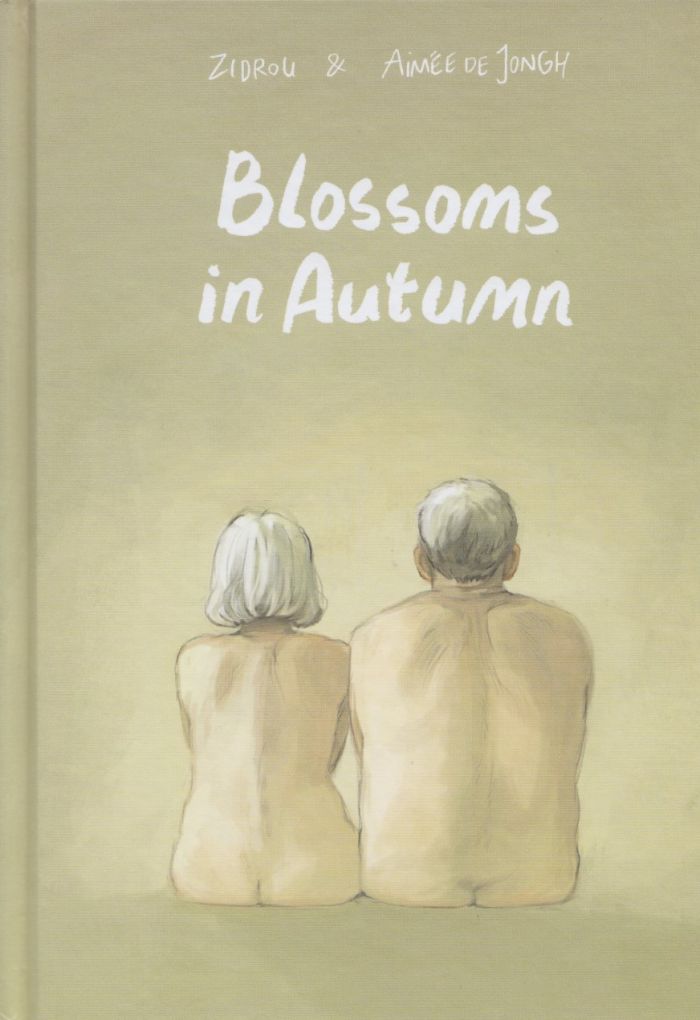

Blossoms in Autumn

By Zidrou, Aimée de Jongh

Translated by Matt Madden

Published by SelfMadeHero

Blossoms in Autumn, a collaboration between Belgian writer Zidrou and Dutch creator Aimée de Jongh, touches on a subject we don’t see all too often – love in later life.

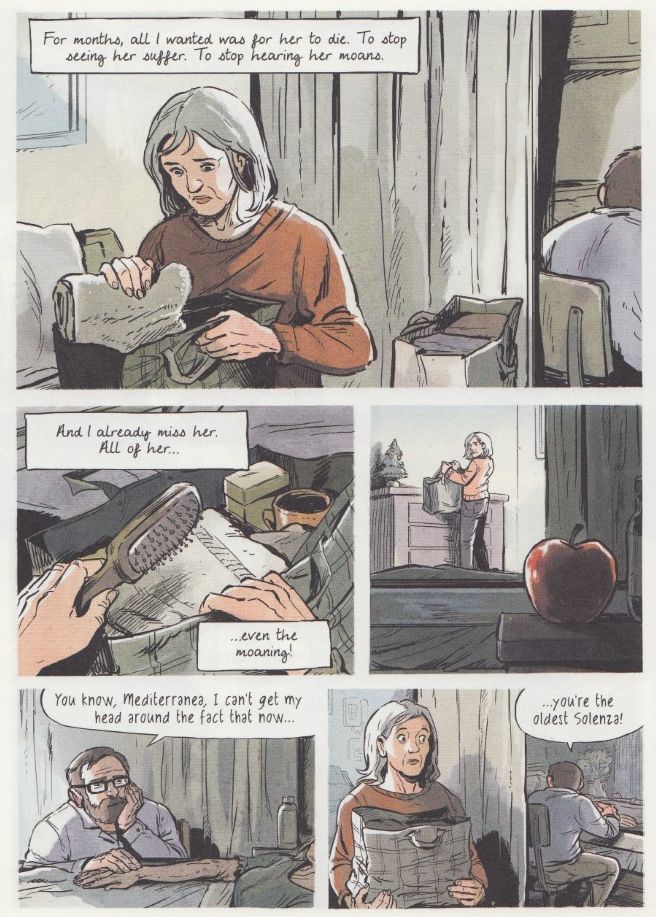

We open with Mediterranea, a lady of mature years, dealing with something that sadly we all have to as we get older – losing loved ones to old age. She’s by her mother’s bedside as she passes, and within just a few pages the deeply emotional tone of Blossoms in Autumn is very apparent. Despite having just met this character and being introduced to her world I found myself very moved, my empathy stirred.

It has been a slow decline over months before her mother breathed her last breath, and as anyone who has seen a loved family member fighting the inevitable will know, this unleashes a strange mix of emotions – your desire to have them continue to live battling with the feeling that this only leads to prolonged suffering, it is better for them if they just went now (and the guilt for thinking that way) – that pushes you into a bizarre feeling of unreality and disconnection from the everyday world around you.

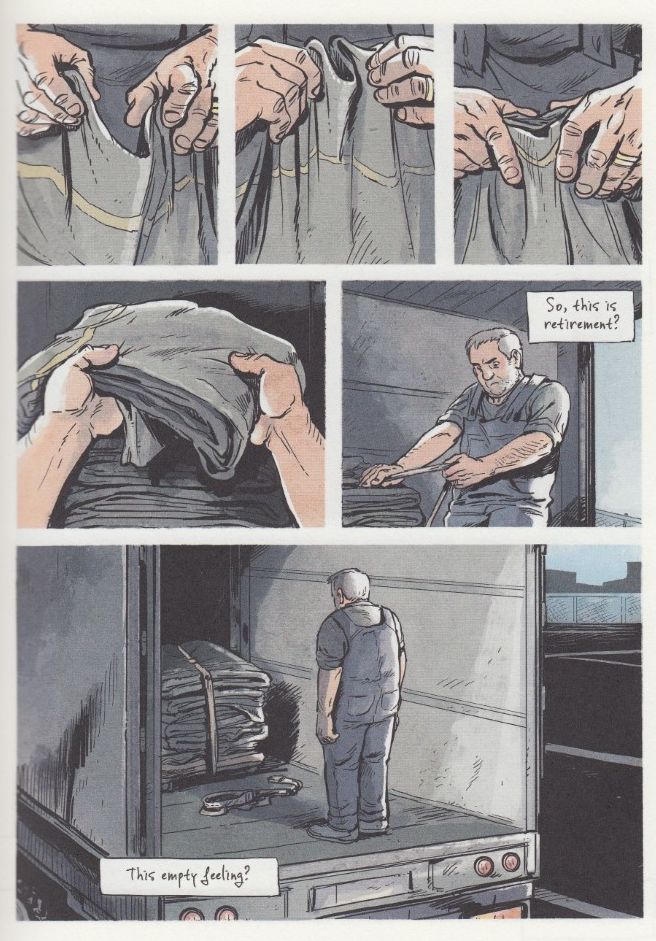

“So this is retirement? This empty feeling...”

This scene cuts to Ulysses, a removal truck driver, carefully tidying his van for the last time. The firm he has worked for over decades is downsizing, and he has been given early retirement. For some this might be a gift, more time to enjoy life after work, but his wife Penelope (yes, Ulysses and Penelope, he has heard all the jokes) passed away some years before. Of their two children only one remains, a doctor, married but with no children of his own, so Ulysses doesn’t even have the option of playing doting grandfather to any grand-kids in his old age.

Faced with an empty home and a forced retirement that isn’t his choice, he too is facing a moment of unwanted change, perhaps not quite the same as Mediterranea’s loss of her mother, but still a huge, emotional wrench, bringing with it a form of loss and grief too, and that questioning of how you came to this place in your life.

“Some word have a bite to them. They dart out from the middle of a sentence, like a viper from under a rock… and sink their fangs into your ankle a little deeper with every syllable.”

Mediterranea, still dazed from her mother’s passing, leaves the hospital to take the bus home, her brother’s words about her now being the oldest member of the family echoing in her head along with thoughts of her own age and mortality. De Jongh’s art perfectly captures that wretched dislocation you feel during grief, of trying to do something as mundane and everyday as get on the bus but your mind and spirit are a million miles from the body that goes through these routines, part of you almost unable to take in the fact that the regular world is still going on, the planet still turns, buses still run, people are getting on and off with their own lives to run, oblivious to the emotional bombshell which has just shattered you inside, while outside you still go through all the normal motions.

Aimée similarly crafts some beautifully-drawn scenes with Ulysses, trying to fill his now long, empty, lonely days. Sure there are little fun moments, like hanging with a regular group of fellow supporters of his small (and not very good) football team, cheering and booing, their faces going from triumph to anguish, the post-match drink and talk of how much better it was back in the day. But those are the exceptions and stand in contrast to most of his time, alone at home, or walking by himself in the park. The latter is subtly handled, the expressions and body language she gives to Ulysses passing two other older men chatting amiably on a park bench (why doesn’t he talk to people like that, join in?) or seeing parents playing with young children in the park speaking volumes.

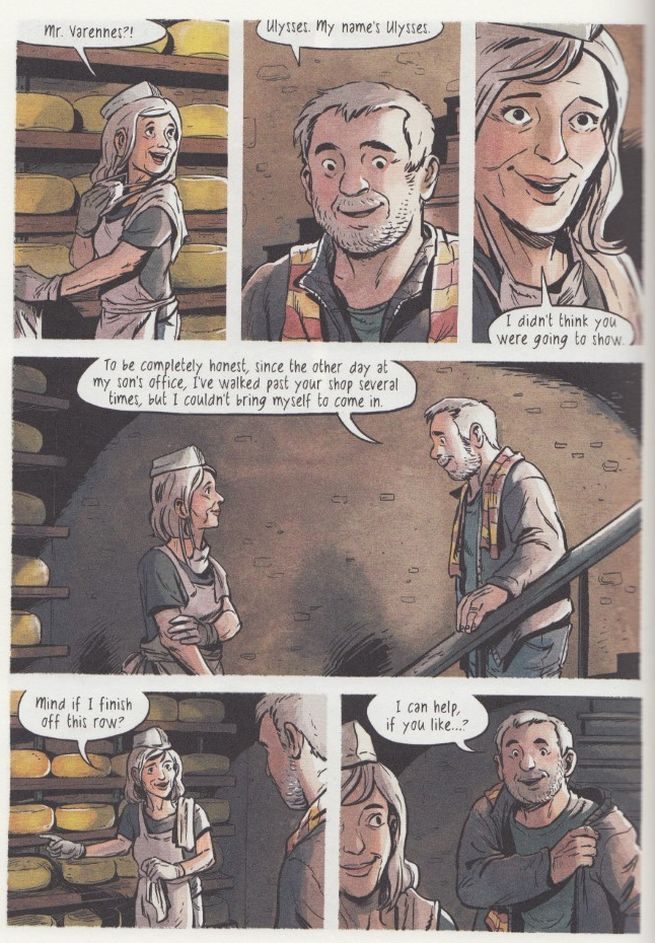

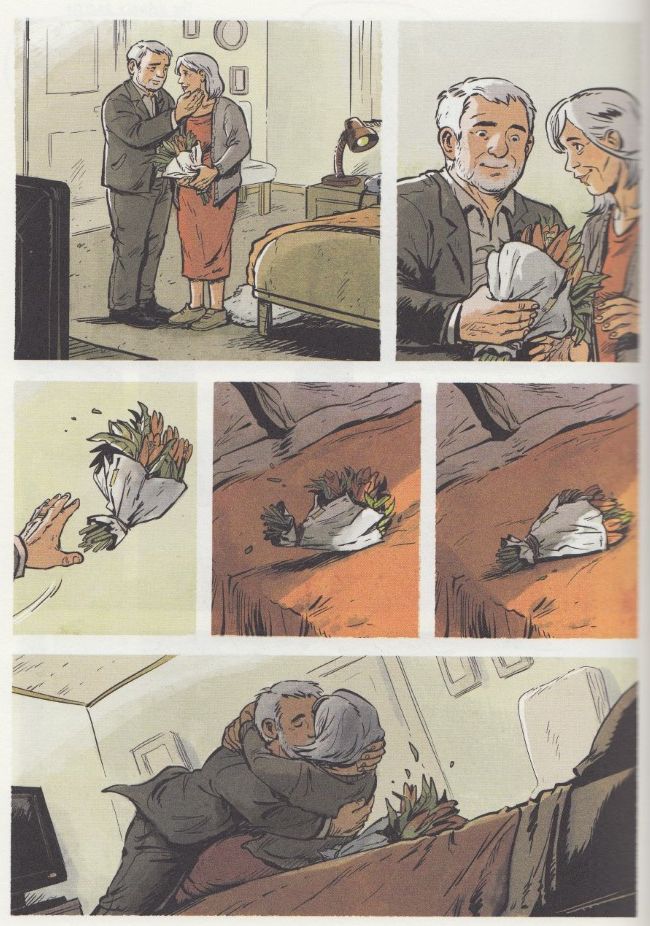

Their paths cross in the waiting room of the local doctor’s office (his son’s office, in fact), and these two drifting souls start to chat, in the way you sometimes do to strangers, which leads Ulysses to decide he has nothing to lose and follow up by visiting Mediterranea at the business she inherited from her mother, a cheese shop.

She is surprised but happy to see him again, and she enjoys his candour when he admits since meeting her in his son’s office he has walked past her shop several times already, trying to screw his courage to the sticking place before finally coming in. From this small beginning something rather wonderful begins to blossom, at a time of life when neither really expected any such thing.

There are a myriad of very fine touches throughout Blossoms in Autumn, not least the superb translation work by Matt Madden. Translation, like editing, is often an almost invisible job – handled very well it is all to easy for the reader to forget that someone other than the writer and artist had a hand in the work they are reading.

Good translation requires far more than a literal swapping of words from one language to another, it also requires the delicate interpretation by the translator of not just the words, but the meaning and style the original language writer is trying to convey, then writing something in English which will carry that meaning in as similar a fashion as possible. Madden’s translation work is quite excellent, carrying the deep emotional undertow of the book into English in an elegant and deeply satisfying manner.

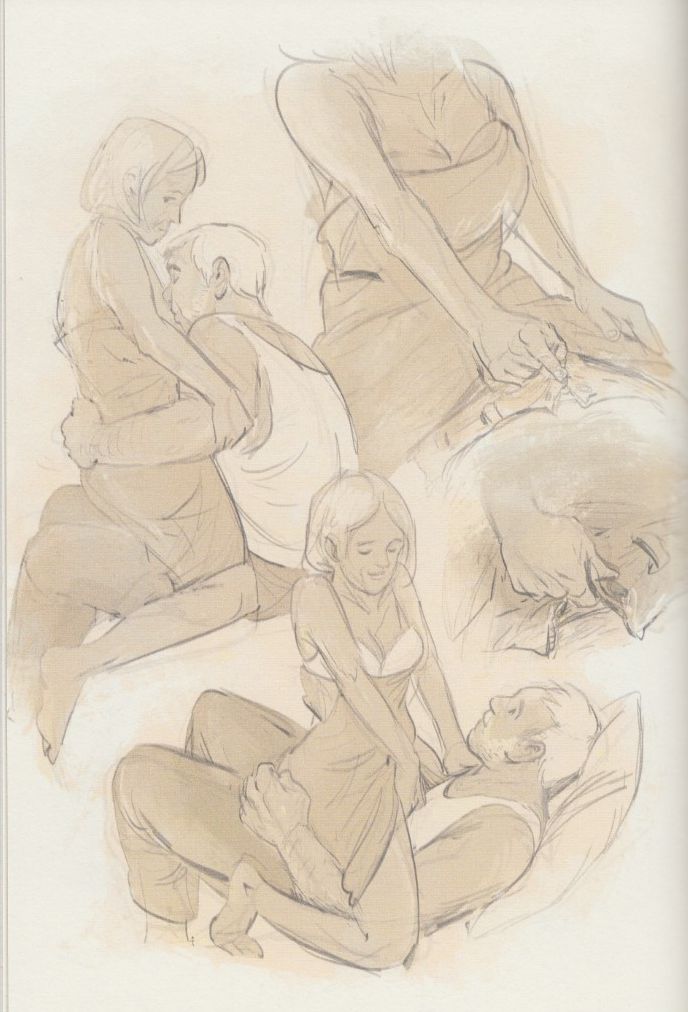

Other lovely touches abound, such as Zidrou and de Jongh arranging crossover cuts from Mediterranea to Ulysses, like the opening scenes I described previously, slowly intertwining their lives, or later, once they are just starting to see each other he finds out that in her youth she was a model and even appeared in a famous magazine, naked. Ulysses finds a vintage copy of the magazine in an old shop, but when he gets home he finds himself troubled, his desire to see what Mediterranea looked like déshabillé in her youth fighting with a sense of unease, that it is unfair, perhaps almost cheating on the older Mediterranea to do so. This cross-cuts with Mediterranea herself, viewing her naked body in the mirror, musing on age, on how that pretty young model could now be in this older woman’s body.

It’s a lovely bit of cross-cutting, and again it reinforces the intertwining of both of their stories into one, or the way another, happier change in their life is viewed through a change to a much softer pencil work, almost sepia toned artwork.

There’s a lot more in this rich, deeply emotional and satisfying story, that handles romance but without ever being sugary or saccharine, instead remaining believable, and laced with some of that humour that just comes out of everyday life and situations in places. A beautiful, warm, joyful story, deftly handled by a writer, an artist and a translator at the top of their game.

Joe Gordon

[amazon_link asins=’B07NPSBNCH,1772620394,1910593168,2818932165,B07CQ1KJ5J’ template=’ProductCarousel’ store=’downthetubes’ marketplace=’UK’ link_id=’5f46b754-d2c6-4993-a504-09e767b4dad3′]

Joe has been a bookseller since the early 1990s, with a special love for comics, graphic novels and science fiction. He has written for The Alien Online, created & edited the Forbidden Planet Blog and chaired numerous events for the Edinburgh International Book Festival. He’s more or less house-trained.

Categories: British Comics - Graphic Novels, downthetubes Comics News, downthetubes News, Reviews

In Review: The Legend of Luther Arkwright by Bryan Talbot

In Review: The Legend of Luther Arkwright by Bryan Talbot  In Review: Billionaires by Darryl Cunningham

In Review: Billionaires by Darryl Cunningham  In Review: “It’s only a movie…” – Reel Love

In Review: “It’s only a movie…” – Reel Love