Review by Tim Robins

When David Bowie died, the young-ish, more musically accomplished regulars at my pub turned an open mic night into a wake. It was a moving experience, seeing just how very much the late rock star meant to a generation of straights and queers and otherwise questioning folk. The new documentary, Moonage Daydream, is mostly silent about Bowie’s relationship to his audience, although a familiar clip from a 1973 concert Bournemouth’s Winter Gardens shows a young woman sobbing that he is “smashin’”, while her friends excitedly and repeatedly claim that they touched his hand. A different clip includes a young man in full Aladdin Sane make-up because “It looks good so why not wear it”? A young woman accompanying him in the queue agrees that the make-up is camp but it is also “sexy”.

It is clear that, back in the 1970s, a great number of baby boomers looked around post-war Britain and, seeing little to offer in traditional gender and class based career expectations, decided to forge new identities out of the bright distractions that were being woven from the postwar music mills. After several false starts, Bowie himself tuned into glittery diversions of glam rock, a genre that seemed made for the then new media technology of colour television. The performer set about transforming the possibilities for what being a man could be. For me, Bowie, not Hawkwind, was the musical accompaniment to the fiction of Michael Moorcock whose anarchic science romances were often built around polymorphously perverse heroes from across the multiverse.

Moonage Daydream, writer-director Brett Morgan’s docu-rocku-mentary makes full use of the Bowie family archives to create a cut up biography pasted together from multiple sources including Bowie’s TV interviews, film and stage roles and concerts to present a case study of a mind adrift in an ever changing, chaotic world.

The film is something of an indulgence. Morgan, building on his storytelling techniques in the 2015 film, Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, doggedly focuses on the interior world of Bowie, including his continual self-questioning and surprising doubts that are veiled behind his accomplished performances.

We are shown an adventure in existentialism, in which Bowie heroically strives for authenticity and determinedly pursues his artistic projects in what existentialists call “good faith” – accepting responsibility for one’s own actions and confronting the givens and limitations of life in order to fully realise one’s self. Existentialism asserts that we are condemned to freedom. “And I want to be free”, Bowie repeatedly asserts in “Hallo Spaceboy”.

Fortunately, Bowie in person is a lot less pretentious than his philosophising, and the opening moments of Moonage Daydream that cite Nietzsche would suggest. In a moment shown in the trailer Bowie, in drop earrings and a clownishly colourful suit, is asked, by TV chat host Russell Harty, “Are those men’s shoes, or women’s shoes or bisexual shoes?” Bowie replies, “They are shoe-shoes, silly!”. A lot of the media back then boorishly took the point-of-view of the general audience, itself an invention of the media’s own making. The result makes media professionals look more alien than Bowie himself. Gender politics became central to what Bowie was about . He wore high-heels when he met Prime Minister Tony Blair, not that Blair seemed to notice.

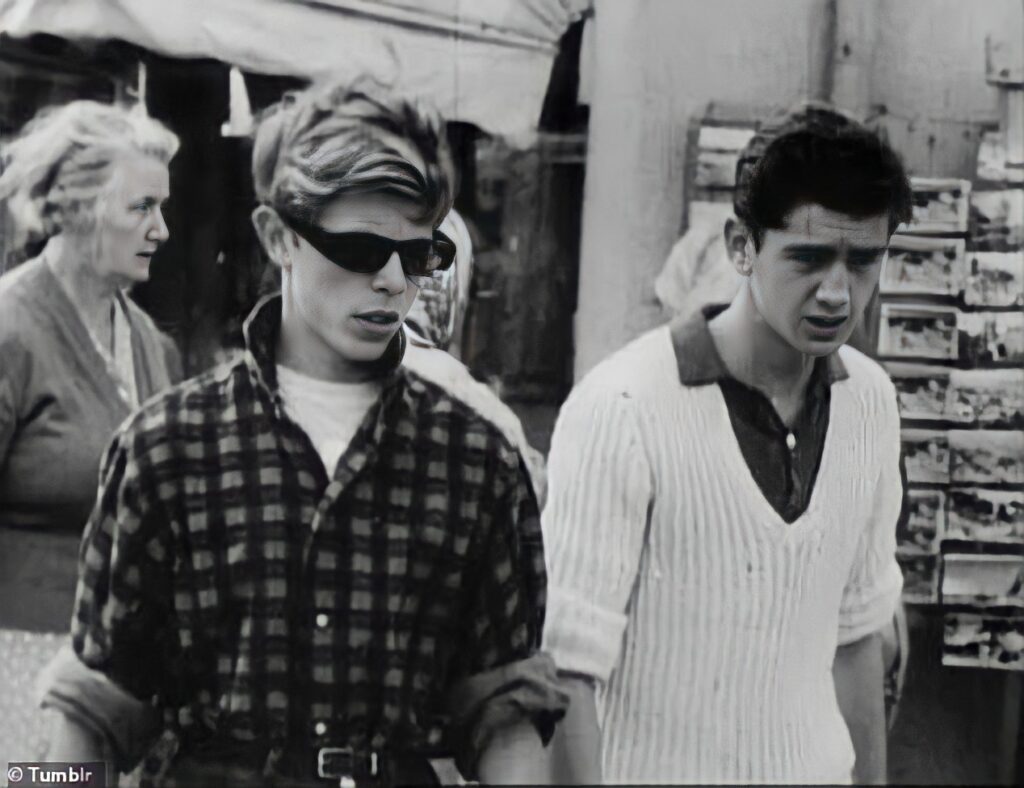

The question of Bowie’s gender never changed from his first appearance on TV at the age of 17 representing his newly-founded ‘Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Long-Haired Men’ on a 1964 edition of Tonight, hosted by Cliff Michelmore. “You’ve got really long hair haven’t you?” remarks Michelmore, nailing the problem on the head. “You see a lot of people can’t tell the difference between a man and a woman can they, if you’ve got your hair that long?” This encounter, not included in the film, seems echoed in the lyrics of “Hallo Spaceboy”: “Do you like girls or boys? It’s confusing these days.”

Moonage Daydream doesn’t explore Bowie’s personas in any detail, which is for the best. It’s old territory. Instead, we are allowed to recognise Bowie’s playful use of characters including a wildly gyrating and pantalooned Querelle of Brest and a rather iffy, pale skinned explorer, a spooky Man from del Monte if you will, walking along ‘exotic’ Eastern streets in search of the finest cultural encounters to pluck from and pocket. I was surprised to find no reference to Bowie’s alleged, scandalous, embrace of fascism during his Berlin period as the “Thin White Duke” – itself a reference to cocaine to which Bowie had become addicted. However, I have decided to divide Bowie’s career into pre and post expensive dental work.

It is helpful if you know something of Bowie’s biography before watching the film, just to relate various moments to his life and times. If you know some of the darkness in Bowie’s life, the film’s flashier, psychedelic moments are tinged with sorrow. Expanding, bright paint effects explode across the screen accompanying Bowie’s time in Berlin when his cocaine habit was exploding his neurons on a daily basis. The film doesn’t overtly address this, either, but when you see Bowie drinking milk and talking gibberish (wisely drowned out in the sound track) you know the drug has him in its grip.

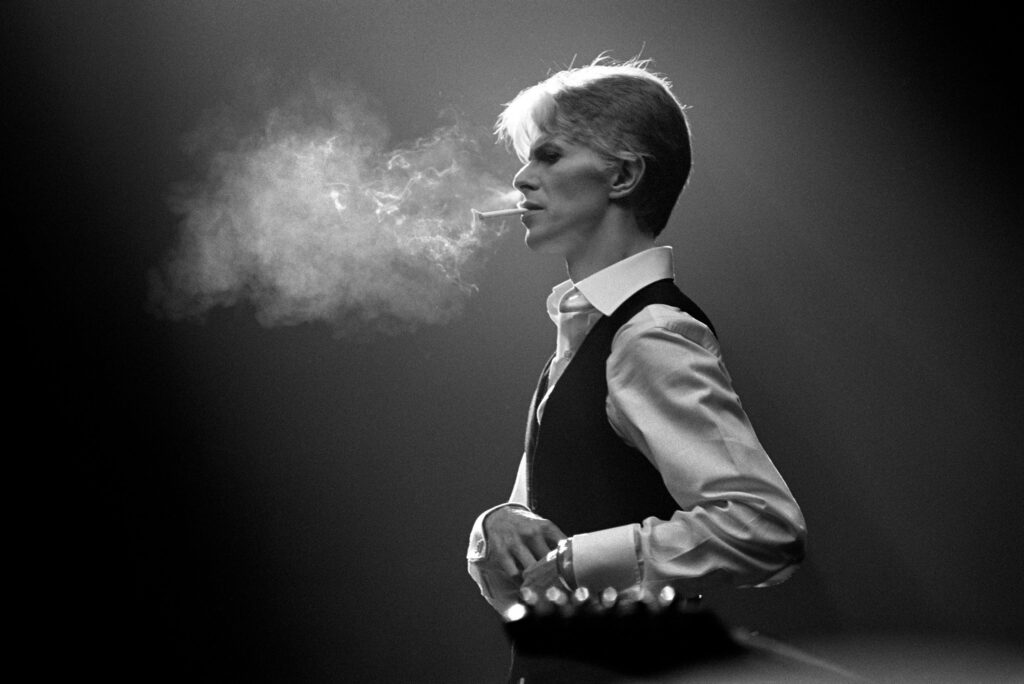

The explosions of light comes again later in the film as it moves towards the end of Bowie’s life. This time, the light seems to represent cancerous cells that were bursting in Bowie’s body. Bowie would die of liver cancer, probably triggered by his cocaine use and heavy smoking, the latter part of a deadly affectation that inflicted people in the 1960s and 70s. Bright colours indicate moments of excitement and danger.

There are many ways to put Bowie in the context of his time but Moonage Daydream uses none of them. In fact, the film barely indicates the passage time. Bowie’s music, for example, is not presented chronologically, but is used to establish a mood or a theme, including Bowie’s sense of self. So the film opens with a novel choice of tracks including the far from expected “Hallo Spaceboy” and “Wild Eyed Boy from Freecloud”.

Each step forward is also a moment of reflection on the past. The documentary is a tentative adventure and time passes as a digression rather than an arrow. I must confess that I began to wonder where this was going and how it would end. But lives, of course, only end one way – with death. Morgan prepares us for life without Bowie by repeatedly cutting to black.

If all of this sounds trifling, or makes Bowie look like some kind of half baked soufflé of a man, then I have done the film and Bowie himself a disservice. Bowie remained grounded, rooted in his difficult working-class childhood and the tragedy of his half-brother Terry Burns who developed schizophrenia on his return from the RAF. It was an adventure too far. Sometimes, Bowie seems to have been living out Burns’ creative vision. The film shows extracts from the video for “Jump They Say”, a song reflecting on Burn’s schizophrenia and eventual suicide by dying on the tracks at a railway station.

Bowie’s warmth and self depreciation prevented him becoming music’s answer to such internet false prophets as Jordan Peterson and Russell Brand as did his willingness to embrace chaos and change. Bowie embraced participation. It would be great if a sing-along edit of the film could be made. I’m not going to put a ray gun to your head to make you go see Moonage Daydream. You are free to choose.

Tim Robins

• Moonage Daydream is in selected cinemas now

A freelance journalist and Doctor Who fanzine editor since 1978, Tim Robins has written on comics, films, books and TV programmes for a wide range of publications including Starburst, Interzone, Primetime and TV Guide.

His brief flirtation with comics includes ghost inking a 2000AD strip and co-writing a Doctor Who strip with Mike Collins. Since 1990 he worked at the University of Glamorgan where he was a Senior Lecturer in Cultural and Media Studies and the social sciences. Academically, he has published on the animation industry in Wales and approaches to social memory. He claims to be a card carrying member of the Politically Correct, a secret cadre bent on ruling the entire world and all human thought.

Categories: downthetubes News, Features, Film, Other Worlds, Reviews

In Review: MONOLiTH: AN ACE ODYSSEY by David Leach

In Review: MONOLiTH: AN ACE ODYSSEY by David Leach  In Review: The Marvels

In Review: The Marvels  In Review: Meg 2: The Trench

In Review: Meg 2: The Trench