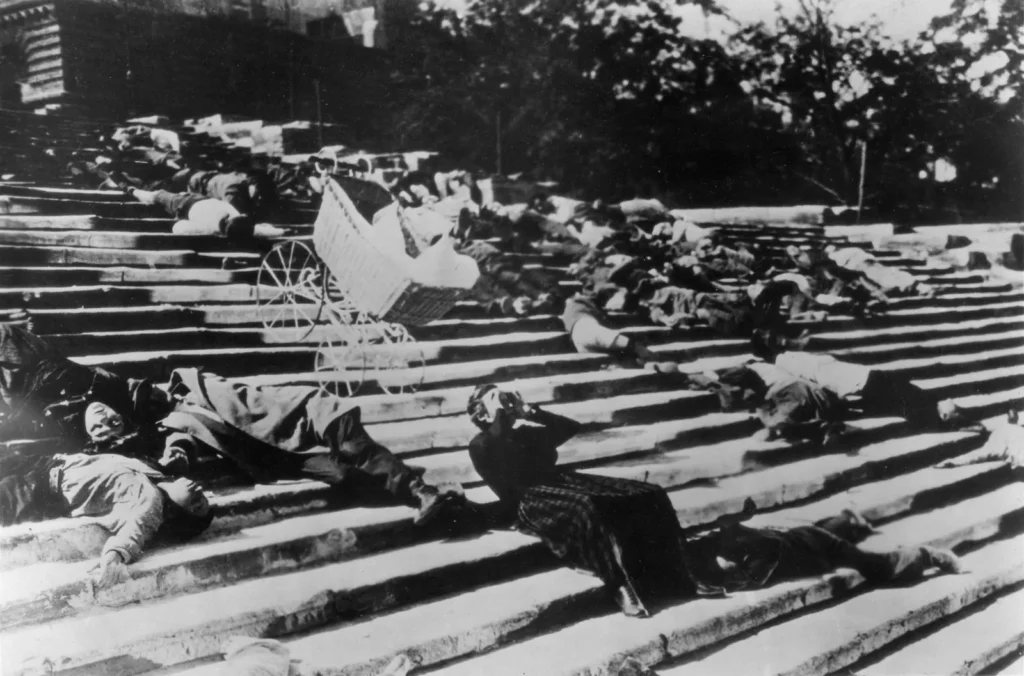

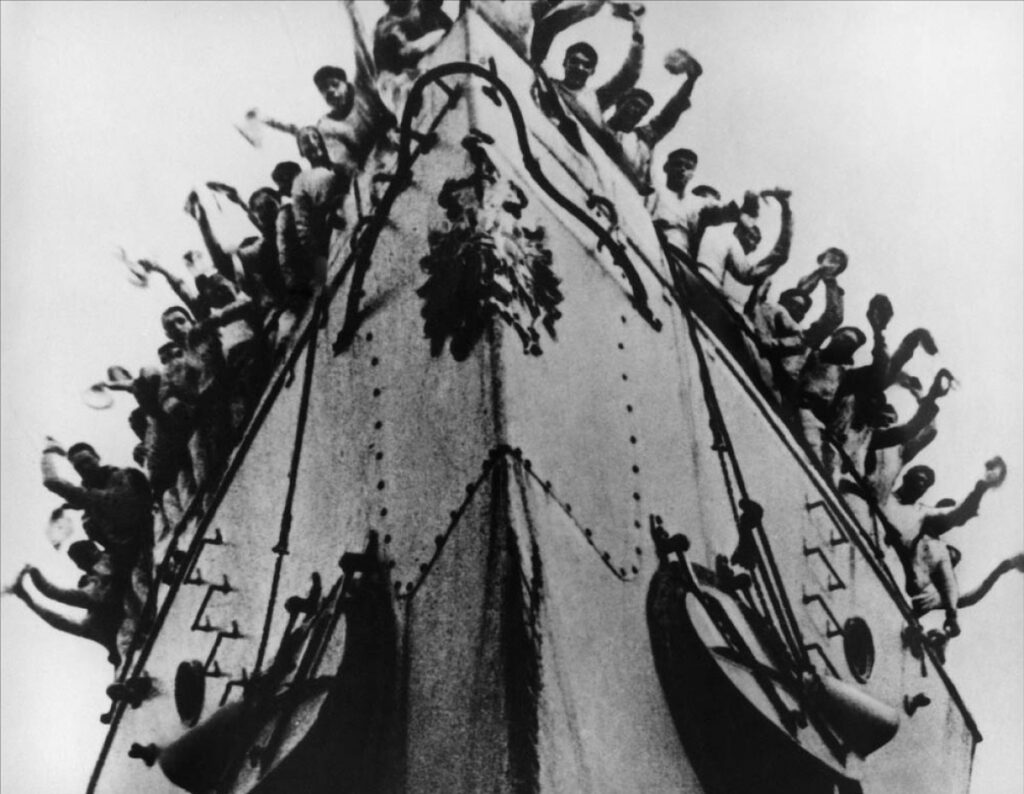

A fixture in the critical canon almost since its premiere, Eisenstein’s film about a 1905 naval mutiny was revolutionary in both form and content. Battleship Potemkin is renowned for its dynamic compositional strength and editing of such frame-perfect precision that it’s hard not to be swept along. The set-piece massacre on the Odessa Steps still packs a sledgehammer punch.

(Some links below are AmazonUK Affiliates)

Review by Tim Robins

September 2025 saw the 100th anniversary of Serge Eisenstein‘s Battleship Potemkin (1925), still regarded as one of the greatest films ever made.

Critic Roger Ebert once wrote that Battleship Potemkin is so famous that it is no longer possible to come to the film with fresh eyes. Maybe so, but, thanks to a new soundtrack by the Pet Shop Boys, it is possible to come to the film with fresh ears.

The new score, composed by the group working with the Dresdner Sinfoniker, originally debuted live in London’s Trafalgar Square on 12th September 2004 to an estimated audience of 25,000 people, performed with the Dresdner Sinfoniker and orchestrated by Torsten Rasch, before going on tour internationally.

The BFI have released a new, Region 2, BluRay combining their soundtrack with a newly remastered, digital, version of the film. The film and score enjoyed a limited release in theatres and are now available on BluRay, CD and new vinyl pressing from Parlophone.

The Extras are not all about the Pet Shop Boys, but they are about their score, including a (very) short, impressionistic, presentation about crowds gathering for the Trafalgar Square event and a 68-minute documentary 2017, Hochhaus Sinfonie (“Skyscraper Symphony”) about a 2006 performance, this time in the Dresdner Sinfoniker’s native city of Dresden.

The event was staged in a Russian housing block and the documentary focuses on interviews with former residents who share their memories of life behind the Iron Curtain. The Pet Shop Boys Neil Tennant suggests that Battleship Potemkin can be understood as a response to oppression of all kinds.

The apparently absurd juxtaposition of Pet Shop Boys’ synth-pop with Eisenstein’s famous work piqued my interest enough to see the film at my local art house cinema (The Duke of York’s, Brighton). Post film, it has been fascinating to revisit the way the director reworked events around the revolution, by using Soviet aesthetics, (including, famously, the technique of montage editing).

In The Battleship Potemkin: The Film Companion (2000), Richard Taylor, concludes that while a broader public thinks Star Wars (1977) and Titanic (1998) “are two of the greatest films ever made”, Eisenstein’s remains, at best, “a name to conjure with, at worst a completely unknown quantity.”

I’m not sure about that. Certainly, Act IV’s Odessa Steps sequence, in which the Tsar’s Cossack troops relentlessly shooting and trampling citizens underfoot (including a baby in a pram toppling down the city’s steps), is widely taught on film and media studies courses and has been repeatedly referenced by other media.

Nods to the Odessa Steps sequence can be found in Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985), which sees rebels fleeing down the steps of the Ministry with a grotesque, vacuum cleaner standing in for the pram and in Brian De Palma’s The Untouchables (1987) includes the pram and the baby in a shootout between Elliot Ness and Al Capone’s henchmen on the steps of Chicago’s Union Station.

On television, the Doctor Who story, The Invasion (1968), includes an Odessa Steps inspired sequence of Cybermen march down steps leading from St Paul’s cathedral and mowing down members of the public. Granada TV’s dramatisation of the Sherlock Holmes story “The Golden Pinc-Nez”, adapted for television by writer Gary Hopkins and director Peter Hammond, focuses on a single moment in which a school mistress is shot in her eye.

One way or another, Eisenstein’s film has helped establish Battleship Potemkin’s place in film history and popular memory, as it was intended from the start.

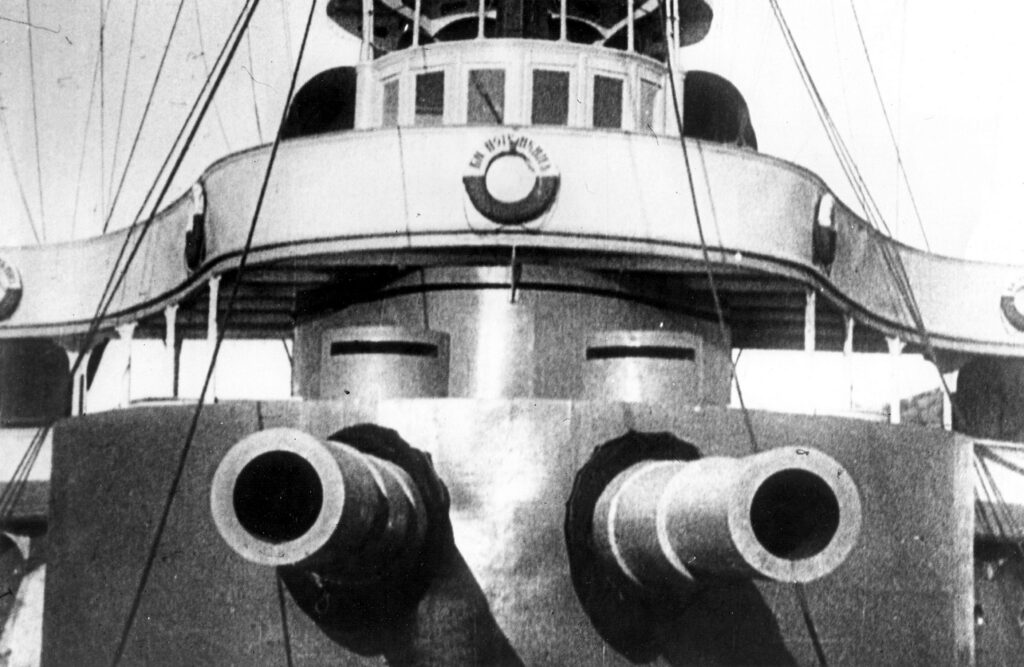

The film was commissioned to commemorate The Russian Revolution of 1905. Across Five Acts, it tells of a mutiny on board The Potemkin which saw the ship’s crew turn against the ship’s officer class, press the battleship into support for the Russian Revolution and confront the Tsar’s formidable fleet of warships sent to destroy them.

When released in Moscow, Battleship Potemkin found itself up against the silent adventure film, the million dollar Hollywood blockbuster Douglas Fairbanks in Robin Hood. Eisenstein’s masterpiece may have lost that particular skirmish, but, over time, it gained ground, growing in popularity and critical acclaim.

Eisenstein’s approach to cinema was partly informed by the experiments of Ivan Pavlov, who saw how dogs could be conditioned to salivate at the ring of a bell. Eisenstein saw Battleship Potemkin as a powerful stimulus designed to elicit feelings of comradeship, and even a revolutionary spirit in its audience. Of course audiences aren’t dogs, but they might as well have been in the eyes of governments and the film went on to be censored because of its socialist, revolutionary messaging.

The 29th April 1926 version, screened at the Apollo Theater, Berlin, under the auspices of Prometheus Films, was heavily censored under pressure from the Weimar authorities. It was this censored version that became the basis copies sent to America and England. There, the copies were further censored.

The British government feared the film’s revolutionary message, particularly in the context of rising left-wing activism and the 1926 General Strike. The BBFC denied the film a certificate for its “inflammatory subtitles and Bolshevist Propaganda”.

Battleship Potemkin was denied certification for longer than any other film in British history and was not officially approved until 1954, after the death of Stalin.

The BluRay is classified as PG. The BBFC’s content advice points to the Odessa Steps sequence, describing it as “a prolonged sequence” during which, “a large crowd of civilians is massacred by soldiers who open fire on them and slash swords in undetailed fashion”. The BBFC also advise that the film includes “occasional smoking in a historical context.”

In the past, Eisentien’s film was cut as much for its perceived violence as its political messaging. Montage editing can be brutal as demonstrated in a scene in which a schoolmistress is shot in the eye. Eisenstein described the scene as an example of ‘logical montage’.

The director’s notes read, “Woman with pince-nez. Followed immediately – without a transition – by the same woman with shattered pince-nez and bleeding eye. Sensation of a shot hitting the eye”. In other words, we infer cause and effect, rather than actually seeing a bullet leave the barrel of the gun and enter the woman’s eye.

Outside of cinema’s mainstream, montage went on to inform Diziga Vertov’s Modernist documentary Man with A Movie Camera (1929) and that classic of surrealism, Un Chien Andalou, (1929) by director Louis Buñuel and Salvidor Dali. The film’s shots – infamously, an open blade cutting across an eye juxtaposed with a cloud cutting across the moon – are used to evoke a disturbing dreamscape torn from the unconscious.

A probably better known use of “logical montage” is Psycho’s (1960) shower scene. During a brutal stabbing, we are led to think that we see the serial killer’s knife enter their victim’s body. But this “violent sensation” is inferred from intercutting shots of a raised knife,the victim screaming, a shower curtain being torn and, finally, a swirl of blood disappearing down a plughole intercut with the victim’s dead eye.

The shower scenes’ rapid editing – 52 cuts occupying 45 seconds of screen time – was executed by editor George Tomasini, guided by Hitchcock’s eye for sadism and the precise storyboard-direction of Saul Bass. Of course, the scene is also a tour de force from actress Janet Leigh (as Crane), her body double, Marli Renfro, and Margo Epper (doubling for the killer). The scene also benefits from the shrill, stabby music of Bernard Herriman. Was the final shot of the victim’s eye a homage to the shot-in-the-eye-death of the School Mistress in The Battleship Potemkin? Probably not.

Of course, Eisenstein’s film is more than the sum of its editing techniques. His Eisenstein’s “blocking” of scenes is more than equal to any movie today. A shot of sailors resting in a web of hammocks is strikingly stylised, while also foreshadowing the death of Muntaneer Grigory Nikitich Vakulenchuk, (Aleksander Antonov), whose lifeless body falls from the deck and is suspended above the sea by the ship’s rigging.

Near the film’s climax, a group of sailors emerge from the shadows of the engine room and stare down the Tsar’s oncoming fleet. It’s as if the sailors themselves are part of the machinery of war. Many shots of shirtless sailors , below deck, are unintentionally homoerotic. Together, the sailors’ faces and torsos create a sweaty brotherhood of the body.

Within the conventions of Soviet aesthetics, we are supposed to see characters as ‘types’, ‘class actors’ and symbols of wider ideals. That’s no baby in a pram, that’s the innocence of the Tsar’s victims and the fragile spirit of the new, on just having been born. But the performers, their faces shot up close and personal, still have the force of individualism stamped upon them. I came away from the film feeling I had personally spent time with Soviet Citizens. Trotsky himself, writing a critique of the Futurist movement, argued that prioritising the ‘objective’ over subjective

consciousness betrayed, “a very inadequate understanding of the dialectic nature of the contradiction between individualism and collectivism”.

When Battleship Potemkin first opened, the film began with an on-screen quote from Trotsky: “The spirit of mutiny swept the land. A tremendous, mysterious process was taking place in countless hearts: the individual personality became dissolved in the mass, and the mass itself became dissolved in the revolutionary élan.”

In 1934, Trotsky’s words were removed by Soviet censors and replaced by a quote from Vladimir Lenin’s Revolutionary Days (1904). It read, “Revolution is war. Of all the wars known in history, it is the only lawful, rightful, just and truly great war… In Russia this war has been declared and won.”

Some film critics have not been impressed by the film’s propagandistic messaging. Pauline Kael, film critic for the New Yorker from 1968 to 1991, the film could be appreciated for its freshness and excitement “ even if you resist its cartoon message.” The critic extended her critique to the film’s form and content, writing that our familiarity with film techniques used in The Battleship Potemkin make the film seem like “a technically brilliant but simplistic cartoon.”

Kael’s review is often described as ‘positive’, but her evaluation is equivocal. Her verdict is that, while undoubtedly great, “it’s not really a likeable film.” Frankly I think “awesome” is a better description than “unlikeable”.

Even if we accept Kael’s views often “defied the consensus of her contemporaries”, her judgment, that Citizen Kane deserved the title of “The Best Film Ever Made ”, was entirely typical of her film critic kind. And, in any case, The Battleship Potemkin was intended to evoke the spirit of revolution, not the refined sensibilities of The New Yorker and its readers.

Of course there are misfires in the film. There are a couple of model shots of the battleship floating in a water tank that I doubt passed muster even back in the day. And Eisenstein’s symbolism can be laboured. Shots of sailors fuming, mutinously, below decks are intercut with a pot of rancid soup being brought to the boil. The sequence seems terribly on-the nose and protracted, but it still had an effect. I began simmering with impatience.

From the start, everything about Eisenstein’s film was challenging. That included its orchestration. When the film was to open in the Bolshoi Theatre, the orchestra went on strike, demanding to know what sort of music was appropriate to accompany the film’s scenes of maggots and rotting meat.

The most acclaimed score was composed by Edmund Meisel and premiered at the Apollo theatre. The music helped make the film a sellout success and was the composer’s big break into the German film score industry. Perhaps recalling the difficulties of illustrative music, Eisenstein requested that, during the final reel, in which The Potemkin confronts the combined mass of the Tsar’s navy, the music “should be rhythm, rhythm and, before all else, rhythm.”

Visiting Berlin, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford asked for a private screening. Fairbanks declared Eisenstein’s film to be “one of the most intense and profound experiences of my life”. He was so impressed by Meisel‘s score that, supposedly, he invited the composer to Hollywood.

Meisel’s innovative work has gone on to be hailed as one of the “greatest scores of the twentieth century”.

I am not sure Pet Shop Boys’ score is destined for similar greatness. In fact, I was surprised by their involvement, but that was my ignorance of the group’s artistic and political interests. For example, the Boy’s 1980s hit, “West End Girls”, includes the lyric “From Lake Geneva to the Finland Station” – a reference to the train route taken by Lenin when he was smuggled into Russia during World War One and may have been inspired by the title of Edward Wilson’s book, To the Finland Station (1940), a sweeping history of revolutionary thought and action from The French Revolution to Lenin’s arrival, in 1917, at the eponymous station.

The most successful part of the new score is in giving the Dresdner Sinfoniker greater play. They add a fullness to the score. The final act was pretty cacophonous. It feels as if the group’s crashing, relentless score wants to carry the storytelling all by itself.

Fortunately, the film remains more than a match for the Boy’s synth-pop-impertenance. It’s as if Eisenstein himself shouts “Hold my Vodka!” (not an actual intertitle card, by the way). In the theatre, I felt the volume had been turned up well beyond 11.

So, while those who have eyes to see will enjoy the remastered film, those who have ears to hear may want to wear earplugs or turn down the volume on their television sets.

Meisel’s score can still be found on DVD and BluRay.

I know aficionados are waiting for a 4K release of the film with a choice of soundtracks, but I don’t regret taking the opportunity to see this audacious pairing of pop and popular memory.

Tim Robins

• The Battleship Potemkin / Pet Shop Boys Score (Limited Edition Blu-ray & CD) can be ordered direct from the BFI here | AmazonUK Affiliate Link

• CD and vinyl pressing from Parlophone (AmazonUK Affiliate Link)

Title: BATTLESHIP POTEMKIN / PET SHOP BOYS (BLU-RAY & CD)

Director: Sergei Eisenstein

A fixture in the critical canon almost since its premiere, Sergei Eisenstein’s legendary film about a 1905 naval mutiny was revolutionary in both form and content. Battleship Potemkin is celebrated for its dynamic compositional strength and editing of such frame-perfect precision that it’s hard not to be swept along. Despite endless quotation and parody, the set-piece massacre on the Odessa Steps still packs a sledgehammer punch.

Extras

- Hochhaussinfonie (2017, 68 mins): as the Dresdner Sinfoniker and Pet Shop Boys prepare for a unique musical production, utilising a prefabricated building in what was once East Germany, this documentary explores not only the complexities of the concert, but also the residents and their lived experiences of a very different time

- Trafalgar Square highlights (2004, 4 mins): an impressionistic short film capturing the build-up and performance as Pet Shop Boys premiered their newly composed score for Battleship Potemkin with the Dresdner Sinfoniker in London

- CD featuring the score by Pet Shop Boys and Dresdner Sinfoniker

- Trailer (2025)

- LIMITED EDITION Illustrated booklet featuring new writing by Chris Heath and Sarah Cleary, and archive pieces by Neil Tennant and Michael Brooke

Upcoming Screenings

This version of Battleship Potemkin has been screened in various cinemas across the UK. Upcoming dates include:

From 13th October 2025

From 26th October 2025

Light Cinema Addlestone

Light Cinema Banbury

Light Cinema Bolton

Light Cinema Bradford

Light Cinema Cambridge

Light Cinema Huddersfield

Light Cinema New Brighton

Light Cinema Redhill

Light Cinema Sheffield

Light Cinema Sittingbourne

Light Cinema Stockport

Light Cinema Thetford

Light Cinema Walsall

Light Cinema Wisbech

Head downthetubes for…

• Wikipedia: Sergei Eisenstein

• The Russian Archives: Sergei Eisenstein – The Art & Science of Cinema

Sergei Eisenstein (1898–1948) is regarded as one of the world’s most creative, pioneering, and influential filmmakers and is among the most lauded figures in Russia’s cultural history. From Strike (1925) to Ivan the Terrible: Parts I and II (1944–46), Eisenstein’s films, as well as his writings and his theory of montage, have shaped how cinema is made and understood. Seen today, films like Battleship Potemkin, October (also known as Ten Days That Shook the World), and Alexander Nevsky still shock with their extraordinary beauty and invention.

• Sage Journals: The revolution will be dramatised

Filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein manipulated the past in his work, but was it for dramatic or propaganda purposes? The director is often portrayed as the godfather of propaganda in film. David Aaronovitch argues that historical drama can also be manipulative when it ignores the past

• Luddite Robot: Battleship Potemkin, Propoganda in Action

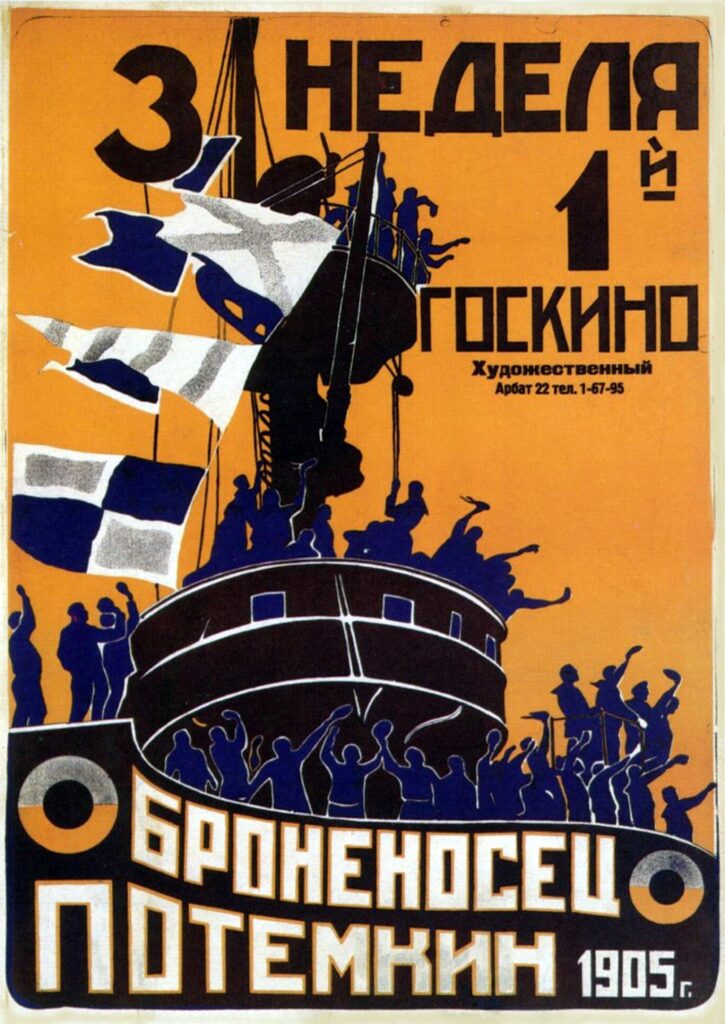

• MoMa: Aleksandr Rodchenko (1891–1956)

Alexander Rodchenko designed posters for Sergei Eisenstein’s film Battleship Potemkin and was commissioned to design the Soviet pavilion to the world exhibition in Paris in 1925. The experimental and innovative “new vision” was celebrated across Europe.

• Pet Shop Boys – Official Site

• Dresden sinfoniker – Official Site

Categories: Audio, Digital Media, Features, Film, Other Worlds, Reviews