First Published: 11th March 2007

“He’s in a hurry. Be careful here.” That frankly unpromising utterance was Sean Blair’s first line of dialogue in what this year will be a decade’s worth of anonymous work for that great British institution, Commando Picture Library… here, the writer recalls the title’s origins and his own role in its ongoing success…

Douglas Adams wrote that the cosmic success of the The Hitch-Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy could be attributed to the single fact it had ‘Don’t Panic!’ emblazoned on its front in large, friendly letters. Similarly, perhaps the success of Commando can be put down to the fact that each of the 3900-plus issues published over the last four decades has a big dagger drawn on its back.

Commando launched late into a crowded market of war-themed pocket comics: DC Thomson’s first issue came out in 1961, almost three years after Fleetway’s War Picture Library pioneered the genre, aimed squarely at the generation of children who were growing up asking “What did you do in the war, Dad?”

But kids knew what they were getting with Commando. While rival titles bought in their cover art from agencies and stuck in back-up stories as filler, each Commando issue was put together as a complete package – book-length tales of soldiering with a harder edge than the competition — with its lurid cover an integral element.

Their titles also promised a lot more blood and guts. While War Picture Library started off with anodyne names like ‘Up Periscope’, ‘Wings Over The Navy’ or ‘Combined Operation’ – movie versions might have been vehicles for Noel Coward, with John Mills in a supporting role – early Commandos were called things like ‘A Guy Needs Guts’, ‘Mercy For None’ and ‘Hun Bait’. No Noel Coward types need apply!

Rival titles toughened up however, and competition intensified through the 1960s and 1970s. In publishing terms this was full-scale warfare: by 1971 DC Thomson was producing eight Commandos a month — a frequency that continues to this very day — although these were still outnumbered by the opposing Fleetway axis, with Battle and War Picture Library publishing eight and 12 issues a month respectively.

By the early 1980s, the glory days were ending: TV, video tapes and home computer games were winning the struggle for eyeballs, and Fleetway left the battlefield altogether in 1984. Commando was the last title left standing.

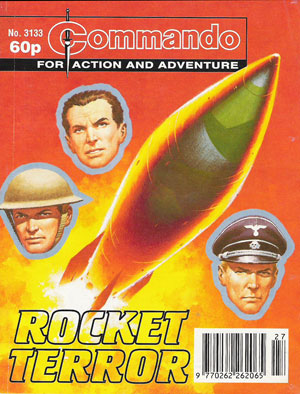

Sean Blair’s first Commando, Issue 3133 – Rocket Terror, his first published script, Ian Kennedy cover and Gordon Livingstone art – blast off! Image © DC Thomson

My little part in the Commando saga started a lot later — in London back in 1997, when I attended an evening class on comics writing, run by the Comics Creators Guild. Maybe a month in, lecturer and comics writer Win Wiacek mentioned that while British comics were in a parlous state (no change there then) – there were a few comics you could still try out for. “You could give Commando a go,” he suggested. “Just imagine you’re writing a black and white World War Two movie.”

Like a lot of people in that class, I was a little surprised Commando was still going. I used to pick up bundles of them from jumble sales (though I preferred the SF-themed Starblazer, when I could find them) but had no idea they were still a going concern, probably because their circulation was spotty down in my part of the country. But getting to write a proper comic, getting paid (a bit!) to write a comic – sounded like a good deal.

Also encouraging was Ferg Handley, who by then had already written his first few Commandos. That involved typing up your proposed plot line then mailing it off to DC Thomson in Dundee – physically, not electronically, in those days, but otherwise the process remains basically unchanged (the pay remains unchanged too, but that’s another story…).

My day job was working as a science journalist and I’d been reading a lot about rocket history, so I put something together about rival rocket scientists – the bad guy ends up working on Nazi V-2 launchers, while the good guy tries to stop him. A week or so later, a typewritten letter came back from editor George Low saying that the idea was promising, but the outline was much too short. He suggested adding in some extra subplots and action sequences, and suggested some possibilities along those lines.

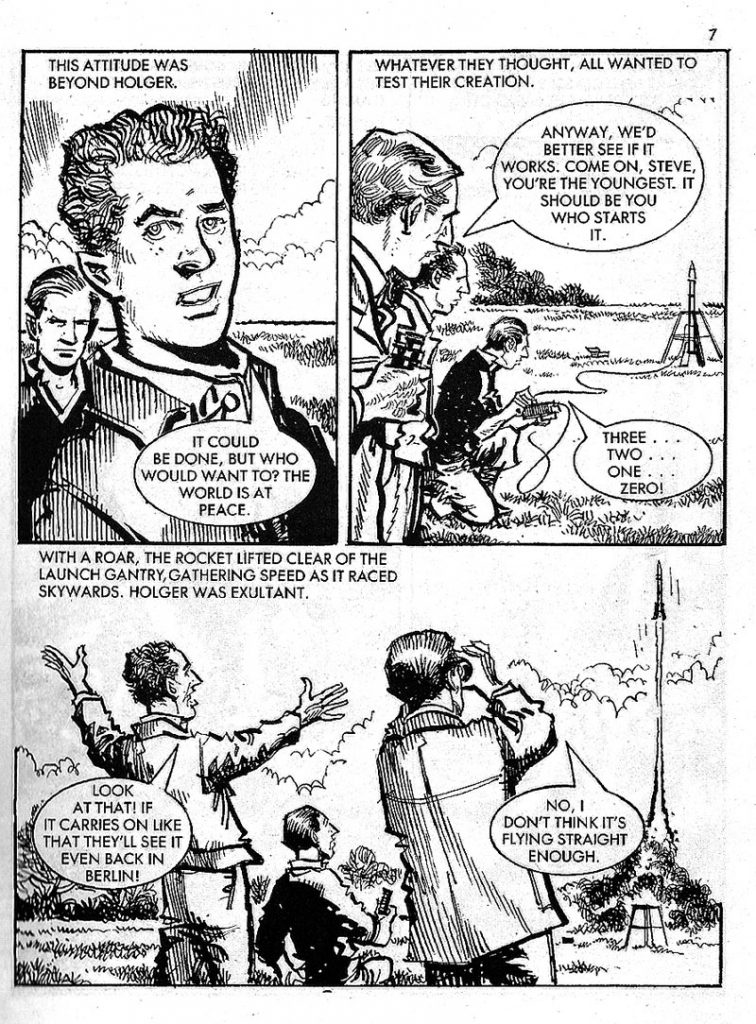

I’d thought my outline was plenty long already, but I’d had the wrong type of comic of mind. A standard Commando script is composed of 135 frames (DC Thomson calls them ‘pics’), which is roughly the same as a 22 page American comic of six frames per page. Except that Commando packs far more plot into those frames — probably because it is the ultimate in compressed story-telling.

There is no “show-not-tell” here. Each and every frame is expected to have a panel caption as well as dialogue – editorial lets you get away with a single panel-free frame once in a while, but certainly not more than one. The captions make sure the storytelling is absolutely crystal clear, and also make up for the lack of sound effects balloons, which simply don’t exist in Commando. The closest you get are the blood-curdling cries of the dying, which one way or another has become the title’s trademark: “Arrgghh!” (I find the exact number of letters differs depending on the severity of the injury).

When it comes to it, Commando really comes from a different tradition than current American comics. These are captioned stories in pictures of a type closer to the likes of Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant or Alex Raymond’s original Flash Gordon in the US. Over in the UK Rupert the Bear is probably the most prominent surviving example of the “picture story” format, whose lineage goes back to Victorian funny papers that Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill referenced in one cover of the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.

Plus, of course, each issue is half the size of a standard comic, with two or more frames per page – so very little room for panoramic art-heavy spreads. George once gently pointed this out when I pitched a “widescreen” story involving a hurricane barrelling into fighting US and Japanese battle fleets. The plot’s the thing! Once I internalised all this, writing Commando got a lot easier (though it took a while).

Anyway, I amped up the V-2 outline accordingly (even stooping to add a V-1 to the mix), and got an agreement by return of post. We were on, and I started writing. Which is when I made my next discovery about writing Commando — it’s an awful lot of work. My scripts rarely come in under 10,000 words and 25 pages (very tough on my aged printer back when I was mailing everything in…).

I’ve written a script in a day before, but it wasn’t a very fun day. More typically, I would write them over about three days. Just to keep your enthusiasm going for what can be a gruelling job, you really have to be dealing with some element you’re particularly interested in: it really isn’t possible to hack Commando stories out one after the other.

Case in point is my third script sold, published as “Kingdom of the Tiger” (Issue 3182): it had paratroopers, a ruthless Japanese enemy and some killer tigers – in retrospect. that was about it. At that stage I was writing the way I assumed Commandos had to be done. Apart from a pretty fun scene near the beginning where the heroes parachute helplessly towards sharpened bamboo stakes it was not so much fun to write, and I notice that — while they accepted it – editorial then pepped up the final version considerably. Learning from that one, in future I tried to push the format to see how far I could go…

I met George for the one and – to date – only time when he came down to visit DC Thomson’s Fleet Street office. He treated me to a few pints one rainy evening and handed me some photocopies of the first few pages of art drawn for my first issue. I was impressed to see it was by an artist whose style I recognised from my own Commando-reading years (actually veteran artist Gordon Livingstone).

It was good to put a face to George, because one of the drawbacks of writing for Commando is the relative lack of communication – the script goes off, then three to six months later comes the complementary copy. There’s little of the back and forth between writer, editor and artist you might expect. The assignment of artists comes down to George, taking into account that certain talents have particular interests they like to follow, such as Keith Page and World War One or Jose Maria Jorge and aviation.

A page from Commando, Issue 3133 – Rocket Terror, art by Keith Page

I’d originally called my first story “Vengeance Weapon”, and it finally saw print as “Rocket Terror” (3133) the following year (they almost always change the title!). It was great to finally have in my hands, even more fantastic to find the cover drawn by the great Ian Kennedy. The main Commando cover artist since 1970s, I had devoured his “Dan Dare” strip each week in the 1980s Eagle. It’s the experience of seeing each new issue in this way that really keeps me doing more.

Not that’s it necessarily easy to do: it could be tough coming up with workable new ideas, and for a long while my outline acceptance rate was less than 50 per cent. Having worked on Commando ever since 1963, George can spot a shaky plot construction at a thousand paces, and has a sure feel for subject matter suited to the target audience of young boys. And after four decades, inevitably a lot of subjects have already been done. For instance, outlines dealing with civil warfare within the French Foreign Legion and plans to use icebergs as aircraft carriers – which I thought were reasonably obscure – were rejected as having been covered previously.

Various ideas got rejected for other reasons. Gas weapons turning World War One trench rats carnivorous was too horrific (plus, James Herbert might have sued!), ditto for a tale of German mad scientists using unstable chemicals to turn raw recruits into supermen. Meanwhile a yarn about spies being buried alive inside a hill to observe enemy activity once the area is captured (based on an evacuation blueprint for the rock of Gibraltar) was judged too visually monotonous.

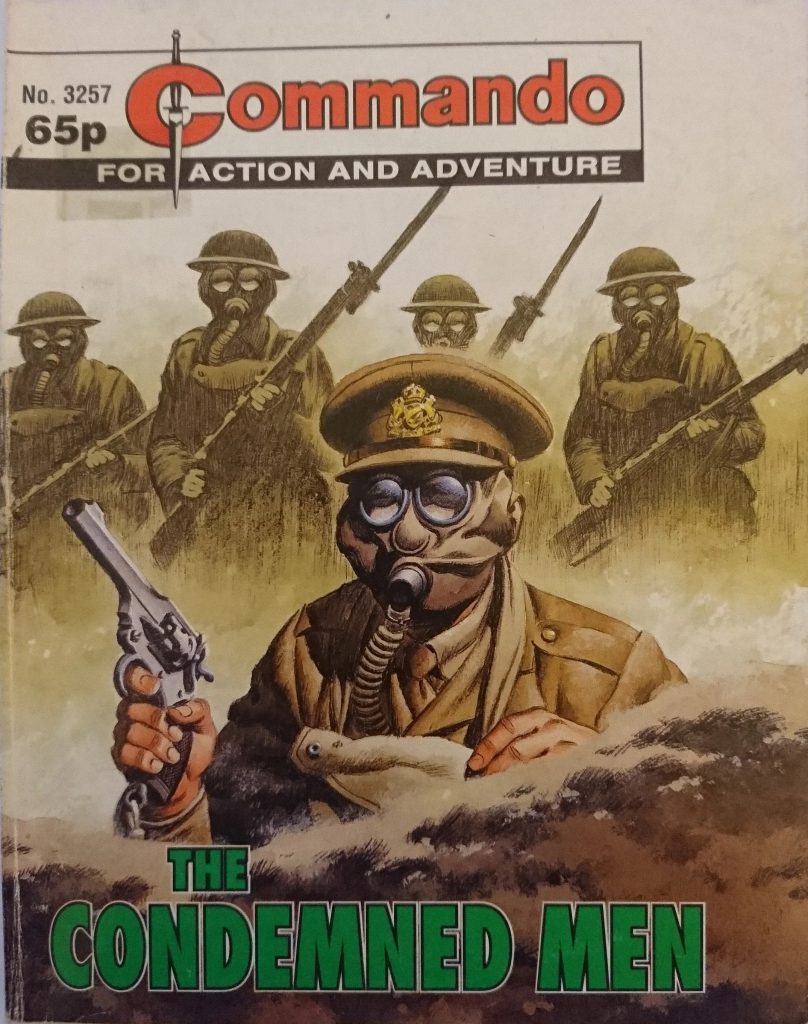

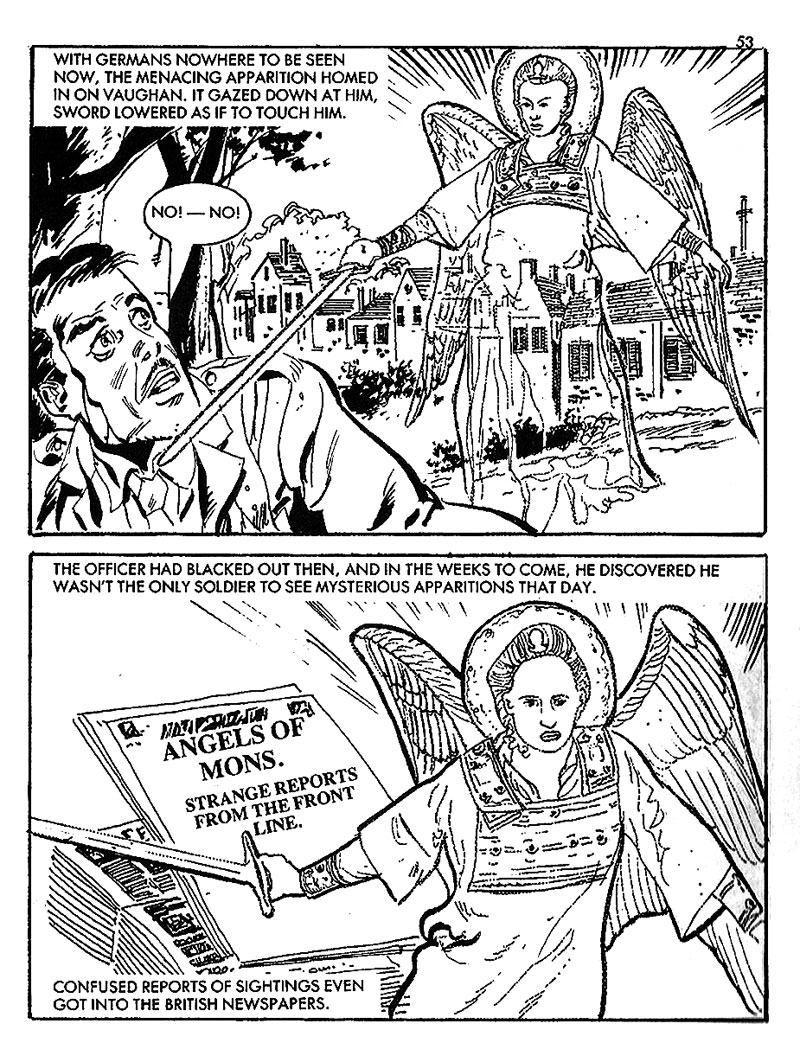

But I was getting happier with the stories that did get accepted: a supernatural World War One tale about what happened when a soldier came face to face with one of the legendary Angels of Mons sustained a pleasingly gothic atmosphere — published as “The Condemned Men“(Issue 3257) – even if the artist’s depiction of the angel was closer to stained glass than the Raiders of the Lost Ark version I had in my mind’s eye.

A page from “The Condemned Men” for Commando 3257, Sean’s favourite story to date

I also had my first go on present-day tales, with ‘International Rescue’ (3239) where a crashed nuclear-powered satellite needs retrieval from an anarchic country that is basically Somalia, and “Programmed to Kill” (Issue 3298) where UAV (Unmanned Aerial Vehicle) technology falls into the hand of an evil drug lord. This latter was my first issue drawn by the excellent John Ridgway, whose fine draftsmanship made the far-fetched hardware seem absolutely plausible.

After a couple of years out when I was travelling then changing jobs, I came back to Commando — for a while I was freelance and after all the extra cash I could get, and DC Thomson pay faster than most! During 2001 and 2002 I wrote something like 14 scripts per year: as many supernatural stories as editorial would let me get away with, present-day or Cold War thrillers and an increasing number of World War 1 stories.

I got interested in World War One partly because World War 2 had been so thoroughly dealt with, but also because of the now-exotic steampunk nature of that era’s military hardware — vast guns, the first tanks, plywood planes and airships. And while the main fronts of that conflict stayed murderously static, there were also a lot of now-forgotten ‘sideshows’ at various corners of the earth. For me the most intriguing was the Allied intervention in post-revolutionary Russia, which for a while threatened to spawn a whole other war of its own.

So, for instance, “Railway Warriors” (3593) tells the story of the Czech Legion who had to fight east all the way across Siberia to get back to their homeland – possibly in rather too much detail, looking back today at all the elongated captions! “Battle for the Baltic” (3655) featured a four-way fight in the post-WW1 Baltic States between invading Russians, defending nationalists, leftover Germans and the Royal Navy.

Like Ferg Handley before me, who wrote a series of tales set back in Roman times, I also went back before the 20th Century. “Pirate Gold” (3629) featured a debauched 17th Century criminal involved in a Caribbean treasure hunt (it came out the same year as Pirates of the Caribbean, but I penned it the year before, honest!). For “The Devils’ Horsemen” (3775) I included the very stage direction they always tell comic book writers to avoid – “Enter 200,000 Mongol horsemen” — but John Ridgway pulled it off admirably.

And with my day job increasingly focused around the space industry, that fed into the stories as well. “Rocket Patrol” (3688) saw a bunch of terrorists try and pull a Die Hard to an Ariane 5 rocket, while I crashed a Space Shuttle in the recent “Shuttle Down” (3971) – probably the closest I’ll ever come to writing a Starblazer. I also fulfilled a long-running ambition by full-fledged nuclear destruction in a couple of issues: “World’s End?” (3662) and “Unseen Enemy” (3678) – although even 24 is doing that these days.

And with my day job increasingly focused around the space industry, that fed into the stories as well. “Rocket Patrol” (3688) saw a bunch of terrorists try and pull a Die Hard to an Ariane 5 rocket, while I crashed a Space Shuttle in the recent “Shuttle Down” (3971) – probably the closest I’ll ever come to writing a Starblazer. I also fulfilled a long-running ambition by full-fledged nuclear destruction in a couple of issues: “World’s End?” (3662) and “Unseen Enemy” (3678) – although even 24 is doing that these days.

But while I might tinker around at the margins, the basic formula of the comic stays the same: underneath the ‘Aiiiee!’s and ‘Gott in Himmel!’s, Commandos are basically school stories, dealing with issues that matter most to 11-year-old boys: the process of making friends, becoming part of a group, learning how to fit in and knowing when to stand out.

My Commando output slowed right down once the demands of my job increased, but I completed the occasional issue to keep my hand in. I had a new flourish last year, when I went travelling in South America. In the email age, all I really needed was a good idea and a net café, and the money from the ten new scripts went a lot further in Bolivia and Argentina!

It’s been fun writing my 50-odd Commandos, I think I’m a better writer as a result, but like Ray Aspden working for Starblazer, there have been some frustrations. The most basic is the anonymity, a long-running DC Thomson tradition, although I try to get around that as best I can by naming characters after friends, family and — in the occasional case — enemies.

It does mean I have a name-recognition factor of precisely zero when it comes to trying out for other comics work — not that I’ve been doing too much of that recently. Where’s to try for? Back in 2001 some “Future Shocks” sent to 2000AD vanished without a trace – although I flatter myself that was because I sent them in on 10 September.

These days there’s some good stuff in the 2000ADs I pick up, but overall it seems pretty inward-looking: maybe they should have changed the title after all. Right now I’m working on a prose novel — however it turns out, I’m sure there’ll be a little bit of Commando in there somewhere.

Meanwhile, approaching its 4000th issue, Commando is still going strong. Foregoing licensed characters or any retreat into specialty stores, Commando is still battling it out in newsagents with nothing more than good stories and art – and shifting a million copies a year.

A switch this year to 50 percent reprinted stories is a little bit of a concern, but even so, that still leaves 48 new issues per year, equivalent to almost a hundred full-sized pages monthly.

The German ambassador may never be a fan, but if aspiring comic writers want to get into print, you could do a lot worse than giving Commando a shot.

Sean Blair

• DC Thomson’s Commando comprise eight digests per month featuring one self-contained war story – available from all good UK newsagents

Article © Sean Blair | All images © DC Thomson