Censorship – A Thorny Issue

Having reproduced almost all of the text from Action – The Story of a Violent Comic, it’d be churlish of us to deny the chance for people to read the final section of the introduction.

Following the section detailing the history of the ban, Martin Barker goes into some detail on the purposes of the book before addressing the issue of censorship, a subject that has permeated much of his published writings.

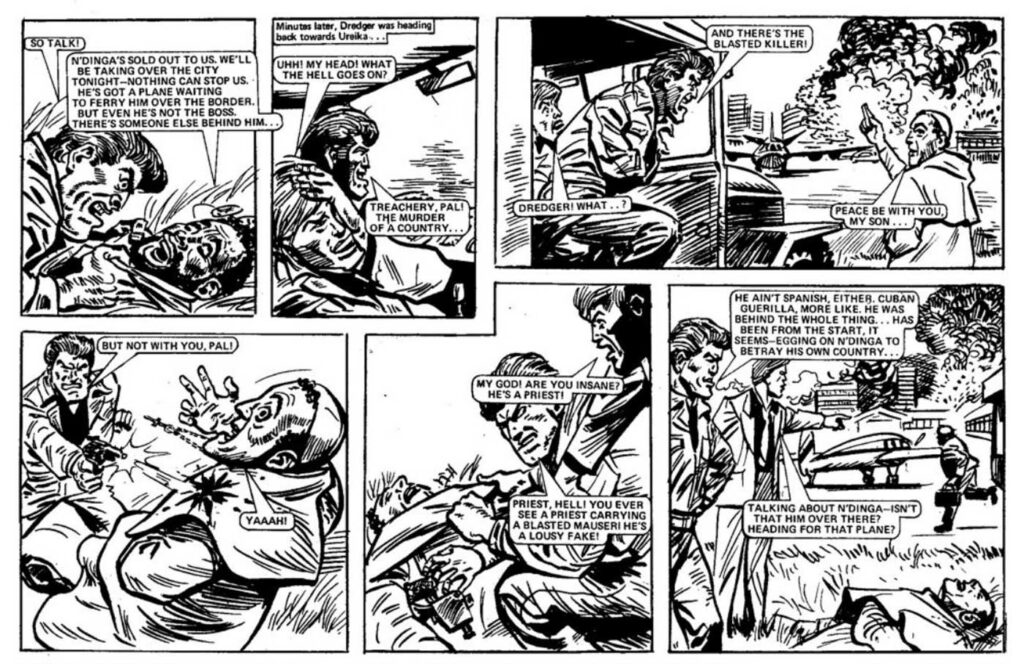

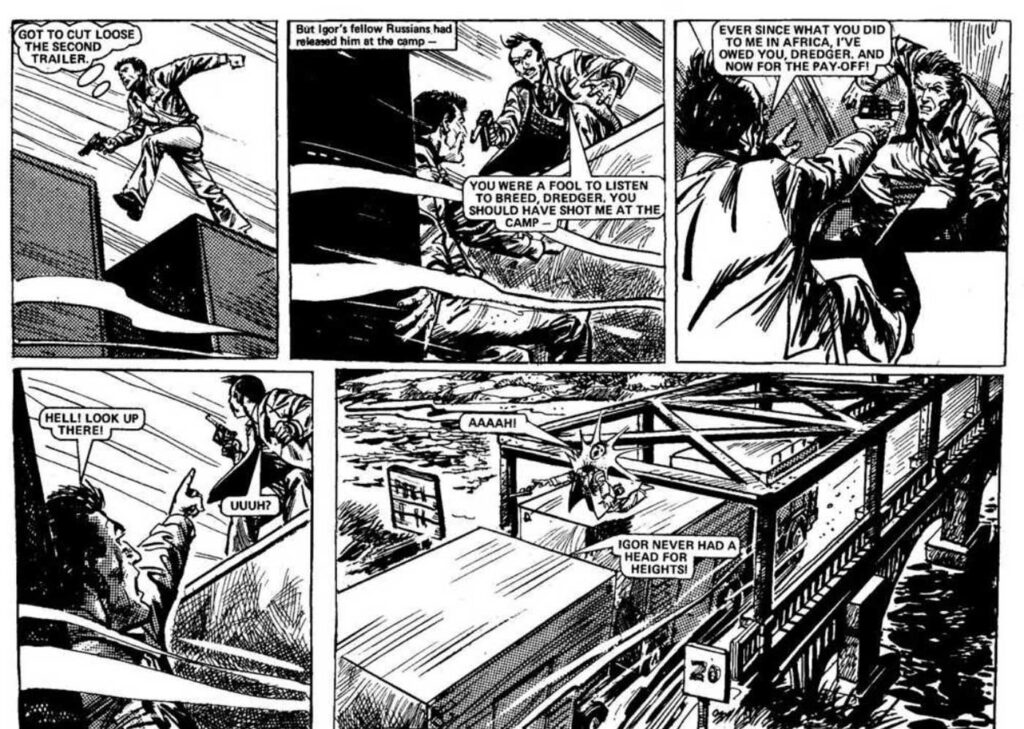

Included here the picture from “Dredger” that is mentioned by Doug Church, and not the frames of “Hell’s Highway” that everyone usually reproduces next to this comment, as a result of the wrong frames being printed in the book.

So, Should Action Have Been Censored?

There is absolutely no point in trying to make a case for Action as a hidden pot of virtues – all misunderstood sweetness and light. There is no question but that it was loved by its 180,000 readers because it was violent. The reader who wrote to me saying that what he loved was “the gore!” wasn’t atypical. The producers knew that and many of them loved it too. They weren’t above joining in the fun just for the sake of it. There is also no doubt that some of the stories were written for shock’s sake alone – though what is so terrible about that? Jack Adrian recalled in my interview the fine dividing line between those stories that were printable and those that wouldn’t make it into print:

“Some of the Dredgers I did were mainly shock for shock’s sake. One in particular comes to mind simply because the jumping off point was so bizarre (then). The image I had in mind was of Dredger shooting a priest! Never been done before. Let’s do it! So I did.

“Another Dredger is one of the few I ever had rejected in that particular market. Dredger gets attacked by savage dog at a top-secret installation. What does he do? He attacks the dog back. And instead of Dredge getting his throat torn out by said dog, he kills the dog by biting its throat out. What a twist! ‘Good God,’ said the editor, ‘Dredger killing a dog? You can’t do that. They’ll go raving mad out there.’ Which was true.”

But so what? The entire tradition of horror films turns on filmmakers deliberately building in shock-effects to thrill and surprise us, so why shouldn’t the comic-producers join in the fun? Doug Church couldn’t resist a lick of the lips when he recalled one Dredger episode where “the villain got decapitated by a bridge as he and Dredger fought on top of an express train (well actually, they tinkered with the artwork in order to get his head coming off. With it grin, he recalled himself and Pat Mills discussing where the ‘Aargh!” should seem to come from – the head, or the body. No, the issue here is whether such material can ever do ‘harm”. More than fifty years of fruitless research have been pumped into trying desperately to measure that ‘harm”. And of course, the assumption has always been that if it can be proved, that warrants censorship. Actually, there is a whole can of worms here which is rarely opened.

Exactly what are we supposed to understand by “harm”? As I said earlier, a lot of it hinges on the belief that readers are unable to help themselves, childlike creatures who are “got at” by a medium such as comics. Any influence is equated with damaging the moral capacities of these childlike readers. So let us for a moment explore these arguments. What can we say about the possible influence of Action? Can we tell if it might have done harm? In an article in the Federation of Newsagents’ magazine, their regular columnist Bob Holbrow put the standard argument perfectly:

‘In the words of Jack Taylor, World Cup referee and Wolverhampton magistrate’, reported in the Daily Mail, ‘even if stories like this affect just one child’s mind, I think they’re wrong.’ With a circulation of 180,000 and a readership of many thousands more, who is to say that only one reader of Action is likely to be adversely affected?’

It’s worth pausing over this, because we meet it so often. Holbrow, Taylor and their ilk make a series of quite absurd unjustifiable assumptions in this so-standard argument. They simply assume that there is only one possible kind of effect, So if there is a single case of a child being “adversely effected”, nothing good can be done to any of the other 179,999 readers. Somehow, these ‘experts” know in advance that the only two possibilities are that a comic like Action either has (luckily) no influence, or (worryingly) a had influence. Then, they speak with an absolute moral certainty of what good and bad influences are. Never touched by it themselves, they nonetheless know for certain that, if anyone is influenced, it is in such a simplistic way. Either (phew!) they will not be influenced at all, or (help!) they’ll copy the bad bits. All the other possible effects that one might think of are simply ignored or dismissed as irrelevant; for example, making you think, or giving resources to the imagination, filling up boring time, or providing a private space away from adults, dramatising how you feel about the world, giving a sense of belonging to a special community, or just giving you the pleasure of reading, add your own. The list could be endless, The people who can’t or won’t see that are the idiots who moralise about comics, films, TV and have the power to get politicians’ and media attention in inverse proportion to their numbers.

In fact, modern studies of the media have long since left behind such stupidities. Instead, researchers will ask questions such as: what part does this comic play in its readers’ lives? How does it fit in with their routines, with their social relations’? How do they use it and relate to it? My own research on Action readers came up with some real surprises. More than a hundred former readers of Action all over the country filled in a questionnaire for me. These threw up a striking difference between those who were fans of Action and those who read it less committedly. The fans saw the politics of the comic. They saw it as their friend in a world that was cruel, friendless and held no hopes for them. Most interestingly, a number of them said it fitted for them with the motivations behind the punk movement of the mid-seventies. Action’s rudeness, its dismissal of authority and its portrayal of life as a battle for survival, all contributed to this. These readers found the comic intelligent, thoughtful. “it wade me think,” said one committed reader another wrote to me that “the idea that the heroes were not always good guys and did not always win helped destroy the black and white image I had learned. (Now how do you class that’? Was that an “adverse effect’?) The casual readers were the ones who worried about being taken over by the comic. They thought the comic was unintelligent, appealed to the basic instincts in them – and therefore dismissed it.

What I am suggesting is this; the more involved the readers were with Action, the more complicated the effects on them – and the more they saw a point and a meaning to the stories. They related to them as dramas which made them think about their world. My evidence confirms that we just can’t look at Action in the naive terms the critics have again and again tried to impose, We can ask: Did it affect them? How much? Was ‘even one boy’ influenced into doing an evil deed by his reading of it’?” The more readers got hooked on Action, the more complicated and interactive was their relationship with it.

So where does this leave the arguments over whether the comic should have been allowed to continue’? Arguments over censorship are long and tricky, and in my opinion not usually all that interesting. The plain fact that ought to be acknowledged about any comic is that censorship of many kinds is a daily fact of life. Someone in a company – big or small, makes the difference, decides a comic will be produced. To produce it, they need some stories, First stage of “censorship”: accept some story ideas, reject others. Second stage of “censorship”: select some writers, reject others (for style, experience, characterisation as well as for other qualities like – what are they like to deal with, will they deliver on time?). OK, they start writing, and send in some scripts. Third stage of “censorship”: the editors check each script for its fit in the comic, for pace of story, for development of the characters, etc (as well as for legality and the like). They also check whether the artist will be able to realise it. etc. Then they send it on to their chosen artist (and that’s a fourth stage of “censorship”). Now the artist comprises the fifth stage – how will s/he interpret the script’? Will s/he stamp a style on it, how much will s/he interpret/deviate from instructions? Back goes the artwork for stage six: the sub editors work it over, for fit into the comic, any problems they see in it. Now the comic is put together with editorial material (all of which has been vetted several times over). Next, the entire mock-up is debugged for problems – and goes to the printers (who do themselves sometimes attempt their own stage of censorship, for example from fear of legal consequences). None of these is a purely technical process. All these stages involve decisions about what is a good story, what is the best way to do it, what is acceptable or not.

So which stages do we object to as “censorship”’? Surely it isn’t a question of whether there is censorship – perhaps that is no longer a very helpful word – but why, for what purpose, and by what criteria it is done. Let me end this…with a personal comment on may own views on this. There will always be editorial decisions, which from someone else’s perspective, look like censorship. There just isn’t a way round that. I believe that writers, artists and audiences have a right to object:

- when the rules behind those decisions are kept secret;

- when they are based on pressures from those who have no interest in the medium of comics, only in enforcing their own views of what comics should be allowed to deal with;

- when they are based on ‘fear of the visual’, that is, the fear that drawing a picture of something is likely to stimulate someone else to try to make that picture come alive;

- when they are premised on wholly unsupportable ideas about how readers might be influenced, and when those readers are by the nature of things, debarred from defending the comic they’ve chosen to buy and read.

On all those grounds, the campaign against Action was wrong and, I believe, positively dangerous. But Action throws up one even more important issue about censorship. Examine the evidence I give in the book concerning the changes which were made when the comic was given editorial reconsideration. Compare those changes with the rhetoric of the campaign against it. They don’t match, do they? That is because – and I believe it can be shown that this often happens – the demands for censorship in the name of protecting vulnerable children were in fact disguised political objections. Action may not have been a momentous piece of our culture, which will still be recalled in a hundred years, but my evidence shows that for a sizeable group of people it made a difference to their world. And just because the comic was violent doesn’t mean it made their world more violent. Rather, it gave them means for thinking about the grubby, violent, cynical world they were born into. Who gave anyone the right to take that away from them?

Read More in this Section of “Sevenpenny Nightmare”

The Excerpts: Action: The Story of a Violent Comic (about the book by Martin Barker) | Action: The Story of a Violent Comic – Introduction | Developing the Formula | The Critics Bite Back | Moving in for the Kill | So, Should Action Have Been Censored? | Action: The Story of a Violent Comic – Reader Survey | Hook Jaw: The Shark Bites Back | The Lost Pages of Hook Jaw – TO BE ADDED | How Lefty Lost His Bottle – TO BE ADDED | The Lost Pages of Lefty – TO BE ADDED | Death Game 1999: Steel Balls to the Finish | The Lost Pages of Death Game 1999 – TO BE ADDED | When The Crumblies Flipped It: Kids Rule OK…? | The Lost Pages of Kids Rule O.K. | Dredger… No Comment | The Final Reckoning | Estimating Action

Sevenpenny Nightmare Section Index

This is an excerpt from Action: The History of a Violent Comic by Martin Barker, featured here as part of the Sevenpenny Nightmare project edited by Moose Harris. Text © Martin Barker.

ACTION™ REBELLION PUBLISHING LTD, COPYRIGHT © REBELLION PUBLISHING LTD, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

See this section’s Acknowledgments section for more information