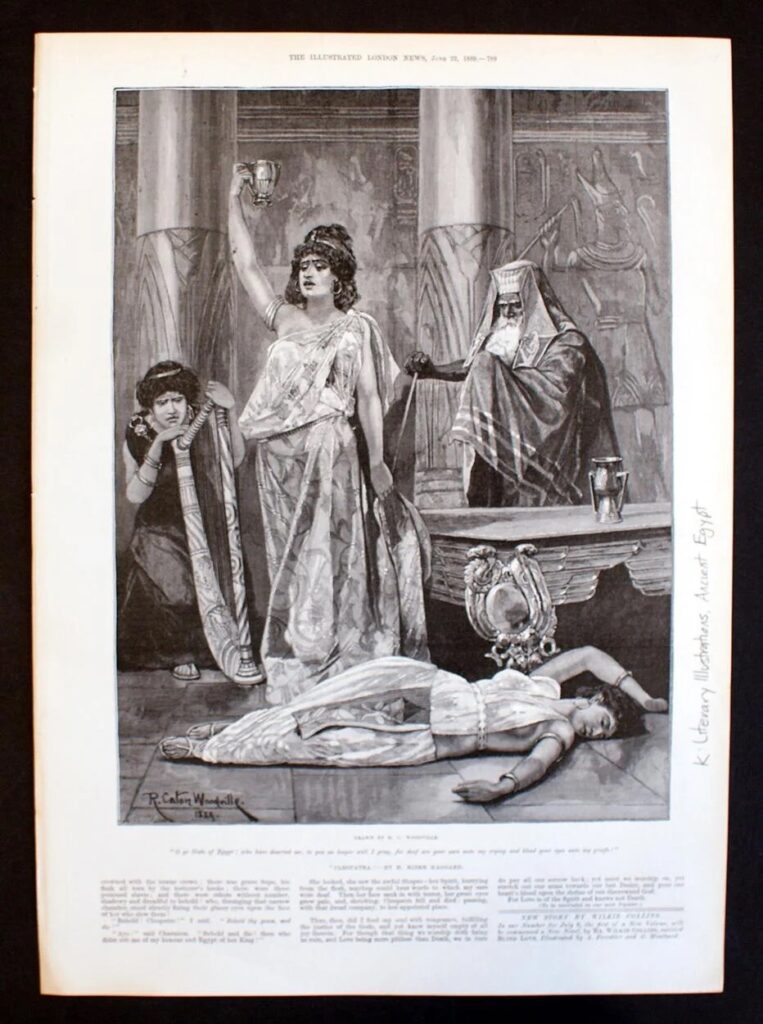

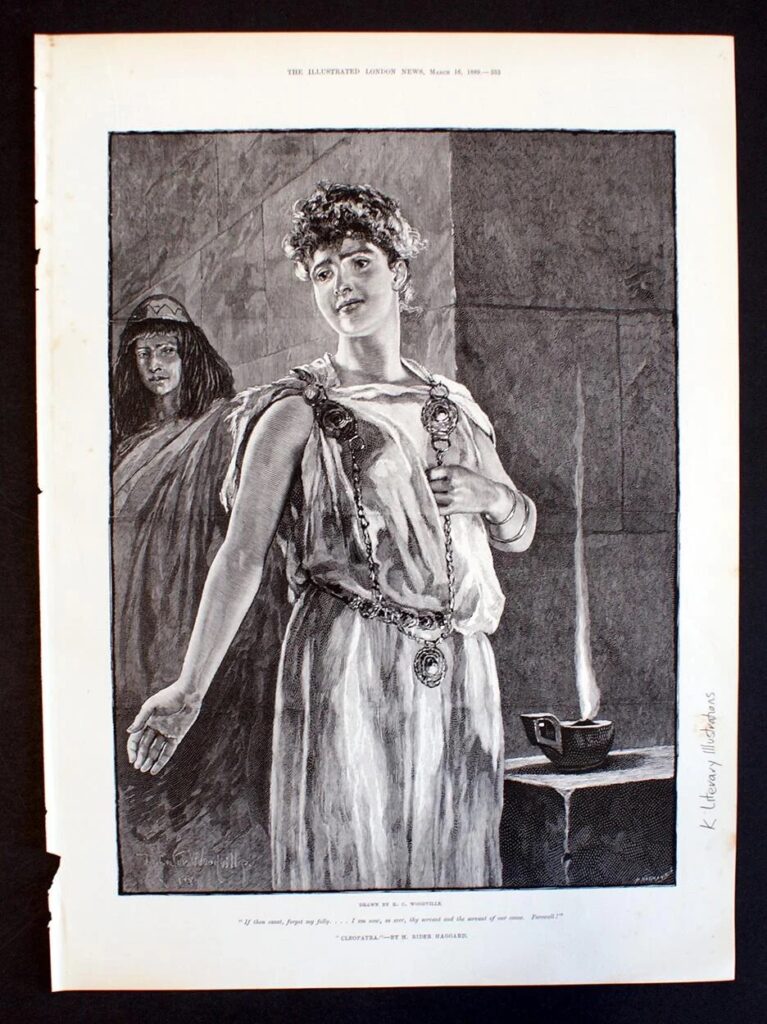

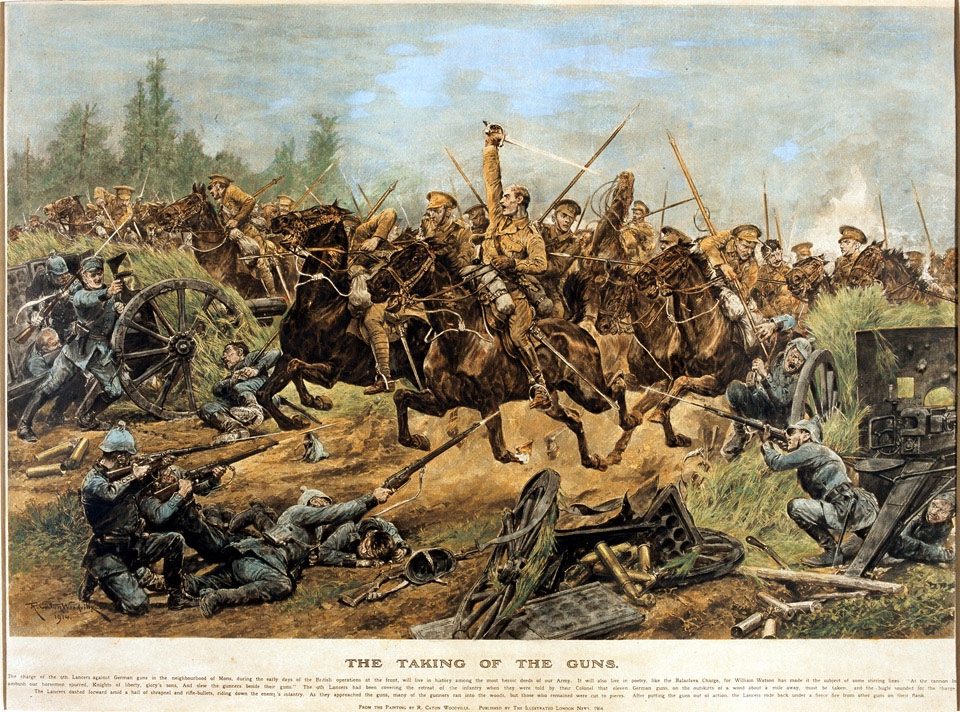

The Book Palace currently has a number of prints for sale by the much admired, but very troubled war artist Richard Caton Woodville Jr., taken from the pages of The Illustrated London News.

The Illustrated London News, founded by Herbert Ingram and first published on Saturday 14th May 1842, was the world’s first illustrated weekly news magazine. It was published weekly for most of its existence, switching to a less frequent publication schedule in 1971, and eventually ceased publication in 2003.

The company continues today as Illustrated London News Ltd, a publishing, content, and digital agency in London, which holds the publication and business archives of the magazine.

Richard Caton Woodville Jr. (7th January 1856 – 17th August 1927), the son of Richard Caton Woodville Sr (1825-1855) an American artist and the son of a stockbroker, was a widely recognised and prolific artist, but his personal life appears to have been troubled, his relationships with his two wives a disaster on both sides – and his life ended in depression and tragedy.

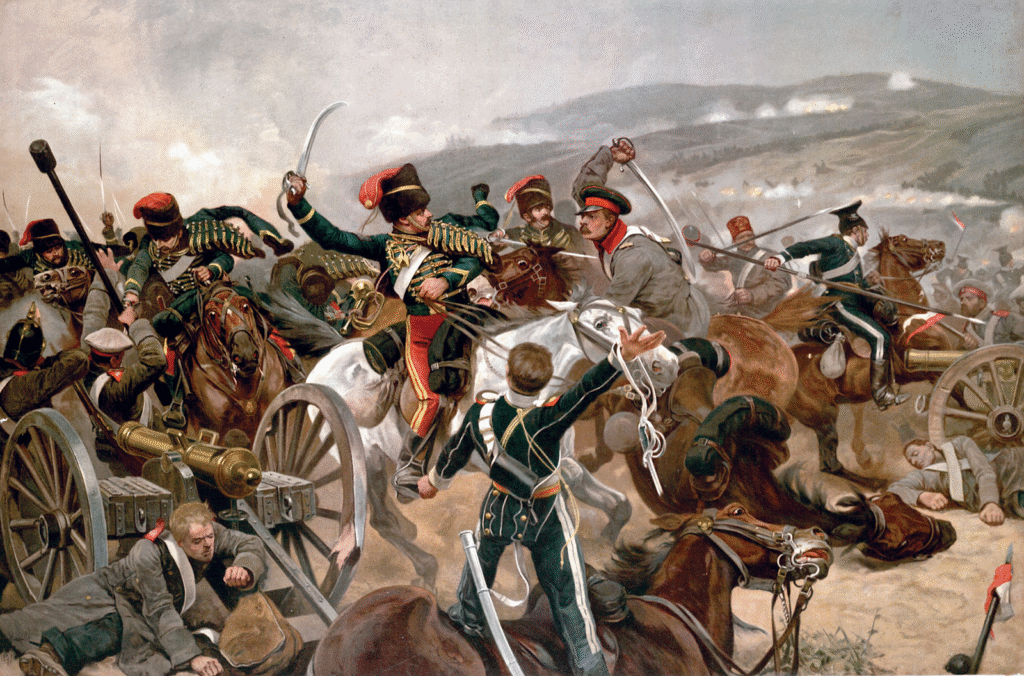

Woodville is particularly remembered for his battle scenes and many of his paintings are in military art collections, such as the National Army Museum, the Royal Naval College, the Royal Canadian Military Institute, the London Scottish Regiments Museum Trust and West Point, as well as national collections such as the Tate Gallery.

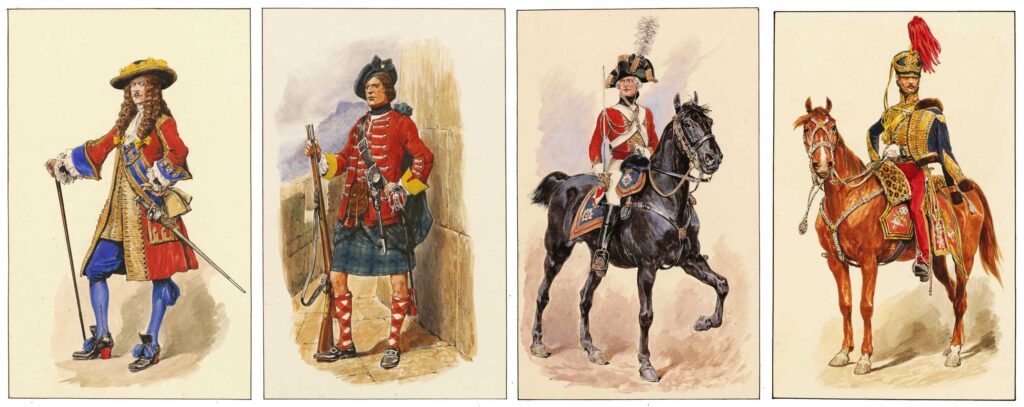

He recreated battle paintings from his imagination, but his attention to the details of uniform made them appear authentic, maintaining a large collection of arms and uniforms in later life.

Personal Perfidy

In 1845, aged 20, he left Baltimore to train at the Kunstacademie in Düsseldorf, Germany, learning from teachers that included Wilhelm Camphausen and Eduard Gebhardt. where he lived for the next six years with his first wife, Mary Theresa (nee Buckler), who he married on 3rd January 1844.

He married his second wife, Annie Elizabeth Hill, on 15th October 1877 and had twin sons, actor Anthony Caton Woodville (husband to actress, Dora Barton) and painter William Caton Woodville, in 1884. But he deserted her in 1889 and moved from London to Aldershot, and, when his wife sued him for divorce, she explained in court that he had written her a letter declaring his married life had been a mistake and he would not come back. By the time of their divorce by decree nisi, with costs, he was living in Paris with another woman, according to Frédéric de Haenen, a French artist who also worked for the Illustrated London News, who gave evidence in court on Woodville’s behalf.

It appears he had also neglected to divorce his first wife: that finally took place in 1901, through courts in Nebraska, various papers reporting separation “on the grounds of cruelty”.

Wikitree notes Anthony and William had a half-sister, Lily Antoinette Helen Yvonne Caton Woodville, the name of her mother not documented.

His personal finances were a mess, too: in 1905, he was declared bankrupt, with debts of some £11,000 and assets of just £189. In newspaper reports of proceedings at the London Bankruptcy Court, he admitted his failure was due to his having beyond his income.

A Much Admired War Artist

Despite the mess his personal life appears, his career as an artist was impressive. In 1879, his first painting, “Before Leuthen Dec. 3rd, 1757” was exhibited at the Royal Academy and, over the next few years he produced many popular paintings, amongst them “Kandahar” and “Saving the Guns” at Maiwand (both inspired by the Second Anglo-Afghan War), and many scenes from the Zulu War and First Boer War.

His painting “The Moonlight Charge at Kassassin” was exhibited at the Fine Art Society in 1883 and “The Guards at Tel-e-Kebir” was exhibited by Royal Command in 1884. The latter was painted for the Royal Family in 1882, and led to a number of further commissions, including the wedding of Princess Beatrice to Prince Henry of Battenberg in 1885. He later also painted a portraits King Edward VII and King George V.

Much in demand, in 1895 he produced some 200 drawings, two large paintings and two smaller paintings, but, as noted above, he did not seem to be able to budget his life style against his income.

It’s clear his work was much admired: a profile in The Regiment for Saturday 18th March 1899, accompanied by a sketch of the artist, noted Woodville’s reputation as a “battle” artist was not confined to England alone, “solely following the Army with pencil and brush”.

“Within the far-reaching chronicles of art it would be difficult to find a parallel to such rapid success,” the report noted, “a success all the more brilliant if we take into consideration the difficulties with which an English battle painter had, if he has not still, to contend. Nor is this success the less remarkable when one learns that Woodville’s art training at Dusseldorf was supervised by Von Gebhardt, a religious painter, who could make but little of his pupil, and that up to the time he was twenty he exhibited only the most ordinary qualifications for a profession which he appeared by no means eager to adopt.

“It was only when he first became connected with The Illustrated London News, during the Russo-Turkish War, that his unusual ability as a draughtsman became manifest. He made the most astonishing leaps and bounds in black and white, so much so that before a year was out, he was regarded as one of the foremost war illustrators of the day.”

Despite money troubles (or perhaps because of them), he continued to paint scenes of battle, and few battles or wars that Great Britain fought during his life were not touched upon by him, including the Second Boer War, and World War One.

The Illustrated London News commissioned him to complete a commemorative special series recreating the most famous British battles of history, including “The Charge of the Light Brigade” and “The Charge of the 21st Lancers at Omdurman”, and several “Battle of Waterloo” pictures.

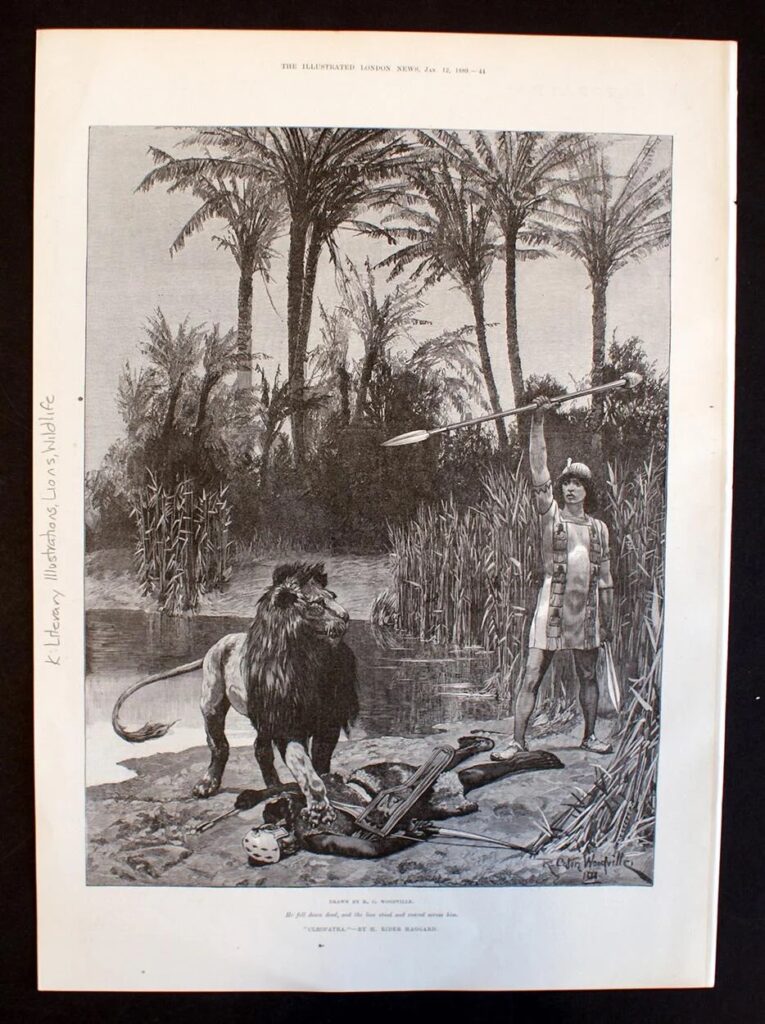

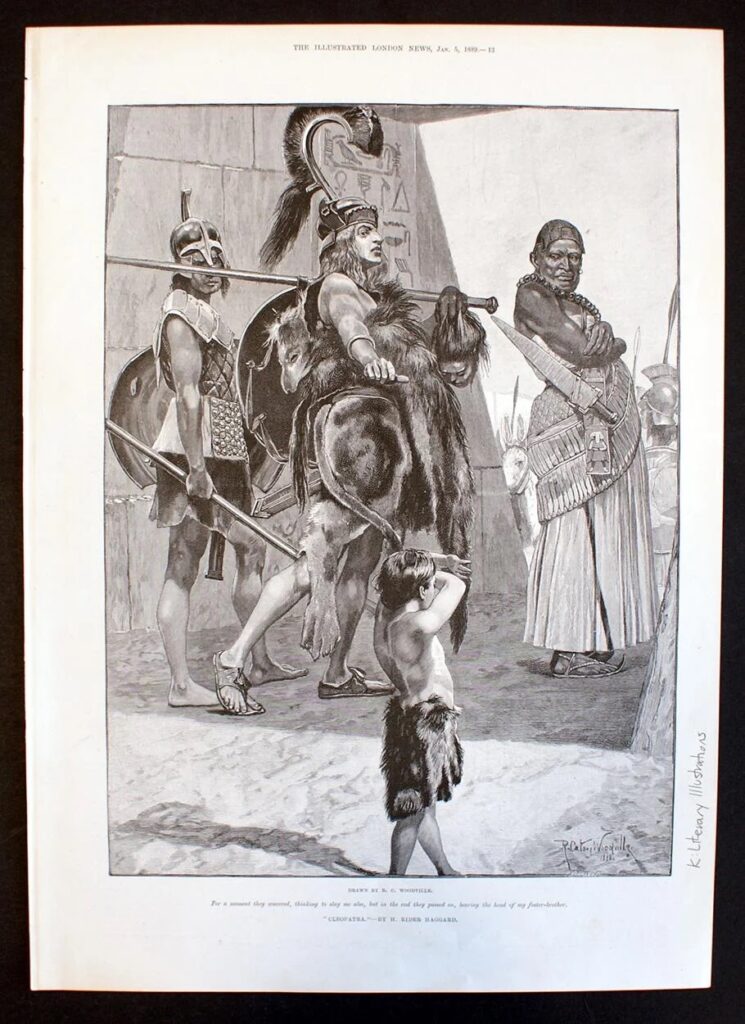

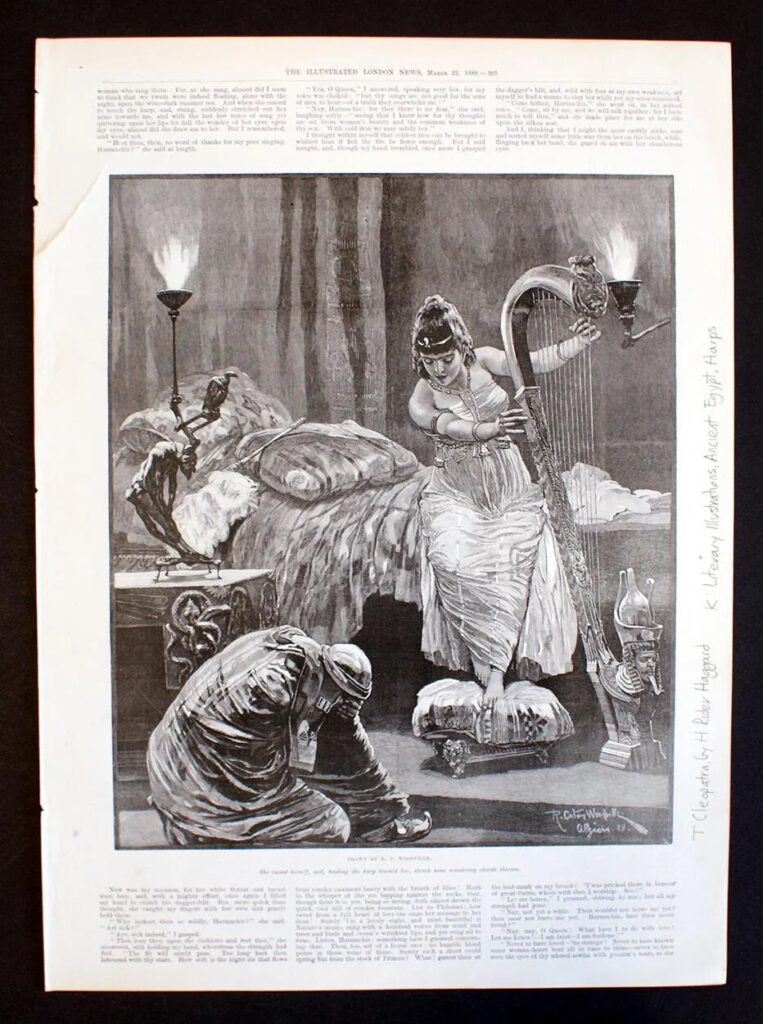

Despite his precocious talent for capturing the dramatic moments of contemporary battles, Woodville also enjoyed recreating historical scenes in both oil and watercolour.

During his lifetime, Woodville enjoyed great popularity and was considered amongst the best artists of his genre, considered at the height of his fame during the Boer War. He wrote as well as painted, and was often the subject of magazine and journal articles. He also painted several large pictures for Windsor Castle.

He had a deep passion for the British Army and joined the Berkshire Yeomanry in 1879, staying with them until 1914 when he joined the National Reserve as a captain, leaving to return to his work as an artist.

As a soldier, a report on his death in 1927 notes he served through both the Russo-Turkish campaign in 1878 and the Egyptian War, in 1882, as well as minor warlike operations in Albania and the East, and had many foreign decorations. He worked as an illustrator for the Illustrated London News during some campaigns.

During World War One, he painted works depicting contemporary events, and three of his Great War works were displayed in the Royal Academy.

The National Army Museum notes many of his World War One illustrations were reproduced as supplements to illustrated newspapers. These were detailed pictures, often printed in colour on thicker paper in order to promote sales. He focused mainly on dramatic scenes of heroism and sacrifice, which served as good propaganda for the Army.

A Tragic End

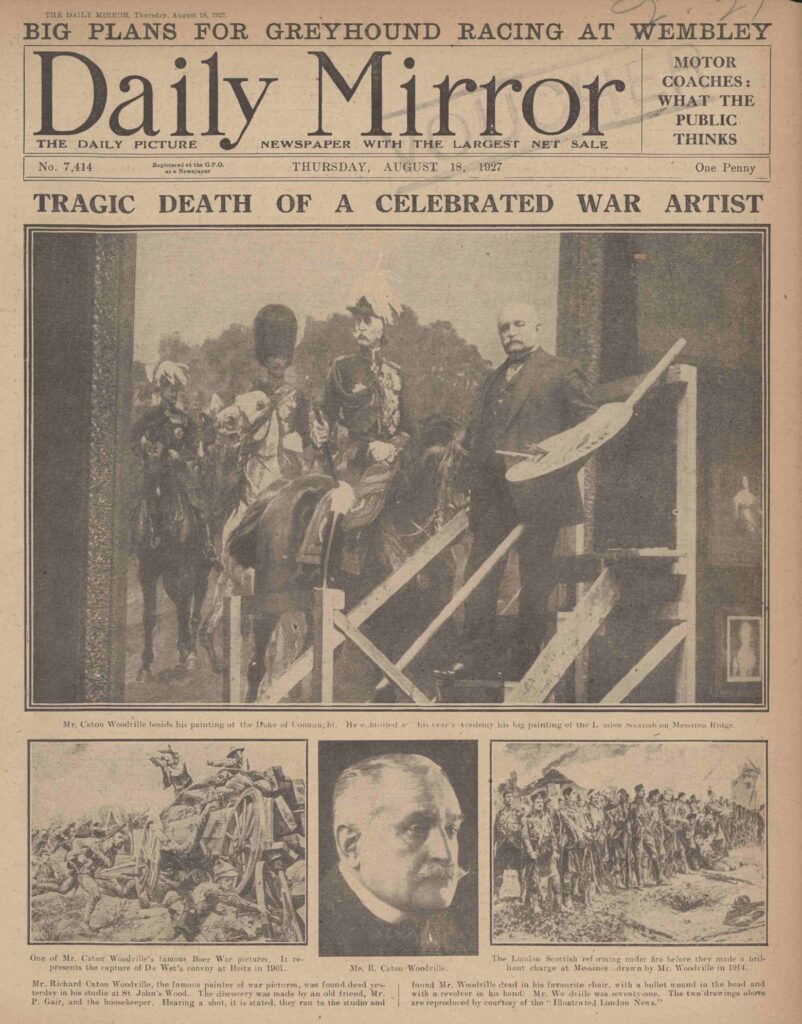

Sadly, his life ended in tragedy, committing suicide with a revolver, on 17th August 1927 in his flat in Dudley Mansions in St John’s Wood. Although discovered by his friend, Patrick Gair, still breathing, sitting in his favourite chair in his studio, he died on the way to hospital.

The Daily Mirror reported he had been happy the day before, noting his painting, “Stand of the London Scottish on Messines Ridge (now held by the London Scottish Regiment Museum Trust), had recently exhibited at the Royal Academy. But he had been suffering from heart trouble and pain from his leg, which he had broken years earlier and which had been aggravated by a second accident in Egypt. After such an active life, Woodville was worried that, at 71, already lame, that he would become an invalid.

Known by family and friends to be depressed, he was declared to have died of an “unsound mind”, his mental health probably not helped by his parlous financial state. The Evening News of 1st October 1927 notes he died near penniless an inestate, leaving just £10 in his will. His actor son, Anthony, was left to deal with his affairs, his wife having died at Christmas the previous year. (espite their separation, had also it was claimed, had affected the artist deeply).

A letter read out at an inquest on 20th August 1927, reported by the Daily Express, revealed his final,thoughts: “I am mentally and bodily ill. My health is a thing of the past. I cannot stick it any longer. I am finished, Life is sad and full of despair. It has very little strength, and to-day I say good-night.”

You might wonder, however, if his father’s death in 1905 coloured his decision to commit suicide. Like his son, he also died bankrupt, with an estimated £14,000 in debts, the end of his career marred by a “lack of demand for modern paintings”.

Whatever his reasons, his suicide was a. terrible end for a much-admired artist, whose work is still enjoyed today.

Head downthetubes for…

• Book Palace: Richard Caton Woodville Gallery

• ArtUK: Richard Caton Woodville Gallery

• Tate Gallery: Richard Caton Woodville

• Uniformology: Uniforms of the British Army by Richard Caton Woodville

• Wikipedia: Richard Caton Woodville Jr

• National Army Museum: The Charge of the Light Brigade, 1854

Detail of a coloured photogravure after Richard Caton Woodville, published by Henry Greaves and Co, London, 1895

• National Army Museum: Drawn on the Spot – War Artists and the Illustrated Press

To satisfy the Victorian public’s growing desire for authentic images of war, newspapers began sending artists to accompany British troops on campaign. The pictures they produced didn’t just complement the written words, they formed the substance of much war reporting.

All newspaper links above are from papers and magazines sourced on the subscription site, the British Newspaper Archive

Categories: Art and Illustration, downthetubes News, Features, Magazines, Other Worlds

In Memoriam: Artist Cecil Vieweg

In Memoriam: Artist Cecil Vieweg  In Review: illustrators Issue 42 headlines with Richard Corben retrospective

In Review: illustrators Issue 42 headlines with Richard Corben retrospective  In Review: illustrators 41 Limited Edition Hard Cover

In Review: illustrators 41 Limited Edition Hard Cover  The Science Fiction Art of Brian Lewis (1929-1978)

The Science Fiction Art of Brian Lewis (1929-1978)