Before there was Game of Thrones, Star Wars or even Star Trek, there was Dune, now the biggest selling science fiction novel of all time. With a new film out here on 22nd October, Chris Hallam takes a look at Frank Herbert’s epic sci-fi saga of sun, sandworms, stillsuits and spice…

The Riddle of the Sands

“Arrakis … Dune … wasteland of the Empire, and the most valuable planet in the universe. Because it is here — and only here — where spice is found. The spice. Without it there is no commerce in the Empire, there is no civilization. Arrakis … Dune … home of the spice, greatest of treasure in the universe. And he who controls it, controls our destiny.” Frank Herbert – Dune (1965)

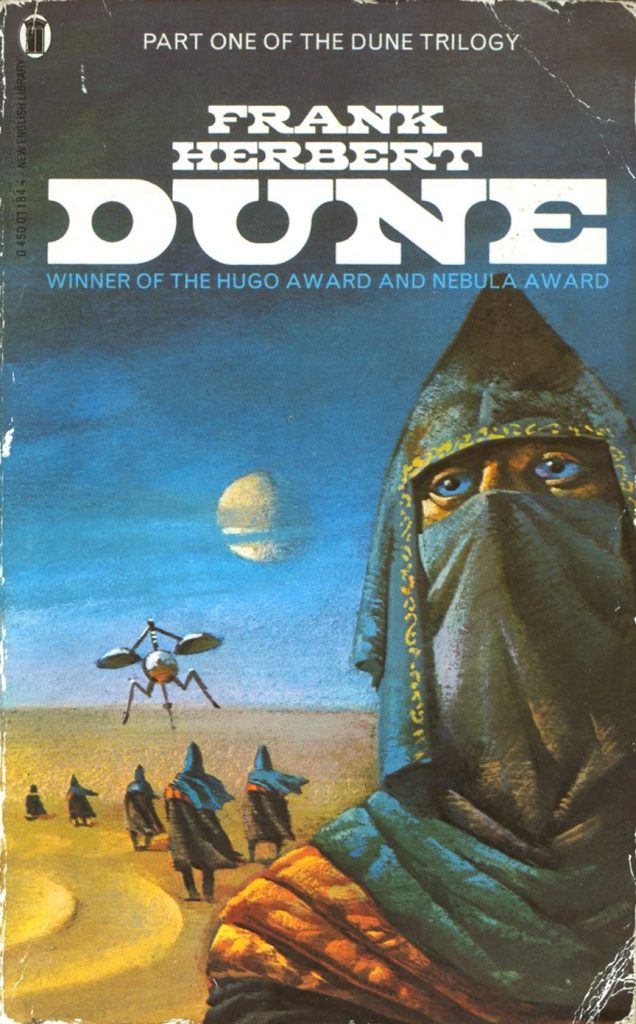

In 1965, a new book introduced readers to a world they had never seen before.

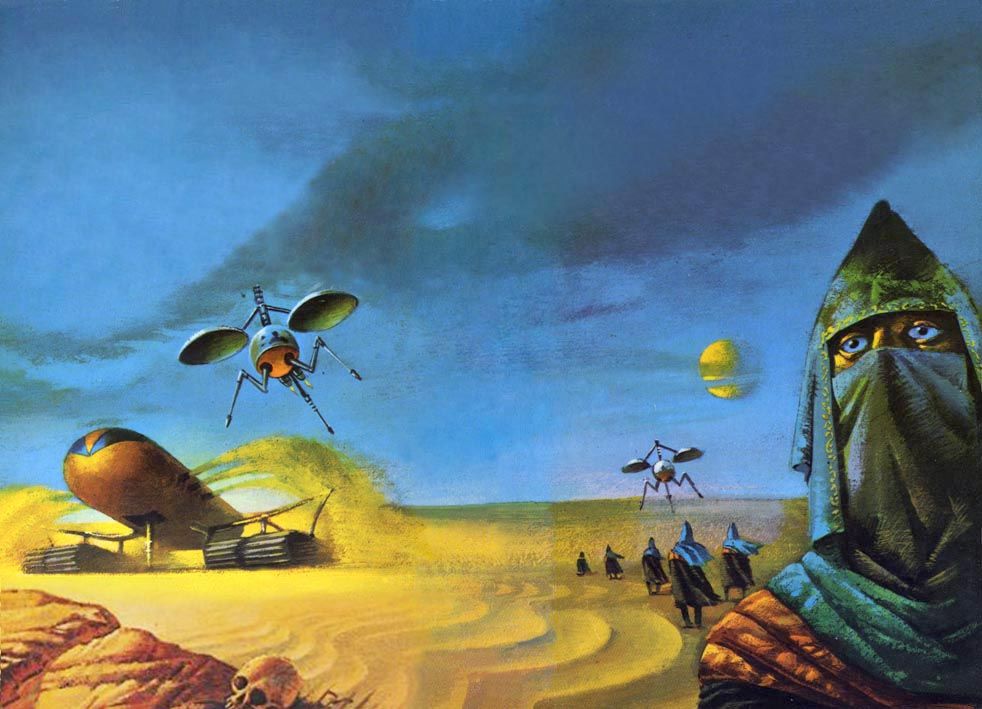

The novel was Dune, written by US author, Frank Herbert. Dune was also the alternative name for Arrakis, the desert planet on which most of the story’s action was set. An inhospitable desert world, the planet’s main inhabitants are the Fremen, a seemingly primitive culture, who can only travel across their world using stillsuits; special body suits designed to help preserve the body’s moisture.

But dehydration is only one of the perils endangering Arrakis’s inhabitants. For the main focus of the novel is the battle for ‘spice’ between the external feudal powers who seek to win control of Arrakis. Our sympathies lie with young Paul Atreides, the son and heir of a family engaged in a bitter power struggle with the House Harkonnen for the planet’s precious spice reserves. For this is no ordinary spice, but a rare resource unique to Arrakis which (amongst other things) enables interplanetary travel.

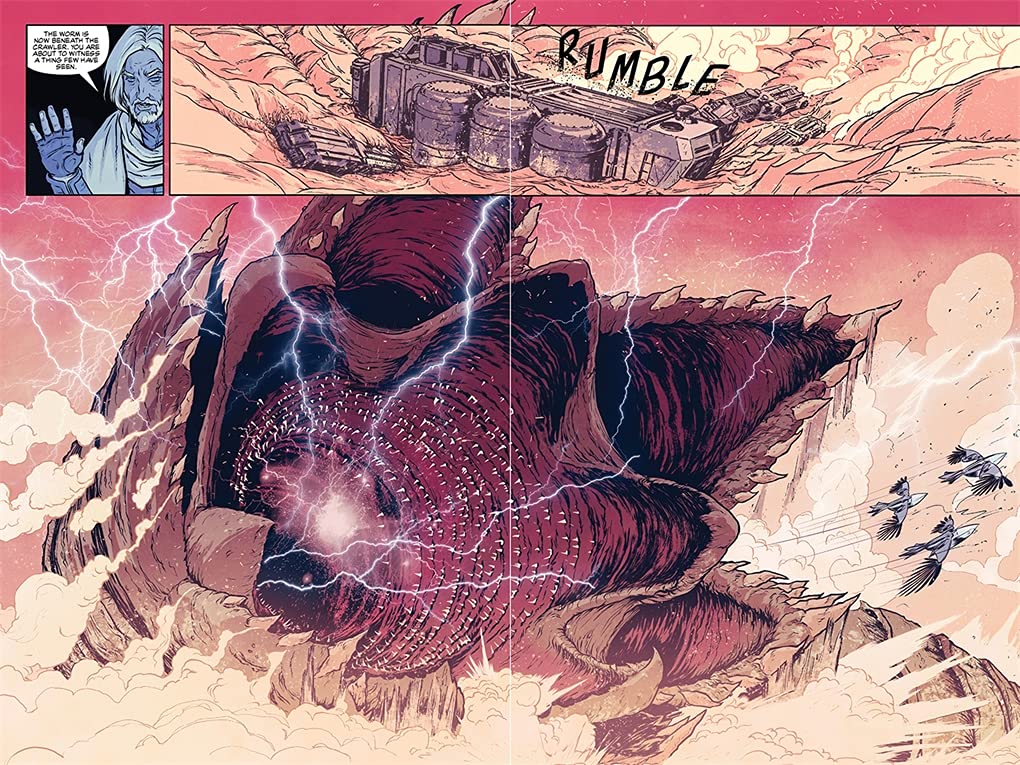

All this comes before we even mention the book’s most haunting creations, the vast, awe-inspiring Sandworms who roam Arrakis occasionally breaking cover with often devastating results.

And detailed as the summary might sound, those of you who have read the novel will know that unlike the majestic Sandworms, it scarcely scratches the surface of the mighty world of Dune itself.

A World of His Own

Dune has become, according to many, the bestselling science fiction novel of all time. Absorbing, complex, full of characters, events and intrigue, it has been critically acclaimed and prompted creator Frank Herbert to produce five sequels in the twenty years after it was published in 1965. Since Herbert’s death in 1986, the number of published Dune novels has risen to nearly twenty.

There have also been a number of short stories, comic adaptations, an early 21st century TV series, and one notable, though largely unsuccessful, 1980s film version, before the new film released this week.

The original Dune was not, however, originally intended to be a novel at all.

In 1957, Herbert, who was then in his thirties began writing an article about a real-life government experiment to deploy poverty grasses to prevent the development of damaging sand dunes which might potentially swallow up roads, rivers and homes. Already an aspiring science fiction writer, however, Herbert never finished the non-fiction article, which instead evolved into a version of the story we know of as Dune.

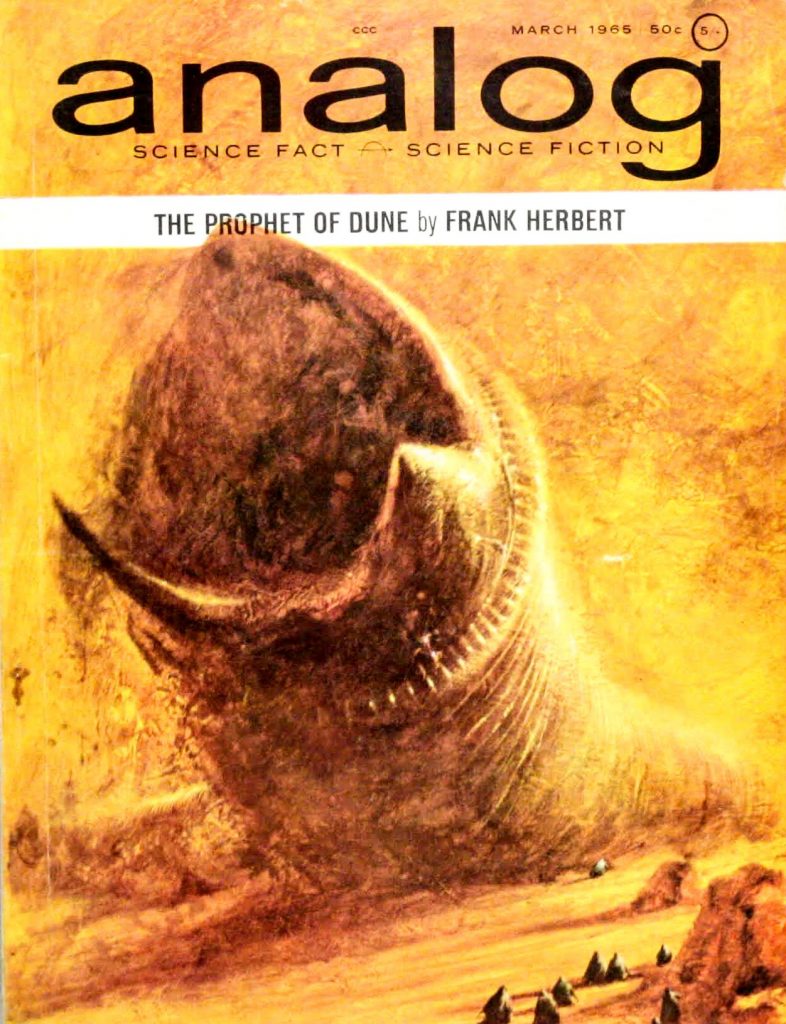

The end result appeared in sci-fi magazine, Analog in 1963 and 1965, in two parts comprising eight instalments: “Dune World” and “Prophet of Dune”. But even at this stage, there were concerns about Dune’s length. The novel was rejected by over twenty publishers and was substantially re-written before finally being published in 1965. The final version is around 175,000 words: a similar wordcount to J.R.R. Tolkien’s first Lord of the Rings book, The Fellowship of the Ring.

Massive success was not immediate. Reviews were good and the book won the Nebula Prize for Best Novel in 1965 and shared the Hugo Award in 1966. Sales were good too, but Herbert did not feel able to give up his day job in the newspaper industry until the early 1970s.

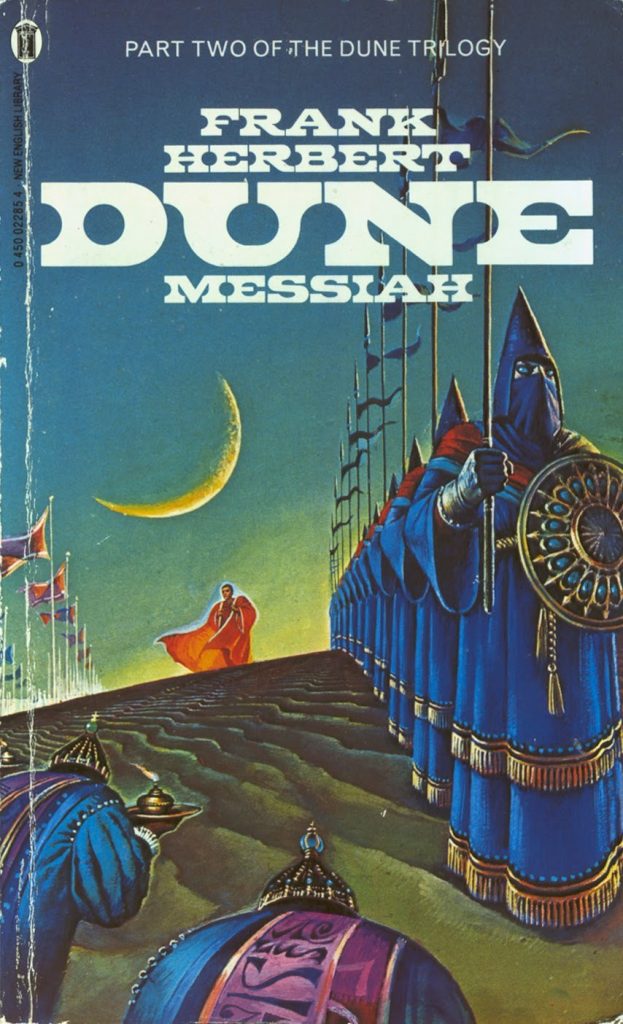

By this time, Herbert had produced the first sequel to Dune, Dune Messiah, in 1969.

He had also sold the film rights.

The Worm That Turned

It was probably inevitable that some attempt would be made to film Dune. With the novel so vast and complicated, it was also inevitable that it would not be an easy task.

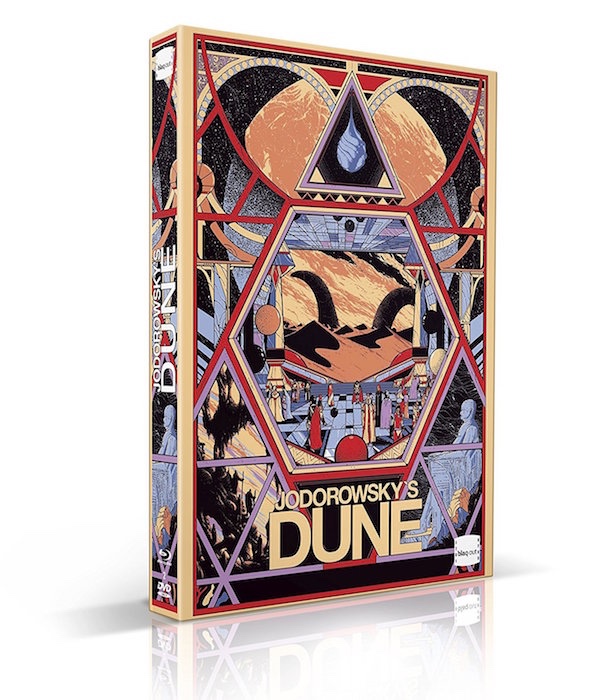

Herbert first sold the movie rights in 1971. They were sold on again in 1973. Leading Chilean filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky began a hugely ambitious adaptation which planned to incorporate the talents of Peter Gabriel and Pink Floyd, design work by H.R. Giger and a cast including Orson Welles, silent screen star Gloria Swanson and (bizarrely) artist, Salvador Dali.

With a script said to be long enough for a film lasting 14 hours and millions already spent, the production fell apart. A documentary about it, Jodorowsky’s Dune was released in 2014. It can be viewed today on YouTube.

In 1976, Herbert’s third Dune novel, Children of Dune, appeared. In the same year, legendary producer Dino De Laurentiis bought the rights to the original and commissioned a screenplay from Frank Herbert himself. Once again, the screenplay was much too long to use. De Laurentiis hired novelist Rudy Wurlitzer to write a script instead in 1979. British director Ridley Scott began to direct it, before abandoning it seven months later as he wanted to direct Blade Runner instead.

It was at this point that Dino’s daughter Raffaella suggested David Lynch was the man to bring Dune to the screen.

Then in his thirties, Lynch was a very hot property having directed the attention-grabbing oddity, Eraserhead and followed it up with The Elephant Man. Despite this, he was in some ways an odd choice for Dune, simply because he had no interest in science fiction at all. He had recently turned down an offer to direct Return of the Jedi, developing a thumping headache during a meeting with George Lucas.

Furthermore, he had never heard of Dune at all. When Dino De Laurentiis started discussing the project with him, Lynch initially thought he was talking about something called ‘June.’

A World Beyond Your Experience. Beyond Your Imagination

Lynch wrote five drafts of the script, eventually producing a final version which was 135 pages long.

Filming began March 1983 with a budget of 40 million dollars and 1,700 people on the cast and crew. Shot in Mexico in 120-degree heat, four camera units worked simultaneously on 80 sets that filled eight soundstages. Lynch was not Jodorowsky, but this was nevertheless an ambitious project. Lynch often speaks disparagingly of having “sold out” by making Dune. This seems harsh: although he was undeniably well-paid, he also worked very hard. In fairness, he also probably did not see himself as selling out at the time.

The film featured an impressive cast. In the central roles of Lady Jessica and her son, Paul, Lynch cast British actress Francesca Annis and a young American actor, Kyle MacLachlan. Though playing a teenager, MacLachlan was well into his twenties and in fact, less than fourteen years younger than his onscreen mother. The film saw MacLachlan develop a strong friendship with Lynch which continues off and on screen to this day.

Other cast members included veteran actor Freddie Jones (the father of Toby) as the aged Thufir Hawat, Flash Gordon villain and veteran, Max von Sydow, Blade Runner’s Sean Young and future Quantum Leap star, Dean Stockwell as “Don’t trust me, I’m a doctor” Wellington Yeuh.

Much attention focused on the casting of musician Sting in his fifth film role, as the murderous Feyd Rauta. For his first appearance in the film, Sting was required to appear, surrounded by steam, wearing only a pair of rubber underpants. Sting did so, but only after some extensive persuasion from his director.

There was some confusion. Future Star Trek and X-Men star, Patrick Stewart, who played one-man quote-machine Gurney Halleck, later admitted he had no idea who Sting was. After a brief polite conversation, Stewart came away with the impression Sting was a musician within a band within the police force rather than the lead vocalist of the world-famous group, The Police.

The fun soon wore off. Lynch admits “a year and a half into Dune, I had a feeling of deep horror.” The film seemed to be slipping away from him.

Dino de Laurentiis, who died in 2010, admitted later “we destroyed Dune in the editing room.”

Lynch blames himself. “I always knew Dino had final cut on Dune and because of that I started selling out even before I started filming,” he now says. “It was pathetic is what it was, but it was the only way I could survive, because I signed a fucking contract. A three-picture deal for Dune and two sequels. If it had been a success, I would have been Mr. Dune.”

But the film, released in December 1984, was not a success. It was a critical and box office flop.

Aftershocks

As it turned out, the real ‘Mr. Dune’ was one of the film’s few defenders. “What reached the screen is a visual feast that begins as Dune begins, and you hear my dialogue all through it,” said Frank Herbert. Sci-fi author Harlan Ellison also championed the film.

But others were much less kind. The influential US critic Roger Ebert’s review was typical: “This movie is a real mess, an incomprehensible, ugly, unstructured, pointless excursion into the murkier realms of one of the most confusing screenplays of all time.” He later stated it was “the worst film of the year”. Quite a bold claim, particularly as 1984 was also the year Supergirl came out.

Understandably, people involved in the film’s production have been easier on it.

Kyle MacLachlan admits “ there are just too many things going on in the book” to do it justice on screen bit argues the movie remains “a flawed masterpiece” while Sting concedes: “To cram the whole book into a single feature might have been a mistake, and on the big screen I found it overwhelming, but oddly enough, it holds up on a smaller screen for me”.

Producer and daughter of Dino, Raffaella De Laurentiis concluded: “The biggest mistake we made was trying to be too faithful to the book…we felt like, my God, it’s Dune – how can we f*** around with it? But a movie is different from a book and you have to understand that from the start.”

As it was, following the film’s failure, David Lynch abandoned the screenplay for a Dune sequel he had been working on, moving immediately onto Blue Velvet (also starring MacLachlan and featuring Dean Stockwell) and the acclaimed offbeat films he has become known for.

Frank Herbert’s sixth Dune book, Chapterhouse: Dune appeared in April 1985. It was to be his last. He died in February 1986, aged 65.

Back to the beginning

The six Dune novels continued to sell well throughout the rest of the 20th century. In 1992, the computer game, Dune II not only proved the most popular of a number of Dune computer games, but is now seen as one of the most influential real time strategy games ever made. In 1996, Amiga Power magazine rated it as the 11th best game of all time.

The new millennium witnessed a surge in Dune-related output. Firstly, Frank’s son, Brian Herbert and sci-fi author Kevin J. Anderson teamed up to write a prequel trilogy, known as Prelude to Dune, partly based on notes left by Frank Herbert. This has been followed by a large number of Dune prequels, listed below. It is probably fair to say only a few dedicated fans will ever read them all.

2000 and 2003 also saw two Sci-Fi channel TV series, Frank Herbert’s Dune and Frank Herbert’s Children of Dune with a cast including Alec Newman and Oscar winner, William Hurt. Both were generally well received, though many were left with the feeling that the definitive screen version of Dune was still yet to come.

Soon, after several more aborted attempts we will finally get to see the new film Dune directed by Denis Villeneuve, the man who successfully provided a follow-up to Blade Runner. With a cast including Timothée Chalamet (as Paul), Oscar Isaac as Duke Leto, Jason Momoa as Duncan Idaho and Stellan Skarsgård as the villainous Baron Harkonnen, hopes are high that Villeneuve can overcome the obstacles which have bedevilled adaptations of the franchise in the past.

Fittingly, the film’s release comes just one year after the centenary of Dune’s creator, Frank Herbert.

Chris Hallam

• Chris is online at chrishallamworldview.online

The original Dune novels by Frank Herbert (1920-1986)

Dune (1965)

Dune Messiah (1969)

Children of Dune (1976)

God Emperor of Dune (1981)

Heretics of Dune (1984)

Chapterhouse Dune (1985)

• Dune books on AmazonUK (Affiliate Link)

The Road to Dune (2006)

Features the unpublished chapters and scenes from the original Dune books; as well as correspondence with Frank Herbert relating to Dune; short stories by Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson and, also, “Spice Planet”, an original novella by Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson, based on a detailed outline left by Frank Herbert.

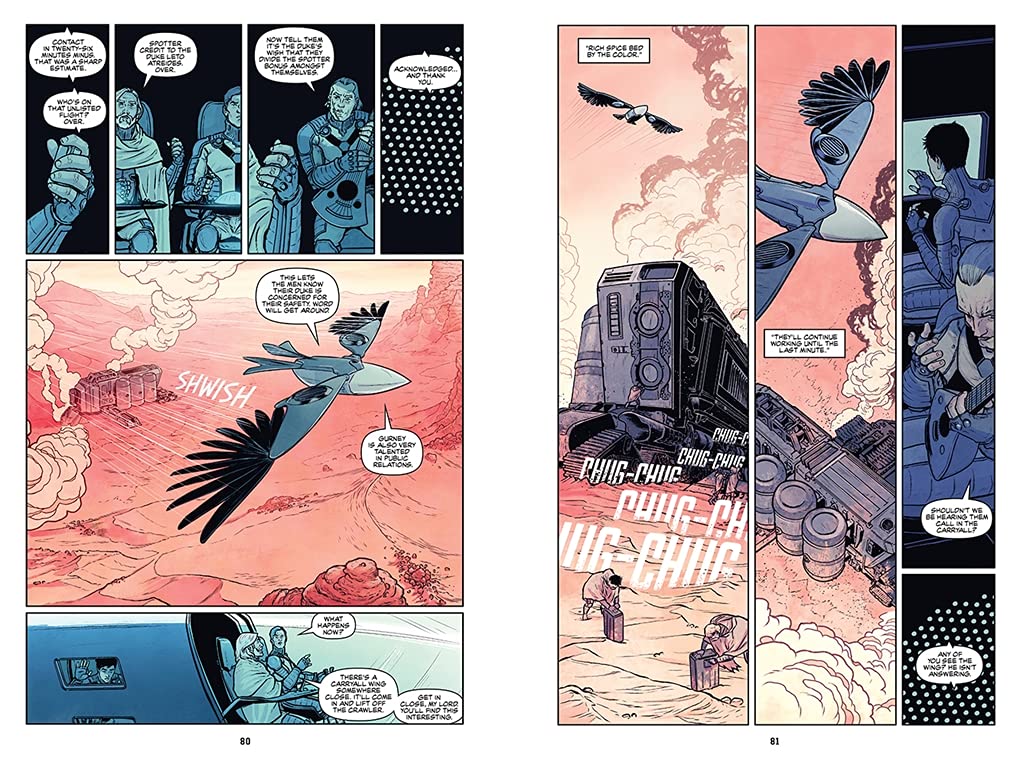

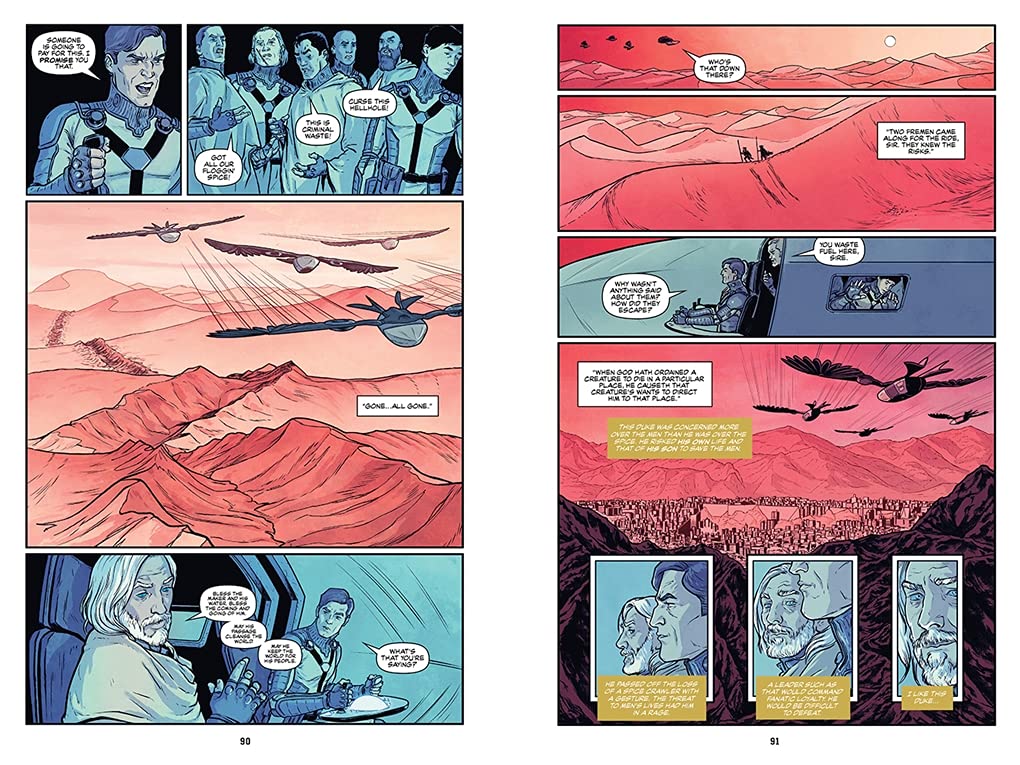

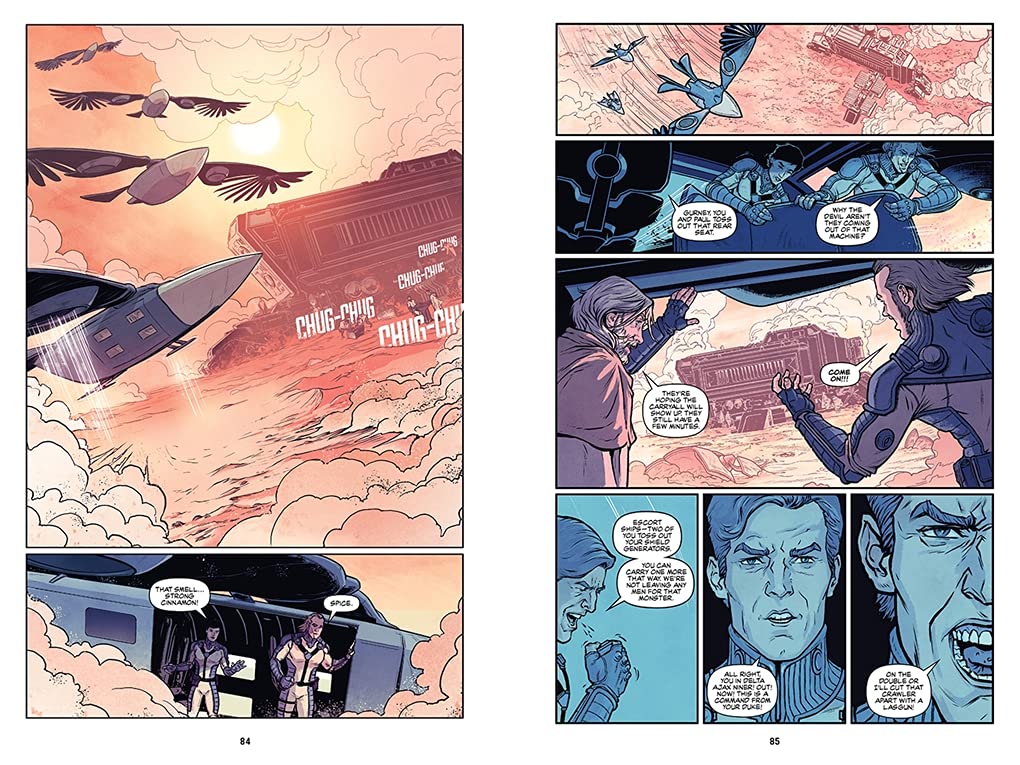

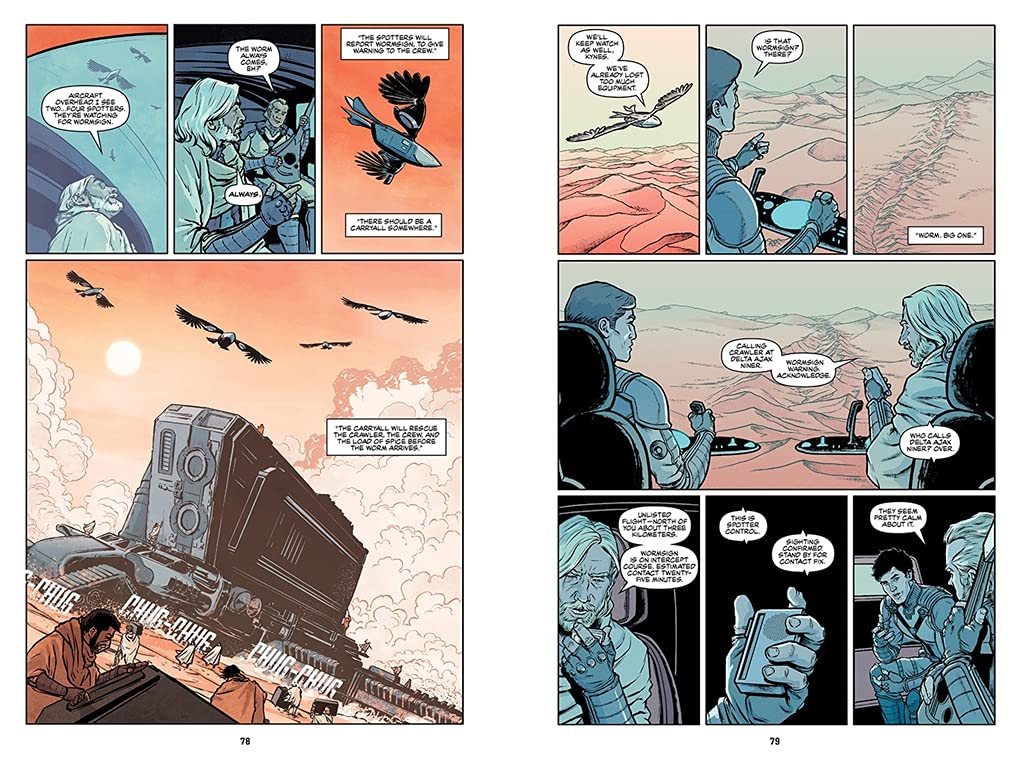

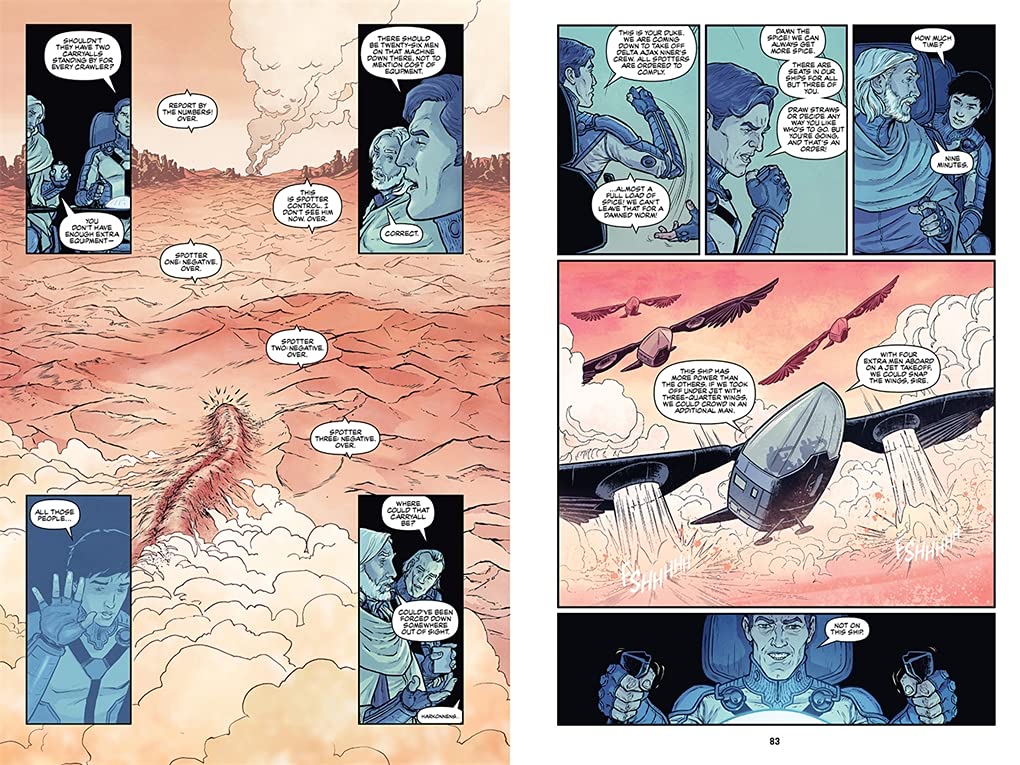

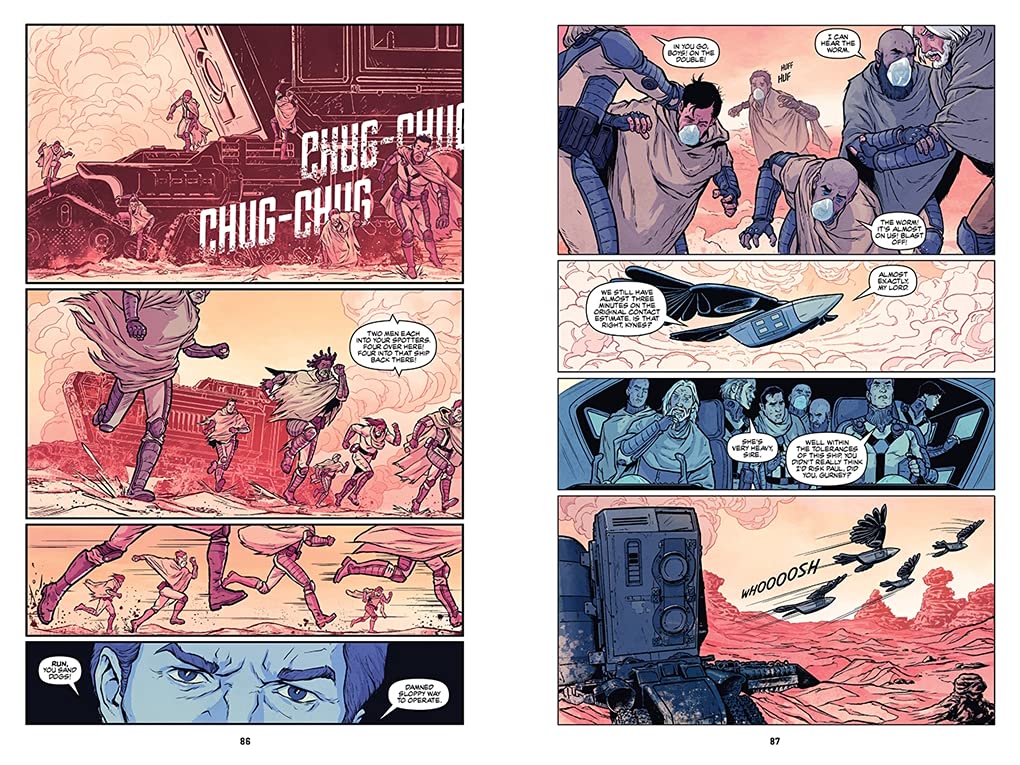

DUNE: The Graphic Novel, Book 1 (2020)

Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson’s adaptation retains the integrity of the original novel, with art by Raúl Allén and Patricia Martín, and cover by Bill Sienkiewicz

Dune prequels by Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson

Prelude to Dune trilogy:

When is it set? just before Dune

Dune: House Atreides (1999)

Dune: House Harkonnen (2000)

Dune: House Corrino (2001)

• Dune books on AmazonUK (Affiliate Link)

Legends of Dune trilogy

When is it set? around 10,000 years before Dune

The Butlerian Jihad (2002)

The Machine Crusade (2003)

The Battle of Corrin (2004)

• Dune books on AmazonUK (Affiliate Link)

Heroes of Dune series:

When is it set? Er…between some of the first six books.

Paul of Dune (2008)

The Winds of Dune (2009)

Great Schools of Dune series:

When is it set? About 100 years after the end of Legends of Dune. Got it?

Sisterhood of Dune (2012)

Mentats of Dune (2014)

Navigators of Dune (2016)

• Dune books on AmazonUK (Affiliate Link)

Web Links

Dune – Behind the Scenes includes everything you want to know about the Dune universe, from Jodorowsky, Lynch, the TV miniseries to the new movie by Denis Villeneuve.

• Dune books – a full release guide on Biblio

• The curse of Dune: a personal history of an orphaned sci-fi epic

GQ examines how a family saga set on a distant planet still feels very close to home

• This is the cover of the French edition of Jodorowsky’s Dune (Collector’s Edition w/ BD, DVD & Book). Directed by Frank Pavich. Cover by Swedish illustrator Killian Eng. The story of cult film director Alejandro Jodorowsky’s ambitious but ultimately doomed film adaptation of the seminal science fiction novel. Limited to 2500 copies, includes BD, DVD, Book, Poster and four Artcards. Available on Blu-Ray and DVD. France released, Blu-Ray/Region B DVD: LANGUAGES: English ( Dolby Digital 2.0 ), English ( DTS 5.1 ), English ( DTS-HD Master Audio ), French ( Subtitles ), WIDESCREEN (1.78:1), SPECIAL FEATURES: 2-DVD Set, Alternative Footage, Blu-Ray & DVD Combo, Booklet, Cast/Crew Interview(s), Collectors Edition, Deleted Scenes, Interactive Menu, Posters, Scene Access, first screened at the Cannes Film Festival

Thanks to Chris Hallam for this feature

One of many guest posts for downthetubes.

Categories: Books, downthetubes News, Film, Other Worlds, Television

Journey Planet nominated for Hugo Award for Best Fanzine

Journey Planet nominated for Hugo Award for Best Fanzine  The Decades that Scarred for Life – now offered at a discount!

The Decades that Scarred for Life – now offered at a discount!  From the Trenches and in Pictures: London Film and Comic Con 2022

From the Trenches and in Pictures: London Film and Comic Con 2022  New edition of Filmed in Supermarionation released

New edition of Filmed in Supermarionation released