Script writer Ray Aspden reveals the secret workings of creating DC Thomson’s fondly-remembered science fiction title, Starblazer…

Jack Smith was the originating editor of DC Thomson’s Space Fiction Adventure Picture Library, in essence a Star Wars variation of the Commando title. Jack had a background in romantic fiction rather than comics and in the event, the title never really took off: he once ruefully told me that it only continued because there was spare capacity on the Thomson’s presses and the loss it made could be offset against company profits.

Distribution was patchy, but Thomsons apparently got rid of the undated backlog by sending them in bulk to seaside towns during the summer holiday months.

Although I had already sold two serials for Victor (only one was ever published – “Stokehold Joe” in Issue 1005 May 24th 1980), I only got to know about the project through a small ad in the Guardian. In return for a s.a.e. Thomsons supplied a brief guide of requirements – basically space adventures with a clean cut hero and lots of gadgets.

In September 1978 I wrote a 750 word synopsis called “The Basilisk: Face of Fear” and had it accepted. The plot was loosely based on Perseus and the Gorgon’s Head, although I found out later that the Editors hadn’t initially realised the connection. The script was written the following month, the cheque followed shortly and it was published in May 1979 as “The Domes of Death” (Starblazer Issue 2).

It’s hard to imagine now, in an age of word processing and ink jet printers, but in 1978 I was using an Imperial portable typewriter. The terms were to produce a top copy for Thomsons, a carbon copy for the artist (the denizens of Dundee did not spend money on photocopying if they could avoid it!) and an optional carbon copy for my file.

I got £95 for 48 pages of double spaced typing. In 1978 that would have meant selling one a week to gross an income equivalent to my then day job. An impossible ambition both from the point of view of the market and my own imagination. Starblazermoney subsequently went towards the purchase of a “tax deductible” electric typewriter, with no memory but the benefits of an even key-strike!

Thomsons asked for more ideas, which was something of a new experience for me. My next was a reworking of Theseus and the Minotaur which saw print as Sinister City. The hero was Redd Dexter – I was never sure if Thomsons twigged the heraldic terminology. I can’t remember whether I left Ariadne out on instinct or instruction – women are few and far between in Starblazer. I got the cheque for “Sinister City” in January 1979 and it appeared as Starblazer Issue 19. The third one I sold didn’t appear until Starblazer Issue 123 – I think the script got overlooked in an artist’s studio somewhere.

A reworking of “Sparky and his Magic Piano” under the title “Sounds of the Spheres” didn’t appeal but other ideas did. Thus a pattern was set. Some story outlines were accepted, either at once or after amendment, and several were rejected. On average I sold one in three at a rate of four a year, but I was often able to cannibalise the rejected material.

The Dundee editors travelled the country to keep in touch with contributors. In May 1979 I had the first of several meetings with Jack Smith at the Bedford Hotel in Bloomsbury, London. On this occasion his young deputy Bill McLoughlin was with him. They were kind and appreciative without actually going into detail or making promises. They recognised that rejection slips led to personal paranoia and that the money was disproportionate to the time it took to produce the scripts, and so took pains to jolly their writers along.

The Thomsons London office was no more than a mail drop – useful for saving postage on bulky scripts going north. There is the story of a newly arrived Australian artist taking his portfolio to Fleet Street and being told by the doorman, “The editors are all in Dundee” to which he replied, “I don’t mind waiting!” – thinking that Dundee was where they went for lunch!

One of Starblazer‘s ploys was to send me cover pictures they’d bought from art agencies and ask for stories which might go with them. Issue 62 – “Terror Tomb” – was one, which I originally wrote as “The Planeteers of the R10″. I also trawled books of science fiction art and SF encyclopaedias in a never ending quest for ideas. The stories didn’t automatically sell and even when they did the inspiring cover wasn’t always used, or had been used elsewhere.

Jack said he was always keen to use British artists. He was in touch with Temple Arts who would show him recent portfolios. I guess however that currency exchange rates got them a better deal with foreign based artists. The detail in some of the artwork is way beyond what DCT could reasonably expect for their picture library page rate.

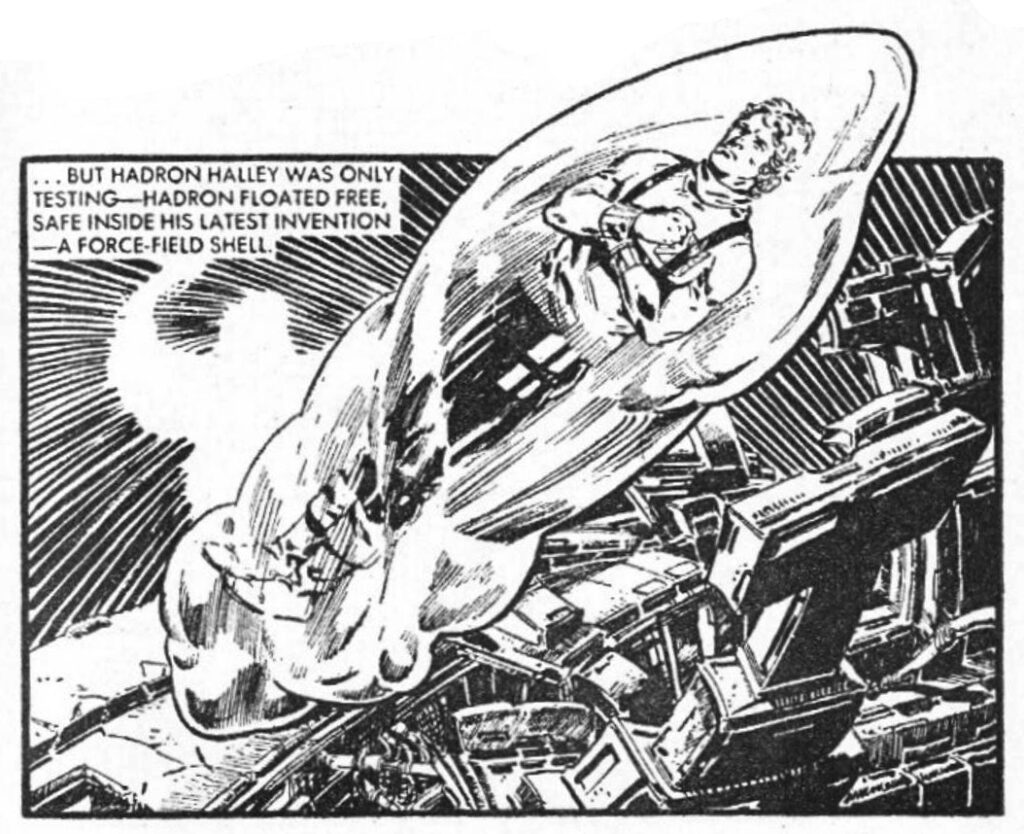

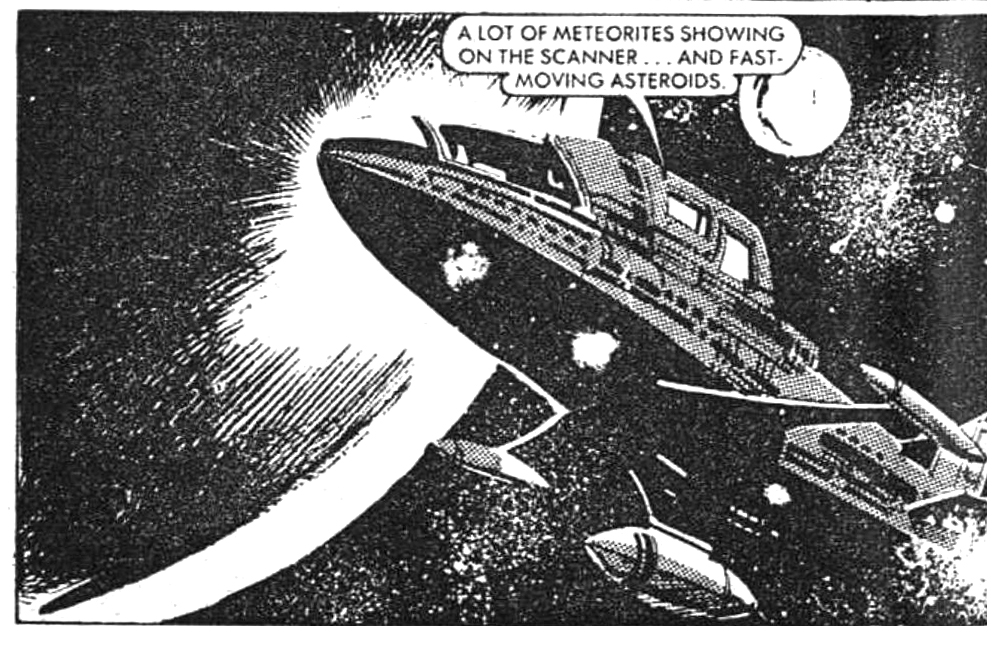

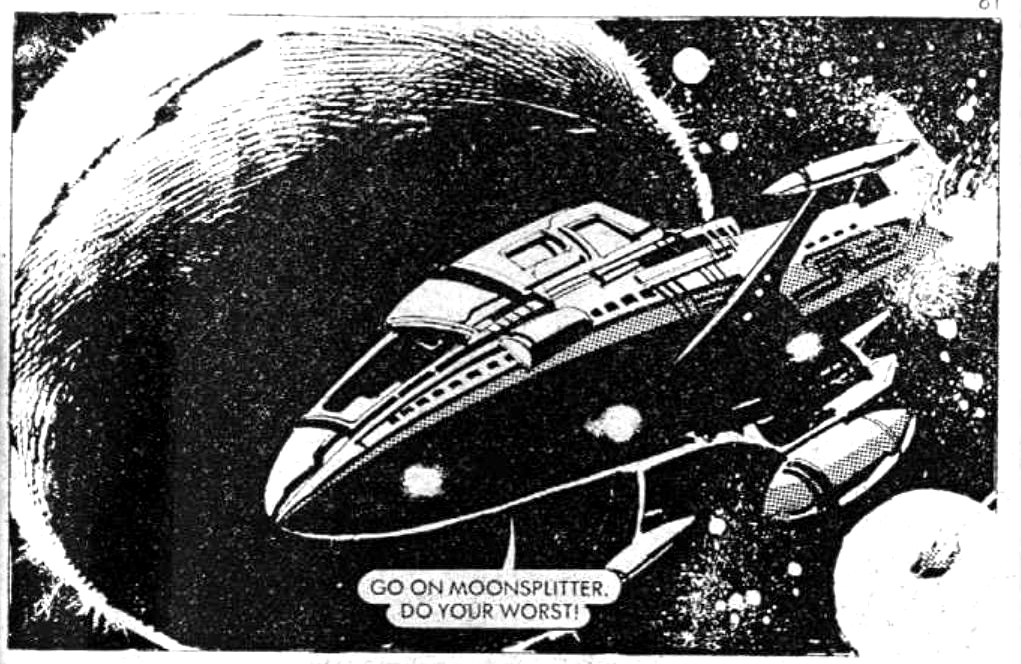

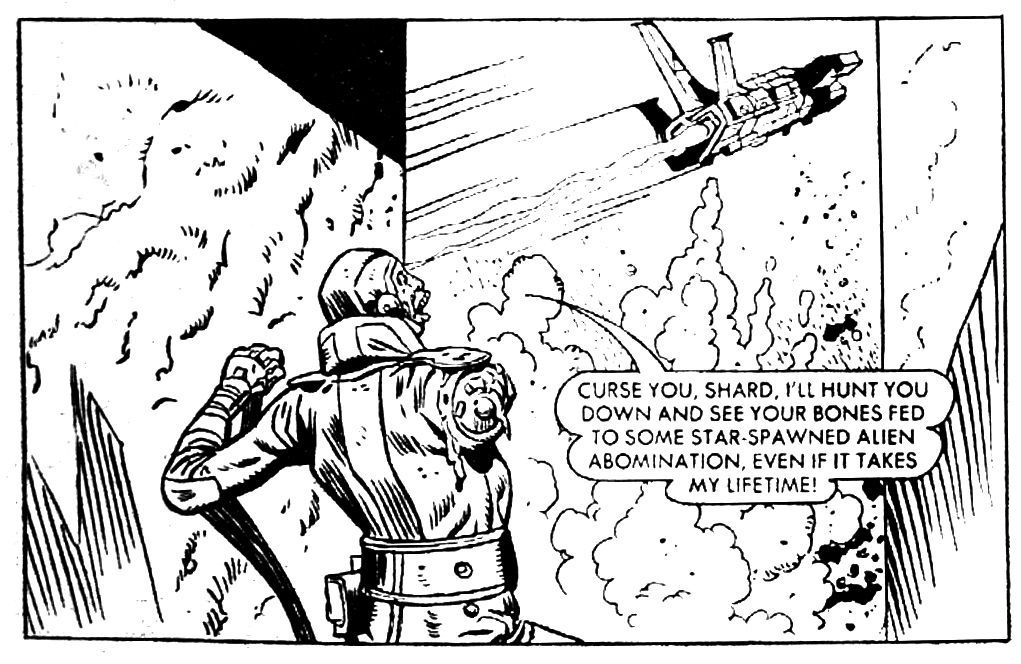

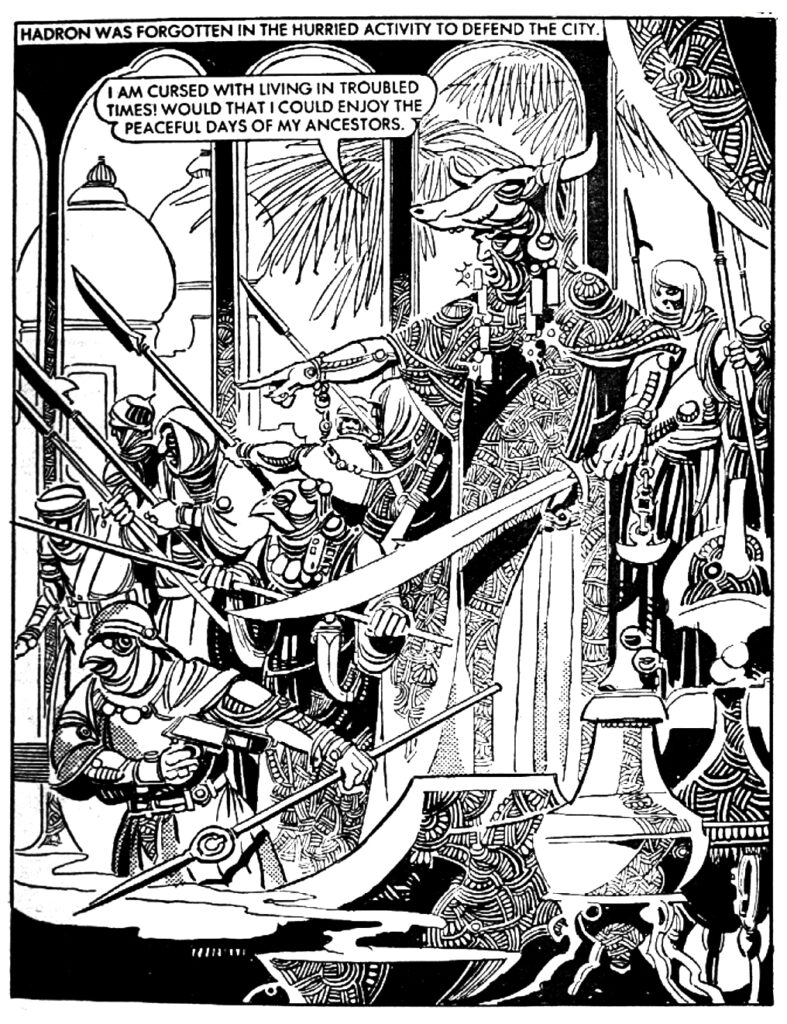

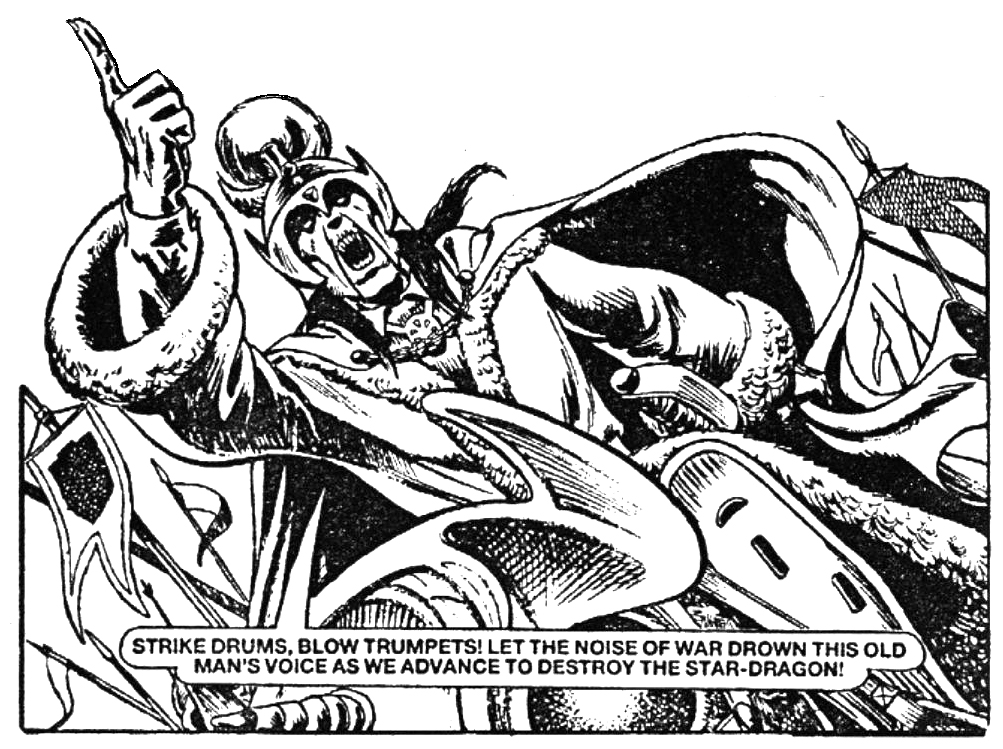

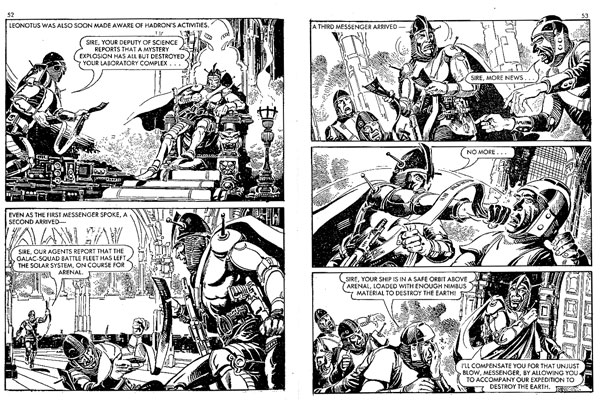

One of my ploys was to always leave a storyline capable of having a sequel. In the event, the only character which achieved this was Hadron Halle, the man from Fi-Sciy. The forename came from a book on sub-atomic particles. Jack had come up with the idea that the reverse of Sci-Fi could stand for Fighting Scientist. I developed Moonsplitter, where the rational scientific approach of Hadron would contrast with the gung-ho militarism of General Larz Pluto. Unfortunately the thing was badly illustrated. The artist used several copies of frames he’d used in a previous issue of Starblazer, which seriously disrupted the continuity. Young Willie also did his customary hatchet job on my dialogue. For instance the first appearance of General Larz has him saying, “Sector 7 no.2 – increase elevation” instead of the “Once more unto the breech, Galac Squad!” which I wrote. In trying to make Larz Pluto a buffoon I had transgressed Thomsons moral code of wanting figures of authority to be seen as worthy of respect. The end result was a mess.

I can’t say I was ever fond of Hadron, even though subsequent appearances were better drawn and better subbed. The Man from Fi-Sci never felt like mine, even though he was. I think the later stories featuring him would have sold whatever the name of the hero.

One thing I am happy to claim credit for is originating Jupe, short for Jupiter, as an acceptable expletive; on a par with Drokk in 2000AD.

Due to the childhood influence of Eagle I tried to have character driving the plot and the nuances of character revealed in the dialogue. Jack and Bill however wanted action and gadgets. They also imposed a word limitation on speech bubbles and had total control over the ultimately published dialogue. As a result many Starblazers based on my scripts have the characters making bland statements of the bleeding obvious, instead of the witty one-liners I originally gave them. I used to complain regularly. I think Jack understood that it was nothing personal and told me I shouldn’t care so passionately about my creations. His advice was to completely forget about a script once I’d had the cheque and make a start on the next idea.

Bill was probably more affected by my moans, being the one who was actually doing the subbing. I regularly accused him of dumbing down. In one of the stories (“The Last Battleground”, Issue 114) he started out by altering the name of the alien villain (Thanos), forgot what he was doing half way thorough and reverted to the name (Pyrax) I’d used in the script. Had I known he was going to be the Starblazer editor after Jack retired, I might not have rubbed his nose in the error quite so much.

Although my weaponry and gadgets were fantastic, I always tried to have a pseudo scientific explanation. These explanations were often too long for the editorial policy on speech bubbles and captions. My deathless prose therefore either got mangled or reduced to something akin to, “With one blast our hero was free”. In Pirates of the Ether Sea (No.100) our hero is adrift in space in a detached gun turret. Bill’s caption reads, “Normally the recoil was absorbed by the force shield of the turret’s parent ship, but in the vacuum of space the recoil acted as a source of equal and opposite reaction.” This is scientific mumbo-jumbo and should have read something like, “To every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. The recoil from the guns, normally absorbed by the force shield of the parent ship, therefore propelled the turret though the vacuum of space.”

Perversely, I don’t see comics as a visual medium. The script should read independently of the pictures, like a radio play. The visuals supply the equivalent of the emotion of the actor’s voice and the scene setting sound effects, but should not be relied upon for continuity.

Because of late trains to Luton and my capacity for ale, it became traditional for me to meet Jack during his visits to London at 6.30 p.m. and go on a pub crawl. On one of these he told me about the hiatus at Thomsons during the 1982 Falklands War. The embargo on trade with Argentina had caught one of their key artists and he had to hastily relocate his studio to Uruguay. I thought it would make a good story for Commando to have Thatcher’s Task Force in pursuit of “Argies” smuggling Starblazer art boards across the River Plate to Montevideo and Jack and I being unmasked as the shadowy UK gang masters!

For the record, I always bought my round on our walkabouts; mainly because I saw the pain it caused a Scotsman to pay London prices. Towards closing time on one of our perambulations round the watering holes of Holborn, Jack once said, “Ray, you’re the best writer we’ve got!” There was a pause while I preened my ego, then Jack punctured my conciet by adding, “All the others would have gone home by now!” I suppose I should have been flattered that my company was more fun for Jack than sitting in a hotel room filling out his expenses claim.

Jack was good company, although it was always difficult to keep him on the subject of comics. Rugby was his passion if I remember rightly. Bill was a golf addict.

I wrote, at their suggestion, two role playing game scripts. One was published, the other never used, as they soon realised what a turkey the idea was. I think they sent me a paperback as an example and I soon worked out that they were based on the logical decision trees we used at work. I tried to introduce loops so that very little of the artwork would be missed, but it would have been better as text with drop in illustrations rather than all pictures.

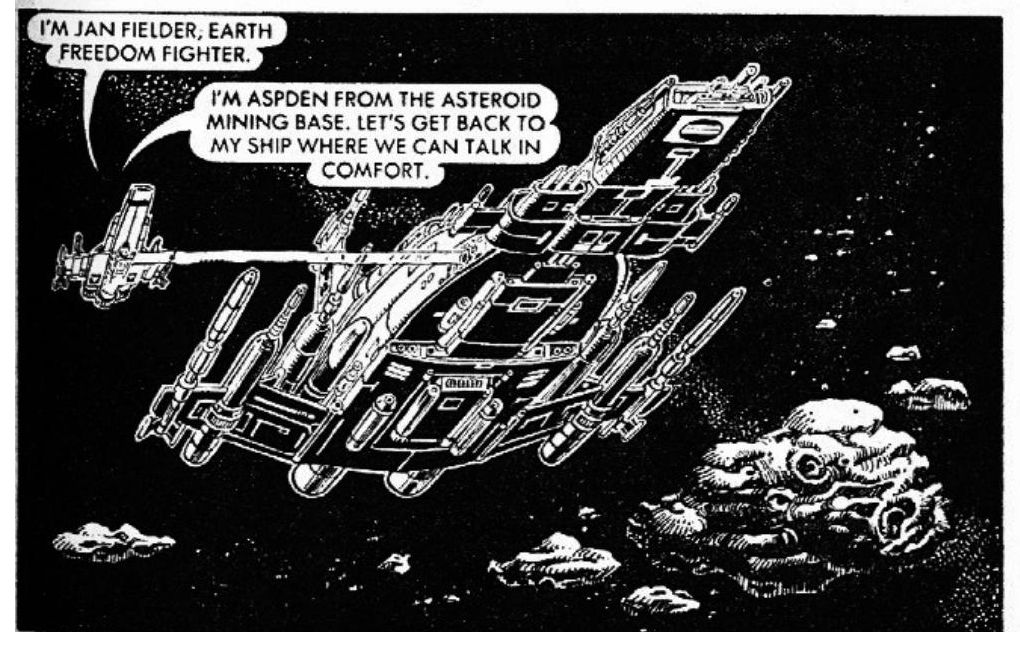

One of the first things DCT did when getting a script with strange alien names in it, was to try and spot if they were anagrams of dirty words – apparently the hit rate was quite high. They obviously spotted the planet Denspa (Aspden) in “Caves of Crystal Carbon” (Issue 145), but let it through. In “Vassals Revenge” (Issue 130) the planet Notul is Luton backwards and in “The Clone Ranger” (Issue 166) the Research Lab at Notrop is Porton (Down) backwards. The “evil warlord Raspden” in “Laser Sword” (Issue 170) was Bill’s doing, as was “Aspden from the Asteroid” in “The Freedom Fighters” (Issue 118). I think they look stupid, but I suppose it served me right for complaining about anonymity!

For reasons of vanity I would have liked my name on the cover, but wouldn’t have wanted posterity to judge me by the published contents. Thomsons policy on anonymity was probably driven by their accountants – they didn’t want to risk a claim for royalties. Jack’s attitude was that, because he and I and Bill and the artist were all involved in the production process, at the end of the day who could say who’s story it actually was. He had a point. The Editors imposed a house style and I couldn’t now pick up a random Starblazer and know for sure whether I’d once written it or not.

Part way though the series they issued a list of clichés which had been done to death and were henceforth forbidden. Among other scenarios: heroes were not to escape through air-conditioning ducts; they were not to knock guards on the head and steal their uniforms as a disguise, and they were not to be condemned to conflict in an arena.

By 1986, I’d sold them 31 scripts (only 27, as far as I know, were published) and was still only as good as my next synopsis. It was irritating to be told ideas weren’t up to my usual standard when I thought I had a track record of producing workable stories. The main problem however was that I didn’t feel my writing was developing. It sounded like a joke, but it wasn’t, when I told people I’d sold the same story 31 times. In some ways I was lucky, because the closure of Victor, Hotspur, Hornetand Wizard had left many more established DCT writers than I, without work. I was arrogant (I still am arrogant) and felt frustrated by not having any contact with the artists, no control over the published dialogue and no licence to write beyond their formula.

Bill McLoughlin made policy changes when he became editor in 1986. Instead of a storyline synopsis he wanted the first ten frames to judge a story by. This approach went against my old fashioned understanding that a plot should have an integrated beginning, middle and end. He moved from Space Fiction to Fantasy and I never really got a handle on what he saw as the difference. The last thing I sold was Laser Sword (No.170) in June 1986 (two earlier scripts were published after this) and the last thing he rejected was a pastiche on the Arabian Nights in October 1986. We never formally said goodbye; I just stopped sending him stuff and he never wrote to ask why.

In retrospect, I think my practical reason for opting out when I did was that I had an increasingly demanding, well paid, day job, as well as other low paid freelance strip work, and wasn’t getting out much!

Ray Aspden – June 2006

This page is part of our Starblazer section on downthetubes

• Click Here for Jeremy Briggs article on Starblazer: Blazing Through the Secrecy

Jeremy Briggs ponders DC Thomson’s secretive nature about its creators down the years, and explores the secrets of its science fiction title Starblazer, whose creators included a young Grant Morrison and artist Ian Kennedy…

• Click Here for From the Command Deck: Starblazer editor Bill McLoughlin’s history of the title

• Click Here for Starblazer Ray Aspden’s feature on writing for the title

• Click Here for Starblazer Recalled: Forgotten Fantasy Fiction – With Pictures by series writer Mike Chinn

• Click Here for a complete Starblazer Cover Gallery (off site)

Cover scans for these Starblazer articles with thanks to ‘Gary’

Starblazer Checklist

Issues 1 – 75 | Issues 76 – 150 | Issues 151 – 200 | Issues 201 – 250 | Issues 251 – 281 | Starblazer Abroad

External Links

• Fish 1000 Comics: Grant Morrison’s Starblazer work

• Vic Whittle’s Starblazer Page

Steve Holland is amazed at how many people remember Starblazer, noting the pocket books appeared as “regular as clockwork throughout the 1980s at the rate of two new titles a month so I guess over the nearly twelve years it appeared a vast army of young science fiction fans, high on Star Wars or Battlestar Galactica, sought them out.”

Starblazer fan Douglas Nicol began this article on the internet’s contributor-based encyclopedia

This article is © 2006 Ray Aspden and must not be reprinted without his express permission. Starblazer is © DC Thomson. The images featured in this article are done so for review purposes only and no copyright infringement is intended.

Leave a Reply