A version of this article on British girls comics first featured in Memorabilia Magazine in 2002. This version notes the original date of comments made

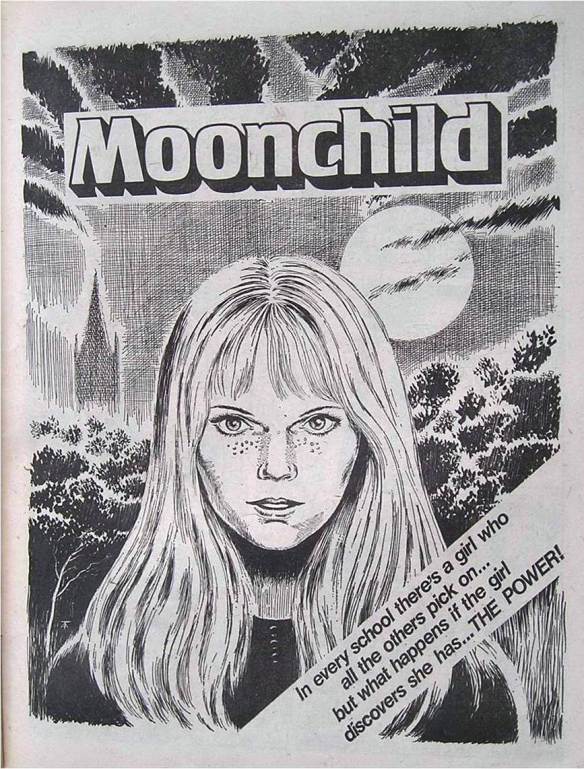

“Bessie Bunter”. “The Four Marys”. “Ella on Easy Street”. “Moonchild”. If you don’t recognise these strips, then the chances are you’ve never picked up a British girls’ comic. Which, according to their creators, is a darn shame, because titles like Bunty, Tammy and Misty featured some of the best comics stories ever written for the traditional weeklies.

While boys’ comics command huge collector interest, girls comics aren’t in as much demand. This may seem a little odd, especially when you discover many of the most memorable stories of the past 30 years, like “The Concrete Surfer” and “School for Snobs” – indeed, hundreds of strips – were written by 2000AD greats like Pat Mills and John Wagner. Girls comics also feature art from prestigious talents such as Enrique Romero (better known for the newspaper strips Axa and Modesty Blaise) Barrie Marshall (“Roy of the Rovers”), Jim Baikie and Casanovas.

Stranger still is the sorry state of the girls’ comics market. Virtually every single title – Bunty, Mandy, Tammy and many others – are long gone. While there are numerous girls magazines still thriving on the news stand in 2015 – and some, like Monster High, have featured comic strip – there are no true “comics” on the news stand, despite the huge number of female comic creators now working in the industry and, it could be argued, an audience waiting to enjoy such fare.

Girls’ comics sold in their hundreds of thousands every week for years – Jackie and SchoolFriend topping one million copies at their peak. What went wrong?

“Girls themselves have changed,” said Agnes Wilson, Deputy Managing Editor at DC Thomson back in 2002, the company that published Bunty, Mandy and many other popular girls titles for decades. Now there’s only Animals and You, aimed at girls of seven to ten.

“The picture story is not as popular,” she said. “There’s more competition for girls time now.” Consequently, as girls now get involved in more sports and clubs, they have less time to read – and are spending money on other things. As comics sales fell, even Bunty, which ran for 43 years, was cancelled in 2001. “Survival is a matter of economics,” admitted Agnes.

Comics creators like Pat Mills, who was heavily involved in the creation of many girls comics well before his better known work on Battle and 2000AD, has different views. Just as he was in 2002 when this article was first written, he’s full of enthusiasm when asked about girls comics, and pins the blame for their demise on the ill-treatment of creators and a lack of understanding of the genre by management.

Pat wrote for DC Thomson, then moved over to the girls’ titles at IPC, creating strips for Tammy, Sandie, Jinty, Pink and Girl. He was also associate editor on Misty, a comic packed with supernatural stories that he considers the female 2000AD.

“Me, John Wagner, Gerry Finley-Day, Malcolm Shaw and several sub-editors who went freelance wrote those comics,” Pat told me in 2002, referring to the 1970s titles IPC published to emulate the huge success of DC Thomson’s Bunty and Judy. They worked without credit – along with many stunning artists unique to girls comics like John Armstrong, who drew the fondly-remembered gymnast story “Bella” for Tammy. “He was a genius with facial expressions,” says Pat. “No artist could match him.”

Together, these creators revolutionised IPC’s girls’ comics in the 1970s – and sales rocketed, with titles like Tammy selling over 200,000 copies per week.

Pat places sales success on creating strips with character, emotion and realism – “hard, gutsy stories that don’t have to have a happy ending… That, combined with a strong camp quality, very clever plotting, ingenious ideas and totally over the top but still realistic concepts.

“There were some notable exceptions, like Pat Davidson, a truly fantastic writer, but many female writers were from the pre-revolution period and simply didn’t get it. The more modern ones did – but they often lacked the surgical ruthlessness that the male writers had, writing hard – okay, cruel – edge needed on stories.

“This may not sound very politically correct, but it’s true. Many of the female writers’ stories were too woolly or too soft. Maybe we just never found the right female writers. As male writers, our ability to precisely press buttons in our readers came because we were trained by DC Thomson, and also because we were observing the female psyche from the outside.

“There’s another important fact which is somewhat controversial. Many young female writers and journalists on the girls’ juveniles were embarrassed to be working on mere comics, especially if they were printed on crude paper. They wanted to be working on trendy, glossy pop magazines as a stepping stone to older magazines like 19 and Honey. So they stressed the feature content of publications like Pink and paid little attention to the comic side, which they saw as a necessary evil, rather than a vital selling aspect of the publication. As male journalists – with little interest in the feature side of girls magazine (after all, what would we know about make-up?!) – we had no such problem.

“So that’s also why male writers worked on girls strip stories – because many female writers found them uncool. Pure snobbery!”

And why are these great comics no longer around? At IPC, many of the writers who’d saved the girls comics were pulled from the titles in the mid-1970s to rescue the boys comics – leading to the creation of comics like Battle and 2000AD. But this brain drain meant pre-revolution editors, who didn’t understand the genre, were put back on the girls’ titles. Sales plummeted and by the mid-1980s, most IPC girls’ comics were no more.

Mills cites his own experience, writing photo strip on Girl as an example of this ignorance. “ I wrote a few series for it, notably “9 to 4”, a Grange Hill-style soap opera which was highly successful, running to two series. The script editor could not understand why it was popular because it featured girls, to use his words ‘standing around, complaining and absolutely nothing happens’. That’s exactly how it would seem if you don’t understand the nature of girls comics where the emphasis is on emotions, not dynamic visuals. Think of Grange Hill or EastEnders. That could be described in the same way.”

“There was another and even more serious reason which is at the heart of all the problems in British comics, then and now,” says Mills. “Creators are not treated with sufficient respect. Even today, there is no recognition that the stories we create are our “intellectual property”.

“Sociologists, media studies and students doing their thesis on the genre will tell you girls comics died because of changes in fashion. That’s an outsider’s opinion and is academic bullshit. The real truth is the f**kwits won.”

Although girls’ comics are a lost genre today, there is plenty of collector interest – but they can be hard to find. “Specialist comics shops don’t handle girls’ comics,” says collector Mike Kidson, who in 2002 was co-editor of online comics mag Borderline. “They’re not of interest to most of their clientele.

“You wouldn’t expect to pay more than a tenner for any other of the hundreds of girls’ annuals published between 1923 and the present,” he adds, “and generally you’d pay much less than that. Supply outstrips demand by a long way.”

However, even in 2002 there were signs that demand was hotting up. “Girls’ annuals, and the comics themselves, are no longer quite as easily found in charity shops or newspaper ads as they were, and eBay competition for them is slowly increasing.”

“When girls comics do come in, they’re quite keenly bid,” revealed Malcolm Phillips at Comic Book Postal Auctions. Most collections of girls comics tend to be of higher grade than boys, and today’s baby boomer will happily pay up to £25 for a comic they recall from their younger days. DC Thomson’s 1960s annuals for titles like Mandy and Judy are popular and titles such as 1970s comics like Spellbound and Misty attract premium prices.

Would a girls’ comic succeed today?

Marcia Allass, Editor in Chief at the influential Sequential Tart web site, was unsure back in 2002. “The present western system of distribution, via the direct market to specialist stores only, and the lack of availability on news stands, is a drawback to success. That said, I still see more girls reading on trains and buses than boys. If things were widely available to them that addressed their tastes and attitudes, they’d buy them.”

Mel Gibson, who wrote a PHD on girls’ comics and runs training and promotional events about comics and graphic novels and whose book, Remembered Reading, about girls comics, was released in 2015, feels girls are missing out through the disappearance of once hugely popular comics like Bunty and Jackie.

In 2002, her research revealed just five per cent of comics readers were women and the massive growth in girls “consumer culture” meant they were not benefiting from the experiences enjoyed by their mothers in the 1960s, seventies and eighties.

Thankfully, those figures appear to have changed, with the rise of popularity in comics among female readers, evidenced by greater numbers of women and girls at major conventions, and a welcome growth in the number of female comic creators.

Although growing interest in Japanese manga is reviving girls’ interest in comics, there’s still a long way to go to secure the success of Bunty, Mandy and Tammy at their height.

“I like the idea of opening them up to the possibilities that comics offer,” said Mel in 2002. “They’re often very different from the other fictions they read. It’s also an issue of visual literacy, of learning another way of reading.

“Comics need to widen their audience to survive. In many ways this is a great time for comics, in that there is so much wonderful work out there to enjoy,. However, in terms of profit, it’s not.”

In 2002, Agnes Wilson revealed that DC Thomson continue to watch the market very carefully and have researched the possibility of creating a new title. “We’re always exploring new angles,” she says. “If we thought there was an opportunity, we’d take it.” Since then, of course, the company has had considerable success with their Jacqueline Wilson title (a writer who cut her teeth working at DC Thomson), but it’s not the comics many still remember.

“Over the years I have said to publishers many times, ‘Why don’t you reprint the Best of Misty … or the Best of Tammy … and offered to point out the hit stories,” said Pat Mills. “After all, the cost of reprint would be negligible. And I’ve argued that if they were successful – even only in a nostalgia market – it could pave the way for a cautious revival. No one has ever shown the remotest interest.

“The reason is frighteningly simple. They don’t understand the genre. It’s a total mystery to them – a secret world which they wouldn’t begin to, or want to understand.

“But for a decade between 1972 and 1982 many of us spent a very happy and creative time writing for that secret world.”

Girls we remember…

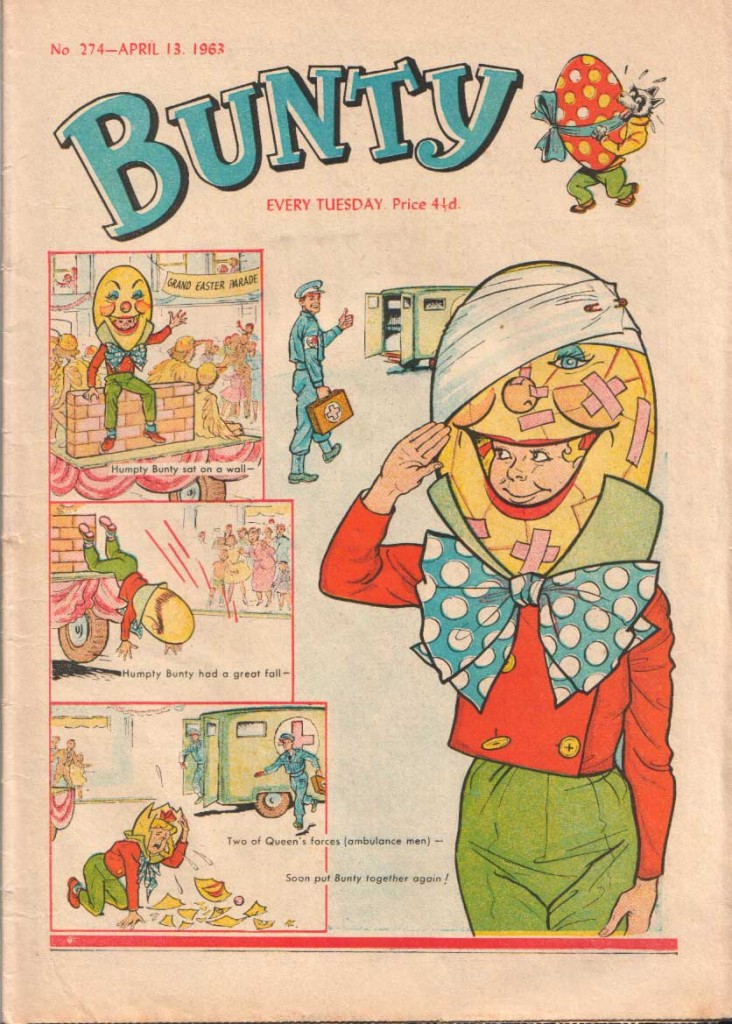

Bunty: 1958 – 2001

“Bunty was at the head of the pack right from its debut until the late 1990s, by which time it was the only girls’ comic left,” says collector Mike Kidson. “It achieved that status of being the identifying label by which the whole field is referred to.” The title included boarding school tale ‘The Four Marys’ which ran for six decades!

• Bring Back Bunty Facebook Group

This group is not calling for a return of Bunty as it was, more what it could be today… a weekly supply of original stories in a quality British girls’ comic – and the alliteration works well! There is nothing in the local newsagent that we could call a girls comic, whereas in the 20 years ago there was an enormous choice – and girls read the boys ones too!

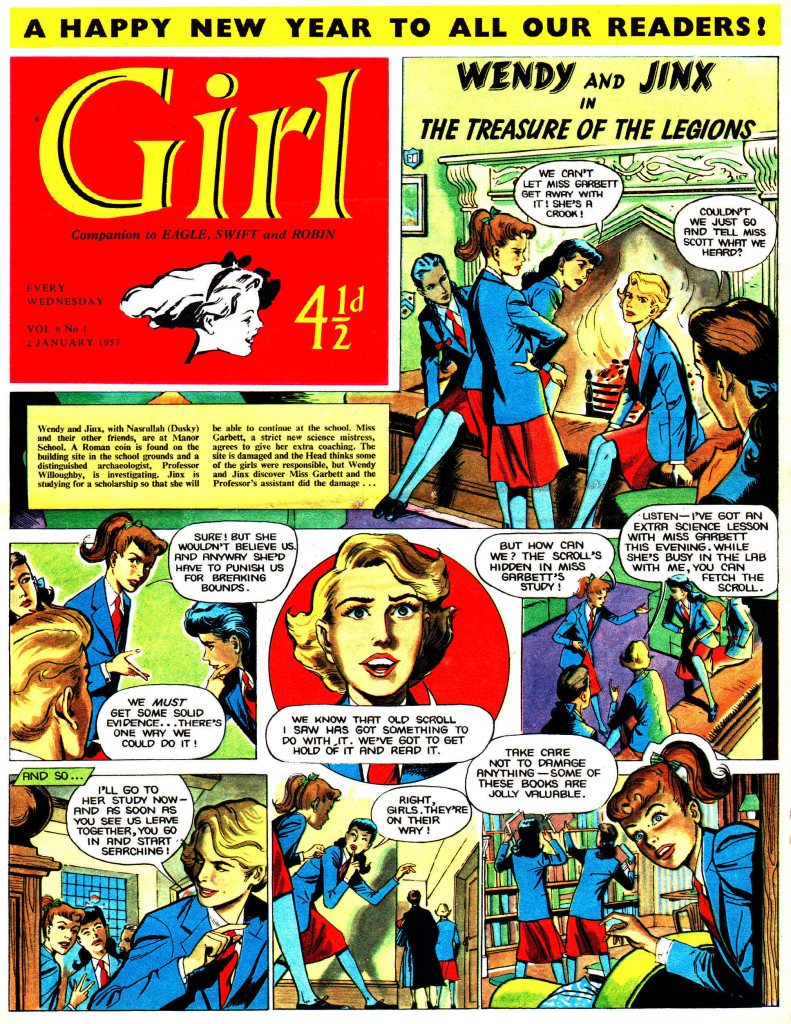

Girl: 1951 – 1964

Not to be confused with the later IPC title, Girl was the stable mate of Eagle. While a copy of Eagle Issue One can fetch anything between £50 – £10 in reasonable condition, its female counterpart rarely fetches more than £20. “That’s despite the fact they’re the same in terms of [editorial] quality,” says Malcolm Phillips.

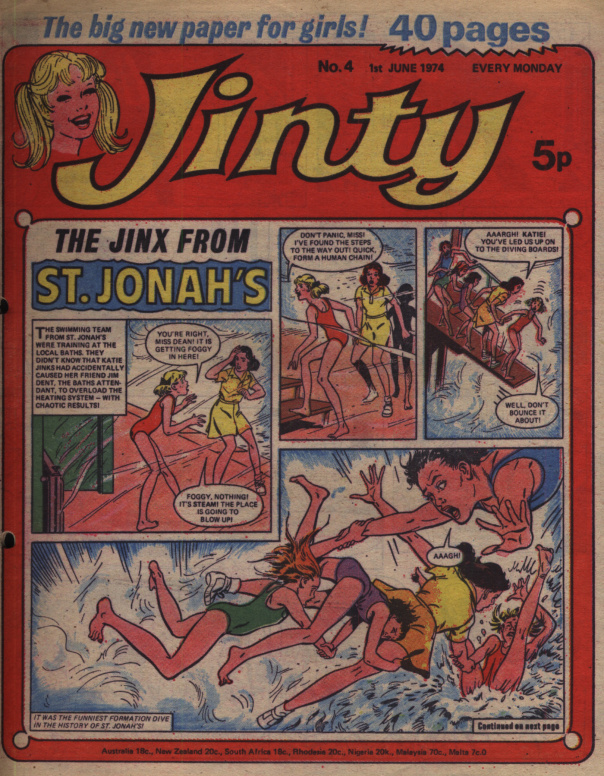

Jinty: 1974 –1981

Jinty featured characters far from the stereotypes of boarding schools, secret agents and pony riding – although they contained some of the aspects of them. Stories included “Children of Edenford” – a chilling Stepford Wives-type tale – and Pat Mills’ skateboarding tale, “The Concrete Surfer”.

“Women buy a lot as back issues,” says Will Morgan from the 30th Century Comics store (www.thirtiethcentury.free-online.co.uk), one of the few comic stores to promote its stock of girls titles. “It had a more street-level, adventurous slant, and is fondly remembered by thirtysomething women.”

Inspired by the UK Girls Comics Index and by the Tammy Project, the purpose of this blog is to be a index for the Jinty title.

• The Complete List of Jinty Comics

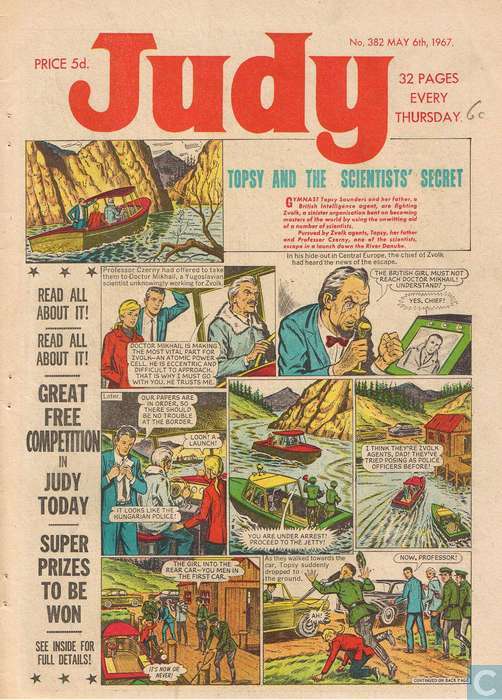

Judy: 1960 – 1991

Judy featured everything that was good about girls comics back in the 1960s – the sort of comics success IPC sought to emulate with its “revolution” titles in the 1970s. Its formula of romance, orphans, school and girl-next-door stories survived even the 1980s, when consumer-led magazines for girls were on the rise.

Mandy: 1967 – 1991

Mandy was published weekly by DC Thomson from January 1967 until May 1991, merging with Judy in 1991, becoming the title M&J, merging with Bunty in 1997.

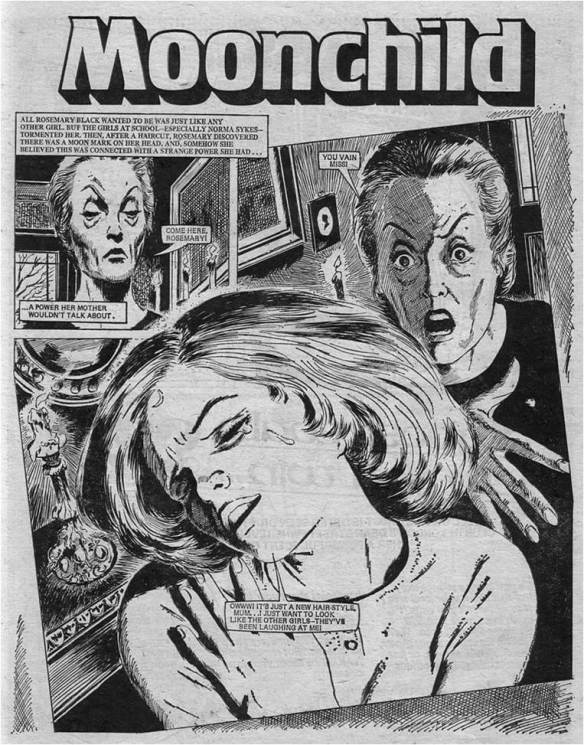

Misty: 1978 – 1980

Introduced by IPC to mimic the success of DC Thomson’s Spellbound, this is, says Mike Kidson, “the only girls’ comic to have attracted the attention of American comics fandom in the UK.” Misty annuals are much in demand on eBay – though beware, because the content of most in no way matches the quality of the original comic.

“The idea was to apply the rules of 2000AD to girls comics, including larger visuals,” reveals Pat Mills. “Specifically to use role models such as Carrie, Audrey Rose, Flowers in the Attic. If this had been done properly, it would have been a runaway best seller. I still regret not devising Misty and I feel if I had, it would still be around today. As it is, I wrote ‘Moonchild’ (a serial based closely on Carrie) for the launch and this went down well.

Misty had a firm following, “but it had too many stupid adventure stories in with colourful visuals,” says Pat, “Female readers generally care more about story than art. In male comics, it’s often the other way ‘round. I think I’d better resist commenting further!”

• The semi-official Misty Comic web site is here: www.mistycomic.co.uk | Facebook | Twitter

• Pat Mills on “The Female 2000AD”

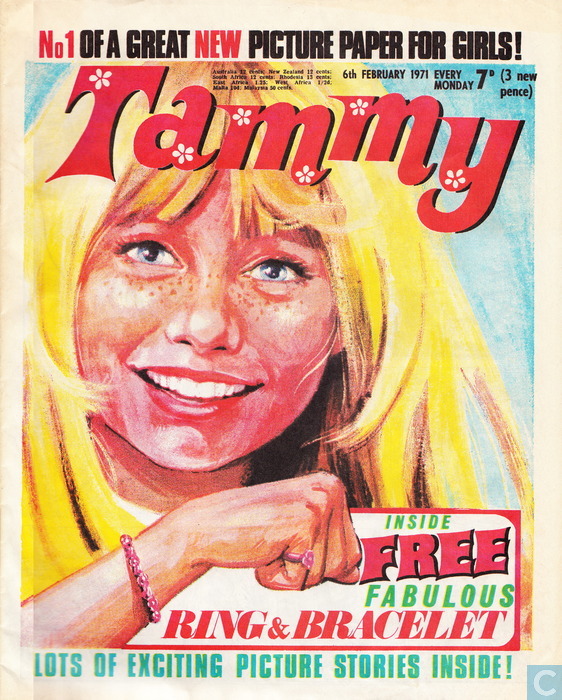

Tammy: 1971 – 1984

Always a title keen on a good weepy, Tammy rivalled DC Thomson’s Bunty in sales terms. Tammy incorporated six other titles during its lifetime, including June and Jinty. It introduced us to “Girls of Liberty Lodge”, “Slaves of War Orphan Farm” and good old “Bessie Bunter”, created decades earlier by Frank Richards.

This great site includes an index of Tammy stories.

General Links

A general site about British girls comics

A terrific general site on classic girls comics. A fan site dedicated to British girl comics of the past, looking mostly at the long running publications of Bunty, Mandy and Judy, but also some of the other D.C. Thomson like Nikki, Emma, Spellbound and IPC comics like Misty.

• Female writers in a girls’ genre by Jenni Scott

For a genre based around a female readership, you could be forgiven for thinking there were hardly any women involved in producing British girls comics… Jenni’s extensive research reveals this isn’t the case

• Jenny McDade: Creating Tammy

Author Jenny McDade writes about her work on the well-known girls comic

• Why girls’ comics were wonderful, by Jac Rayner – BBC archived article

Jac Rayner looks back on the plucky young heroines who perished in the Great Comics Bloodbath, from “Diving Belle” to “Lisa the Lonely Ballerina”

• Dr Mel Gibson has done a lot of research into British girls comics: www.dr-mel-comics.co.uk | You can read more about her 2015 book, Remembered Reading, here on downthetubes

Derek Pierson writes: “Bang on the money again, John! I’ll have to go get another box of tissues … I worked with John Wagner and Malcolm Shaw on Jinty, edited by Mavis Miller. What a vibrant little stable that was at Fleetway – you only had to leave the office door open and their ideas were halfway down Farringdon Road! And Malcolm Shaw was a lovely lad who was taken from us far too early. And who would have thought the World-famous Judge Dredd would have emanated from such, some would say, humble beginnings. Your’s and Steve Holland’s research is phenomenal, thank you.”

Great stuff, John, as ever. Having said that I would really like to get a wider view on some aspects of it other than Pat Mills’s well-known take on the role of women writers. Of course he was there and has a strong basis for his opinions, and I think his memories on the reactions of female staffers to working on a girls comic are important.

On the success of stories themselves, though, his take on it is an editorial one and not a reader’s own one, of course, and I think he is liable to underestimate the popular reader reaction towards stories of types he is not interested in. There were women writers, like Alison Christie, who wrote extremely popular and well-received stories that were reprinted and translated worldwide (not that anyone told her about this at the time). Her stories were tear-jerkers, not in Pat’s line – they were extreme in a different way, not cruel and sadistic but still powerful, and well-remembered by the readers, as it turns out. I wrote more about this on my blog, which you’ve linked to above – “Female Writers in a Girl’s Genre“.

Having said that, in the case of Jinty at any rate we just don’t really know enough about who wrote what. Right now I couldn’t really tell you who wrote some of the most striking, weird, and avant garde stories on that title. Who was behind the Stepford schoolchildren of “Children of Edenford”, or the ultimately extreme story “Worlds Apart”, which haunted me for years afterwards? We need to know more from the people who were there.

Thanks for the comment, Jenni – as you know, outside of DC Thomson, there are scant records of who wrote what on British girls comics and your article is a great update on previous perceptions of those involved. I hope your researches shed further light on the people behind these classic comics.