Charley’s War begins just before the Battle of the Somme, when Charley joins a Kitchener Battalion. For those who don’t know the background to the battle of the Somme, here’s a quick summary of the period by Neil Emery. This feature covers the opening day, but technically the battle went on until the same October.

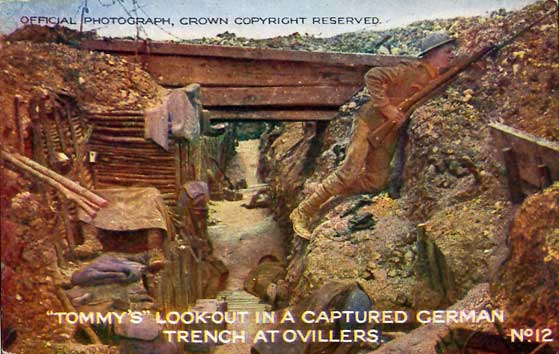

When the British extended their frontline into the Somme area in late 1915, the Divisions that took over this chalky country from the French found the trenches in a bad state of disrepair, many sections of the front line trenches didn’t connect in places. The parados was overgrown with brambles, wire had not been erected and a general air of neglect hung about the line.

The French had regarded the Somme sector as a quiet part of the front, and had been content to allow a small amount of troops to defend it. As a result of this, in the German lines opposite, some of the divisions had been there since 1914 and had had barely a handful of casualties in all that time. Live and let live had been the general feeling amongst the two opposing sides.

This was soon about to change. Since 1915, the British and French High Command had been hatching a plan for a major offensive on the Western Front. By March 1916 the French at Verdun had suffered casualties of up to 90,000 men. In May, the supreme commander of the French forces Joffre conferred with his counterpart Field Marshall Sir Douglas Haig and pressured him to relieve the strain on his hard pressed Divisions at Verdun. Haig agreed and the area of the Somme was chosen as the site to launch an attack. The date was set for 1st July The troops knew it as the Big Push.

A Cast of Thousands

The preparations for such an attack were enormous: behind the British line, roads were constructed, new railways laid, new camps and hospitals built, the trenches were widened and improved, new supply dumps and transport lines were arranged. 2,960,000 rounds of ammunition had been brought up and dumped (Napoleon at Waterloo had 18,000 for all his guns).

Success of the plan depended on the artillery bombardment that would begin the battle. The plan was to shell the German lines for a week non-stop before the British advanced. Specially calculated firing timetables had been drawn up; each gun crew had a mathematically exact table of lifts to adhere to. The week-long bombardment was to be the focus of the entire operation.

The objective of this barrage was to cut the wire in no-man’s land, kill the occupants of the three frontline trenches and disrupt all communication from the rear. It was essential to disrupt the supply of ammunition, food and fresh troops by destroying roads and supply routes.

The plan on paper was to literally let the artillery flatten everything on the German front to enable the infantry to casually walk over and occupy what had previously been trenches.

The men, ecstatic that they were about to freed from the inactivity of trench warfare trusted every word the staff told them, they were finally about to show the world what they were capable of.

Civilian Soldiers

This spirit existed in the British army at this time because these were not regular career soldiers, hardened by the knocks of battle and used to the promises of the staff. The regular army had been all but wiped out in the first years of the war. Lord Kitchener had asked for recruits and the men of the so called New Army had gladly volunteered.

Kitchener had promised them that friends could stay together and fight alongside each other to entice them to take the King’s Shilling. The result was that entire shop floors of factories joined together: they came as cricket teams, football teams, and boy scouts clubs, boys brigades, whole municipal departments and offices. Entire years of universities and public schools went to become the Officers needed to command these men. Under aged school leavers lied about their date of birth to take part in what was believed to be their last chance to be involved in the war.

These men made up the now famous “Pals” battalions. The towns that had produced them raised funds now to equip them. At first they had drilled in civilian suits because their uniforms had not arrived, others with wooden rifles until funds could be raised to buy real ones. They were known by the names of their towns and cities – the Bradford pals, Accrington pals, Salford pals, Liverpool pals.

Men of shorter stature were not to be left out – special Bantam battalions were formed for men between 15 and 53.These were civilian soldiers, each one proud of their background, and the unit they belonged to and each one eager for the chance to show that they were prepared to fight for their country and their Pals.

Each town and city was equally as proud of their own raised battalion – the battalion itself becoming a personification of the area it came from. As the battle drew closer, some of those in command had openly voiced their doubts of the ability of this civilian army to gain the objectives given to them. It was the pals aim to prove these doubters wrong.

The Pals are perhaps the saddest story of the whole Somme debacle and one that left whole streets, schools factories and towns almost bereft of men after the battle. Look at any war memorial in any town square in the country and the majority of the names that you see will have died in a pals battalion and probably on the Somme.

In some ways the country, to this day has still not recovered from the loss. It’s said that every family in the country has at one time been touched by the battle of the Somme.

As the bombardment screamed over head in the run-up to the 1st July, huge models were built behind the British lines, exact scaled layouts of the German trenches were laid down meticulously with tape and the men of the new army practised their roles again and again. Some were to be “mopper uppers” – grenade men whose job it was to follow the first wave and throw bombs down the dugout steps to stop the enemy emerging and shooting the first wave after they had passed. Others were signal men – lumbered with contraptions that looked like steel blinds for signalling aircraft. Each man had a metal flash on the collar of his uniform designed to reflect the sun so the artillery spotters could see the extent of their advance.

All men were to be in fighting kit: belt, bayonet, water-bottle, ammunition pouches, and entrenching tool. On their backs, they carried a groundsheet and haversack containing a mess-tin, tinned rations, extra iron rations, spare socks and laces. Around their necks each had two gas helmets and goggles against tear gas.

Some carried wire-cutters, over half digging tools – either a shovel or pick. These were carried down the back of their packs and made stooping or bending almost impossible.

All carried 150 rounds of .303 small arms ammunition, weighing 10 pounds alone. Extra ammunition was to be slung in cotton bandoliers around the neck. Everyone was told to carry at least two sand-bags, and in many units either two mills bombs or a Stokes Mortar bomb. Often extra burdens such as a stretcher or telephone cables were added.

‘Tickled pink ‘ to go

Not surprisingly, all this preparation had not been missed by the Germans, looking at intelligence reports long before the bombardment had started the German high command had rightly predicted an attack was coming soon. They shifted their divisions accordingly. As the pals wrote last letters home, the shells continually rained down on the German trenches: 24th June, 130,000 shells, 25th June, 350,000. The number rose steadily as the days passed…

The gun crews worked in shifts, stripped to waist as they loaded and reloaded. Huge shells were slammed into red hot breaches- high explosive, shrapnel, 8 inch, 9.2 inch, howitzer shells. The guns stood wheel to wheel as they continually rained screaming steel into the German frontline. The Pals in the over crowded British front line and communication trenches watched the spectacle in awe. Surely nothing could survive the rain of death that guns were producing?

On 25th June, the rate of fire of the British guns increased further still – the shrapnel shells they had been firing were changed to high explosive as it was the belief that the surface nature of shrapnel would be wasted when the topography of the German trenches would have ceased to exist.

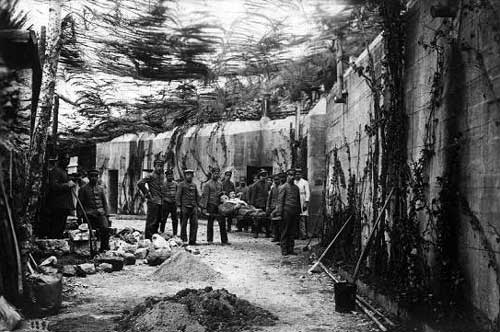

High explosive mixed with gas shells now streamed down in great arcs from the muzzles of the British howitzers. In the deep concrete dugouts the Germans sheltered in the walls shook and the ground heaved with the concussion. Some were buried as the trenches above fell in on themselves but most dugouts survived the onslaught due to the depth and strength of their construction. The Germans had been in a defensive mode from the beginning of the war and over two years, had constructed their deep concrete shelters to be capable of withstanding even a direct hit. They had been mined by engineers and most had two exits in different parts of the trench system. They were 30-40 feet deep and built of reinforced concrete… the Germans, although strained almost to breaking point with the seven day drumfire, and weak from lack of food and water, were very much alive.

In the early hours of 1st July, the barrage intensified to a crescendo never before imagined. Guns of all calibres fired at once, in some places the British sat on their parapets cheering soundlessly at each explosion, their exalted cries lost in the tumult. Eyewitnesses remarked the sound was so intense you could not hear your neighbour, even when he screamed at the top of his voice into your ear.

Another tried to count the detonations by his watch, which proved impossible, so he tried chattering his teeth and found that he could click them about six times a second – but it wasn’t enough to keep up with the rate of fire he watched smashing into the German lines. The sound was a continuous rumble, the report of individual shells now completely lost.

The few Germans who ventured into the storm had observed through periscopes masses of British troops in the front lines. They knew the attack was coming soon.

All along the British line, trench ladders were fixed into place for the eager pals to vacate their trenches… Officers watched the hands on their watches crawl lazily toward 7.30 – the time of zero hour.

To while away the time some of the pals sang a song they had sung on the long march through the French countryside on their arrival: “Break the news to mother, tell her there is no other/ tell her not to wait for me, for I am not coming home” – blissfully unaware how prophetic the lyrics were to be.

”Over the plonk lads”

As dawn broke, the sun shrouded in a light mist, it promised a glorious summer’s day, weather described later by Siegfried Sassoon as ‘heavenly’. The sky was cloudless and from 7.00am the sun shone in complete ignorance of the scene below.

One soldier wrote: “for all my time in France, I never saw a day as beautiful as the first of July.”

At 7.25am, with just five minutes to go before zero the barrage began to lift from the frontline trenches and the guns began to concentrate their fire on the support and transport lines. At 7.28, the ground rocked with the detonation of the Lochnager mine near La Boiselle, immediately followed by the triple tambour opposite Fricourt. The mine at Hawthorn Ridge had been fired at 7.20, its sound lost in the white noise of the final bombardment.

At precisely 7.30am, scores of whistles hanging from lanyards round Officers necks shrilled-the signal for the pals to climb out of their trenches and walk across the couple of hundred yards of no-mans land…

This is a German officers account of what happened next:

“For more than a week we had lived with the deafening drumfire of the battle and we knew that this went on not only in our sector but also in the north almost as far as Arras and southwards as far as Perrone. Dull and apathetic, we were lying in our dugouts, secluded from but prepared to defend ourselves at whatever cost.”

‘A Sunday afternoon picnic’

“On 1st July at 7.30am, the shout of the sentry they are coming tore me out of my apathy. Helmet, belt, rifle and up the steps. On the steps something white and bloody, in the trench a headless body. The sentry had lost his life by a last shell before their fire was directed to the rear, and had paid for his vigilance with his life.

“We rushed to the ramparts, there they come-the khaki yellows, not more than twenty metres in front of the trench. They advanced fully equipped, slowly to march across our bodies and into the open country. But no boys, we are still alive and the moles have come out of their holes…

“Machine gun fire tears holes in their ranks. They discover our presence, throw themselves down into the mass of craters welcomed by hand grenades and machine guns. It is their turn to sell their lives”.

Everywhere along the front, the British walked casually into the smoke: in some places, they slung their rifles to make carrying their burdens easier. In others, they kicked footballs across the shell pocked grassland. In one sector, a man held a hare which ran from the ground aloft on his bayonet to the cheers of his mates. “First blood of the day!” commented one. In places where two companies joined the commanding officers linked arms.

And then the machine guns opened up.

The bullets cut through the dense lines of British troops like a scythe. Many, laden by the equipment they carried, could not find cover quick enough and died instantly. Others found themselves completely alone when they reached the German wire, only to be killed as they stalled, wondering what was happening, what could have gone wrong.

In many sectors when the troops reached the German wire they found it uncut by the bombardment and were shot down while trying to find a gap. Their bodies piled up in heaps at the few places where the shells had done their job.

Whole platoons of pals fell where they stood: whole schools, factory floors, offices and streets were caught on the wire and riddled with bullets. In some places, German soldiers stood uncaring on their parapets, picking off wounded with rifle fire.

The men who were able to take cover in shells holes when the MGs had opened up were now completely pinned down by deadly, accurate fire from the excellently sited German guns. By this time, the German artillery had recovered enough to start a devastating counter barrage and now it was their shells which rained down on no-mans land and the second waves now crowded in the British trenches. The wounded that had fallen in shell holes were pinned down by the lethal fire.

By 10.00am, the British had lost 52,000 men killed or wounded, most of which had been killed in the first hour of the assault. The rest of the 150,000 were pinned down or had gone to ground.

In some places the British had gained their objectives, but they were so isolated and without supplies of ammunition that they held sections of the German line for only a short time before they were either killed or retired. The fanciful signalling devices which were untried in battle had proved to be completely useless. A total breakdown in communication had occurred.

In some places, the British who had made it to the German front lines were even shelled by their own guns when they had failed to lift their barrage onto the German support lines.

The large majority of the non wounded who had found shelter in shell holes now spent the entire day pinned down, unable to move at all. Here they stayed, smoking and swearing in the swelteringly hot July sun. After dark, many would try to crawl back to the British lines and stumble back into the trenches they’d left that morning.

For the wounded, of course, that was impossible. The stretcher bearers, unable to raise their heads above the parapets could only listen in frustration at the screams of the wounded and dying in no-mans land.

When, at last, darkness fell on what seemed like the longest day of the year, most of the injured had died from shock or loss of blood. The slightly less badly hit were still crawling in three days after the attack, but most had died alone and in agony in no-mans land.

A large percentage of the dead were never found and have no marked grave. It’s believed they were buried alive by shells as they lay waiting for help – or were simply blown to atoms by the now frenzied German counter-barrage that raked all along the front.

The Cost of Idiocy

1st July proved to be the end of idealism. Never again would such an almost mystical patriotism be known. A different attitude at the front and at home would prevail from now on. Innocence had truly died along with the pals. Traditional views of those in authority were destroyed for good.

Few battles in history have ever been so meticulously planned and few battles in history have failed as completely and at such high cost. The Somme offensive continued for another four months after 1st July, and in total it would cost 150,000 dead with another 300,000 maimed or wounded.

As Pat Mills rightly points out, these men were not characters from distant history. World War 1 was only 80 years ago. I remember when I was younger and my mum used to take me shopping, she would stand and chat to a guy everyone called Lardy, who had fought at the Ypres. My next-door neighbour’s father had been gassed with the Middlesex Regiment at Loos (a wound that eventually cost him his life when he died of a lung related illness). Another neighbour’s father was a stoker at the battle of Jutland and my own great grandfather, Pop Wythe, was torpedoed when he served in the Merchant Navy. As a child, my grandfather remembered seeing Zeppelins flying high over London, picked out by searchlights.

This is not prehistoric history, it is yesterday, and it’s our heritage. It’s our responsibility not to let it be forgotten.

”Were here because we’re here, we’re here, we’re here because we’re here”

(Tommies marching song- sung to the tune of Auld Lang Syne)

Neil Emery, 2002

Leave a Reply