Review by Tim Robins

I watched Peter Hujar’s Day to continue detoxing from Avatar: Fire and Ash. A chamber play of sorts, the film is based on the transcript of an interview between the photographer, Peter Hujar, and writer Linda Rosenkrantz.

Conducted in 1974, the pair name drop a veritable who’s who of the contemporary New York ‘scene’, including Susan Sontag, Lauren Hutton, William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg and Fran Lebowitz. It’s a long list but it hardly exhausts their social circle. Rosenkrantz herself partied at Andy Warhole’s Factory, and, by the time of the interview, had already published her novel Talk (1969) based on conversations with two of her friends.

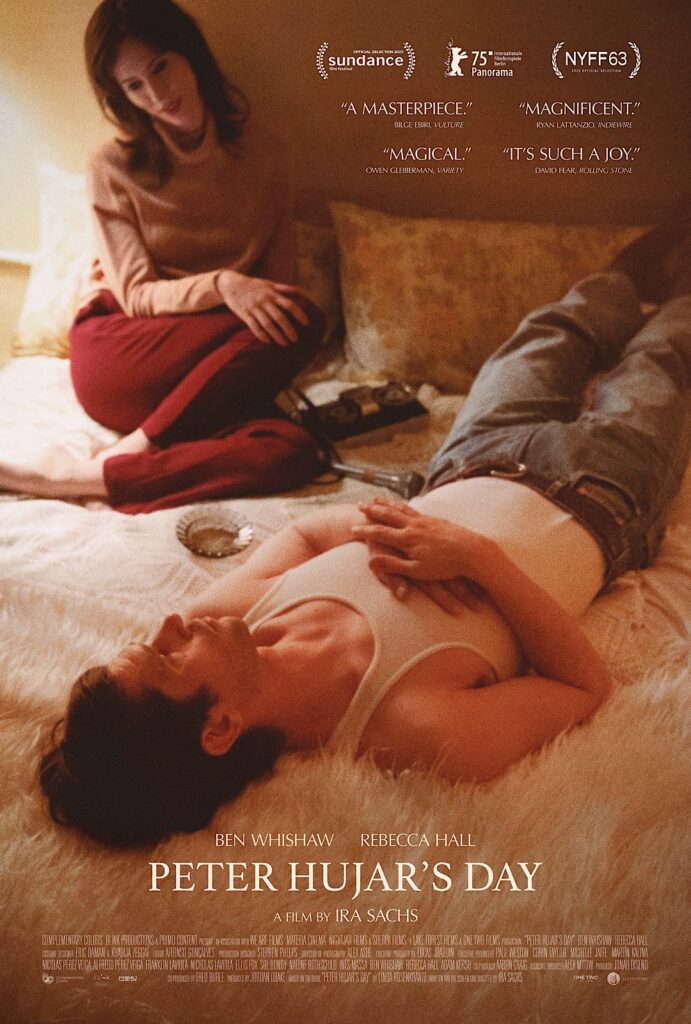

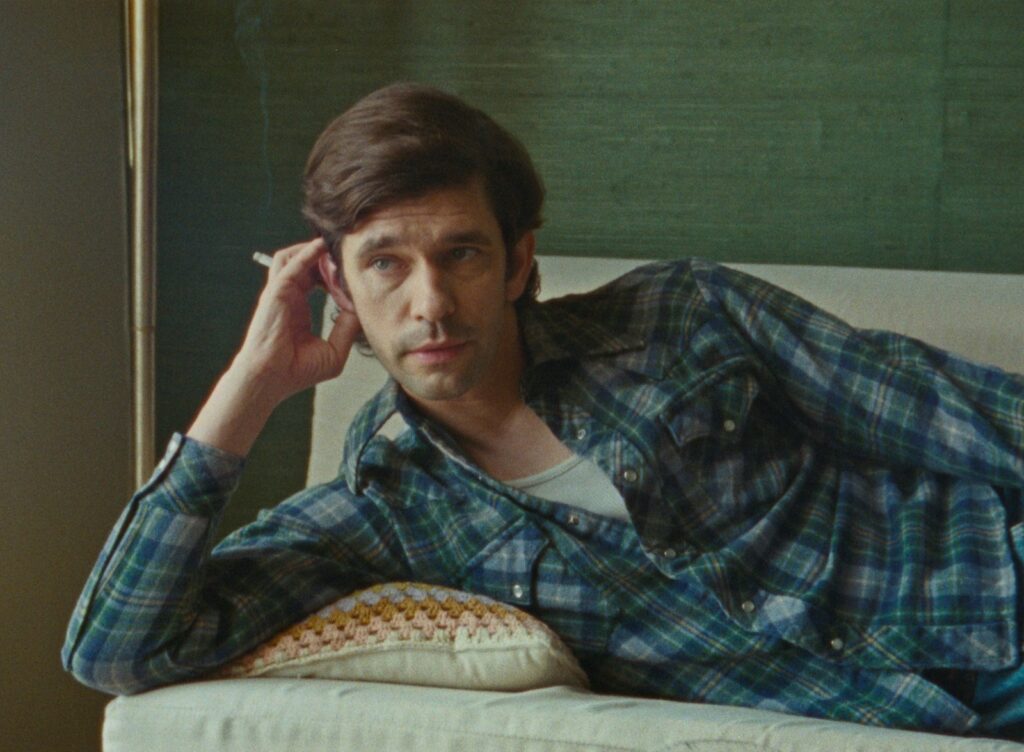

I feared the film would be insufferably pretentious. That it isn’t, at least not insufferably so, is thanks to the beguiling performances of Ben Wishaw, as Hujar, and Rebecca Hall as Rosenkrantz.

I can’t vouch for the authenticity of the British performers’ American accents, but they sound fine to me. Reportedly, director Ira Sachs was convinced to produce a feature-length film thanks to Wishaw’s passion and insight into the language initially, “Every word counts,” Sachs recalls, and Wishaw “conveys that, so there is an interest that seemed complete to me, and I wanted to see it through.”

While Wishaw had 55 pages of dialogue to recall, Hall had only three. But that doesn’t diminish her presence in the film. Rosenkrantz had asked Hujar to recount a day in his life – 18th December. Hujar forgot to make notes, and reconstructed the day from memory.

Sachs structures the film so that the interview also lasts a day, beginning with Hujar’s arrival at Rosenkrantz’s apartment and closing with the pair looking at the sun setting over New York. The interview finally ends when Hujar begins to nod off.

The director sticks to the situation of the interview, Rosenkrantz’s New York apartment, and it becomes another of the film’s attractions. The living space is effortlessly tasteful, containing carefully poised mid century furniture, fashionable again today.

Filming was conducted at the city’s Westbeth Artists Community, which, since the 1970s, has provided low cost living and exhibition spaces for artists of all kinds. Rosenkrantz rented her own apartment on 94th Street. In Sachs’s hands, Her apartment is turned into a cosy, intimate, safe space in which to stage the flirtatious relationship between interviewer and interviewee.

My friends and I – all currently sofa surfing or living in tiny flats or rooms in Brighton – were left wondering how great it must have been to have such a place, at such a time and at such low rent. “But let’s get real,” Stephen Koch admonishes in his prologue to the published interview transcripts, “The Lower East Side was also a slum, and in places it was a genuinely scary and nasty slum.”

The director also explores the physical relationship between Hujar and Rosenkrantz, as they deport themselves around the flat across the day. In a spontaneous, heartwarmingly funny moment, Hujar and Rosenkrantz dance to TennesseeJim’s, “Hold me Tight”. It’s the most American cultural moment in the film. It is as if Hujar and Rosenkrantz are courting each other on a dance floor on a night out. The pair end up sprawled across a mattress, Hujar affectionately resting his head on Rozenkrantz’s shoulder.

The idea of professional encounters as an opportunity for seduction is established early on in the interview. Hujar recalls that his day began with a visit from an editor, a woman, from Elle. “Now somehow in this time I’d also had the fantasy of being seduced by the Elle girl…she was going to come in and it was like in a French movie and it would happen right there… She would be raunchy and reach for my buttons… I thought it might be terrific right then in the morning, very French.”

“Anyway”, Hujar notes matter of factly, “she comes in and she’s short…”. The seduction doesn’t happen, although his recollections did lead me to wonder whether Hujar and Rosenkranzhad similar fantasies about each other.

Sachs plays with blurring the boundaries of fiction and reality right from the get-go. The film starts with a shot of the clapperboard being snapped shut as Wishaw exits the lift and later we get a shot of the crew supposedly at work.

Hujar turns out to be an unreliable narrator, often stopping to admit some of his recollections are lies. And we never see his photographs, so they don’t provide evidence of people, places and events. It occurred to me that Hujar’s and Rosenkranz’s entire social scene could well be invented. This is underlined by a discussion of a celebrity musician called ‘Topaz Caucasian’, who was entirely invented as an in-joke.

In one scene, Hujar, then Rosenkrantz, look directly at us. This mimics Hujar’s photographs, particularly his own self portraits. But characters making direct eye contact with the audience is also a challenge (exemplified by Tippi Hedren in The Birds). The pair confronted us from out of the past, daring us to judge them from our point of view in the future. “Hujar’s photography embodies ‘shameless shamelessness,’ challenging viewers’ perceptions of vulnerability and intimacy”, concludes Harrison Adams in “Peter Hujar: Shamelessness Without Shame”, available via Academia.

For all the humour and defiance, Peter Hujar’s Day is tinged with melancholy. Near the film’s end, Hujah separates himself from Rosenkrantz, to sit on some stairs. He stares at her from behind a balustrade. The struts seem to form prison bars. He sits isolated in time and place, alone as if trapped by fate.

Hujar’s destiny was to be different from that of Rosenkrantz. Rosenkrantz is not dead. Hujah, was a gay man and HIV positive perhaps even at the time of the interview. He was to die in 1987 from HIV related pneumonia.

In this context, Hujar’s complaints of breathlessness and tiredness carry an inevitable sense of foreboding. AIDS was only identified in 1981. Hujar attributes his symptoms to chain smoking. He says, “I have smoker’s hangover all day long.” When he says that he has wasted time, only we know how little he has left.

At just 75 minutes, Peter Hujar’s Day, is long enough to be an absorbing, affectionate snapshot of another place and time.

Tim Robins

Head downthetubes for…

• Photographer Peter Hujar | The David Wojnarowicz Foundation (wojfound.org)

• Peter Hujar’s Day (AmazonUK Affiliate Link)

• Peter Hujar’s December 18 – The Allen Ginsberg Project

• Images – The Peter Hujar Archive

Categories: downthetubes News, Features, Film, Other Worlds, Reviews

In Review: All You Need is Kill (2025)

In Review: All You Need is Kill (2025)  In Review: Good Luck, Have Fun Don’t Die

In Review: Good Luck, Have Fun Don’t Die  In Review: 28 Years later: The Bone Temple

In Review: 28 Years later: The Bone Temple  In Review: Avatar – Fire and Ash

In Review: Avatar – Fire and Ash