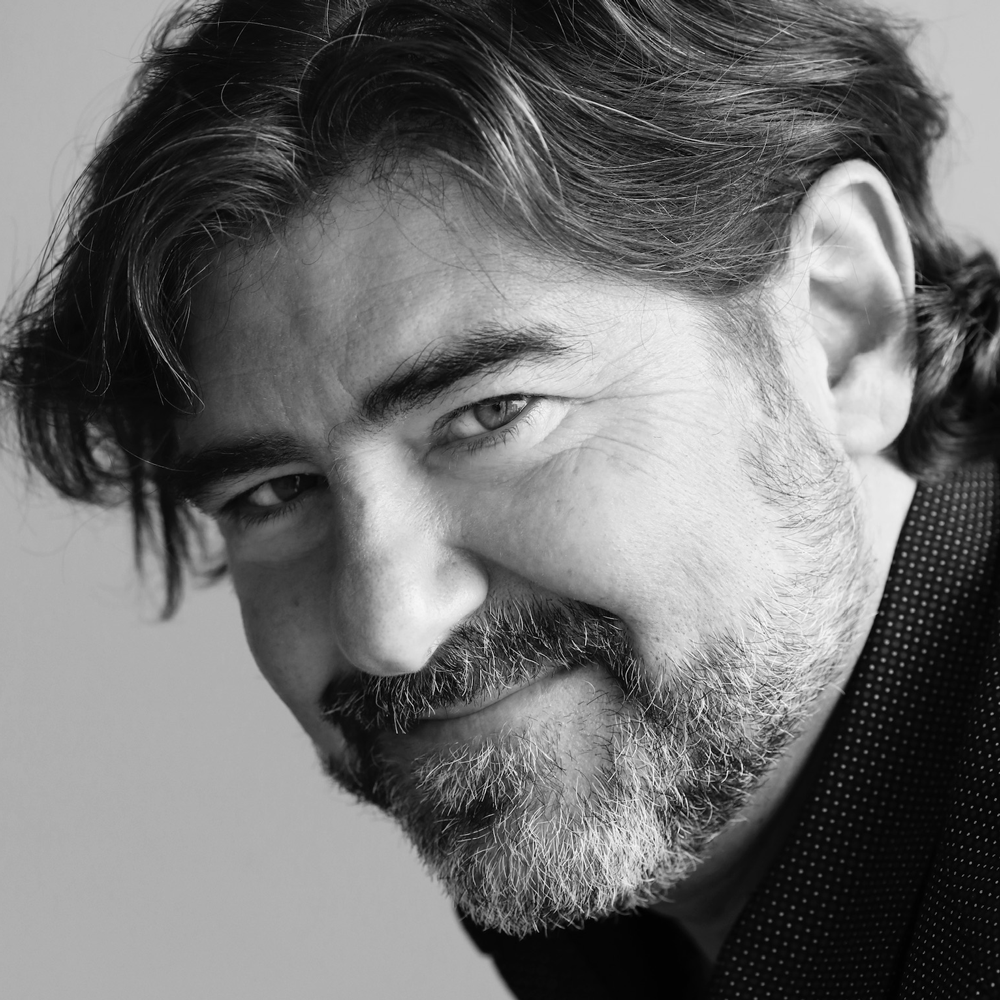

Juanjo Guarnido, the co-creator of the award-winning graphic novel series Blacksad, shares his passion for New York, appreciation of film and art with a love of comics. James Bacon caught up with the artist at last year’s Lakes International Comic Art Festival, but for a variety of reasons, his interview is only being published now… enjoy!

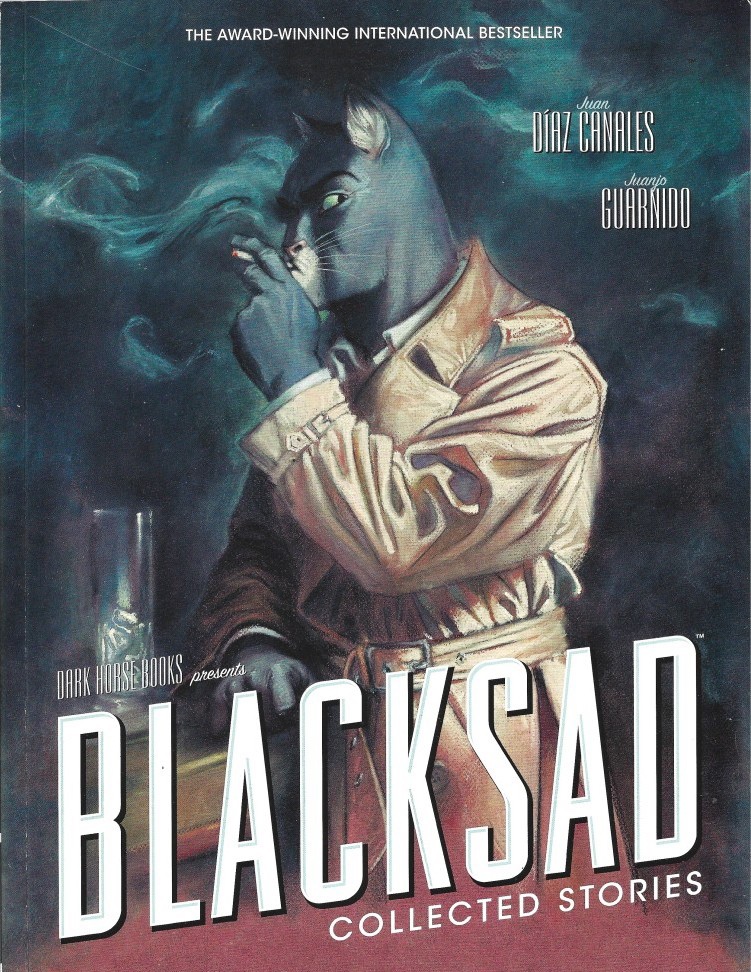

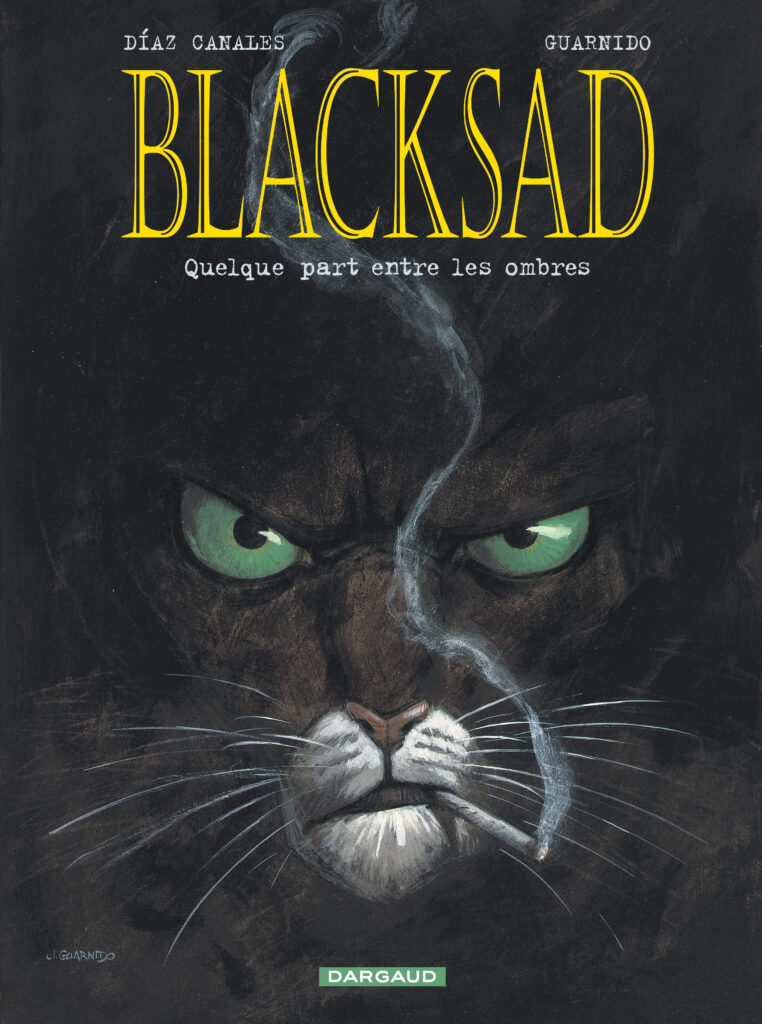

The Lakes international Comic Festival in Bowness-on-Windermere is taking place, and there are a host of wonderful comics creators in attendance. One of the guests is Juanjo Guarnido, artist and co-creator of Blacksad, originally published in French by Dargaud, and published in English by Dark Horse Comics.

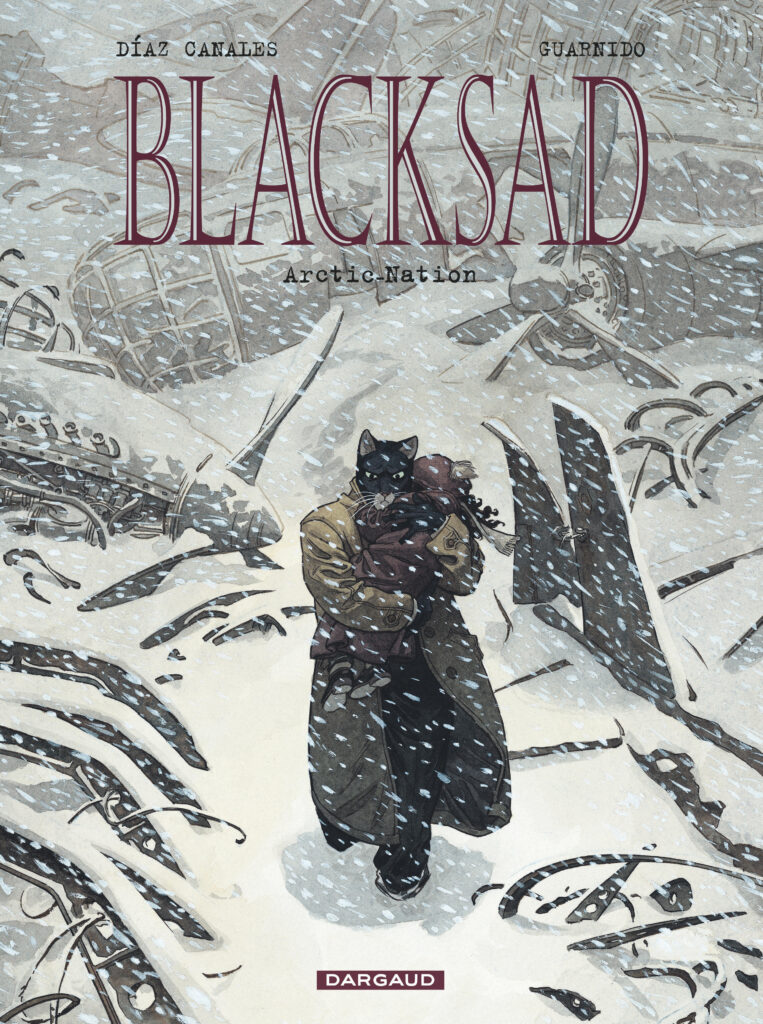

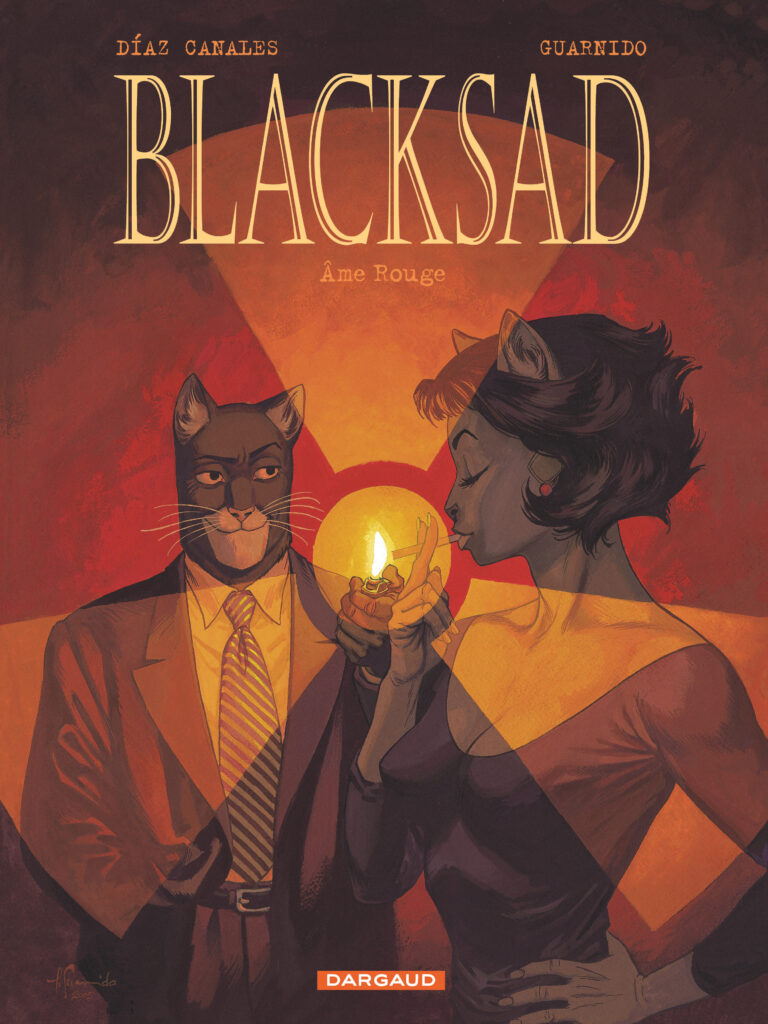

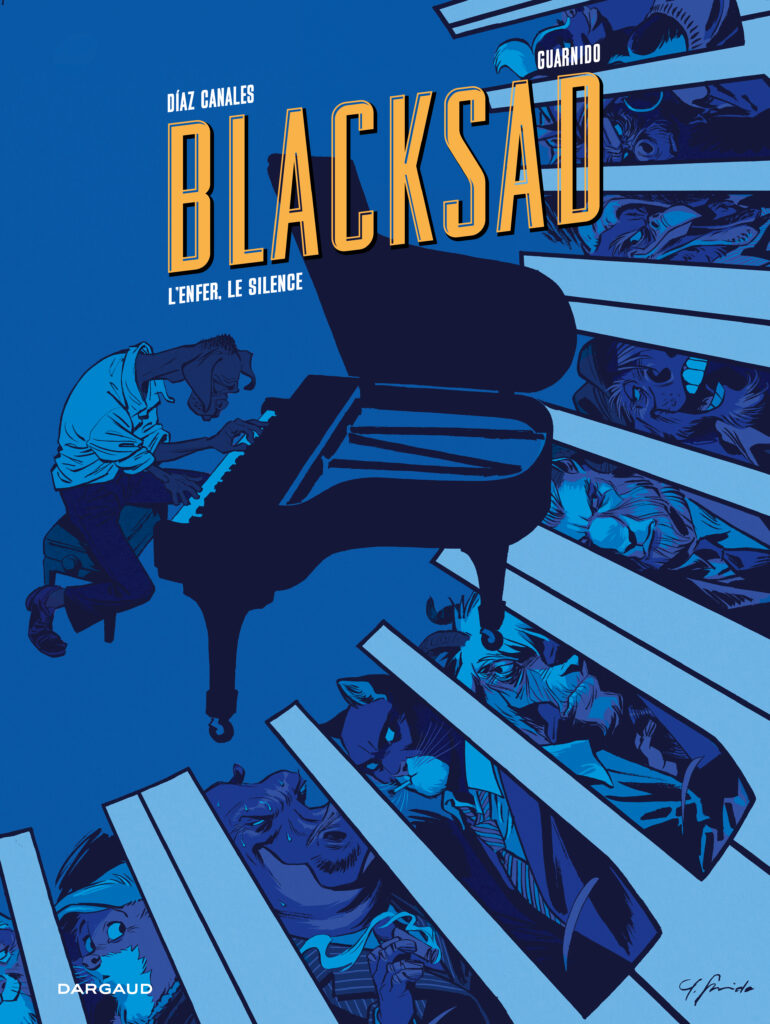

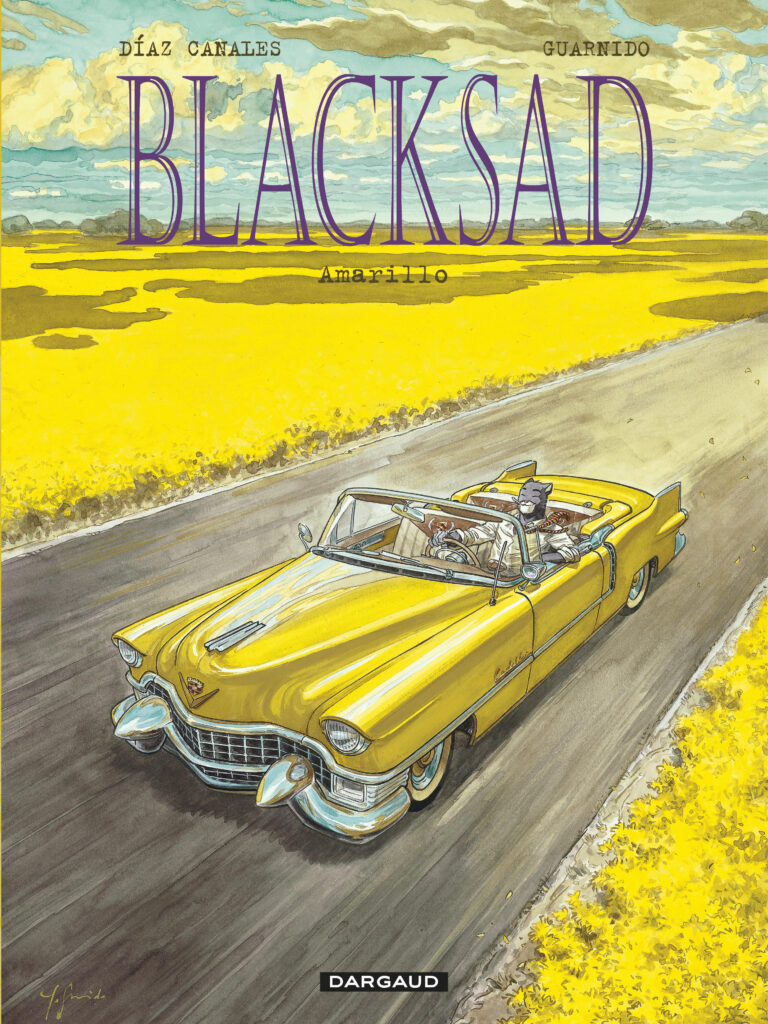

Blacksad is a pretty unique set of tales. Over 25 years, we have had a sequence of stories, initially published in French by Dargaud, with Blacksad, and continuing through Arctic Nation, Red Soul, Silent Hell, Amarillo and They All Fall Down Part 1 & 2.

The first three volumes were translated into English and released by American publisher Dark Horse Comics as a single graphic novel, entitled Blacksad. The series, which has won numerous awards, has also been translated into other languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Croatian, Czech, German, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Norwegian, Russian, Swedish, Turkish and Ukrainian. A video game adaptation, Blacksad: Under the Skin, developed by Pendulo Studios, was released in 2019.

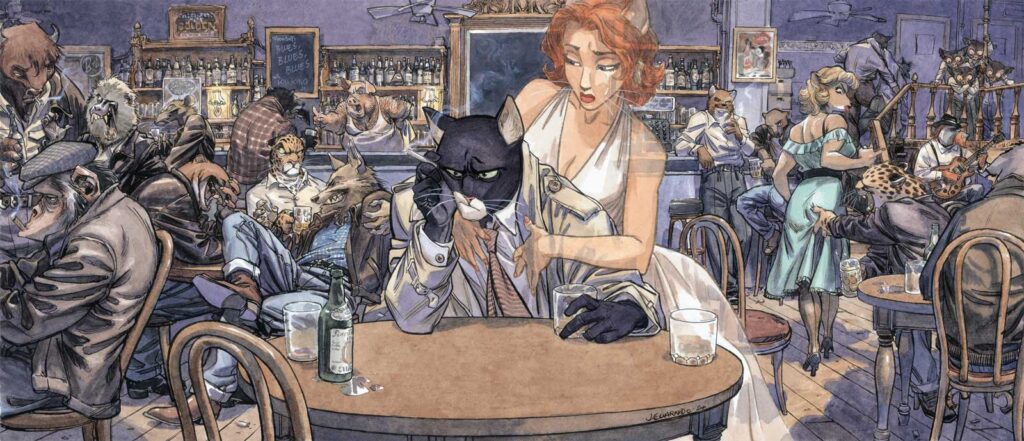

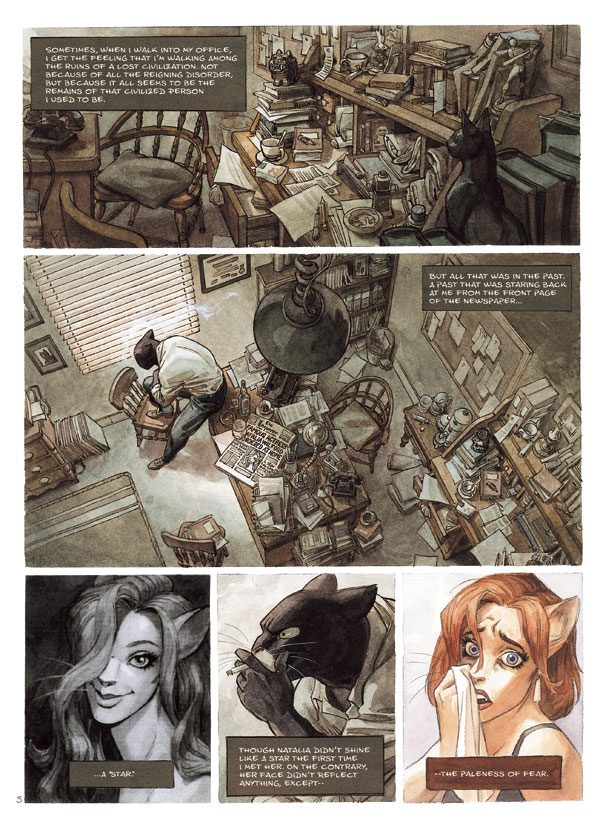

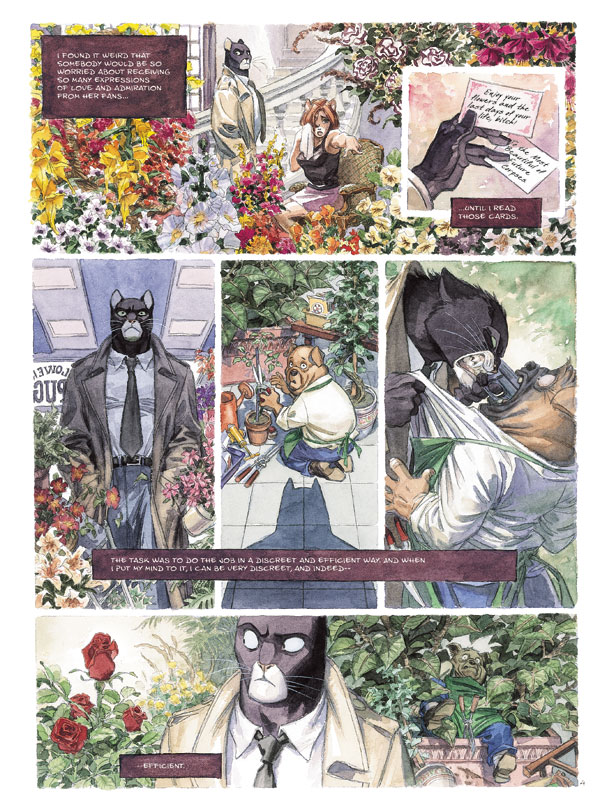

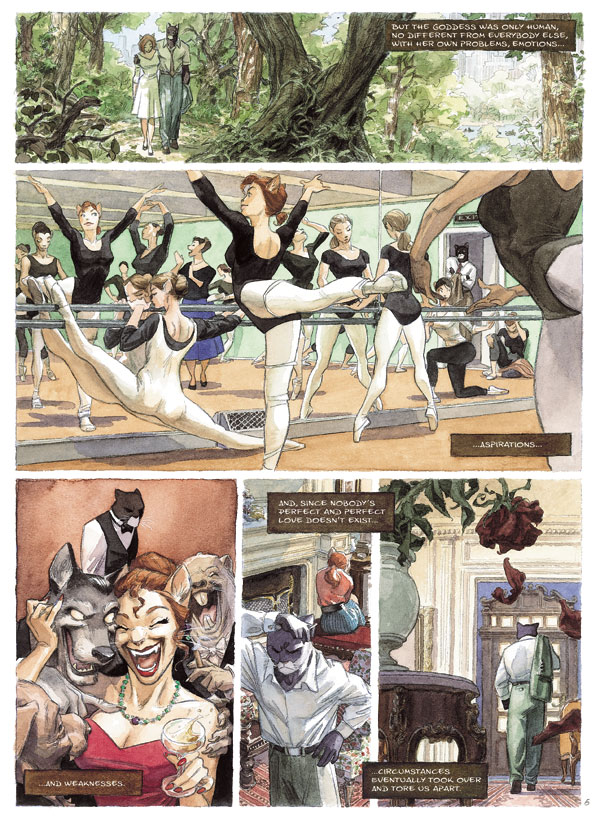

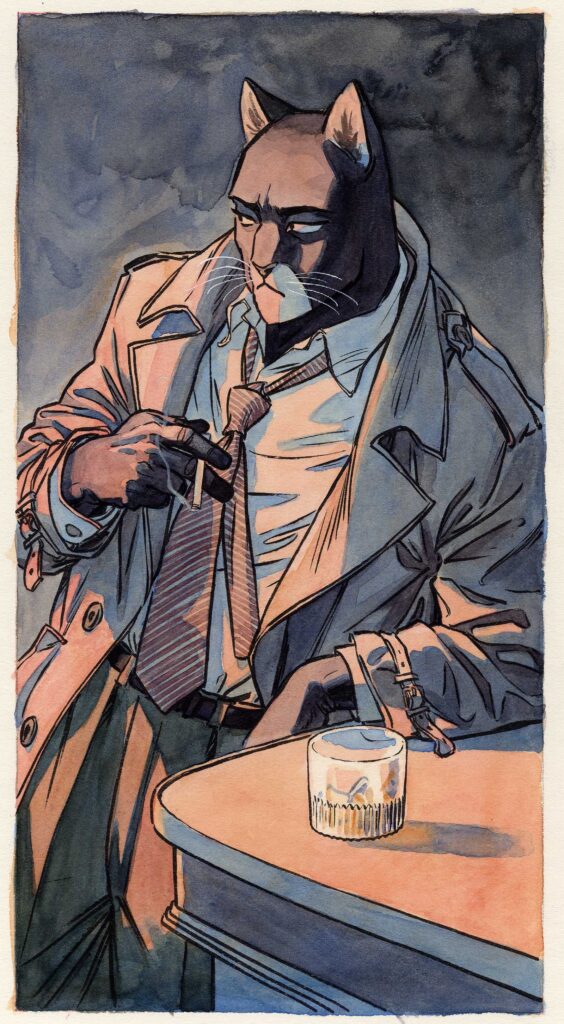

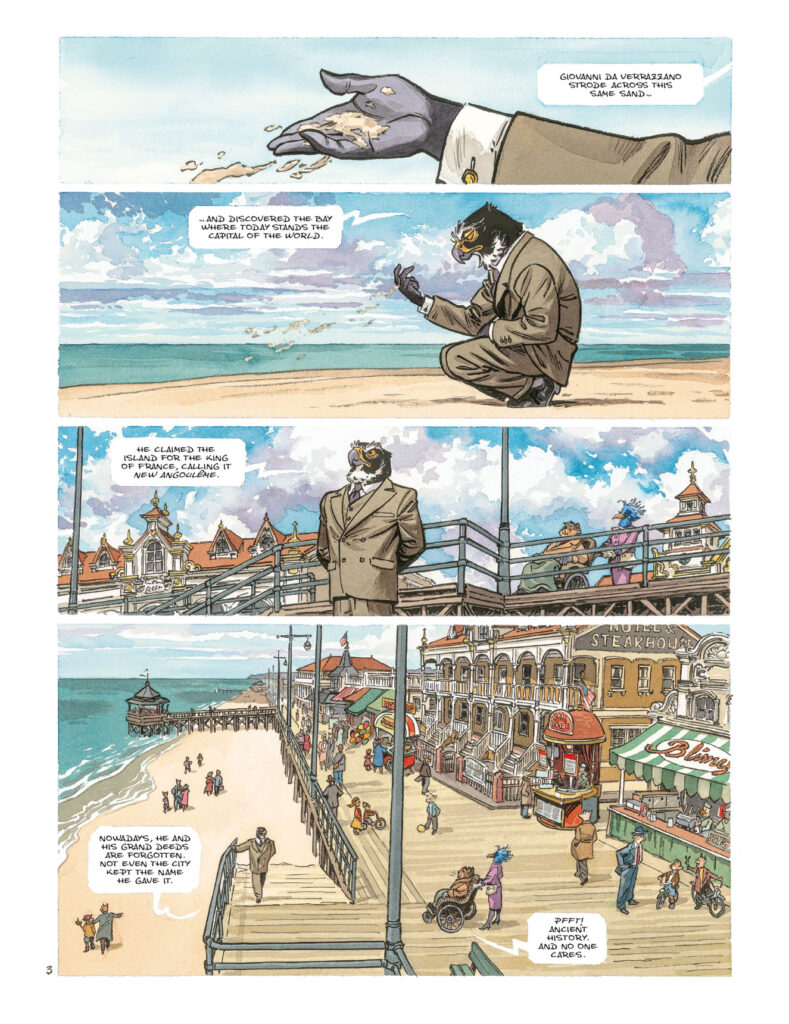

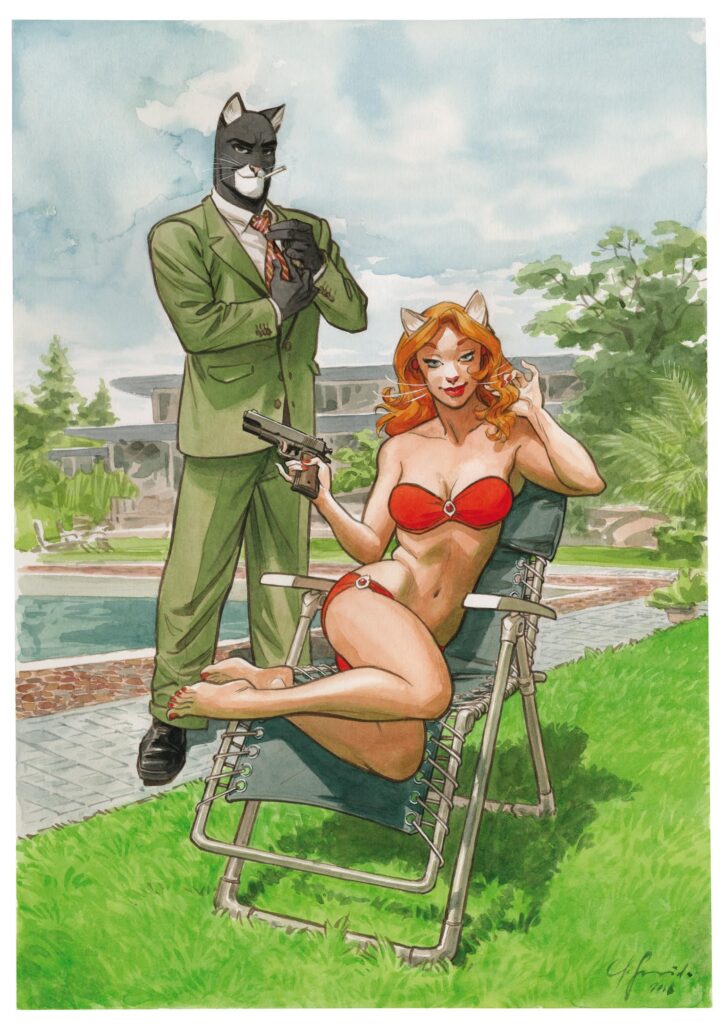

The first story introduces John Blacksad with an aspect that is utterly distinct. The anthropomorphic tradition is brilliantly utilised, with Blacksad portrayed as a cat, bruisers as a rhino and a bear, villains as reptiles and amphibians and animals such as rats. Women are not quite as strongly animalistic looking, and possess an exquisite beauty capturing their femininity very strongly. It is clever in its depiction, animal types fitting into tropes: police officers are often canine, so, dogs and foxes, and a boxer is a gorilla. The choices here are not arbitrary; there is thought to all aspects of the comic. There’s the moment in the iguana pub, for instance, where a mongoose walks into a bar of lizards and crocodiles, and one grabs him and yanks out a bit of fur… “You’re in the wrong hole, pal”.

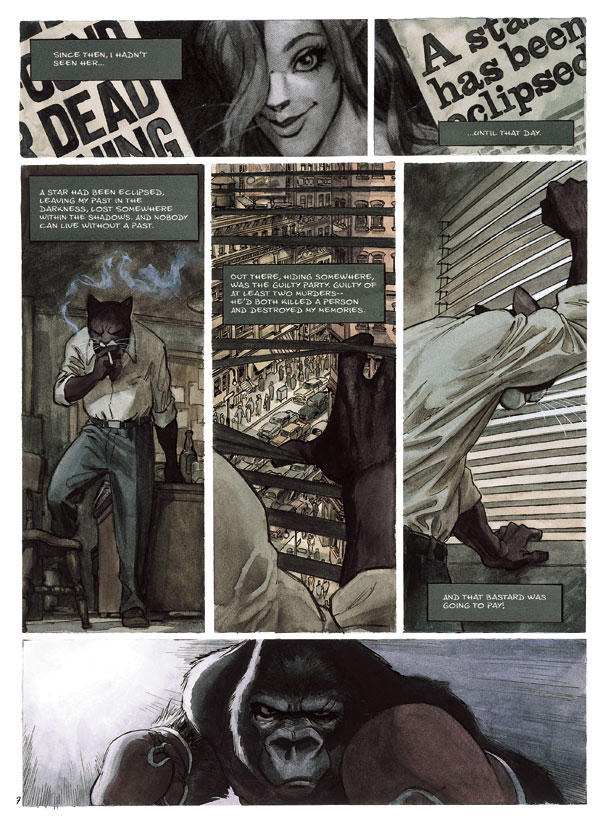

The setting is 1950s New York, and the architecture, vehicles, fashion and feel are impeccable. The story is a fine example of comic art influenced by film noir, exquisitely painted in a crisp fine line with water colours deployed to match the situation—shadow, muted, deep or beautifully bright complementing the story.

Then there is the criminal element, the crime story, that has some in shadow and others in light. The portrayal of the main villain in the first story of Blacksad is brilliantly done, playing on that theme, and we’re in a city where immediately we find that corruption, a cynical system, and a helpful and unhelpful moral flexibility and ambiguity exists.

Into this canvas we have comics’ finest hardboiled detectives, encompassing the elements that make great hardboiled fiction compelling, battling the violence of criminality while concurrently fighting their own inner thoughts, darkness, doubts, or self-pity. The focus is our detective, and there are often chinks of light in the darkness. While tragedy occurs, the stories are not noir fiction in the sense that our protagonists fall and suffer, where their sense of right and wrong becomes so entangled in their situation that a pessimistic and brutal end is inevitable. With Blacksad, thankfully, there is often hope coming through the sadness, bittersweet perhaps but triumphant even after the saddest moments of reflection.

Blacksad takes some of the finest elements of noir fiction, hardboiled stories and film noir and uses the artistic possibilities of comics to their fullest. Those possibilities, realised, are so beautifully portrayed by the artist, reflecting on such human themes as interactions, love, loss, jealousy, relationships, morals, right and wrong, and adding in the chase of the the procedural, the hunt, the detective, creating a space and dynamic with the animal species that allows for broader consideration of human issues and the political, corruption, race and racism, class and systematic issues, within societal structures.

It really is quite brilliant.

From the first story released in 2000, we feel empathy for John Blacksad as he is challenged by quite a traumatic situation. Blacksad has inner horrors and doubts, and he suffers trauma, both physical and mental. He can be brutal in his actions, often in self defence. There is not the outward unacceptable aggression, no deep personal self-hatred, that bends the mental understanding of what should be right and wrong. There is no descent into a controlling sociopathy, or psychotic behavior; if anything, this is what Blacksad has to fight against.

The comic has become huge internationally, translated now into dozens of languages. The stories are well read and loved.

Juanjo was happy to be interviewed for downthetubes. Our sincerest thanks to the LICAF team for facilitating this, and especially to Juanjo, who was happy to give so much time and energy to us, for our readers.

James Bacon (JB): Thank you Juanjo for speaking with us. To start at the beginning, were you friends with Juan Díaz Canales? Did he have the idea of Blacksad? Can you tell me about how the comic came about?

Juanjo Gaurnido (JG): Yes, we were friends. We started working together on an animation in this Madrid studio in 1990, and when we met, we got along instantly. We were a small group of youngsters. We followed the training, and it was a great experience for all of us. Most of us are still friends today and we were both very fond of comics, which we shared immediately.

I saw him as an artist because he is an artist – he draws very well, but he has potential for writing and we showed each other comics, the short stories we had drawn for ourselves and because we were trying to show them to the publishers in Spain at that time. I saw his scripts, which were great.

A couple of years later, when I was about to move to France to work for Disney, he first showed me and talked to me about the stories about this character.

He had invented a cat detective in a fable-like world, where the characters are animals.

And I said “oh, that sounds good” and I saw the stories and immediately, I was, ahhhhh, why didn’t I have this idea? This is fantastic, that’s a perfect comic for me. At the time,

I kept that to myself and sometime later, he told me we should do a comic.

Well, we always wanted to do something together, but maybe a short story. We had a projected seven-page story that was very interesting, but not very ambitious. It was just for the heck of it, for the pleasure of doing something together.

Then he told me out of the blue that we should do a real project. We should do a book, a whole book and I said “No, no you’re crazy, we are both working”. I was in France and he was in Spain, he was trying to build a whole studio, and I was working full time with Disney. I thought that it would be impossible, but he convinced me. He knows how to work his way with me, clearly!

But at the time, I thought it sounded crazy for me to take on such an enterprise. I thought that to do a book at this time would be crazy. Like very, very crazy, time consuming and energy consuming.

And I thought and said “Okay, but it has to be Blacksad” and he said “What? Are you sure?” and I was as sure as I lived and he said, “Well, let me think about it”. He thought about it like two hours and he said, “Listen, I think this is a great idea. Let’s go”. And here we are.

JB: The anthropomorphic idea was brilliant. Did you like drawing animals?

JG: Always. I grew up reading Disney, watching Disney cartoons, all the Carl Barks stories, Donald and Uncle Scrooge, the nephews and Mickey, Goofy and other animal characters, that were anthropomorphic, and also the European comic books. Anything with animal characters really caught my interest.

I loved Richard Scarry, and there was this great Illustrator in Spain who did things in a similar way, but Spanish and different, and I loved that. So, so, so, so beautiful. I love all that.

I love throwing animals in complicated situations with a lot of characters, telling the stories with the details. I loved all the all this stuff, and my own comics that I drew as a child, I invented stories, and I would lay them down like comics and sometimes I would even staple them to have a whole magazine.

JB: Your animals are very realistic…

JG: At that time, it was only cartoony drawing and very clumsy, because I was a child. I was six seven, eight, but I was already doing all this and my drawing evolved, and I grew up and I was more in search of an accurateness and volume, a realistic effect, lighting, not so much colour. The colour came after I went to Fine Arts school, when I started to understand its importance. Then my experience at Disney was of course crucial.

JB: That’s really helpful. It helps to understand because there’s such a strong level of detail to your animals. The faces seem very important to you, the emotion, the reaction – do you spend a lot of time thinking about how the faces will look?

JG: I don’t think about it. It’s just self-evident. In my youth, the comics I preferred were the ones in which the facial expressions were strong. We have this artist in Spain, Alfonso Font, and the facial expressions of his characters are unbelievable. So expressive.

Then I discovered European cartoon characters. I always loved the ones with the most funny expressions. When I discovered Asterix, I was like, “Oh my God!” That was like a a slap in the face – a face-turning slap!

It was not only the facial expressions. The body language and all that is so important to the story. Those are storytelling elements.

JB: Blacksad is influenced by film noir. It’s a very cinematic feel. Were there actual films or a particular aspect that you were influenced by?

JG: Yes, totally, the film noir of the thirties and forties. There’s a span between The Public Enemy with James Cagney and Jean Harlow in 1931, through to Anatomy of a Murder in 1959, American-produced and directed by Otto Preminger. Anatomy of a Murder and all that black and white – a beautiful, amazing collection of movies that is my main inspiration. Then there are some colour films near the end – you can’t ignore North by Northwest, set in Indiana and South Dakota and so many amazing scenes. I’ve copied from settings and camera angles.

JB: Fans recognise that, do you spend a little bit of time having fun with that?

JG: Fans get those references, which makes me very happy, and of course, it’s always,

effective. When that the readers come to you and tells you this is from this movie, it’s a huge satisfaction to see that that you send this message in a bottle into the sea and it arrives into to the hands of readers, to the destination, and they catch all the small messages, all the references. That’s great.

JB: And this it’s not just films. There’s often fictional crime references as well, and references to art. Do you enjoy that?

JG: I do. When we have four musicians, in New Orleans and there is a donkey, a cat, a dog, a rooster, and the turtle in a Norman Rockwell style, it’s a reference to the Norman Rockwell painting.

We have so many references here and there. Anytime you put your work out there, you put your heart into it, and the work goes out there and reaches people and you are getting in touch with them, and with small details it goes a little further, it goes a little deeper. That’s fantastic, it’s like shaking hands, like saying I got you with those details.

JB: The architecture, the vehicles, the clothing, the fashion of 1950’s New York, these are obviously very important to you to get right. Do you spend a lot of time researching?

JG: That’s a lot of work. Yeah, that’s a lot of research, of course. In fact, in the beginning, it was hellish to do that. It was very, very difficult to find all the references, because it’s not like how it is now with the internet. You find anything you want now, anything that’s being photographed, but I’m very careful to not use anybody’s work without permission. But you have all the reference you need and the pictures of the places on Google Earth. You can go even into one precise street in New York and see what exactly is the angle, and how other building appears.

I like that. I like this research work very much, but when I first started, you had to actually buy books, buy picture books, photograph books from the early decades of the twentieth century.

Today, I use a lot of my own of my own research and my own photographic research and my own photographs, because I went for the first time to New York when I was 22, right, in 1992, and I took some pictures – but not many, because I wasn’t working on Blacksad then.

I would some years later – I have taken hundreds, thousands of pictures even, but at the time, when it wasn’t digital photographs, it was very expensive to develop photos.

I found when I was working on the first Blacksad that there was an important moment. It was amazing. I was going through a Bernice Abbot book of New York photos in the 1930s and there, near Macy’s, there is a photograph and in the background is the Empire State Building. It’s in the background, and I say to myself, “Wait a second,” and I go to my own pictures from 1997, from my second trip, and I got many picture from that second trip. And I think “Wait a minute, I’ve seen this place” – and I had the same picture, with the same angle. I was standing at maybe a one-yard radius of where the photographer was standing. Exactly the same place, and it hadn’t changed at all, the buildings were exactly the same.

From then on I developed this thing where I walk through New York. I love walking in New York. I’m going to spend a month there from next week. I go every year if I can spend three, four, or six weeks there.

I can walk through New York and forget all the modern buildings. I like them too, but I can see it as if it was in 1940s and in the 50s.

As we talk, Juanjo’s passion comes through here during the interview – his enthusiasm, passion and energy is incredible and infectious. Here is someone who is smiling, yet thoughtfully intense about what they do. His wonderful positivity may not come through in words alone!

JB: Thank you. What you share that with us becomes infectious. Is there a particular year that you have chosen?

JG: It’s in the 1950s and we even take some elements from the from the 60s at some points. We placed the story somewhere in the first half of the,of the 50s, but it’s all it’s a bit tricky, and we take a lot of liberties creatively and artistic license in covering the whole decade. We are in the 1950s, the cars are the cars from the 1950s. The people, the fashion, is the fashion of the 50s and so on. I think it works like that, and people accept the small liberties that we take once in a while.

JB: Did you read American comics as well? Your layouts are traditional. Like, were there any American comics that influenced you?

JG: Yes, many influences. But for that particular field, actually, my main influence is the years of doing layouts in animation. When I was hired as a layout artist, I was laying out The Hunchback of Notre Dame, the Goofy movie and the Mickey Mouse film, Runaway Brain. Then I asked for training on character animation, because that was the thing that was dear to my heart. I always wanted to do the animation thing, it was just magic for me when I was a child – all the Disney animation shorts and feature movies – so yes, a magical aspect.

I’ve always been attracted to or interested in drawing. It’s not even an understatement to say it’s part my life. It’s part of me, in the DNA probably, totally, part of my of my soul, and who I am. I know today that once I won’t be able to to draw, I will die, I will die of self-combustion or something. I would just drop right there because it’s who I am and who I have always been.

My first contact with American comics was Spider-man. This guy from my school had a Spanish edition, and I was told that it was about “a sorcerer who pulls spiders from his veins.” Oh, that’s scary, I thought. I want to see it, where is it?

It had nothing to do with what he told me, what is this? This is just a young guy, he gets bitten by a spider and then, oh my God, he has powers. This is amazing! This is fantastic!

I felt completely in love with Peter Parker and ever since he’s always been my favourite character in in American comics – and then I discovered more, of course, all the other superheroes and then later the classics. I have some comic art but I’m mostly a collector of American classic illustration.

JB: Do you have a particular illustrator you really enjoy?

JG: Yes. Well, many. Coby Whitmore, and I have several illustrations by Bernie Fuchs who did the portrait of Kennedy, and I have a several by Oliver Hurst, one of my favourites.

And Charles Dana Gibson, I have one. I have many beautiful pieces, but one was sold to me by Julie Major, as we have common acquaintances. I have one piece, one of the best of my collection, the last drawing on the Mr. Pipp series. It’s the one where he’s holding his grandson and granddaughter. It’s so beautiful.

JB: And Rockwell? Have you been to the Rockwell Museum?

JG: No, because I’ve never been to Stockbridge, but I have gone to several exhibitions, I have taken trains and I have travelled to see Rockwell’s exhibitions, and the last one was three or four years ago in France. It was in Caen, at the Debarkment Memorial and it was a huge, beautiful, amazing, Rockwell exhibition. The best I’ve seen so far.

JB: New York of course is a very Marvel setting. Your passion for the city comes across. Were there any other influences?

JG: I think probably New York is like a best friend. Actually, with Blacksad, the fact that I had to research so much, that I had to get into all of New York, into the mid-century New York, I became more fascinated, and this added to my passion. I love to take pictures, and some pictures virtually do not change and that is very nice, but I also have to update.

I’ve become more and more passionate, and something changes when I visit New York.

I love the city. My first time in 1992, I was totally fascinated, but I was young, and it was a bit scary. I was intimidated by the city and at the time it was a bit dangerous. It wasn’t like later, or now, and at some point, probably 2010, when I went to my first Comic-Con in New York, that I started really to be deeply deeply fond of the city, and started enjoying it. I started to love it more, feeling deeply about the city and fitting in and feeling that it is the place where I am at home.

No, it’s not. No, no, maybe I’m lying – it’s a place where I feel best, where I feel happier. I don’t feel home because I know I’m a stranger over there. It’s incredible. I feel so happy there and so excited by everything and so energized. I’ve had some energizing experiences in New York that are really something else, but I’ve been to other places. I’ve been to Los Angeles and San Francisco, I’m very fond of the Bay Area there. I went to the to the Big Wow Festival in San Jose with my friend Steve and it was great. I’ve travelled to the national parks in America. I’ve been to a Charlotte convention and to New Orleans. New Orleans is another beautiful experience.

JB: It’s clear you really like many places in the United States. New Orleans is another inspirational source for you that comes across in the comic, doesn’t it?

JG: New Orleans, yes. yes, that’s totally true. I went to New Orleans. and I wasn’t expecting what I found.

I had already started my work on the book and I started over, because I realised that I was drawing a city that wasn’t it at all, not by any chance similar to what it was. I was doing something totally different, invented, a city that had no soul, or or interest. I love the city so much that I spent the following year making a book for other people to know and love New Orleans.

JB: Blacksad has become hugely popular in English reading-places, it has travelled across from European comics, not unlike the success that Hugo Pratt had with Corto Maltese and Moebius had too, which is uncommon. How do you feel when your work on Blacksad is considered like this, and the popularity of the comic?

(To readers, I have obviously surprised Juanjo with this question, and comparison, and his humility here, one can see how honoured he is, so delighted in the success, but grateful)

JG: The success? I’m thrilled, right? I’m thrilled. But it’s hard to believe, because I don’t have an explanation. I just acknowledge it with thanks, that Blacksad is one of the European comics that has a huge success in the English-speaking market. Of course we had Persepolis. Blacksad has reached a large public, and I don’t know why, I don’t have an explanation, I just have to watch and acknowledge it and be utterly happy about it.

Blacksad is a charismatic character, but it’s on another level, surprising, but so, so pleasant,

JB: Politics comes through. While it’s a hard-boiled, detective story, with positivity and optimism there is also a harder politics too, racism, class. Do you like the hints, gently emphasising the reflection on of our own world?

Do you like it when readers are forced to think a little bit?

JG: Yes, I do. Juan is usually responsible, because he decides what appears in the stories and when I have an idea to put in the story, we get together and we discuss it. Of course, he has the last word on that, he has to validate and approve everything. There is no reason to not include interesting and important themes in a mainstream comic book. It’s there for the mainstream public, and it’s entertaining, and it has to be entertaining and good quality and accessible, The drawing style is big for me, for the public, but that doesn’t mean that we can’t talk about important matters.

A couple of times I have had to tell him maybe that there’s always a political stance, but let’s maybe do it a different way. I have been moderating voice sometimes.

JB: Subtlety and nuance works well though?

JG: Yes, yes, that’s what I think. I think it works always better.

JB: Finally, are we allowed to know what you’re working on at the moment? Are there any future plans for Blacksad ?

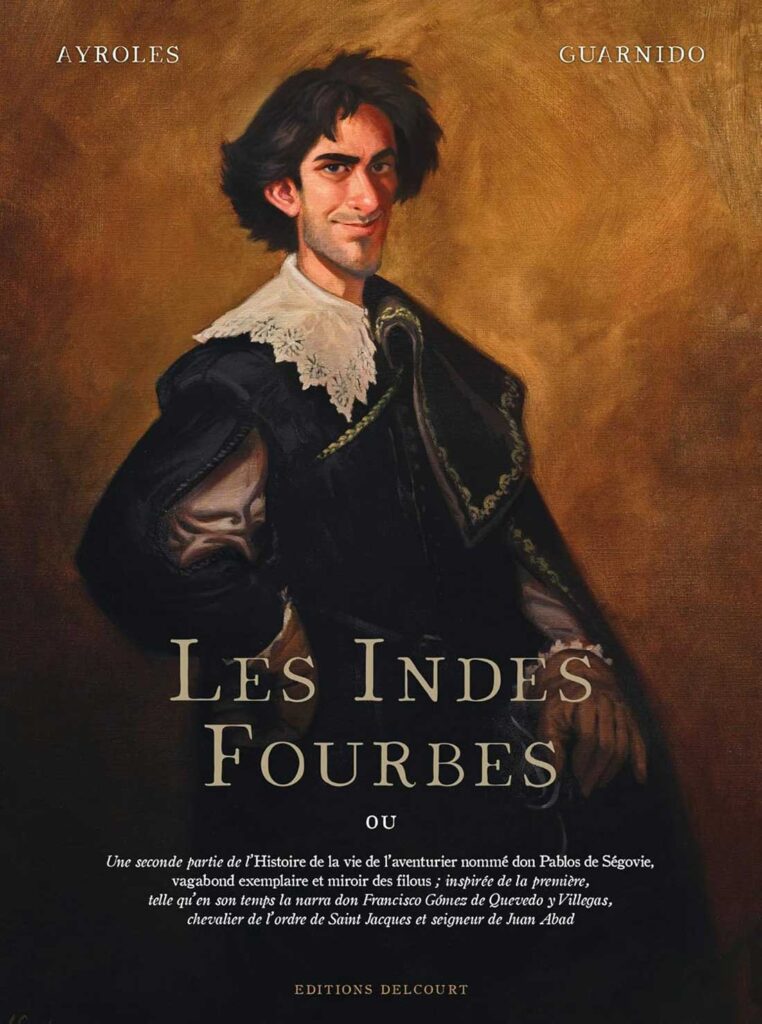

JG: Yes of course, we’re going to continue, and we have plans for the next couple of Blacksad books, but before that I am starting to work on a on another book with Alain Ayroles, who I did Les Indes Fourbes (“The Deceitful Indies”, 2019) with. It was a success and people asked us, “Are you gonna work together again?” And when we were signing and we would look at each other and said “Yeah. Oh, what do you think? Yeah. Why not. Why not?” It went well, so, why not do it again?

At some point, he told me about an idea that he had written a treatment for and he explained it, and he sent me the pitch for the project, and I was silent for less than half an hour. I was, “Okay let’s do it.” I mean, it was immediate, so we started on that a couple of years ago. We started the intro, the first act, which is huge and important, and it went wonderfully, but he has to write the rest of the book. So because of that, right now, we don’t know if it’s gonna be a one hundred or two hundred-page book. He knows the story, but we don’t know how the storyboard is gonna go and how many panels.

This will be another book like the Les Indes Fourbes, a big book, a one -shot book, which is great for the for the public, because they have a long reading experience and a very nice book with a lot of pictures and and a very interesting story. I hope people will like this story too because I think it’s fantastic,

Juan is working on Corte Maltese now, but he takes some time to write his ideas and he collects them and gets them together, ready for working, and I know it is not yet written, but we have many ideas in in the back of our minds.

The interview ended there, and I noted that like other readers, who savour the work that is Blacksad, I will have to be patient. But that patience is well rewarded, with such quality stories. I was grateful to Juanjo for sharing so much: he was open, effusive about comics and art, and a delight to engage and chat with, his enthusiasm and love was infectious, and he was so good humoured, which I hope comes across.

Our thanks to the Lakes International Comics Festival and John Freeman and Carole Tait for helping make this happen, and especially to Juanjo, for his courtesy and generosity of time.

Head downthetubes for…

• ComicWatch: Translating BLACKSAD: A Conversation with Editor and Translator Diana Schutz

• Blacksad – Dargaud (French Editions)

Blacksad: The Dark Horse Editions

• Check out the book on the Dark Horse site

Blacksad

By Juan Díaz Canales (Writer) & Juanjo Guarnido (Artist)

ISBN: 978-1595823939

• Buy it from AmazonUK (Affiliate Link) | uk.bookshop.org (Affiliate Link)

Private investigator John Blacksad is up to his feline ears in mystery, digging into the backstories behind murders, child abductions, and nuclear secrets. Guarnido’s sumptuously painted pages and rich cinematic style bring the world of 1950s America to vibrant life, with Canales weaving in fascinating tales of conspiracy, racial tension, and the “red scare” Communist witch hunts of the time.

Guarnido reinvents anthropomorphism in these pages. Whether John Blacksad is falling for dangerous women or getting beaten to within an inch of his life, his stories are, simply put, unforgettable.

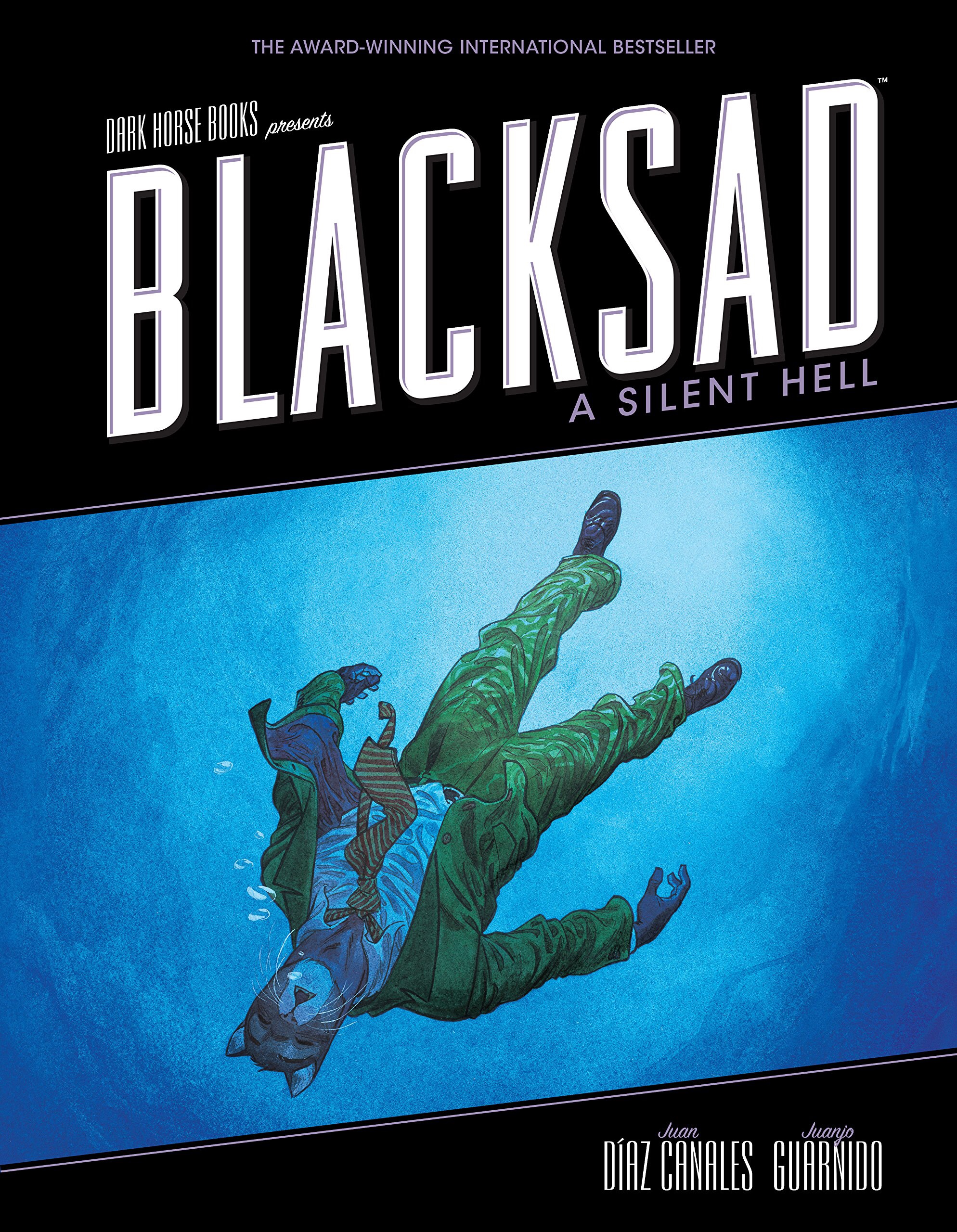

Blacksad: A Silent Hell

By Juan Díaz Canales (Writer) & Juanjo Guarnido (Artist) | Translated by Katie LaBarbera

ISBN: 978-1595829313

• Buy it from AmazonUK (Affiliate Link) | uk.bookshop.org (Affiliate Link)

Detective John Blacksad returns, with a new case that takes him to a 1950s New Orleans filled with hot jazz and cold-blooded murder! Hired to discover the fate of a celebrated pianist, Blacksad finds his most dangerous mystery yet in, the midst of drugs, voodoo, the rollicking atmosphere of Mardi Gras, and the dark underbelly that it hides!

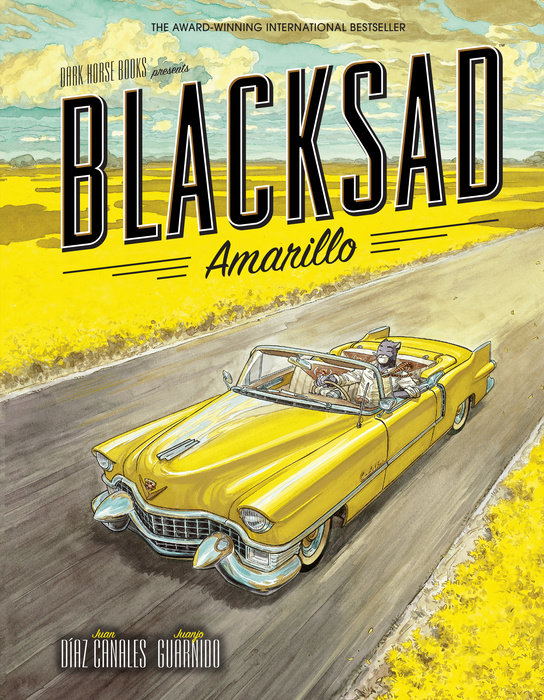

Blacksad: Amarillo

By Juan Díaz Canales (Writer) & Juanjo Guarnido (Artist) | Translated by Katie LaBarbera

ISBN: 978-1616555252

• Buy it from AmazonUK (Affiliate Link) | uk.bookshop.org (Affiliate Link)

Taking a much-needed break after the events of A Silent Hell, Blacksad lands a side job driving a rich Texans prized yellow Cadillac Eldorado across 1950s America, hitting the back roads from New Orleans to Tulsa. But before long, the car is stolen and Blacksad finds himself mixed up in another murder, with roughneck bikers, a shifty lawyer, one down-and-out Beat generation writer, and some sinister circus folk! When John Blacksad goes on the road, trouble is dead ahead!

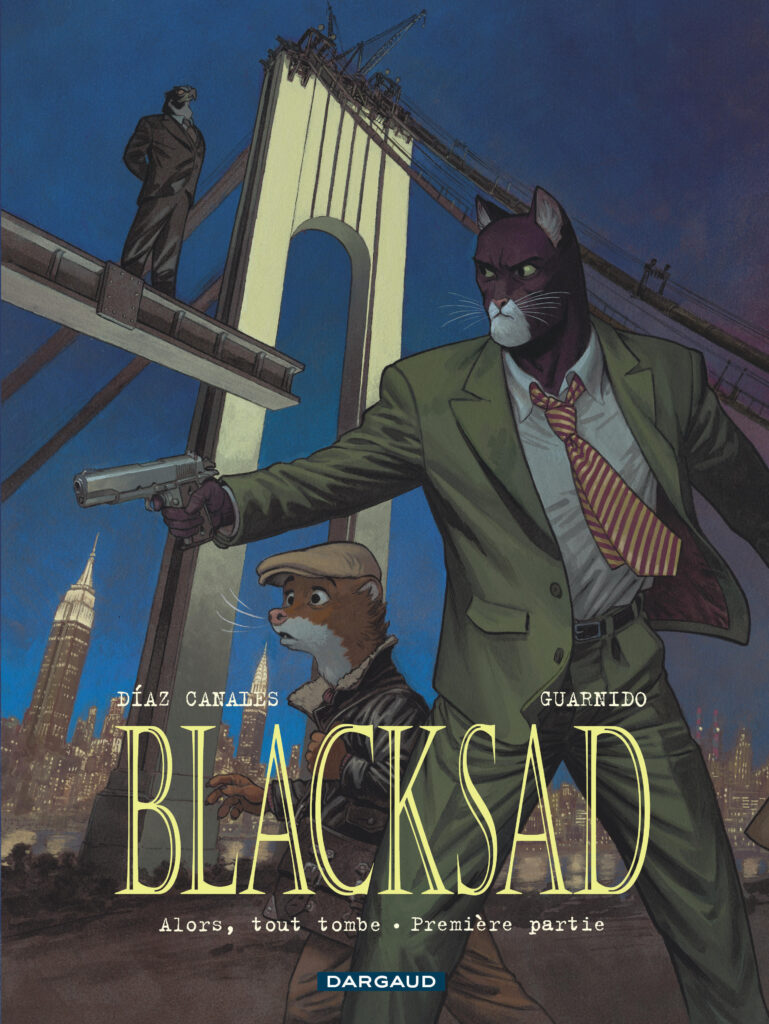

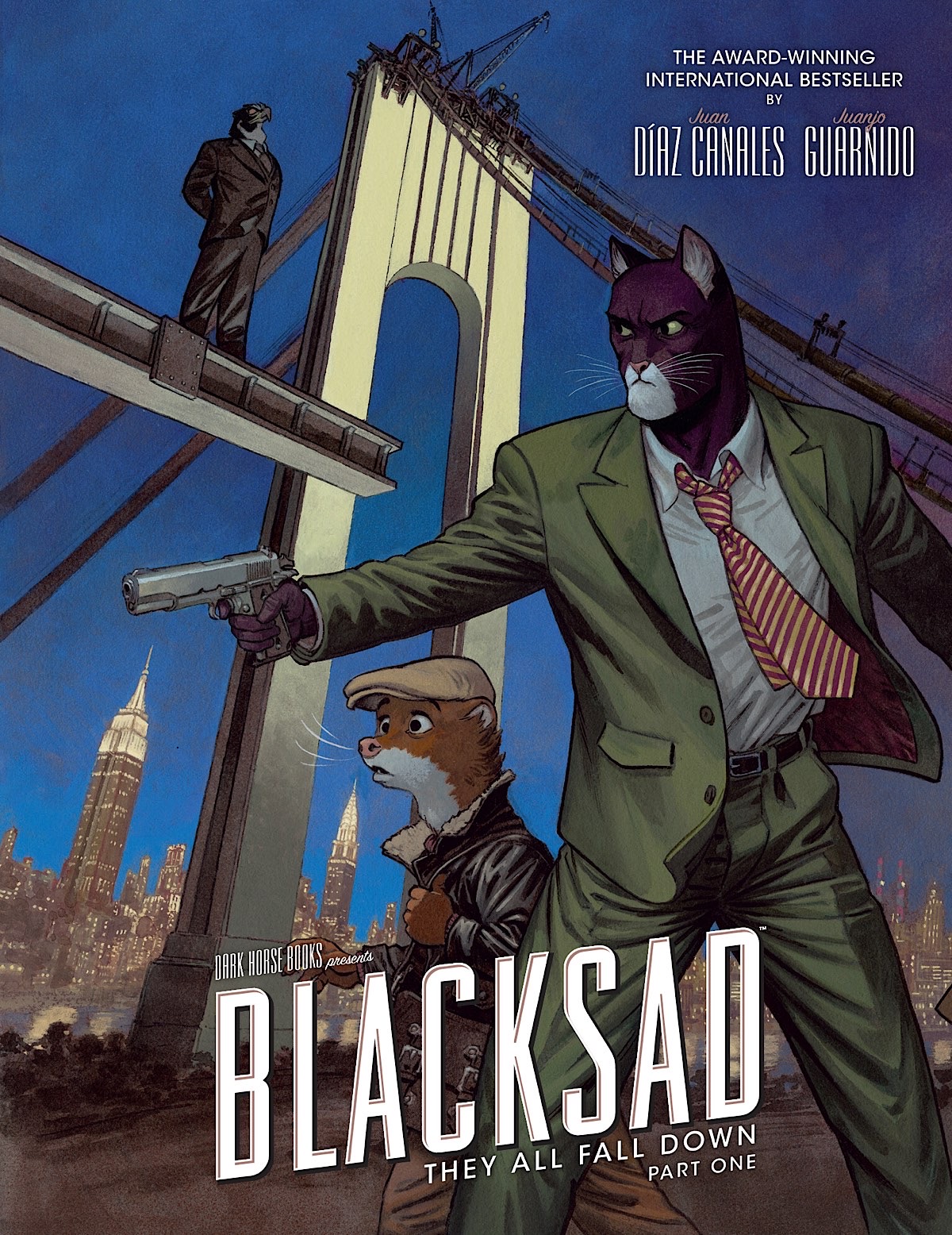

Blacksad: They All Fall Down Part One

By Juan Díaz Canales (Writer) & Juanjo Guarnido (Artist) | Translated by Diana Schutz, Brandon Kander

ISBN: 978-1506730578

• Buy it from AmazonUK (Affiliate Link) | uk.bookshop.org (Affiliate Link)

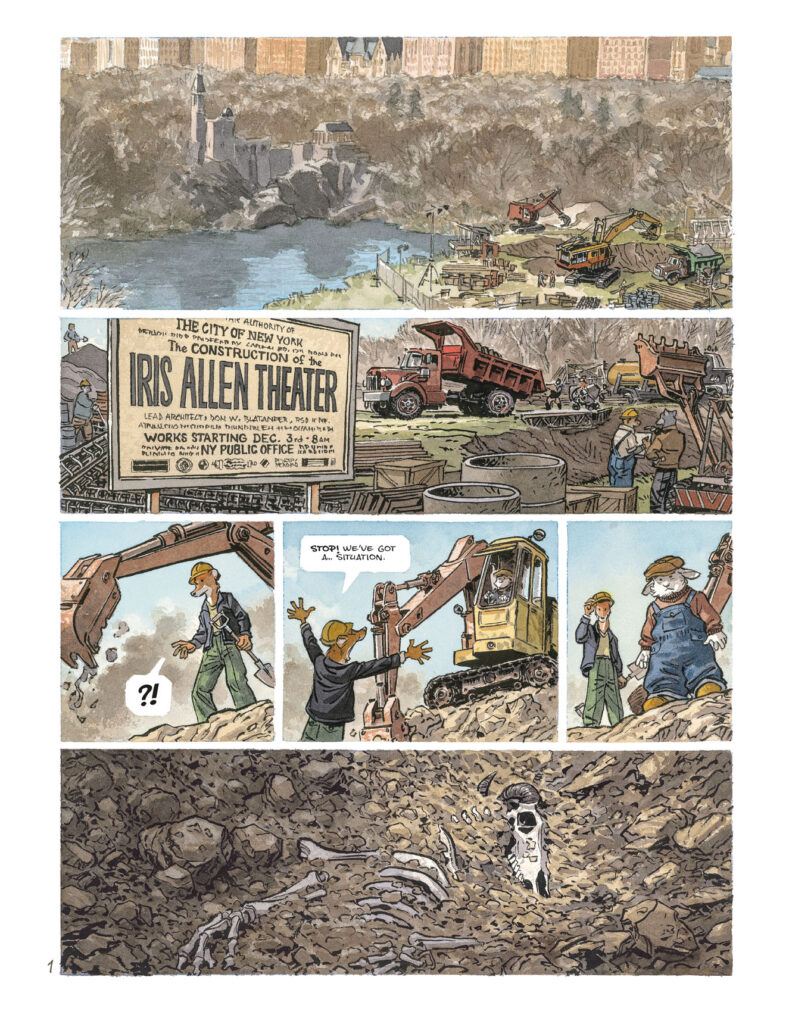

In this exceptional noir tour de force from writer Juan Díaz Canales and artist Juanjo Guarnido, the hotly anticipated worldwide bestseller returned to American shores after a seven-year hiatus, with a brand-new two-part storyline! Following its chart-topping 2021 release in Europe and now translated for English-language readers by the team of Brandon Kander and Diana Schutz, this volume features feline private eye John Blacksad as he tangles with the unions, the mob, and mid-century construction magnate Lewis Solomon, who plans to pave New York City’s green space, come hell or high water. From soaring heights to terrifying depths, Blacksad must steer the right course between the lofty world of Shakespearean theatre and the seedy nether regions of the city. Towering above it all is the foreboding figure of Solomon, who will let nothing thwart his dream of power.

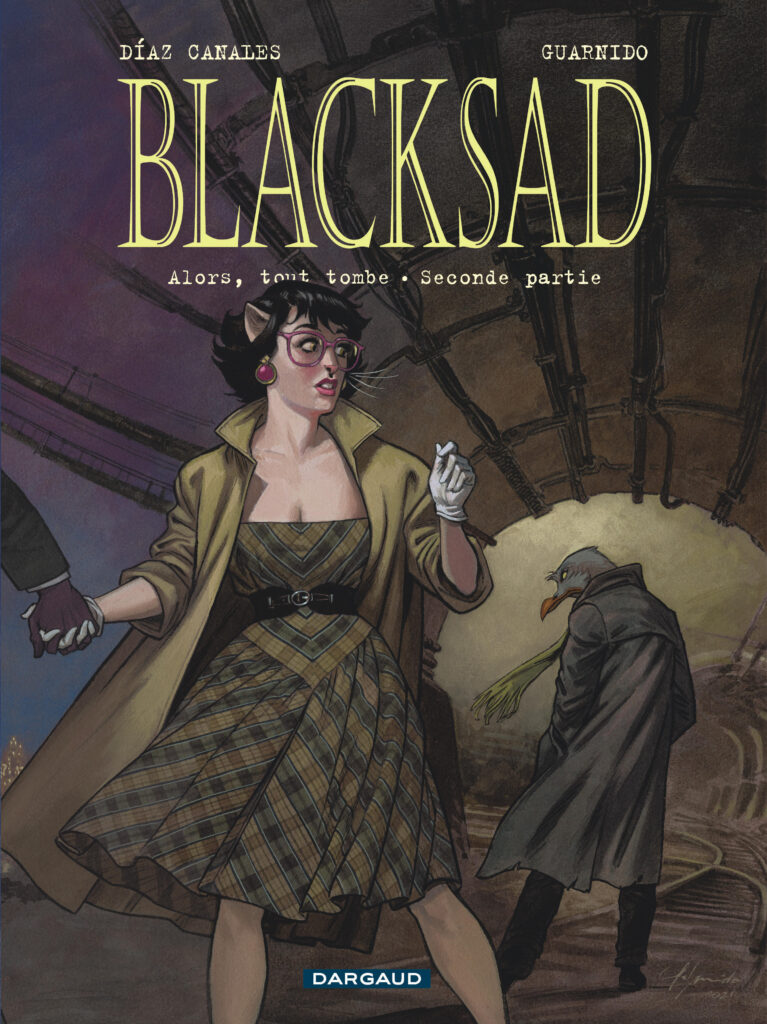

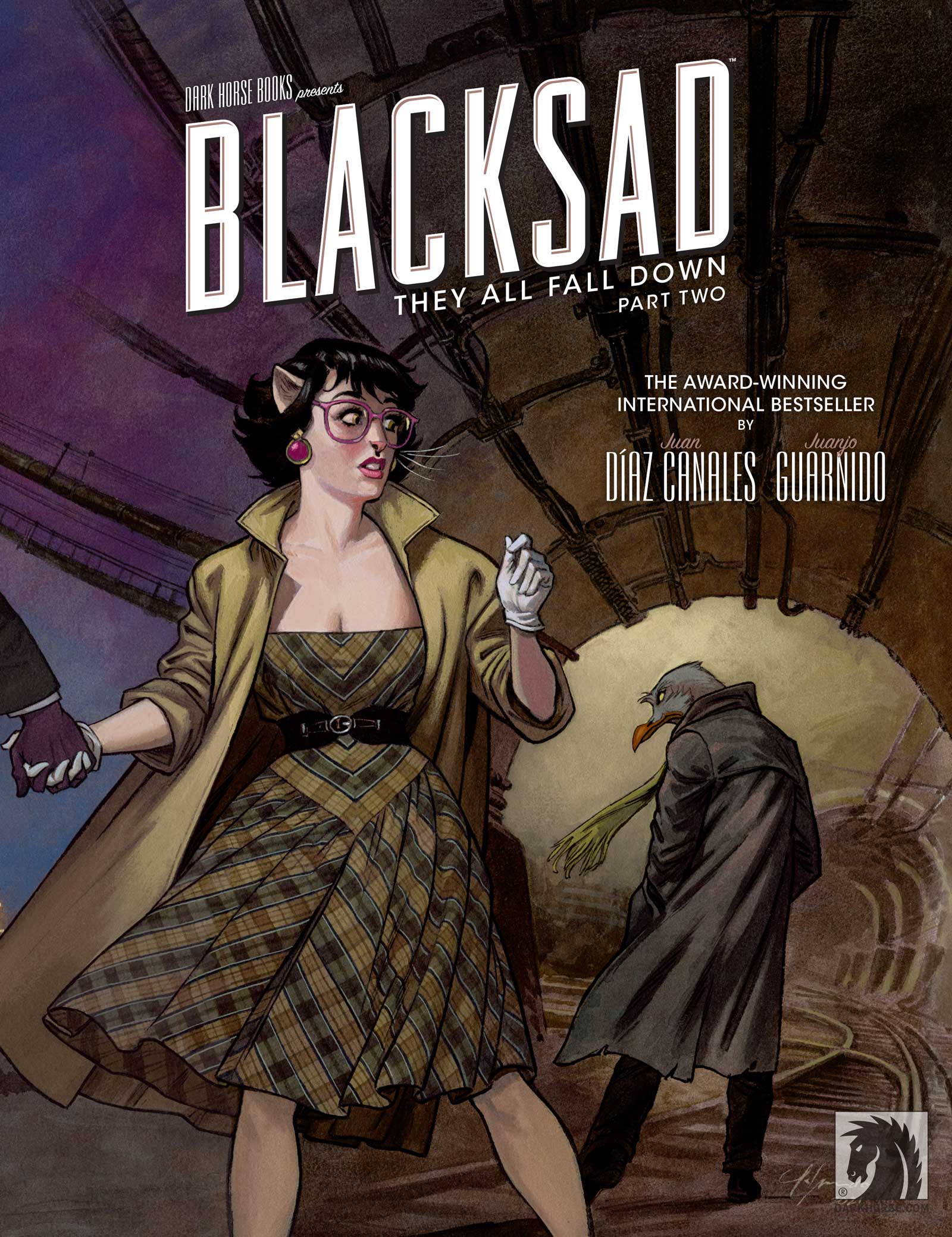

Blacksad: They All Fall Down Part Two

By Juan Díaz Canales (Writer) & Juanjo Guarnido (Artist) | Translated by Diana Schutz, Brandon Kander

ISBN: 978-1506743981

• Buy it from AmazonUK (Affiliate Link) | uk.bookshop.org (Affiliate Link)

The Eisner-and Harvey-winning story begun in Blacksad: They All Fall Down – Part One comes to a thrilling conclusion as private investigator John Blacksad finds himself in a race against time to save his best friend from the electric chair! Weekly’s been framed by Lewis Solomon, the power behind New York’s construction boom, but the king of the hill has built his empire on a mound of corpses, including union attorney Kenneth Clarke and theatre director Iris Allen, and Blacksad must take out their killer before he can take down Solomon.

But with Weekly in stir and cops on his heels, the feline detective is minus an ally – and the sudden reappearance of his lost love Alma promises a dangerous distraction as he seeks to uncover the truth.

The album’s translation into English by Diana Schutz and Brandon Kander has recently been nominated for a Sophie Castille Awards for Comics in Translation – English.

Juanjo Guarnido: The Story So Far…

Award-winning creator Juanjo Guarnido was born in Granada, Spain, in 1967. He spent his childhood drawing, in the town of Salobreña, before moving north to Granada with his family. There, he studied Fine Arts, joined the local fanzines and had some Marvel character illustrations published by Comics Forum. He turned next to animation, moving to Madrid, to work for the Lápiz Azul animation studio.

On his first day at Lápiz Azul, Guarnido met Juan Díaz Canales, who would become his friend and the writer of Blacksad. In 1993, Guarnido moved to Paris to join the Walt Disney Studios in Montreuil, where he moved from layout work (on The Goofy Movie, Mickey’s Runaway Brain, and Hunchback of Notre Dame) to character animation (Hades in Hercules; Tarzan and Sabor in Tarzan; and Helga in Atlantis). Guarnido also contributed to The Jungle Book 2 and Lorenzo the Cat before the French Disney office closed down, ten years after he was first hired.

A longtime fan both of the European bande dessinée market and of American comics, Guarnido patiently began the production of his first graphic album while still at Disney, working long-distance with Díaz Canales toward the 2000 publication of Blacksad: Somewhere within the Shadows. The overwhelming success of the title has allowed Guarnido to take on other projects – like Sorcelleries with writer Teresa Valero – or directing and animating the music video Freak of the Week for the Swedish band Freak Kitchen.

In addition to the Blacksad series, Guarnido spent then three years and a half working on the one-issue, ambitious 145 pages fully watercolour graphic novel Les Indes Fourbes, with script by Alain Ayroles, which hit Europe in autumn 2019 with huge success, and has recently completed.

His most recent accolade was being awarded the 2024 Sergio Aragonés International Award for Excellence in Comic Art by The National Cartoonists Society Foundation, presented at last year’s Lakes International Comic Art Festival.

Categories: Comic Creator Interviews, Creating Comics, downthetubes Comics News, downthetubes News, Features

Bill Watterson: The Interviews

Bill Watterson: The Interviews  Creating Comics: Scripting Spooky Strips

Creating Comics: Scripting Spooky Strips  Bones & Betrayals: A Chat with Andi Ewington, Erica Marks and Calum Alexander Watt

Bones & Betrayals: A Chat with Andi Ewington, Erica Marks and Calum Alexander Watt  Crowdfunding Spotlight : An Interview with Rachael Smith, creator of Nap Comix

Crowdfunding Spotlight : An Interview with Rachael Smith, creator of Nap Comix