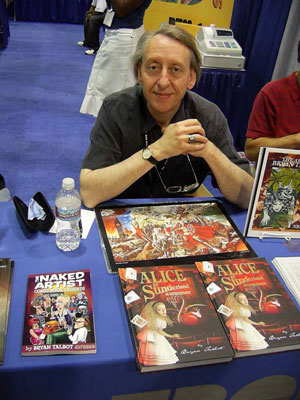

Bryan Talbot, author of Alice in Sunderland and the Naked Artist at the NBM booth, San Diego ComicCon 2007. Photo courtesy of Chris Butcher (www.beguiling.com)

First published 30th March 2007

In a special interview with one of Britain’s top creators, Bryan Talbot outlines his new project, Alice in Sunderland to his son, Robyn…

Bryan Talbot is one artist whose career I’ve followed with much interest over the years. From the early days of Brainstorm Comix and the groundbreaking The Adventures of Luther Arkwright to his more recent The Tale of One Bad Rat and Heart of Empire, his work has held a special fascination for me.

Well, it would do really, because he happens to be my dad. Many of my childhood memories involve him being hunched over a drawing board summoning up the fantastic worlds of Arkwright and Nemesis (the excitement of the fact he that he was drawing for 2000AD far outweighed any consideration that this was putting food on the table).

Like Arkwright and Bad Rat before it, Alice in Sunderland, his latest project, is another labour of love from this master storyteller, taking around five years to complete. I haven’t read it yet, so I’ll let him tell you about it

ROBYN TALBOT : Okay, I guess there may be at least a few souls out there in comic-land who know nothing about this project. How would you pitch Alice in Sunderland to them?

BRYAN TALBOT: Um. The toughies first, huh? No, I’m serious – I’m still having a hard job describing it. I can’t really compare the whole of it to another graphic novel and say “It’s a little like that”. I’ve been using the term “dream documentary”, but that’s vague and more than a little vacuous. It’s actually a book about stories and storytelling, presented in the form of an imaginary theatrical performance on the stage of the Sunderland Empire. Stories, lots of stories, the central two being those of the history of Sunderland and the lives of Lewis Carroll and his supposed muse Alice Liddell, both of whom had connections with the city.

RT: It must have required a tremendous amount of research?

BT: That’s right. I was reading books about Carroll and Sunderland history in my spare time for about three years before I started writing it and continued for the three or four years it took to write and draw. The local studies library here was invaluable and the staff occasionally would dig up files long-hidden from public view for me to photocopy. As well as all the Carroll-related sites around Sunderland, I also visited Croft-on-Tees where he grew up and Oxford University.

BT: That’s right. I was reading books about Carroll and Sunderland history in my spare time for about three years before I started writing it and continued for the three or four years it took to write and draw. The local studies library here was invaluable and the staff occasionally would dig up files long-hidden from public view for me to photocopy. As well as all the Carroll-related sites around Sunderland, I also visited Croft-on-Tees where he grew up and Oxford University.

RT: It’s also partly autobiographical, isn’t it? Does that mean that I’m in it?

BT: Yes! You and Lisa are members of the theatre audience at one point, along with your brother Alwyn. It’s only slightly autobiographical in that I bring my grandmother into the book, as she seemed very relevant to some of the themes. The book is dedicated to your daughter Tabitha and she does appear in there too, bringing things full circle. I suppose that as you’ve recently had another daughter, Madeline, I’ll have to do a book I can dedicate to her so that she won’t be jealous!

RT: Well, no great rush on that one. She’s happy to make do with just a bottle of milk at the moment. How far, if at all, did you find that you had to rethink your approach to storytelling with Alice?

BT: As I said, the book contains lots of stories and I decided quite early on that they should be done in different comic styles, according to their needs. It wasn’t particularly hard to choose the styles as I found that each story screamed out for its own approach. The ghost story of The Cauld Lad of Hylton, for example, demanded to be told as an EC horror comic. The patriotic tale of Jack Crawford, the hero of the Battle of Camperdown, the sailor who “nailed his colours to the mast”, obviously suited a Boys’ Own Adventure style, complete with text under each frame with distressed type on yellowing newsprint paper stock. One section where I’m talking about being in Morocco is drawn like Herge’s Tintin – the setting reminded me of The Crab With The Golden Claws.

RT: I know that in the five year period while you were working on the book, you had to turn down a not inconsiderable amount of high-profile paid work. While you were working on this ambitious, scholarly, serious, funny, and to some extent, self-indulgent, tour de force, without commission or, indeed, a publisher did you at any point in consider that what you were attempting was utter, utter madness?

BT: Of course I did. I thought I must be crackers. Half-way through the book, I have a genuine crisis of confidence and scream at the reader: “Will I ever get paid for this?” It was heartfelt!

I’ve been worried about the book all along – something that’s never happened to me before, working on my others, which I was convinced were the best things since sliced bread. Alan Moore’s opinion was that if I was really nervous about it, this meant I was doing something good. It seems that I needn’t have worried. The first few bits of feedback and reviews that have started coming in have been a hundred percent positive. So far.

Panels from Alice in Sunde

RT: Was it particularly challenging to deal with the thorny issue of Carroll reputedly, how can I put this, ‘liking’ kids a bit too much?

BT: Yes, he loved kids but not in that way. There’s absolutely no evidence anywhere that he was a paedophile. He grew up in a family where he was the eldest of eleven children and spent most of his time entertaining them with games and stories and he missed them greatly when he moved to Oxford. He had what he described as a ‘golden childhood” at Croft and spending time with children was a way of trying to recapture the feeling of innocence and lack of cynicism. Even so, he did state somewhere that although he enjoyed their company he thought ‘grown-up company much more entertaining”.

I do deal with the issue in the book but only briefly, to dismiss it.

The image of Carroll as a shy Oxford don who was only happy in the company of children is a myth – one fabricated in his first biography, written immediately after his death by his Sunderland godson, his nephew Stuart Collingwood, in Guildford and overlooked by Carroll’s aging spinster sisters. As he was by then a world-famous children’s author they censored his adult life, making out that he had no interest in girls once they reached puberty. This was utter bollocks. He had many women friends, some of them visiting his suites to the point of Oxford scandal. Women loved his company – he was charismatic and intelligent. He remained friends with the girls he knew as they grew up, many of them eventually writing books about their relationship with him and often claiming to be the inspiration for Alice.

Not one of them claimed he did anything untoward. Many of what he called his “child-friends” were actually over twenty-one. Ironically, the censoring of his sex life didn’t foresee Freudian interpretations of the biography which, for over sixty years, remained the primary source on Carroll. All other books on him had to use this as a base and then postulate. It was the late 1960s before his diaries were acquired by the British Library and, even then, many scholars didn’t consult them. This actively bred myths: someone would postulate a notion in one book that would be taken as fact by the next.

Of course, the fact that he famously took nude photographs of children is always trotted out to “prove” that he was a closet paedophile but it actually does no such thing. From our current perspective, against the background of the long-running child abuse moral panic, it’s hard for us to accept that Charles L Dodgson was as innocent as he seemed and that we are imposing 21st century mores onto a man with Victorian sensibilities who lived in a very different world.

In the mid-nineteenth century, probably due to the high rate of infant mortality, the cult of the child was huge. Naked children, as a symbol of innocence, were fashionable mainstream fare. They appeared in paintings, sculptures, book illustrations and even on post cards and greetings cards. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were patrons of child nude photographic studies.

Carroll taking such photographs may appear suspect through our eyes but it has to be seen in context. You have to remember that he was one of the foremost Victorian photographers and a pioneer of photography as an art form. He took hundreds of pictures – at a time when each one was extremely difficult to develop and print. It was a painstaking business and took a long time. And, out of these hundreds of photos, how many were of naked children? Six. He wasn’t ashamed of these in any way. They were so unremarkable to his contemporaries that he farmed them out to be professionally coloured – basically over-painted at a photography store so they resembled paintings. I’ve seen them. They’re extremely twee and Victorian “arty”.

When mores changed in the latter half of the nineteenth century and what we think of as Victorian prudery began to kick in, he simply stopped taking them.

This all seems to me to be a case of evil being in the mind of the beholder and a little knowledge being a dangerous thing.

RT: Alice has the clear potential to reach out to a whole new audience of ‘non-comix’ people, a case in point being the interest shown by the Lewis Carroll Society of North America, who have invited you to address them in New York this April. What do you think such people will make of the myriad visual references to Jack Davis, EC, Kirby, DC Thomson and the likes?

BT: I’ve absolutely no idea. Are you trying to make me nervous again? I hope that they’ll simply like the drawing and enjoy the narrative in those sections. I think that I made the book rich enough to be enjoyable to non-comic readers without them having to get all the comic references. They’ll just see the pastiches as different styles of storytelling.

The incredible thing about addressing the LCSNA at their conference is that it’s at the same place, Columbia University, where Alice Liddell Hargreaves received her honorary doctorate seventy five years ago – the event around which the film Dreamchild is based and a scene I illustrate in the book. I’m also going to be giving a talk at the U.K. Lewis Carroll Society meeting in May in London (I’m a member).

RT: I can personally attest that, prior to living in Sunderland, you were based in Preston, Lancashire, for at least twenty-five years. In that time, did you ever consider a similar project inspired by those environs? Bear in mind when answering that I still have to live here.

BT: This book came about because I’d harboured a desire to do a book based around Alice for twenty years. When Mary and I left Preston about nine years ago and moved here, I discovered that Sunderland had many links with Alice and that was what started it off. I did actually read up on Preston history at one time but nothing jumped out as being potentially the subject of a GN, though I did partially name Luther Arkwright after Richard Arkwright. He was one of the fathers of the Industrial Revolution who, as you know, lived not half a mile from where we used to live in Preston centre, in Arkwright House, where he invented the spinning frame.

“Alice in Sunderland is parochial in its focus – but not in content. I believe anyone interested in the way history is formed and, in itself, forms culture, character and a sense of place will be entranced by it.” —

— John Tufail, Carrollian scholar

“The narrative and artwork are magic and the structure is magisterial”

— Leo Baxendale, “The Father of British comics”

RT: Finally, I’ve got to know – was it brillig and did the slithy toves really gyre and gimble in the wabe? Put me out of my misery here.

BT: As far as I can ascertain, it was and they did. Not only that but all mimsy were the borogoves and the mome raths outrabe.

RT: At last I know. Thanks for taking the time out to do this interview. Can’t wait to finally read Alice in Sunderland after seeing it in progress all these years.

BT: Cheers, Robyn. My pleasure.

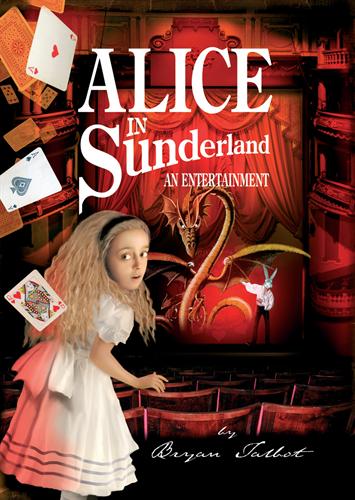

• Published by Jonathan Cape in the UK and Dark Horse in the US, Alice in Sunderland is available now from all good bookshops. You can also buy it from Amazon.co.uk

Sunderland! Thirteen hundred years ago it was the greatest centre of learning in the whole of Christendom and the very cradle of English consciousness. In the time of Lewis Carroll it was the greatest shipbuilding port in the world. To this city that gave the world the electric light bulb, the stars and stripes, the millennium, the Liberty Ships and the greatest British dragon legend came Carroll in the years preceding his most famous book, Alice in Wonderland, and here are buried the roots of his surreal masterpiece. Enter the famous Edwardian palace of varieties, The Sunderland Empire, for a unique experience: an entertaining and epic meditation on myth, history and storytelling and decide for yourself — does Sunderland really exist?

From Bryan Talbot, the acclaimed creator of The Adventures of Luther Arkwright and The Tale of One Bad Rat, comes Alice in Sunderland, a graphic novel unlike any other. Funny and poignant, thought-provoking and entertaining, traditional and experimental, whimsical and polemical, Alice in Sunderland is a heady cocktail of fact and fiction, a sumptuous and multi-layered journey that will leave you wondering about the magic that’s waiting to be unlocked in the place where you live.

[amazon_link asins=’0224080768,0224084704,1616553871,0224102346,0224096087,0224084887,1910702242,0224098063,0224096249′ template=’ProductCarousel’ store=’downthetubes’ marketplace=’UK’ link_id=’8f468fc2-7ed5-11e8-a1c7-f1623f70812f’]