Britain’s National Archives is a wonderful repository for many odd things, but you might be forgiven for wondering just what a number of horror comics might be doing lurking in its catalogue. It was certainly a surprise to researcher Emily Stidston, who found a number of them attached to official 1950s government correspondence – Prime Minister’s papers to be precise.

Of course, some comics fans will know that the archived comics were part of government concerns in response to fears about the impact US horror comics were having on children, and a then secret memo circulated to the Prime Minister and the Cabinet in November 1954 notes that deputations from the Education Institute of Scotland, the Glasgow Corporation and the Church of England Council for Education (which was led by the Archbishop of Canterbury) had “urged that the Government should introduce legislation to deal with the matter, and a resolution to that effect has been passed by the Church Assembly.

The memo also notes that the National Union of Teachers had recently staged an exhibition in London which displayed, without any attempt at sensationalism, “some of the worst examples of these comics together with examples of well-known children’s comics and newspapers which are regarded as harmless”.

A self-appointed Comics Campaign Council founded in 1953 by leading pediatrician and Communist Party member Dr Simon Yudkin battled to bring their concerns to the attention of the government and serving to unify the disparate protest groups, gathering support among professionals such as doctors and teachers, issuing pamphlets, holding public meetings and submitting opinion pieces to various national news outlets.

Responding to growing concerns, Prime Minister Winston Churchill was sent seven examples of 1950’s US comics along with the memo as supporting evidence to a child protection bill, in connection with proposed legislation to prevent the publication and sale of horror comics to children.

One wonders what he made of the titles he was sent, which are an eclectic mix of US imports, UK published collections of US comics material and one Australian import.

They’re certainly an eclectic mix. One has to wonder, for example, what was so terrifying about a British edition of the popular US title Casey Ruggles Western Comic, reprinting the eponymous newspaper strip created by Warren Tufts and yet, Emily notes, “this seemingly innocuous picture book was seen, at the time, as contributing to the downfall of Britain’s youth.

“Well-meaning parents and responsible citizens across the UK saw these ‘horror comics’ as harmful to children – apparently encouraging low moral standards, violent crime and delinquent youth behaviour.”

Based on information on the comic in the Grand Comic Database, the title seems an odd choice as just 47 issues were published and it would appear that it was no longer even being published in 1954. Today, notes comics archivist Don Markstein, “the Casey Ruggles strip is as well-remembered by aficionados of newspaper comics as it is forgotten by the general public.

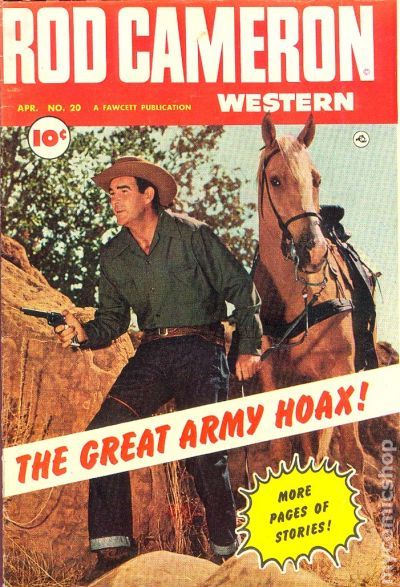

The issue of Rod Cameron Western – again, apparently a British edition of the title published in the US by Fawcett (utilising an image used on the US #20 for its cover), seems similarly ill deserving of being singled out for government displeasure. The comic was based on the many popular westerns of the day starring the Canadian-born film and television actor whose career extended from the 1930s to the 1970s.

Jesse James Brings Six Gun Justice to the West is another cowboy-themed title singled out for criticism, a 100 page giant comic book from Avon Publishing released in 1952, featuring art by Joe Kubert and Everett Raymond Kinstler. You can buy it on eBay if you’re curious, if you have a spare £100.

Famous Yank Comics is another oddity in the circulated examples, since it is actually an imported Australian title, albeit utilising US comic material, published by Sydney-based Ayers and James. However, its crime-filled page would certainly push the buttons of concerned parents.

Frankenstein Comics #2 is, perhaps, more the kind of title that had parents and organisations in a a lather, given its horror-packed pages, which as an out of copyright title, you can read in full on Comic Book Plus. Today, the tales seem almost moral, featuring a gang of greedy men getting their just deserts, a vengeful plant and a mysterious Shangri-La-like paardise.

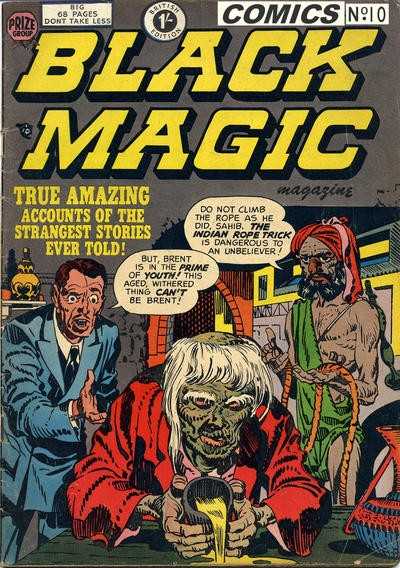

Similarly, Black Magic Comics is the kind of title that drew complaint on both sides of the Atlantic (in the US, such comics saw the introduction of the Comics Code in 1954 and the ‘death’ of horror comics there). Again, the example in the archive is a British edition of the Prize Comics title, featuring art by Jack Kirby and reprinted in Titan Books excellent The Simon and Kirby Library – Horror coillection.

But what about poor Captain Marvel, published under licence from Fawcett in the UK by L. Miller? What did he do draw the eye of concerned civil servants in the L. Miller-published collection sent to the PM, other than to “Face Fear”? The issue seen by ministers was one of its then weekly editions, but its “Marvel” range had already fallen foul of the long-running end to a 12-year legal dispute in the US that saw Fawcett Comics cancel all of its superhero-related publications. Indeed, the end of “Captain Marvel” had already prompted the creation of British superhero, Marvelman, by Mick Anglo. The issue features a daft story about Captain Marvel foiling Fear, encountering a country boy with a bag of gold who thinks he’s a thief – and the superhero being bullied by a couple of imposters making his alter-ego Billy Batson’s boss’s life a misery. All harmless stuff. You have to wonder what Winston Churchill, who’d brought Britain through the horrors of World War Two, made of it all.

Whatever we might think about these comics now, so great was the concern about that in 1955 Parliament passed The Harmful Publications Act (Children and Young Persons), seeking to protect the nation’s innocence.

The Act, which is still on the statute books, applies to any book, magazine or other like work which was of a kind likely to fall into the hands of children or young persons and consists wholly or mainly of stories told in pictures (with or without the addition of written matter), being stories portraying the commission of crimes, acts of violence or cruelty; or incidents of a repulsive or horrible nature in such a way that the work as a whole would tend to corrupt a child or young person into whose hands it might fall.”

Those breaking the law faced imprisonment for a term not exceeding four months or a fine and, of course, the offending comics would have been destroyed.

Despite the furore of the time, and although some comics were “outed” by the Comics Campaign Council as examples of morally corrupting work, the organisation pushing for prosecution of the publishers, of those cases were referred to the Director of Public Prosecutions, only two prosecutions were made under the terms of the Act- in 1970, just after it had been abolished.

The parliamentary record, Hansard, does not detail what these were, although further research reveals one was successfully brought against publisher L. Miller in 1970, but I’m guessing the prosecutions weren’t for Casey Ruggles or Captain Marvel…

Further Reading…

• Pulp Demons: International Dimensions of the Postwar Anti-comics Campaign edited by John A. Lent has more information on the Comics Campaign Council. The book offers essays on the censorship of violence and political comment in comics in the US in the 40s and 50s which sparked similar campaigns in other countries.

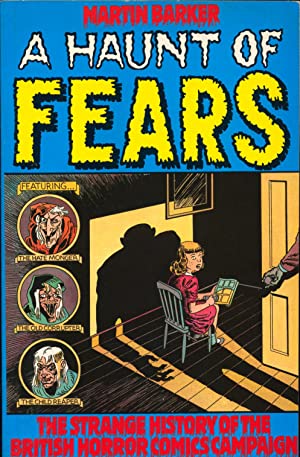

• You could also try tracking down the brilliant Haunt of Fears by Martin Barker. His book explores the British 1950s anti-comics campaign by asking some rather different questions. Who were the people at the heart of the anti-comics campaign? Why and how did the British Communist Party come to play a central role, and yet end up attacking a group of comics which were “on their side”?

• View all the titles Winston Churchill was sent to read here

• Over on his Blimey! It’s Another Blog About Comics, Lew Stringer has a feature on some of the newspaper headlines of 1954 about the “horror” of “horror comics”, and another great item here – “The year Britain got the Horrors over Horror Comics”

Watch: Dave Dustin – The 1950’s British Comics Campaign against American Horror Comics

For anyone interested in the history of comic censorship in the UK, Dave Dustin created this YouTube video in 2022, taking a look at all the British anti-comics propaganda. All the way from the books Juniors and Children’s Comics by George Pumphrey to the booklets Lure Of The Comics, Comics And Your Children, and British Comics An Appraisal, to the 1956 conference From Comics To Classics… and everything inbetween

With thanks to Richard Sheaf for his discovery of The Lure of Comics pamphlet on eBay, added to this article in 2021, and Lew Stringer for additional links, added 2024

Categories: Featured News, Features, US Comics

Adam Eterno sparks some Memories: Which Comics Did You Read Growing Up?

Adam Eterno sparks some Memories: Which Comics Did You Read Growing Up?  The British Comics Industry: Looking Back on 2015, Looking Forward to 2016

The British Comics Industry: Looking Back on 2015, Looking Forward to 2016  Arcadia Bound: An Interview with Writer Alex Paknadel

Arcadia Bound: An Interview with Writer Alex Paknadel  London Super Comic Con 2015 – A DownTheTubes Photo Report

London Super Comic Con 2015 – A DownTheTubes Photo Report

There was a church guy in the UK called Pumphrey John who corresponded regularly with Frederick Wertham for a number of years who passed on images from Wertham to church groups, women’s groups and boy scout leaders etc. He also wrote to parliamentarians about the issue as well.

Like many other 1950s critics such as Geoffrey Wagner, George H. Pumphrey did not like comics, either in form or content. This included Eagle, which in part was a reaction to concerns about US comics, which he condemned in his writings, and in an angry letter to the Spectator in 1956, After a review of one of his books by Kingsley Amis (http://archive.spectator.co.uk/article/6th-january-1956/16/childrens-comics – subscription required).

In this academic text by Ignacio Fernández Sarasola (https://journals.openedition.org/belphegor/798?lang=en), it’s noted that at one point that in the 1950s, thanks to the growing campaign against comics, two out of three Britons seemed to be in favor of banning that genre of literature. This was helped by the breadth of the social campaign, which was echoed even by the United States and which was cleverly orchestrated: press, radio, television, pamphlets, books, exhibitions… A whole list of formulas at the service of the same goal: stop that “poison that is spreading to pollute the minds of British children”.

George Pumphrey was director of a primary school in Sussex County, and his first approach to comics – as he himself related – had taken place when he was looking for reading material for students. It was then when he ran into a copy of Eerie, a comic of the horror genre that had seen the light in the United States in 1947, then published in England in 1951.

Sarasola notes Pumphrey said he was horrified by the content of those truculent stories told through of shocking images where wolf-men, undead and assassinations followed one another. The British educator then engaged in an intense work of disclosure about the damage that comics caused in the weak psyches of minors. This is how his three best-known works would come to light: Comics and your children (1954), Children’s comics: a guide for parents and teachers (1955) and What children think of their comics (1964). The first of these, in addition, would serve to publicize the activities of the Comics Campaign Council, born in 1953 from the London Federation of Parent-Teachers Association.