Saturday, October 23 1976 must have seemed a pretty ordinary day when it began. A bit cloudy, not too bad, but like any Saturday it meant, for thousands of kids, heading for the local newsagents to buy their copy of the world’s newest and greatest comic – Action, But when they got there, October 23 was definitely no longer just an ordinary day. There was no Action -and didn’t the newsagent look pleased about it? Action, a piece of magic in the kids’ lives and a real piece of grit in the eye of loads of adults and people in authority, had been withdrawn “for editorial reconsideration”. Through the streets of Brixton (truly – several people have recalled this) and no doubt through many other places, rang the cry: “They’ve taken away our comic!” Action, the most important comic for a generation, the one comic in thirty years to win a genuine loyalty from its readers, had gone in for a terminal operation. It wasn’t terminal when it went in, but it certainly was when it came out.

Saturday, October 23 1976 must have seemed a pretty ordinary day when it began. A bit cloudy, not too bad, but like any Saturday it meant, for thousands of kids, heading for the local newsagents to buy their copy of the world’s newest and greatest comic – Action, But when they got there, October 23 was definitely no longer just an ordinary day. There was no Action -and didn’t the newsagent look pleased about it? Action, a piece of magic in the kids’ lives and a real piece of grit in the eye of loads of adults and people in authority, had been withdrawn “for editorial reconsideration”. Through the streets of Brixton (truly – several people have recalled this) and no doubt through many other places, rang the cry: “They’ve taken away our comic!” Action, the most important comic for a generation, the one comic in thirty years to win a genuine loyalty from its readers, had gone in for a terminal operation. It wasn’t terminal when it went in, but it certainly was when it came out.

What, and why, was Action? During the 1950s and 1960s sales of comics boomed, and the two main UK publishers (IPC [then Fleetway] and DC Thomson) produced comic after comic for boys which all followed a formula. This formula owed a great deal to the Eagle, born 1950 as a response to the arrival of crime and horror comics from America. For all its qualities, Eagle represented middle-class, middle-aged Britain fighting to instill a high moral tone in the British young, Eagle and its successors had good clean heroes, straightforward morals, simple adventure, unproblematic baddies, no problem about who would win, or how. Usually the heroes had some special quality or ability that guaranteed their winning through. This was a very successful formula, which worked for twenty years.

But by the late 1960s, things weren’t at all well. Sales were noticeably sliding; many titles were getting perilously close to the then break-even sales point of about 150,000. In 1969, the Eagle itself passed away due to lack of interest. IPC, who committed the euthanasia after taking it over, held their breath against the protest – it was after all very much a symbol as a comic, and a source of nostalgia for so many. Two and a half vicars wrote in, with prayers for its passing. Dan Dare passed into silence, hand-in-hand with the Mekon. Perhaps the climate was changing enough to allow a new kind of comic to be tried.

Both DC Thomson and IPC decided to act. In 1974 DC Thomson brought out Warlord, a new aggressive comic based entirely on the Second World War. Its heroes found life just that bit harder. A greater realism invested the stories, And it sold! IPC had to respond… but there was a problem. Many staff in the IPC boys comic department had been with the company since the 1950s – in some cases since the 1930s – and had been trained firmly in the Eagle tradition. Asked to design a new boys’ comic. they would surely have produced just more of the same. Drastic measures were called for.

The Editorial Director, John Sanders, went outside the company and hired in two freelancers. Their task was to design and get ready a new, different. contemporary boys’ comic. And it was all to be done in secret. The freelancers were Pat Mills and John Wagner: the comic was Battle. Battle was very evidently IPC’s answer to DC Thomson’s Warlord, a tough all-war comic where the heroes were not clean-cut or nice, though in the end they were always on the side of the good.

When news of Battle leaked within IPC, just a short time before the comic’s launch, there was fury in the boys’ department. But there was nothing they could do because Battle proved to be a runaway hit. And with that under his belt, Wagner was given Valiant to revive. (He wasn’t given enough time to succeed). Meanwhile Mills was asked to work on another comic, this time to be really different. For this one, there wasn’t a precedent. It was of course, Action.

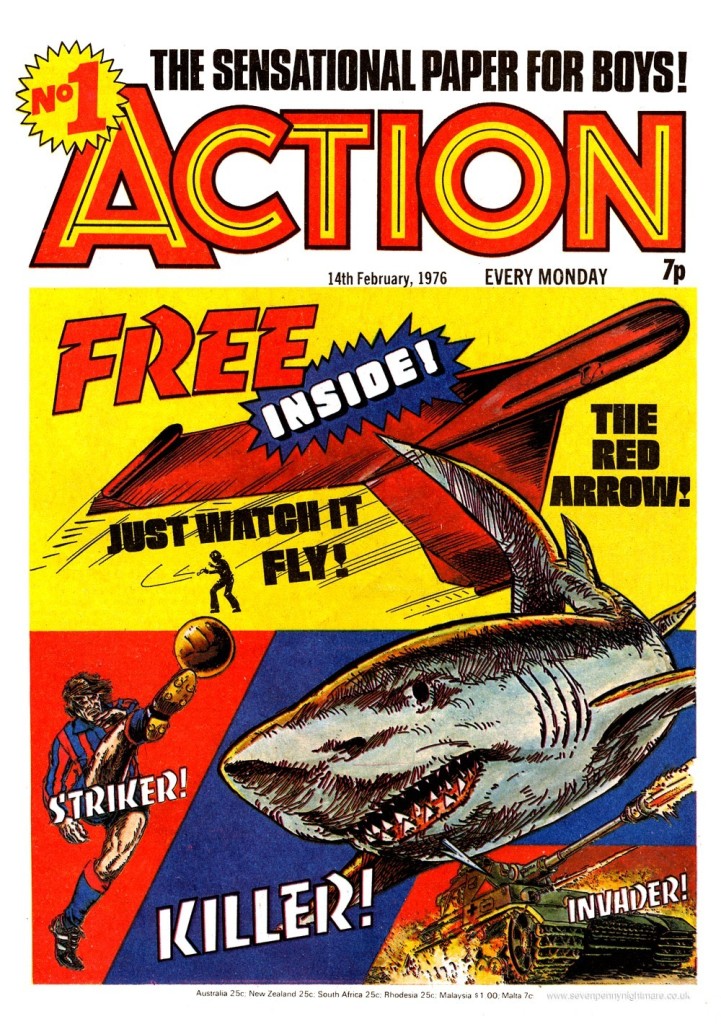

Action first hit the streets (and for this comic, that isn’t just a metaphor) on February 14th 1976.

The initial idea for Action came from John Sanders, who thought that the time was right for a new comic capturing the changed mood of the 1970s. It could appeal to those who probably would not normally buy a comic – or certainly not for long: the streetwise kids. To make this idea into a reality. he called on Mills again. Mills had two words for the qualities he wanted to build into it: ‘difference’ and ‘realism’, and he set about working out a range of story-ideas which would incorporate these qualities.

Given a choice of editors, Mills chose Geoff Kemp, a long-serving IPC man who had edited Lion for some time, but who was desperate for something a bit different. Together they developed that basic formula for Action. The idea was to have a wide range of stories, not tied to a specific theme like Battle (war stories) or Roy of the Rovers (sport) it would instead be a sampler. It would have spy, war, football, sea, boxing, crime and futuristic stories. But each had to be bang up to date.

Suggestions for titles ranged widely: from Boots and Dr. Martens (just for subtlety), to the one they eventually chose, Action ’76. The idea was to stress its up-to-dateness by advancing the number each year of the comic’s life, Sadly, this idea met hostility from the newsagents and the comic became plain Action.

Given three months to create this new comic (a “ridiculously short time” said Mills: “the longest run-in I’d ever known”, said Kemp) they went for a gigantic series of ‘rip-offs’. Jaws was then one of the most popular films for years, so they did a “dead-crib” (Kemp’s words) of it in “Hook Jaw“. Dirty Harry typified the new style of ‘hard man’ films – great, do that too, call it “Dredger“. The Fugitive had become a cult TV programme, so why not do one like it… “The Running Man“? Muhammad Ali had hit headlines all over the world with his brash, raw style – good, crib that too, with “Blackjack“, the story of a tough boxer aiming to be world champion.

However in each case Action did not just rip something off. It changed it, and put its own stamp on the story. Take “Hook Jaw” as an example. In the film the great white shark is an anonymous threat, almost unknown to us except when he rears up out of the sea for a moment to bite someone. That is no way true of Hook Jaw who was the “star of the story” (as Ramon Sola recalled Pat Mills’ advice to him). In fact. Mills called “Hook Jaw”, perhaps a bit rhetorically, an “ecological” story, because of the way Hook Jaw is beset by greedy men trying to kill him.

This difference is typical. In every case, upon entering the comic, ‘rip-offs’ look on a particular Action flavour. The heroes of stories were struggling to survive; life did not come easy to them, and everyone – especially those with any kind of authority – was trying to stop them. They came up from under and had to fight for life, for recognition, for the right to be what they were, This is very important for understanding the popularity of the comic.

The comic opened with eight stories:

Hook Jaw – (Written by Ken Armstrong and others, drawn by Ramon Sola and Felix Carrion.)

Dredger – (Various writers, originally drawn by Horacio Altuna, followed by many others.)

Blackjack – (written by John Wagner, later by Jack Adrian, drawn by Gustavo Trigo and others) the story of Jack Barron, hopeful world boxing champion who discovers he is going blind. But he can’t let down the kids from the ghettos who admire him so much. In the course of working through this dilemma, he meets fight-fixers and other dirty dealers and has to overcome them all. In the end he goes blind after winning the world title fight – and at that point John Wagner, ever a man with a dry sense of humour, handed the story over to Jack Adrian, no doubt with a smile and a “Get out of that, if you can”. The story went downhill as they turned Blackjack into a kung-fu-fighting pop star. Eventually, they finished it with a sudden miracle operation.

Hellman of Hammer Force – (written by Gerry Finley-Day, drawn by Mike Dorey) the first story in a British comic to look at the Second World War from a German perspective. Hellman is a brilliant tank commander who wants to fight a clean war. The Gestapo officer attached to him thinks otherwise and thinks him a near-traitor for doing things like taking prisoners. The conflict between the demands of the war and the pressures of the Gestapo gave this story a good deal of momentum.

Sport’s Not For Losers – (written by Steve MacManus, drawn by Dudley Wynn) a straightforward grimy story about a lad whose father wants him to be an athlete. When the lad breaks his leg, he makes his brother – a fag-smoking oaf of a boy – run in his place. The brother gets into all kinds of trouble but actually starts winning. Originally to have been called Smoking’s a Drag, the story was only half in the emerging Action mode: there wasn’t quite enough tension, pace and desperation in it. What it did have was a fair social comment, on detention centres and the like. We’ll see that this didn’t capture the heart of the comic for its fans.

The Running Man – (written by Steve MacManus, drawn by Horacio Lalia) a really good tense story. Mike Carter, an athlete training in America, is the victim of a face-change operation so that he can take the rap for Mafia man Vito Scarlatti. Mike finds himself on the run from both the police and the Mafia, yet also has to hunt down Scarlatti to clear himself. Brilliantly drawn, it was never very high in the readers’ popularity votes. But it was an important story, for reasons that will be explained later. If there had been more space in this book, this story was next in line for inclusion.

The Coffin Sub – (written by Ron Carpenter, drawn by A. Todaro from the Giolitti Agency) the story of a Submarine Commander who believes he may have been responsible for his previous crew’s deaths. Haunted by this he eventually dies (for which many readers quietly gave thanks!) proving himself after all.

Play Till You Drop – (written by Ron Carpenter, drawn by Barrie Mitchell) a very competent but quite traditional story produced by Carpenter, an old D.C. Thomson writer, in which First Division player Alec Shaw is being blackmailed by a local journalist. The journalist claims to have photographs proving that Shaw’s dad (also a footballer) took bribes. This puts endless pressure on Shaw – to lose key games, to keep his place in the team etc. Mitchell’s artwork for this was excellent, and the story was mildly successful.

It is always interesting to know what didn’t get used. Among the stories considered were one about a photographer whose work involves grim and awful situations: and a fishing story. Mills thought of this latter idea because of the immense popularity of DC Thomson’s “Hook, Line and Sinker”. It also gave scope for a story, based on a very working class sport, able to deal with issues like pollution. Writer Bill Harrington delivered a first episode for consideration, but IPC found it too black and gloomy. The story was dropped.

Action: The Story of a Violent Comic

About the book by Martin Barker

Action: The Story of a Violent Comic – Introduction

Saturday, October 23 1976 must have seemed a pretty ordinary day when it began.

“The Coffin Sub” was the first to go.

The Critics Bite Back – TO BE ADDED

The revenge of the critics and moralists.

Moving in for the Kill – TO BE ADDED

The moralism of Action’s critics finds a voice on the inside.

So, Should Action Have Been Censored? – TO BE ADDED

Action as a hidden pot of virtues, all misunderstood sweetness and light.

Hook Jaw: The Shark Bites Back – TO BE ADDED

Throughout Action’s history, “Hook Jaw” was consistently the most popular story.

The Lost Pages of Hook Jaw – TO BE ADDED

The next extract follows the reprinted material from “Hook Jaw”.

How Lefty Lost His Bottle – TO BE ADDED

“Look Out For Lefty” was not the first football story in Action.

The Lost Pages of Lefty – TO BE ADDED

The next extract followed the reprinted material from “Look Out For Lefty”.

Death Game 1999: Steel Balls to the Finish

A “rip-off’ of Rollerball, but with a difference.

The Lost Pages of Death Game 1999 – TO BE ADDED

The next extract followed the reprinted material from Death Game 1999.

When The Crumblies Flipped It: Kids Rule OK…?

“Kids Rule OK” – the worst villain of the piece.

The Lost Pages of Kids Rule O.K.

Dredger – “rip-off” of Dirty Harry with a touch of The Ipcress File.

After December 4th, the character of Action changed.

People argued that Action lost its way by mid-1976.

• Back to Action: The Story of a Violent Comic – Introduction

This is an excerpt from Action: The History of a Violent Comic by Martin Barker, featured here as part of the Sevenpenny Nightmare project edited by Moose Harris. Text © Martin Barker.

ACTION™ REBELLION PUBLISHING LTD, COPYRIGHT © REBELLION PUBLISHING LTD, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

See this section’s Acknowledgments section for more information