The script for Charley’s War was written by Pat Mills, a name very well known and highly respected in comics today. Pat started his career as sub-editor on romance comics for DC Thomson, before going freelance as a writer. His editorial skills remained in high demand and he was asked to create new titles for Fleetway, including Battle, Action and, of course, 2000AD. He wrote the first ever script of Judge Dredd and his multitude of other creations include Slaine, ABC Warriors and Nemesis the Warlock, along with more recent creatons such as Greysuit and Defoe for 2000AD, anti-superhero Marshal Law for the US market and, in France, Requiem Chevalier Vampire (with Olivier Ledroit).

Charley’s War broke new ground and forged what were really the first steps toward a new direction in writing for Pat that still resonates in the genre today. (The writer Garth Ennis cites Charley’s War as his main inspiration)

Pat’s partner on Charley’s War, the late Joe Colquhoun said this of him: “I think he’s about the best, most painstaking, erudite and factually accurate writer I’ve been associated with. Without his competent and detailed scripts I dont think such a difficult subject as World War One trench warfare could have succeeded.” Mills, as modest as ever, credits all of Charley’s War success down to Joe. Not so.

Mills’ desire to expel the myths of war in general from the minds of its young readership and his want to do justice to the terrible legacy of the Great War can only be applauded.

On this page I will try to point out just some of the interesting plots and subjects handled by Charley’s War. Mills could have written a simple story about World War One: indeed, such was the skill of Joe Colquhoun as an artist that he could have easily carried a lazy script and it still be successful to some degree. What he chose to do instead was write a brutally honest and detailed epic which tackled some of the darker sides of the Great War’s history. There are far too many of these key storylines to go through them all, so this is just a handful.

Some people have accused him of using his writing as a vehicle for his political views – I don’t know about this because I’m unfamiliar with most of his other work (sorry Pat)!But it doesn’t really matter which side of the political fence you are on when it comes to Charley’s War. It’s my view that the storylines below are things that have been pointed out because they are simply wrong and needed to be exposed.

Anyone who has doubts that all the subjects are based on truth should refer to our sources page for further reading. The points made by Mills are a part of a tragic legacy that we should all think about and find out about, to make sure it never happens again. Im sorry to get all heavy about it, but I do feel very strongly about it. Having said all that, the observations below are simply my personal opinion and they could be totally wrong! They are what I take from Charley’s War.

See what you think.

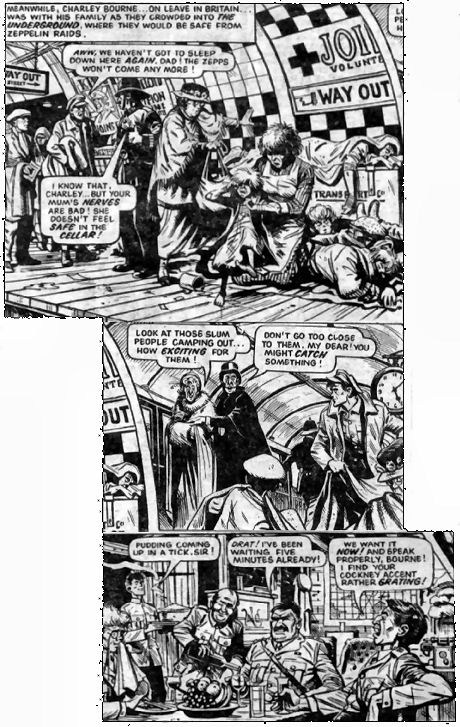

Class

Charley’s War worked on so many different levels in order to make the readers use their own minds to reach conclusions of its many subjects. The thing that strikes me the most reading it now is just how much it attacks the class system of the time. Its foundations are rooted in Class.

Pat Mills seems to drive the point home time and time again, making the usual enemies of war comics become almost allied (British and Germans) and fingers the real enemy as the ruling classes who treated the war as some kind of sport. An enemy within personified by characters such as Captain Snell, Charley’s sadistic company commander.

The subject of Class ran like an artery through the entire story, and the whole depicted a time when an almost mystical patriotism and trust in the ruling classes existed. A trust which was to be sadly abused.

As we’ve seen, the futility of a War promoted by the ruling classes was the main message running through Charley’s War. All the points on this page return to that main theme in some way or another. Charley’s trench existence was almost a microcosm of Edwardian society, the relationship between Officers and men being described almost weekly.

In retrospect, this is possibly the only facet of the plot I don’t fully agree with. Not all the Officers in the trenches were like Snell – in fact very few were, and although the story has good Officers such as Cooper they are still shown as ‘hooray henry’ types (for example Lt Cooper had the …er… impediment every other word in his dialogue-showing him to be indecisive and bumbling). Most officers of the Great War suffered the same hardships that the men did and although it did happen, the image of the Officers eating fresh game in a cosy front line trench while the men died in mud outside are a little over worked. That though is my only grumbling about it in the whole of the six years it ran. The story’s main strength was that it had its foundations always in truth, as we shall see.

Pacifism and Profiteering

Another way of relating the real facts of war was in the use of certain characters who delivered issues to Charley and the reader that were otherwise little known. We see, for example, the upper class, promotion-refusing stretcher bearer character of Jack relating some hard-hitting political views about the nature of profiteering in the war. (His father being a munitions tycoon). The idealistic Charley questions this but the small narratives about “one famous arms manufacturer made three billion pounds profit from the war” and the like confirms the character’s points. (Jack is suddenly killed in the next issue and dies smiling through the clearing smoke. “Charley… it was one of dad’s…”).

Mills used this technique a lot. Budgie Brown is another character who does the same thing (whilst Charley and company are at Messines Ridge earlier in the Ypres battle). Brown tells Charley about conscientious objectors being tied to stakes to be used as target practice by the Germans. Charley becomes hostile and refuses to believe it but yet the narrative that accompanied the frames confirm the story is real. In this way Mills challenged the popular notion (even to this day) that a Conscientious Objector is a coward who is too scared to fight as opposed to a brave individual who will not be made to change his beliefs.

The Imperial War Museum book Forgotten Voices has some excellent stuff on this subject.

We actually see Charley listen and change his views after hearing Budgie’s story. Budgie becomes an equal hero with Charley for a couple of issues because of his unshakeable beliefs.

Fear and Horror

Below is one of the best pages that Joe ever did in my opinion. It concerns the death of Ginger (see next subject) after Ginger is killed suddenly by a shell in front of Charley’s eyes the latter goes into deep shock, or funk as soldiers put it at the time. He has nightmare visions and sees Ginger as ghost sitting on a cloud smoking a fag, demanding to know why he was killed and not the more ignorant Charley.

a surreal question and answer follows between the two which is part black comedy, part heart breakingly tragic. These are great scenes which Mills dedicated an entire issue to, obviously deeming it (quite rightly) an extremely important facet to the legacy of the Great War.

Charley freaks out after Ginger’s death. A hair-rasing page from Charley’s War, from the issue cover dated 27th October 1979.

Death and Loss

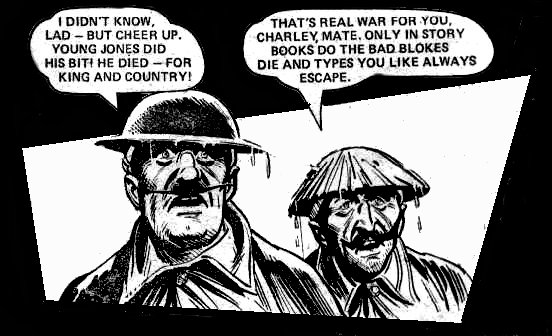

The frames above are the last scenes where we see Ginger Jones-Charley’s best friend. I mentioned on the character page how Mills introduced characters quickly in order to kill them off in order to show the transient nature of the trenches and the appalling casualty rates to his readers. The death of Ginger was the very best example of his ability to shock the reader into thought.

Note the narrative: in its handful of words, it covers the horrific use of high explosive as a weapon, the suddeness of death, and the grief and loss of a friend. It’s truly brilliantly handled and very moving.

One of the most acknowledged scenes of the whole story, one fan is Garth Ennis, comic writer who cites this scene in interviews all the time.

Discipline and Punishment

The script had a knack of forcing the reader to think about subjects such as the barbaric punishments inflicted by the British Army on its own men. This shifting of emphasis away from the crimes of the Germans and onto the more unpalatable conduct of one’s own side was unheard of in British comics, its peers and the period that Charley’s War comes from. The example below is an example of a narrative that accompanies a short plotline dealing with Field Punishment No.1.

This brutal form of punishment was in use by the British Army until the late 1920’s and is basically crucifixion on a gun wheel or fence. The punishment could be extended for up to 21 days and if it coincided with the man’s unit being in the frontline it was was suspended and then resumed as soon as the unit was relieved.

As well as being tied to the wheel for up to three hours a day, the soldier was drilled at high speed in full pack and rifle and fed on bread and water. This cruel and archaic process was done sometimes in range of the German guns.

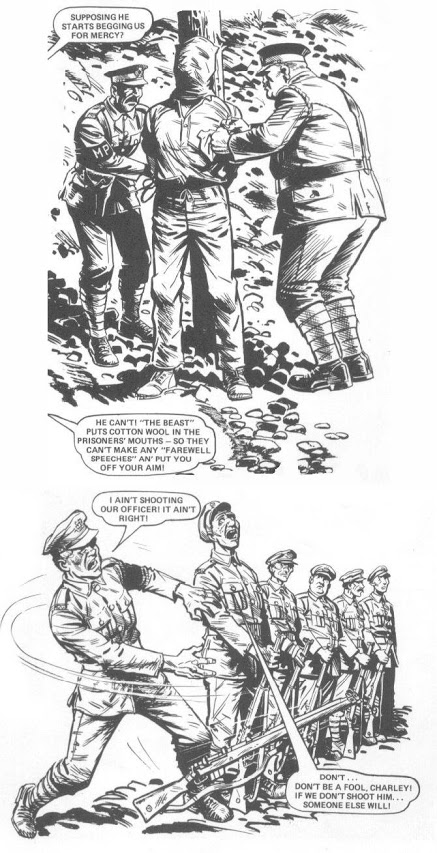

British Executions

Another subject that never fails to motivate anger in me personally is the 346 British soldiers executed for cowardice during the First World War. 80 years after the event, these young guys have yet to earn a pardon and don’t look likely to in the near future*.

Another subject that never fails to motivate anger in me personally is the 346 British soldiers executed for cowardice during the First World War. 80 years after the event, these young guys have yet to earn a pardon and don’t look likely to in the near future*.

Aged bewteen 17 and 26 the soldiers, who inclued one officer, were executed for what we would now term post-traumatic-stress disorder (There’s more background here on the BBC History web site). Naturally, Mills voiced loud his opinions about this ‘official murder’ of our own soldiers with the storyline, which centred on Lieutenant Thomas.

Thomas was the only decent officer we meet in Charley’s War. He cares about the men in his command and because of this he refuses to needlessly sacrifice them in an impossible situation. He was court martialled and shot and, as in real-life his own men are chosen to shoot him. Charley and Weeper refuse, leading to them doing field punishment number one.

A couple of years later, during the Etaples Mutiny, Charley is ordered once more to be part of a firing squad and is called upon to shoot a 17 year old boy called ‘Chatty Mathers’ who is condemned to death for shooting a bullying MP on the rifle range. This time round he reluctantly goes through with it and does as he is ordered.

* Since Neil wrote this feature, 300 soldiers were pardoned in 2006 – see BBC news story – JF

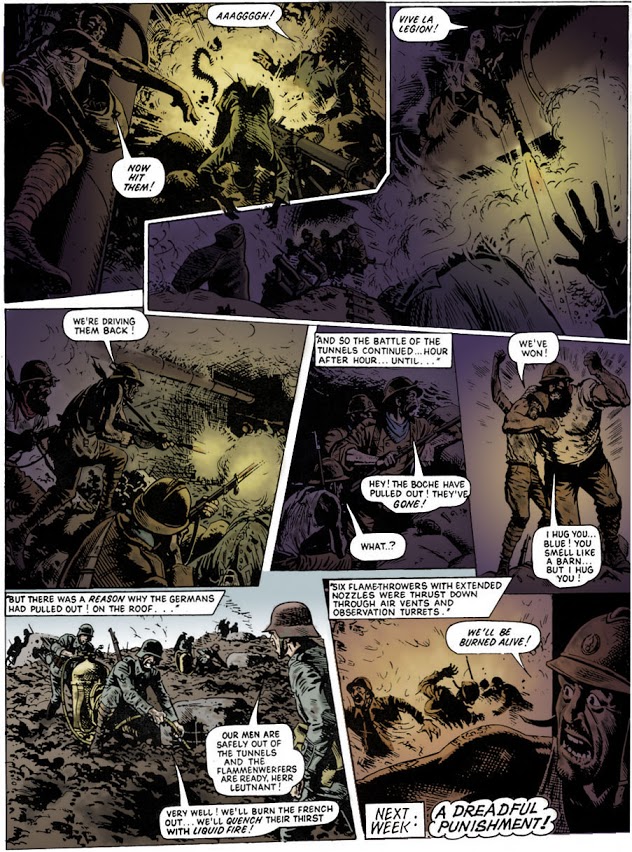

Mutiny at Etaples

Another plotline, which was pretty radical, was the virtually unknown story of the only mutiny the British Army has ever had, at Etaples training ground otherwise known as ‘The Bull Ring’, in France in 1917. Even today 20 years after CW the story is not widely known. The tale of this event is told in Charley’s War with the real-life perpetrator Percy Toplis replaced by Blue. (See the Characters page for his profile) The real story of this event can be read in the book The Monocled Mutineer by William Allison and John Fairley (which the BBC also made into a series in 1986) and although Toplis has recently been proved not to have been at the camp at that time it is one of the most, if not only, in depth accounts of the Mutiny available.

Toplis was shot dead by police in Yorkshire in 1921 after being the most wanted man in England for some five years. He had served bravely as a stretcher-bearer on the western front, in the Battle of Mons, and had deserted after spending a night with a man who was to be shot at dawn for cowardice when he was clearly shell-shocked. Toplis had to take care of the body and the young officer’s effects and this harrowing experience prompted him to desert. He soon became notorious and was considered highly dangerous because he could masquerade as an officer and frequently did to escape capture.

This was, of course highly offensive to the authorities of the day considering that Toplis was an uneducated petty thief from Liverpool and could not be seen to be making a mockery of the brutal, class-orientated British army. The police and military pursued him the length and breadth of the country until he was cornered and killed. Mystery still surrounds his death in a hail of police bullets on a windswept Yorkshire lane.

The story of the mutiny and Toplis’s role in it was covered up at the time.

At Etaples, the mutineers however managed to win the closure of the Bull Ring and eventually the whole camp. For three days 20,000 troops run amok, beating military police and many officers before rampaging through the main square of the town. The actual number of deaths is still unknown.

The mutiny happened just as the third battle of Ypres was beginning causing major concern to the British High Command. The official files on the Etaples mutiny and Percy Toplis are not released until 2017. When the BBC screened the excellent drama of Toplis’s life and death (monocled mutineer starring Paul Magann) there was outrage from the establishment and questions were raised in parliament. The programme has never been repeated for that reason. Information is still being surpressed, the public being deemed as not in need of the truth. Pat Mills says “Charley’s War was great because we slipped through the net, we got away with it, after all who would bother to look in a comic?, and that, of course, was always my intention.”.

The title fame below is the very true event of the stand off at the beginning of the Mutiny on the bridge over the river that led from the camp to the town at Etaples. The source Mills used was the only source for many years about the covered up mutiny – The Monocled Mutineer by Farley and Allison has since been rubbished as wishful thinking in later years for trying to place Toplis in the Camp when it is known he was in prison in England at the time. However this should not let anyone be put off by the book, as the mutiny at Etaples chapters are taken from eye witness accounts of the events and are well researched and well written. The scene concerns the Scots standoff with fifty armed men who had orders to open fire if they did not turn back to camp. Fortunately the Lieutenant in command saw sense and waved them through to the great relief of all involved. They subsequently entered the town and killed two MPs, and smashed up cafes and restaurant. It is also believed two girls were raped by these men. We will know the truth in 2017 when official records are released.

Machismo and Given Roles

Machismo and Given Roles

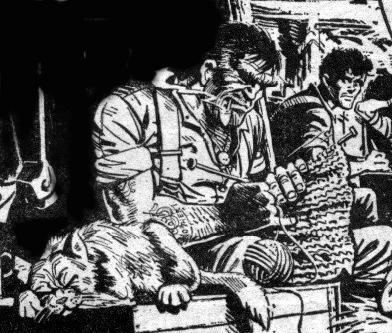

On the left is a frame from the story from just before the Battle of the Somme. The picture shows Mad Mick, a huge Irish tearaway with a big heart. Here he is knitting. I think Pat Mills was trying to show the pointlessness of Machismo. By taking a huge, strong and tempestuous Irishman not afraid to be seen knitting he was playing with what people regard as ‘normal’.

I believe that this is particularly meaningful when you put it in the context of a pro-war comic. Mills’ was constantly playing with stereotypes in the story, from conscientious objectors being cowards, all German soldiers being evil, deserters being spineless, people with a lesser education due to their background being stupid; the examples are numerous. Anyway, I love the cat as well!

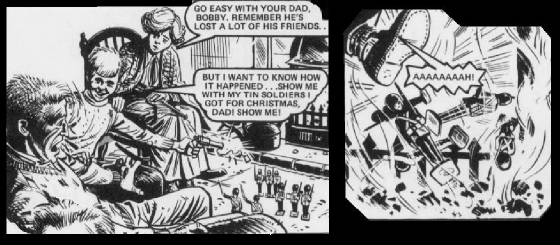

Shellshock

The Mental damage caused by war is demonstrated to the reader in the frame at the bottom of this section. Lonely, an early character, who is posted to Charley and Ginger’s platoon is haunted by the deaths of his original unit which he blames himself for after being the only one to survive. This scene is where he tries to go home on leave and relax after the event. Note the use of the child and the toy soldiers.

On the front page we see Lonely rejoining the ‘lost platoon’, after shellshock has caused a breakdown. Mental damage in war is something that the world of comics had never before (or since) included or even hinted at. These two frames are a perfect example of the writing and artwork working totally in harmony. The frames below in particular in just a few words says so much. It was this special magic Joe and Pat had which made the story so perfect and timeless. It’s as relevant today as it always was, if not more so.

”A young soldier who was so disorientated while he was home on leave, he was entering a London tube station and saw people coming up. He looked hagardly about and mistaking the tunnel below him for a dugout full of Germans he fixed his bayonet and charged at them, if it were not for a quick thinking wpc who grabbed him and held on for dear life, there would have been many deaths and injury” – British pioneer policewoman Mary Allen in her Autobiography.

“We saw a handful of soldiers, commanded by a Captain, slowly approaching, one at the time. The Captain asked which company we were and then all of a sudden started to cry. Did he suffer of shell shock? Then he said: ‘When I saw you approach it reminded me of six days ago, when I walked this same road with approximately hundred men. And now look how few there are left…’ We watched as we passed them; they were about twenty. They walked by us as living, plastered statues. Their faces stared at us like shrunken mummies, and their eyes were so immense that you could not see anything but their eyes.” –German Officers letters 1917

Prejudice

Here, we see a colour cover from 1981. (Many thanks to Richard Moyles for the image). The story concerned French Senegalese soldiers who were sent into the line at Verdun to test the German’s line. These troops had never seen a machine gun before and suffered huge losses.

It wasn’t the last time that Mills tackled the tricky issue of race in the story. Much later when the American army entered the War we see Charley observing the treatment of Afro-American troops by their white peers. The British Army was certainly not innocent of these practices either. The Indian, Jamaican, South African and even Australian troops in the British Army were treated equally badly.

Up until two years ago, the Indian and Jamaican veterans had no Memorial anywhere in this Country to honour their dead. The British West Indies Regiment in the First World War consisted of 15,601 troops they saw action in France and Egypt and by the end of the War they had won 37 Military Medals, eight Distinguished Conduct Medals and nine Military Crosses, and yet where is their mention in the official histories? These men were not press-ganged into the army – they volounteered to fight for the ‘mother’ country they had learned about in school. Some stowed away on ships to join the British Army and fight its enemies.

After the War, the Disfigured and Maimed amongst them received no Pension due to the War Office, deciding that they were not British. There’s details on the links page for a website dedicated to them.

Pat Mills, using the different angles he did to prove the futility and waste of war (a few of which I mention on this page) wrote a script that was both brave and unequaled in a comic of its time and, arguably, ever since. Charley’s War was a mini-revolution, a Trojan horse of sense in a war comic. In a time when war was portrayed as glorious and exciting by hero’s who were the epitome of bloodthirsty machismo directly to a readership of impressionable young boys eager for escapism, Charley’s War was a tiny part of the real world, with real history, real sadness and real horror.

Charley’s War was a tiny Oasis of truth in a pro-war comic, it simply was a classic in every way. Inexplicably it remains one of Pat Mills’ least known works. To its devout and dedicated fanbase, it remained for many years a wonderful secret. Now it’s time to share it.

In a scene from about the third episode Charley runs into no man’s land to rescue a wounded man. Old Bill shouts a warning to him to stay put due to a German sniper. “You ain’t no hero in a penny comic, Bourne!” How true.

Neil Emery

Charley’s War created by Pat Mills and Joe Colquhoun

CHARLEY’S WAR ™ REBELLION PUBLISHING LTD, COPYRIGHT © REBELLION PUBLISHING LTD, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

What a fantastic article! I came here via an article in the Guardian about an upcoming exhibition of comic art from this period, which mentioned Charley’s War. I’d never heard of it, having come to comics with the first issue of 2000ad. Your thoughts have made me determined to find a compilation of CW. To think that these comics were for kids! It’s quite something.

So, thanks for taking the time to write so movingly.

James