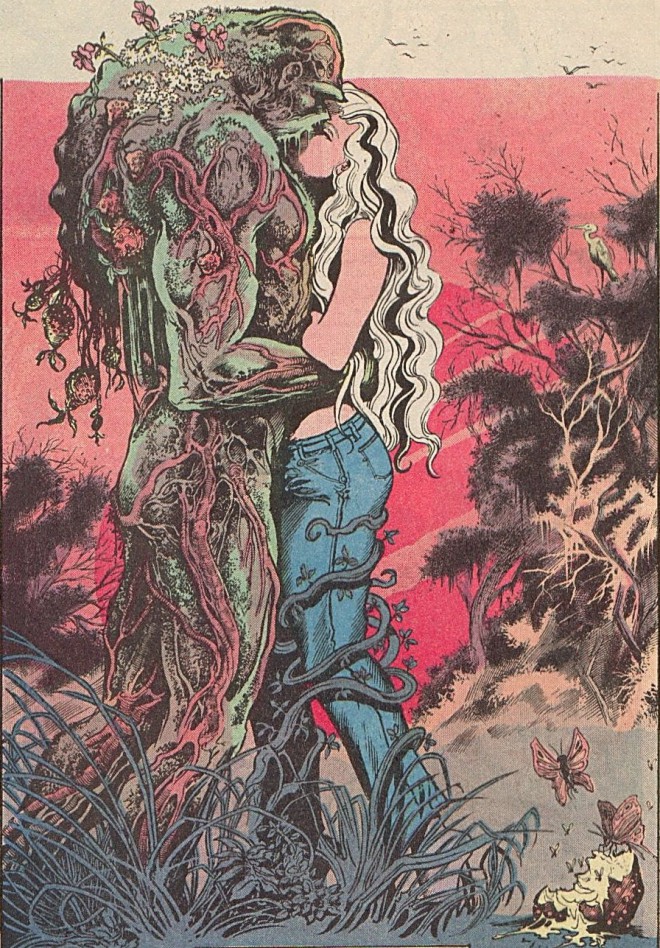

Art from Swamp Thing #34 “Rite of Spring”, written by Alan Moore, art by Stephen Bissette and John Totleben © DC Comics

And there by exploring the consciousness of the fictional Dr. Manhattan I can suggest to the reader what such a consciousness might be like. And Swamp Thing, where I was actually trying to think my way into: “What would a mass vegetable consciousness be like? What would the concerns of a vegetable consciousness be? What would its emotional range be?”. All these things are useful – or potentially useful – tools for getting people to understand natural phenomena from the inside, in the way that no other tool short of fantasy really can allow people to be put into those spaces and those mindsets.

Daniel: Going back to what you were saying about the underlying theme of Watchmen being its own structure, the name suggests that now I come to think of it: “Watch-men”, men of clockwork, men of structure…

Alan: Also, there are actual bits in it which are actually referring to ways of reading Watchmen , I mean, Dr. Manhattan’s perceptions, they are a key to the actual structure of Watchmen . In Watchmen … I mean just like that football structure of space-time, a book has the future of its characters, when it’s closed, a few small inches away from the present of its characters – all the moments within that story are contained within the two covers, so we tried to make Watchmen structured so that images recur all the way through, linking the present with the past and the future, giving foreshadowings of things that have yet to come, giving echoes of things that have already happened.

So, yeah, Dr. Manhattan’s perceptions are one key to reading Watchmen . Adrian Veidt with his multiple television screens, which is another key to reading Watchmen. Adrian Veidt is watching six channels at once and so, at various points in Watchmen, are the readers. It’s multi-channel viewing. You’re watching a pirate story, you’re watching a conversation on a street corner, you’re listening to symbolic dialogue, you’re seeing little symbols moving around. Both of those are ways of reading Watchmen that are encoded within the text of Watchmen itself.

Daniel: You started off by counter pointing that with The Killing Joke which you thought maybe didn’t work as well…

Alan: ‘Cos Watchmen has got a theme, a soul, a central reason for being. The Killing Joke was a Batman story. With the best will in the world, we’d designed the characters in Watchmen to kind of – or at least the way they developed – they were capable of carrying the weight of the narrative. They were interesting characters in their own right, people wanted to find out what was going to happen to Rorschach or to Dan and Laurie or whatever so it didn’t become oppressive, the structure, the mechanics of the storytelling, the clockwork…the ticking of the clockwork didn’t drown out the story. Whereas Batman and The Joker, they were designed in the late 1930’s, early 1940’s…

Daniel: But what was it that you thought you were getting right with The Killing Joke that looking back, you weren’t? How do you differentiate those two experiences? What was it you think you did wrong with that story?

Alan: Like I said a few moments ago, the problem with The Killing Joke was that I was writing it at the same time as I was writing Watchmen and there was leakage between one narrative and another. I was bringing to bear the mindset of Watchmen upon characters and situations that were too slight to bear them.

What I should have done, if I hadn’t been so immersed in writing Watchmen – well what I probably should have done is passed on writing Batman until I’d finished writing Watchmen – what I probably should have done is to have thought longer about the Batman story and tried to come up with a story that – just because The Killing Joke doesn’t work doesn’t mean that Batman’s a bad character, I’m sure there are perfectly good stories you could tell about Batman. The Killing Joke just wasn’t one of them.

What I should have done is to have thought more deeply about Batman as a character, what could be said honestly and effectively using that character, and then proceeded from there. But, on the other hand, a useful mistake. Because it irked me, I felt bad about The Killing Joke for a while. Not very satisfied with it.

And so I had to sit down and think: “Why? Why does this book not satisfy me?” Brian’s art’s lovely, you know it’s better than most of the post-modern Batman books…”

Daniel: Arkham Asylum…

Alan: Well, I wasn’t gonna mention any names… but yeah, I didn’t really like Arkham Asylum .

Daniel: That’s interesting, because that didn’t seem to work as much as anything I’ve read… and I’m not sure why.

Alan: Not to slag anyone off, but at the time, I met Dave McKean after Arkham Asylum came out, always a difficult time, the book’s come out, by someone you know and get on with, and you don’t happen to like it, then, you have to choose between honesty and diplomacy, and I remember saying to Dave that I hadn’t liked Arkham Asylum , I thought his art had been beautiful, lovely, but it was the story that the art was in service to…

Daniel: Perhaps it wasn’t really a story…

Alan: Well, it wasn’t much of a story, the story didn’t really resonate for me on any level, and the fact that it had got Dave’s beautiful sumptuous artwork appended to it, I said to Dave that it was like putting an exquisite golden frame – and I said your art is an exquisite golden frame, it is, it’s exquisite – it’s like putting that exquisite golden frame around a dog turd. I said it’s not gonna make the dog turd look any better. In fact the dog turd can make the exquisite golden frame look a bit – an attempt to polish a turd.

It’s like, the artwork, if it’s not in service to something which has depth, it can be the most gorgeous stuff in the world, and the more gorgeous it is, the sillier it will look. Because you’ll be thinking: “Someone expended all this effort and created all this beauty on this story”. It’s like the gap between the story and the art is vast.

Daniel: That brings me to something I’d like to ask, which is, it’s a collaborative medium, unless you’re a writer-artist. How do you see the relationship between writer and artist? I mean, some writer-artists have stated that they see no place for a writer who isn’t also an artist in the medium – for example, Dan Jurgens…

Alan: I don’t think I know who he is… he wrote The Death of Superman ? Yeah, yeah (smiles) … a valid opinion…

Daniel: But that’s not what I want to talk about at any length…

Alan:… Got plenty of artists that can’t write… not mentioning Dan Jurgens in any way, of course…

Daniel: Bit more of an auteur really…

Alan: An auteur. Yes, I think he probably is…

Daniel: How you do you see the relationship of writing for an artist, which is not the most common writing experience?

Alan: It’s a good question, and I’d say that of all my talents, working in the comics industry, my talent for collaboration is my most prized and probably my most highly-defined and adapted-

Daniel: That’s interesting, because many people would see you as a writer rather than –

Alan: One of the things that I learned very early on was – I’m very perceptive when it comes to comics artists – I pride myself on – I can look at an artist’s work, and not only see why it’s good, I can also see things that that artist could do that not even the artist knows that they could do – I can see possibilities, you know, a quality in someone’s art, if you could bring it out, marry it to the right story, let them run riot with this particular thing that they do.

So what I do, when I, writing a story – OK, back when I used to write for 2000AD and I didn’t know who would be drawing it a lot of the time, then you have to write an artist-proof script. You put in all the details you can think of and you try and make it as entertaining and as exciting for the artist as possible, so that even if they’re not inspired at all, maybe once they’ve read your story they’ll want to give it just that extra little bit of effort.

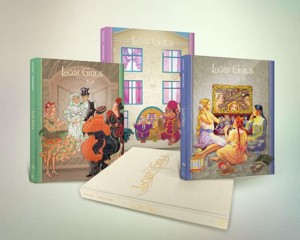

Lost Girls by Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie

Now if you’re writing for an artist where you do know who they are, it all becomes a lot easier. You think in terms of pleasing the artist first. It’s like – I could give examples from any of the works I’ve done – errr – Lost Girls. With that, me and Melinda Gebbie, we both knew that we wanted to do an erotic piece of serious fiction.

When we were casting around for how to do it I mean I was looking at Melinda’s work, it was the first time that I’d seen her colour work, and I suddenly thought: “This colour work, this soft crayon work, it’s beautiful, it looks like children’s illustrations so therefore it looks fake”. Her erotic work is really wild. If you were to do the erotic stuff in this beautiful textured and layered coloured crayon, that would be really subversive, you could get away with anything, no matter how grotesque or disgusting it might sound, that enough layered coloured crayon, prismatic coloured crayon, and it’s gonna look like an illustration from The Butterfly Ball or something like that, it’s gonna look like a children’s favourite.

So, also by that time I’d realised that Melinda was quite good at, and seemed to enjoy, pastiching other artists’ styles – she could do a pretty good Egon Schiele, a pretty good Aubrey Beardsley, a pretty good Klaus Mucher, so all right, maybe I could work that into the book in some way, something that would give her the opportunity to do those things I know that she’d like. These things have all shaped, the content and the storytelling of Lost Girls.

With Promethea, J.H. Williams told me, early on, he really likes symmetry in a spread layout, he really likes working with spreads. So, the unit for most of my comics is the page, the unit for Promethea is the spread, I compose each in two-page bursts, and work out: “Is there anything interesting visually we can do with this spread?”

So, in all instances… it’s a bit like circus horses. The reason the circus horses dancing to the music works so well is that that’s not what’s really going on. The band are playing along with the horses. The band are playing along with the random capering of the horses, and it appears like a beautifully synchronised piece of dance. That’s something like what happens when I’m working with an artist. I am looking at this capricious, prancing, wonderful style, whether that’s Oscar Zarate‘s or Kevin O’Neill‘s or whatever, and I’m thinking: “What sort of music can I put to this capering, this dancing, that’ll make sense of it and will bring out its best qualities?”

Because if the artist is enjoying it they’re going to pour all their energy and enthusiasm into it, which is gonna give the work a life you could never have achieved on your own. So yeah, collaboration is vital and it’s done by understanding the person you’re working with. So, develop your perceptions and sublimate your work to the artist. It’s like dancing or sex or – both of those are decent metaphors. You don’t lead when your partner’s leading. You sort of have to kind of get into a rhythm, pull back, let the other person do the solo, then maybe they pull back and let you do a bit of a solo…when you get into the right sort of tempo then a good story will generally be the result.

Daniel: One of the very crude distinctions between different schools of comics scriptwriting is to label one the plot-driven approach –

Alan: The Marvel school.

Daniel: Do you think it’s accurate – and if so what it says about writing and about the medium? That the more you do write full-script and the more closely you design the comic from a writing/ ideas/ concepts point of view, the less visible the collaboration is – the more seamless the collaboration is – between writer and artist, but also the more there is of the reader fully immersing themselves in the story, and not being aware of “Oh, I’m reading a comic”, not having a huge explanatory text box saying: “Meanwhile, on the other side of town…”

Alan: Exactly. I’d say that one of the greatest compliments I’ve ever had for my work was when Terry Hillier, reading the first few episodes of From Hell, commented to Eddie Campbell that: “It reads like the work of one person”. Perfect. That’s what I’m aiming for with everybody. I want it to read so naturally that it will be just the work of one person.

But, the Marvel-style approach, this started with Smilin’ Stan Lee, Stan ‘The man’ Lee, and I’ve gotta say, and this is only my opinion having seen Jack Kirby’s pencils, I think that the process went something like this:

Galactus, art by Jack Kirby © Marvel

Stan Lee comes up with an idea: “Right, next issue of The Fantastic Four , like, what if there’s some really big powerful threat from space, sort of – or according to some people, what if in the next issue, the FF – the Fantastic Four – fight God”. And Jack Kirby goes away, and he thinks: “Galactus… Galactus eats planets…and he’s got this herald… and it’s this silver guy on a surfboard and he goes before him…and this guy’s so frightening that solar systems will switch off their suns so that he doesn’t notice them, they’ll black out their entire galaxies so that he’ll pass them by, and yeah, The Watcher, he intervenes and fills the Earth’s sky with illusions to keep this creature away, but it doesn’t work…”.

And you’ve got Kirby, he’d pencil five pages a day… he just wasn’t human. He’d just sit there pencilling five pages a day, six pages a day, nine pages a day, and in every panel – so he’d be breaking it down into stories, he’d be breaking it down into a continuity of images, he’d be inventing the characters, he’d be writing the dialogue suggestions – very crude, very quick, but sometimes quite detailed.

Then this would go to Stan Lee, who would look at the story that Jack Kirby had written, would dialogue it in his own unique way – he would put in a lot of ‘thees’, ‘thous’, ‘face front true believers’, footnotes, and then it would go out as ‘Fantastic Four created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’, but it was only one of them who had a share of the action on the characters, and that was… the smiling one. And that’s probably why he was smiling, come to think about it.

And the Marvel method – I’ve heard people – Archie Goodwin, who was a lovely man, a great comic writer and somebody I respected a great deal – I once said to him: “I can’t see any advantage in the Marvel method”. And he said: “Well, sometimes it allows for serendipity”. That may be true. But I would say that it would be so infrequent – and I mean looking at the vast output of Marvel comics during the last thirty years of the twentieth century – those moments of serendipity were pretty few and far between.

I’d say that the disadvantages of the method outweigh whatever slender advantages there might be. It’s lazy. I’ve gotta say, it’s lazy. And it leads to homogenous product because think about it – I mean, if the artist has no real idea what anyone’s gonna be saying in a particular panel, then how can he put a particular emotion on their faces while they’re saying it? So you have to go for this kind of – the emotional range of Marvel characters is generally ‘mouth open – mouth closed’. Whereas with me, if I spec a page –

1963 – Tales of the Uncanny

Daniel: Maybe that’s why they wear masks…

Alan: Well, that could be it. It’s not helped by the fact that all the main Marvel characters all look like the same person with different hair colours. So do the female characters. It’s a process of homogenisation, so it should be resisted.

To me – I mean, I have worked close to Marvel style, when we were doing the 1963 pastiches. But even then it wouldn’t be me saying to Rick Veitch or Steve Bissette: “Yeah, and he fights a cockroach kind of guy in this issue, now go away and draw me the story”. (laughter). I was doing exactly the same things as I always do – I was breaking it down into tiny little pictures – the only difference was that I was phoning through the descriptions to Rick and Steve over the phone: “Yeah, all right, first page, five panels, in the first panel this happens and this happens, do you understand?”, and Rick would say: “Yeah yeah, I’ve got that, that looks great”.

“Right, second panel overhead shot, we’re looking down”. Then they’d draw the pencils, send them to me and I’d dialogue them, and I’d have a vague idea of the type of dialogue that would be appropriate even when I was drawing the pictures, so it was a more streamlined – it was closer to the Marvel method but actually it was just a more streamlined version of my normal method.

So yeah, I really think that if a comic’s gonna have a writer then the writer should write. I think that most of the writers I admire in comics, they put the work in. Neil Gaiman, his scripts are about halfway between mine and – in terms of length and detail – he’s about halfway between me and average comics scriptwriters. For average comics scriptwriters a page of comics is probably gonna be a page of manuscript, whereas for me it’s at the very minimum a page of comics is two pages of manuscript, sometimes three. On one of those Promethea issues, two pages of comic took me three pages to write for Jim Williams…but I think it’s worth it, and I think that the results show.

There’s things I’ve done in comics that would not have been possible – I mean that Promethea #12, tying in Tarot cards and all the rest of it, there’s no way that could have been done other than with a very detailed full script.

Daniel: What does that say about comics – it’s almost paradoxical – that they’re most successful in their own terms when the person who the average man in the street would think was in the driving seat – the artist – is in fact written for to a larger extent?

Alan: Well, I think it says that comics are – I mean, alright, some of the best creators in comics have been writer-artists. The majority of comics artists – some of the best ones, Harvey Kurtzman, artist-writer, Will Eisner, artist-writer, Frank Miller – well, Dark Knight one was good, not so sure about Dark Knight two, but yeah when Frank was cooking, he was a good artist-writer. Art Spiegelman, who I believe has been very vocal about – at least in the past – how the mainstream industry, mainstream comics could produce nothing of worth, because it was not the work of one individual, it was a conveyor-belt process, and thus soulless. I’ve got a great deal of respect for Art Spiegelman as an intellect, but I think he’s wrong on that one.

I mean, it depends how you use the collaboration process, I’m sure it can be soulless, I’m sure it can be a conveyor belt, but conveyor belt does not begin to describe the collaboration between me, Dave Gibbons and John Higgins on Watchmen , it doesn’t really describe the collaboration between me, J.H. Williams, Mick Gray, Jeremy Higgins and Todd Klein on Promethea. These are – everybody’s putting in ideas, and I’m working trying to think of new colouring effects for Jeremy to try out, I’m trying to think of what to do with the lettering this issue, anything new that I can come up with to bedevil Todd this issue, make him work for his money.

There’s nothing soulless about the way that I approach collaboration – the exact opposite, I try to involve everybody so we’ve got everybody’s energies pouring wholeheartedly into the book, because it is what they most want to do. And then you’ve got all of those energies in one harness, harnessed to one project, and you can take the story to lengths you would not have imagined possible.

David Russell: So would you typically hook up with an artist before you begin work on a story?

Alan: Well, generally if possible. Sometimes I’ll have the idea for the story – like with From Hell I had the idea for the story and thought: “What artist would be perfect for this?” And I thought about it and I realised with From Hell you needed an artist who was able to take a very low-key approach to something, because I didn’t want it to be a horror story in the comic book sense, I wanted it to have a much more profound horror to it, and that needed somebody who could conjure up a much more believable, mundane everyday reality, and who’d got pretty subtle, low-key sensibilities. Eddie was perfect.

Detail from League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Vol 2, Issue 5, art by Kev O’Neill

League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, when I was musing about: “Who would be the perfect artist for this?”. Once the image of Kevin O’Neill‘s art came into my mind I knew that that would be exactly right. The kind of cartoonish, English caricature quality in Kevin’s work would really give a lot of bounce and energy to the script – it would dispel the heaviness of the Victorian setting, it would – just Kevin’s sense of design would bring such a lot to the script.

These were things where I came up with the idea first as opposed to Watchmen, where me and Dave sat down with the idea of doing something together and let it evolve from there, but with League of Extraordinary Gentlemen or From Hell, the idea was there first and then I kind of picked those artists, because they seemed – according to my instincts, my intuitions, to be the perfect ones for the job.

Collaborations all have a different nature, they all work in different ways, because any two individuals are gonna have a different chemistry between them. You have to be sensitive to the person that you’re working with and they have to be sensitive to you, to a certain degree. And you try to work as one organism, as best as possible, and it is possible.

Daniel: What are the pitfalls to collaboration?

Alan: Well, don’t get an attitude. Don’t suddenly decide that the way to make your mark upon the industry is to stamp your presence over every story indelibly. I mean, I’ve seen some terrible examples within the industry of an artist and writer at war –

Daniel: Was it Warren Ellis?

Alan: I was thinking more about some of the American books I’d seen, where you had an artist with a certain amount of fan popularity, you had a writer with a certain amount of fan popularity, and you can see instances where the writer had decided that the artist was getting too much attention and that he wasn’t getting enough, so the writer had covered as much of the artist’s work as possible with huge word balloons (laughter), and then the artist will start getting revenge… and it’s not a collaboration, it’s a war. I don’t know whether – I mean I speak to Warren, and he always seems a polite, well-mannered young man when I speak to him, maybe he’s trying to sound a bit –

Daniel: I think what he was talking about something quite specific where he’d written something and the artist hadn’t liked it and decided to draw something else…

Alan: I’ve never had that happen. Yeah, but the thing is is that I’ve seen some of Warren’s scripts. Warren’s scripts aren’t very long. I mean I’ve seen… Avatar Comics brought out something called Bad World that Warren had done… I mean if you look at Warren’s scripts, there’s not a lot of dialogue, they’re not dialogue-heavy, shall we say. In this Bad World thing they actually reprinted the scripts to all three issues in the back section of the third issue. These were the full scripts. It was one panel per page and there was a little caption – no, one panel per spread I think – with a terse little caption talking about it. And OK, if that’s how Warren likes to work, that’s fine, but if he does have trouble with artists suddenly deciding that they’re gonna be a bit creative with the last quarter of a comic or something… I mean, I’ve never had that problem. It might be that if you’re gonna be very very loose with your instructions to the artists, perhaps you’ve not got quite as much room to complain if they take that as you giving them a long reign.

I mean, I always in my scripts will give instructions saying: “Look, despite the fact that there’s all this previous detail, if you’ve got a better way of doing this panel, then as long as you basically understand the effect I was going for here and can think of a better way to achieve it, then please do, I’m counting on you, if you’ve got a better idea than me to throw it in, because that’ll make the story better”.

Not many people take me up on it, but some do. Jim Williams’ll change things because he’ll suddenly see that actually these five panels could be arranged more interestingly and still have the same story power, if he did it like this. And I try to give them complete leeway, so they’ve got as much support as they need if they haven’t really got an idea of how to do the page, but it’s not a burden. They’ve also got as much freedom as they want, which I think is the best way to work with people generally, let alone create with collaborators. Give people the support that they need and the freedom that they want. Then you won’t go far wrong.

It’ll probably mean more work for you, but the end result is that your collaborators will feel that they’re collaborating with you – if they feel you’ve done a good job for them, they’re gonna want to do a good job for you. It becomes a very benign competitiveness that you can get into sometimes with comics, where you’re trying to show off to each other.

When the artist has read your script, liked it and then done an art job that has gone beyond your script, then a kind of benign and lovely gauntlet’s been thrown down, and it’s a kind of impetus to make your next script really knock the artist out, and then they match that, and so on. It’s a good way of amping up the creative energy on a project.

Daniel: But you have to adequately specify what you require of your collaborator.

Alan: Be clear. You can’t be too clear. Whether in your actual script or your actual storytelling. If you’re gonna have ambiguity in there, make sure you know why you’re having ambiguity in there. Make sure you’re not just saying it has ambiguity because you haven’t actually figured out what it’s about. There are plenty of reasons for using ambiguity, but one of them is laziness. Make sure that you’re being as clear as you can be.

I can’t see any point in – some artists seem to produce something not very pleasant to read, and then they’ll say it was meant to be challenging. Now, I like the work that I read to challenge me, I like it to expand my horizons. But that is the equivalent to a challenging debate, which I’m sure most of us would welcome. But if the artist or writer is trying to challenge me in the manner of an obnoxious street drunk, then that’s a different sort of challenge and it’s not something I particularly picked up the book for. If I’d wanted that, I’d have hung out in the taxi rank downtown on a Friday night at chucking out time.

Why were you trying to challenge your audience? What have they ever done to you? I prefer seduction, hypnosis, I don’t want to scream at my audience and demand that they understand my gemlike pearls of wisdom. I once said that a good way to describe my approach to writing is that in the story, in the telling of it, the dialogue, the characters, I introduce myself to the reader, I talk to them interestingly, fascinatingly, calmingly, I get them to sort of follow me up the alleyways of the narrative until they are so far within it that they probably can’t find their way out, and then you can do whatever you want to them.

Some of the things that I put my readers through are pretty extreme – I mean the Mary Kelly sequence in From Hell , it was very gruelling to write, it was very gruelling to draw, and I know that it was very gruelling to read for some people. Some people had to put the book down, it’s an intense little scene. I couldn’t have got the readers to look at that without the preceding 400 pages, or whatever it was. I had to get them to trust me. And I don’t think I betrayed that trust. I had to get them to go with me into a horrible place –

Daniel: Well, it was a story about Jack the Ripper…

Alan: On the other hand, there are a lot of ways I could have done that scene and the lead-up to it that would have made it merely unpleasant. I mean, as it is, there is something terrible about it, which is good. If it had been merely unpleasant – a bloke cutting up a woman – than that would have let down the whole book and probably not done an awful lot for my reputation as a writer. I knew that if I was gonna have a scene that stark, that intense, then I needed to do an awful lot of groundwork, treading very carefully every step of the way until you finally throw open the doors and take the reader into that room, and say: “Right, this is the heart of the story”.

I think about the collaboration a lot, I also think about my relationship with the audience. These are the people I don’t know, the people I can only vaguely imagine. But art, writing, surely one thing that all of this is is an attempt to communicate something. So why would you choose to communicate that which you wish to communicate less clearly, less powerfully?

If you’ve got something to communicate, then you would want, I would think, to communicate it as clearly, as powerfully and as affectingly as possible. So in any communication there are two factors, there is the transmitter and the receiver. And you wanna make sure that the receiver receives the message that you were sending out with clarity, but at the same time you don’t want it to be…insultingly simple.

(We then returned to a discussion of ‘signal to noise’ in writing again, covering the same ground as was gone over previously, before moving on to fresh topics).

You could end up as a writer’s writer, and that would be a terrible fate. What that means is you’d be a writer where all the other writers would say: “God, I wish I was as brilliant as him, and I’m glad I’m not as penniless as him”. I’ve known a few borderline – Kathy Acker was nearly a writer’s writer, other writers would say: “Jesus, how does she do this stuff, these sentences are fucking fantastic…the way they sort of self-destruct…”. But she was not easy and she was not popular. Iain Sinclair, I think – yeah, let’s go out on a limb – the finest writer currently working in the English language – Downriver, one of his best books, took him five years to write and he got 2000 quid for it, how many it sold I don’t know, but probably not a lot.

Most writers, even the very best ones, especially the very best ones, don’t often make a living from it. You go into any branch of Waterstones and 90 per cent of those books on the shelves, unless you’re talking about Catherine Cookson, Stephen King, Jeffrey Archer – the ‘giants’ as I like to think of them – unless you’re talking about them you’re talking about someone who is a teacher, or a social worker, or works in a bookshop, or works as a lorry driver, you’re doing something to pay the rent and then working into the small hours while the wife and kids are asleep.

There’s levels, there’s levels to being a writer, and I think the thing to decide is the level you’re happiest at. If you’re happy writing pulp adventure stories then for God’s sake write pulp adventure stories, and if there comes a point when you’re no longer happy writing pulp adventure stories, try something else.

Don’t think that you have to write – just because literary critics decided some time in the 19th century that Jane Austen‘s comedy of manners was the only form of literature that could really be considered literature. Basically it’s because her novels were about the habits of the class that could afford to buy books. They were about the habits of the class of people who were criticising the books. They were flattering. It was holding a mirror up to a particular strata of society – which included the critics – and they said: “Yes, our ways, our vanities, our funny little intrigues, this is the stuff of legend, the only stuff of legend. For God’s sake, don’t write anything in genre. Don’t write detective stories, because they’re low and vulgar”. Even if you are Raymond Chandler, even if you are an extraordinarily beautiful and gifted writer. If you’re writing detective stories, forget it. Ghost and horror stories, well, we’ll just about allow Poe, but no, on second thoughts, and certainly don’t even consider people like Lovecraft, who couldn’t write . Who had a “clumsy prose style”. Apparently.

Clark Ashton Smith? Gaudy. Forget about him. Arthur Knacken. You’re not gonna find these people anywhere in Melvyn Smith’s list of 100 novels you simply must read. You’re not gonna find any genre. You’re mainly gonna find novels of manners. You’re not gonna find any science fiction, even if it’s H.G. Wells or Olaf Stapleton, because science fiction is a lower art form than the novel of manners.

The Michael Moorcock Library Volume 4 – The Weird of the White Wolf

I’d say to anyone aspiring to be a writer: write what you like. Write what you have genuine enthusiasm for. Don’t write to get a Booker prize. Angela Carter, God bless her, always used to refer to “that sort of person” as “shortlist victims”, and it’s true. Michael Moorcock is never going to get a Booker Prize, but he’s a better writer than 100% of writers who have won the Booker Prize over the last 20 years. But he’s vulgar, he used to write comics, he used to write science-fantasy trilogies. In three weekends. On speed. He used to write the Talisman adventure libraries, he used to write Sexton Blake, along with Jack Trevor Story, another writer who will never be included in the canon of great British writers. Jack Trevor Story, one of our very best writers ever.

David Russell: Maybe in a hundred years…

Alan: Nah, sadly not, he’ll have been completely forgotten… he’ll have been forgotten three times over by then. Yeah, the re-forgotten as Iain Sinclair calls them. People like Gerald Kersh, people like Jack Trevor Story, John Lodwick, people who are fine writers. Their books aren’t in print anymore, nobody’s concerned.

(Editor’s note – Valancourt Books now publish a number of works by Gerald Kersh)

I mean, Jack Trevor Story, I’m a big collector, I’ve got nearly all of them, which is difficult in this day and age. I’ve got all of the Horace Spurgeon Fenton trilogy, The Wind in the Snottygobble Tree. Marvellous. The Snottygobble Tree is the Yew tree, so called because of its sticky white poisonous berries. The Yew tree grows particularly well in graveyards, it thrives upon a human loam. So in a lot of cemeteries you get the Yew tree growing, or a ‘Snottygobble Tree’.

So the title, The Wind in the Snottygobble Tree, it’s funny, but it’s also kind of poignant… it’s talking about human life. Human life is just the wind in the Snotty Gobble Tree. The wind in the graveyard. He was very funny, Jack Trevor Story, very sad, poignant.

There was someone who, after he died, suggested the Jack Trevor Story prize for literature, where the prize would be something like £200 and the only condition would be – say £500 to £1000 – and the only condition would be that after two weeks the recipient would have nothing to show for it. Which was pretty much the pattern of Jack Trevor Story’s life. Whenever he got any payment, two weeks later he would have nothing to show for it.

In 2002, after this interview was frist published, Savoy Books published an edition of A Voyage to Arcturus introduced by Alan Moore. A limited number of copies are still available

But these are my heroes, these are the people I am particularly fond of, perversely fond of, people like David Lindsey, who wrote A Voyage to Arcturus, one of the most mystifying and brilliant British fantasy novels anywhere. Completely forgotten.

Less forgotten, but still ignored, William Hope Hodgson, who wrote House on the Borderland, The Night Land, various other books… a visionary genius. But forgotten.

There are all of these people, who because they were too cheerily vulgar, too proletarian, something like that, because they weren’t well behaved enough, in literary terms. Because they seemed possessed, or intoxicated, or vulgar or rude, they weren’t allowed in past the doormen, into the literary banquet going on. That was only for your Iris Murdochs, to your people who were on the list.

There were a lot of people who didn’t have the right kind of shoes on to get in. And those are the people I treasure the most, because they are the voices that are most in danger of being lost.

Daniel: I feel somewhat base bringing it back to comics yet again, but that might be an interesting point. At least within the English-language tradition, comics have been dominated by genre fiction, particularly the superhero genre which could be seen as even more ‘vulgar’ than the ones you mentioned before. Without denigrating those genres, do you think because of this, comics writers have to ‘smuggle in’ other themes?

Alan: The beauty of a genre is in transcending it. It’s like I was saying about putting limitations on yourself when we were talking right at the beginning.

Daniel: The blank page.

Alan: The blank page. The genre is the straightjacket and you can do some nice Houdini tricks if you put on a restrictive enough genre. And you don’t have to look very far to see some brilliant examples of that. The detective story genre in the hands of Mickey Spillane is dull – dire – not very interesting. But you get someone like Raymond Chandler who suddenly brings in this weary moral element, and genuine compassion and human insight, and he transcends the detective genre, and makes it something it wasn’t before.

Daniel: And it’s very hard to think of how that emotional range could have been expressed – better – in another…

Alan: Well absolutely, it’s difficult to see how it could have been expressed better in Pride and Prejudice , or a novel of manners, because he used the extremity of the detective situation – the isolation, the moral loneliness – as a counterpoint to this bleak image of a corrupt San Francisco he was painting. I think with my own work, with things like Watchmen , if they succeed it is because they transcend the superhero genre. They take it somewhere where it had not previously been. I’m not saying that every work I’ve ever done in superheroes has transcended the genre, but that is one of the main pleasures of genre.

It’s putting on a straitjacket and then making a big spectacular display of springing out of the straitjacket with no concealed lock picks or anything like that – underwater – with a hopeless genre. The more hopeless the genre the better, really, because people are gonna be more surprised if you do something good with it-

Daniel: Which puts comics writers in a privileged position in some ways…

Alan: Well, if they are up to that particular act of aesthetic ju-jitsu, if they can actually turn the weight of negative expectation that is being hurled against them, by some crafty kind of ju-jitsu move, if they can turn that round and make that weight work for them….so it depends very much upon the writer and how they are viewing the kind of creative milieu they are working in. But yeah, for me I’m always quick to try and find the advantages in any situation, which can often be the apparent disadvantages. There’s ways you can look at the disadvantages of a situation and see that they can be used as a kind of lever to spin the project in a completely different direction. If this is a problem, then how am I gonna get around that problem?

Pornography. Obviously, there’s a problem in how are you gonna do pornography that people are gonna respect and people are gonna like? I’ve read most of the feminist critiques of pornography, some of them I can dismiss fairly easily – Andrea Dworkin – some of them less easily. Some of them I don’t wanna dismiss. I think they’re perfectly valid. So, how do you produce a piece of red-hot pornography that answers these critiques? That avoids the pitfalls like that? These are all big problems, but the work you get out at the end can be all the better for the kinds of travails you’ve had to go through to get there.

So, have you got a last question, or anything like that?

Daniel: It’s never good to end a conversation on a negative note, but if there’s anything more you could recall that’s a classic mistake, something you learned not to do early on, because you’ve spoken a lot about the positives…

Alan: OK, a negative… a negative…what shouldn’t you do…you shouldn’t… you shouldn’t come up with things that you shouldn’t do. I’d say what you should do is probably make all the f******* mistakes that you are capable of. Don’t make too many mistakes where it matters, but don’t be afraid to try anything. Don’t be afraid of failure, don’t be afraid of trying.

And if you do fail, nobody likes to fail so you probably won’t either, but if you do fail that’ll probably just give you the incentive – not to not try that thing again, but you’ll have some idea of how next time, you could perhaps do it, and succeed.

Some of my stories have been failures. In the American Gothic run on Swamp Thing, where I was trying to tie stock horror icons in with horrific aspects of contemporary society. I’d got the treatment of women tied in with the werewolf story, and I tried to do a story that tied in zombie imagery with a comment on racism – and it didn’t really work. A valiant attempt, some lovely bits of writing in it, but I should have thought it through more, I ended up not quite saying what I’d wanted to say, it was muddy, ambiguous – a failure. And like I say, I don’t like failure, so I had to try and analyse what I’d done wrong and work out ways that I could avoid making it again.

So, don’t be afraid of failing – once or twice – because that can be a big learning experience. If you don’t fail once or twice, you’re probably not reaching far enough, you’re not taking enough risks. You should also remember – here’s some other bits of good advice: if you notice something that you do, that probably means that you do it too much. Stop it. Do something else. If you notice something that is becoming a staple part of your style, abandon it, otherwise it will become a rut, and it’ll be a crutch that you lean on, an easy little thing, and all of your books will be exactly like the last one. I’m sure we could all think of a lot of authors – perhaps quite popular ones – who write the same book over and over again – sometimes very entertainingly – but they’re not moving anywhere. I’d say keep moving – if you stay still, you die. As a writer. You might die very lucratively, but creatively you’re not gonna be cutting it.

Also, if you’re sure you can do something, that’s probably because you’ve done it before. If you’re sure you can do something there’s probably no need, no point in bothering to do it. This is perhaps not advice for people when they’re starting out. When you start out, you want the security of knowing you can accomplish these things. But if you get on, there’ll come a point when you realise if you’re sure you can do something, then there’s no point in doing it because it’s too safe. Best thing is trying to find a decent-looking cliff edge and throwing yourself over it. Think: “What would be really impossible to do – or nearly impossible to do? What am I not sure I could do?”.

(We again returned to a conversation about Voice of the Fire, covering some familiar topics before moving on to conclude with an observation about coming to trust the process of writing itself).

… so it was leaving an insane amount of stuff to chance. I knew in that last chapter I knew I had to have turning up within my field of vision within Northampton spectral black dogs, I had to have a severed head, a real, human, severed head turning up somewhere in Northampton, because these were motifs running through the entire narrative. Since all the other stories had taken place in November, this was right that I had to write about things that happened to me during the November when I was writing this last chapter. And I think on the last night of November I’d taken a bunch of mushrooms, I’d done a ritual, I was basically asking the gods: “For fuck’s sake, help me find a way out of this novel, before I go mad. Give me an ending”.

And that was the night I came downstairs and saw the details of this murder case on the telly that had been held at the County Court, behind Sceptre Church at Campbell Square there, and it was the details of a murder trial that had happened previously but had just come to trial in November. In Corby, an old man had had a home invasion, someone had broken into his house and he’d been murdered. The detail that hadn’t come to light at the time was that his head wasn’t there, at the crime scene. It was found, later, by a black dog, under a hedge, which… perfect.

I mean, I’m sorry for the guy and all that but I mean I’d got stuff in the 11th century chapter about how the head of St Edmund was found being guarded by a big black dog, so to have this conjunction of black dogs and heads – and it was the first decapitation I could remember happening in Northampton during my lifetime. They’re not that common, so the fact that it should happen right when I needed it to happen to finish my novel… yeah, you’ve gotta trust – when you get to a certain point, the best advice I can give to any writer is: trust the process.