By Peter Duncan

In Britain, more so than in other parts of Europe, the general view taken of comics is that they are little more than trash literature, aimed solely at children and not to be taken seriously as an art form. Comic fans, often dressed as spacemen or barbarians, have loudly proclaimed that the objects of their obsession are misunderstood and underestimated and deserving of much more serious attention.

In recent times, however, their claims have gathered some support and the academic examination of comics has become a respectable field of study*, with university courses on comics spreading into the world of literary analysis and beyond.

In this article, we look at academic Journals, edited, at least in part, in the UK and come to see that some very interesting things are happening in comics academia.

European Comic Art, edited by Laurence Grove from The University of Glasgow, Ann Miller, from the University of Leicester and Anne Magnussen, from Southern Denmark is “devoted to the study of European-language graphic novels, comic strips, comic books and caricature”. What this appears to mean, in practice, is that articles on American comics are excluded. as papers on both Manga and South American comics are included in the two issues available to the reviewer.

The journal is published twice a year, spring and autumn and comes as a short, slightly over-sized paperback.

The first thing that the outsider notices is that the article titles are almost totally incomprehensible. This is not a journal aimed at a general readership. It took a few journeys to the dictionary to figure out just what was meant by “Instrumentalising Media Memories..” or “A Transtextual Hermeneutic Journey” in the titles of the first two papers, but having noted that, the spring 2019 edition turned out to be a fascinating read.

The opening article is an examination of “Achtung Zelig!“, the title of a graphic novel published in Poland in 1994 written by Krystian Rosenberg with art by Krzysztof Gawronkiewicz and subsequently expanded and republished in 2004. The article examines the book, a grotesque, fantasy set during World War Two dealing with an encounter between a Nazi officer, depicted as a clown/wizard figure with a high cone hat, and a Jewish father and son with blanked out faces.

The article makes a convincing case that the comic is not intended to depict or comment on the real events of World War Two, but rather is an illumination of the distorted memories, legends and state propaganda that coloured Polish memories under the Soviet occupation and, in effect, blanked out the experience of the Jewish people. In effect, “false reporting”, that dangerously distort and make difficult, if not impossible, any proper discussion of the key events that lead to the state of the Polish nation at that time.

The article then goes on to examine other depictions of World War Two, including Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Charlie Chaplin’s film, The Great Dictator – and examines what part they may play in distorting ‘real events’ or be influenced by already existing distortions.

Overall, a fascinating and thought provoking read, that repaid the hard work deciphering the technical language of academic literary analysis.

And it was hard work. Like any other academic discipline, literary analysis has its own vocabulary – one that can be difficult to follow and requires that sentences are examined very carefully.

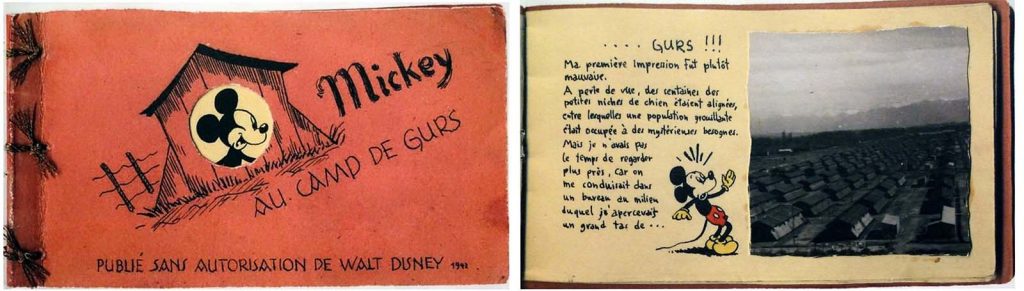

The first article leads directly into the second, an examination of a 1942, satirical comic “Mickey au Camp de Gurs” written by Horst Rosenthal, a German born French cartoonist of Jewish descent. This was a new piece of comic history to me, a pamphlet drawn in the style of a Mickey Mouse book, by a Jewish detainee in an internment camp in the months before he was sent to die in Auschwitz.

It was impossible for me to read this paper dispassionately, the subject matter being so powerful. The contrast between the Disney style art and the horror of the events depicted came across clearly and sent me off to the net to search out versions of the original pamphlet.

With articles on changes in the source of ‘dread’ in German popular culture over time, with concerns moving from atomic devastation to possible environmental collapse, and the use of a particular, racially stereotyped character, in advertising for the Irn Bru soft drink, this edition of the journal was a fascinating, if difficult read for a non-academic.

Its main effect on me, was to lead me to try to find copies of Achtung Zelig! and Mickey au Camp de Gurs and to read, at last, two hugely powerful pieces of comic art, even if I did have to sit with a French to English translation website for the former.

• Auctung Zelig! is out of print, but there is some information about the4 book here on the publisher’s web site. The strip was also serialised in the long-running Polish title AQQ.

• Mickey au Camp de Gurs – available on Kindle in French – was donated to the Centre de Documentation Juive Contemporaine (Centre of Contemporary Jewish Documentation) in Paris by the Hansbacher family in 1978. It was first published in 2014, along with two of Rosenthal’s other comic books he had created while interred in Gurs, by Calmann-Lévy and the Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris, which exhibited the original artwork in 2017. You can also read the comic online here, on Le Figaro web site

The Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics takes an intentionally panoramic view of the world of comics, not just in terms of the material it covers, but in the way that it looks at comics. The aims and scope, printed on the inside of the front cover, state quite clearly that nothing is excluded based on country of origin or genre. “The Journal aims to reflect and encourage the widest breadth of approaches to the comic, as a mass-media medium, and its associated forms,” it’s noted.

The journal, edited by David Huxley and Joan Ormrod, both from Manchester Metropolitan University, certainly appears to live up to those aims.

In the editions I looked at, Volume 10, Numbers 3 and 4, there was an emphasis on papers taking an ‘interdisciplinary view of comics culture, moving away from pure literary analysis, with an additional focus on the difficulty of defining exactly what comics are in a culture where mediums are becoming ever more interconnected.

Articles on viewing the 2016 US election through the lens of Warren Ellis’ Transmetropolitian series and another on the relationship between the ethics of Jesse Custer, John Wayne and the journey to becoming the ‘Ideal Man of the American West’ took a different, and often difficult, look at titles that are more familiar to casual comics fans.

Most accessible, for me at least, was a paper discussing the excesses of the depiction of the human body by Image Comics founders, Todd McFarlane, Jim Lee and Rob Liefeld – and the relationship to the then burgeoning fitness culture. I noted that the author seemed almost defensive about dealing with such popular comics and that would tie in with a prejudice I have about ‘academic’ comics versus popular literature.

The Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics was the most accessible of the three journals in terms of the subject matter covered. I’d read a good number of the comics under examination, but again, it wasn’t an ‘easy’ read for an outsider looking in.

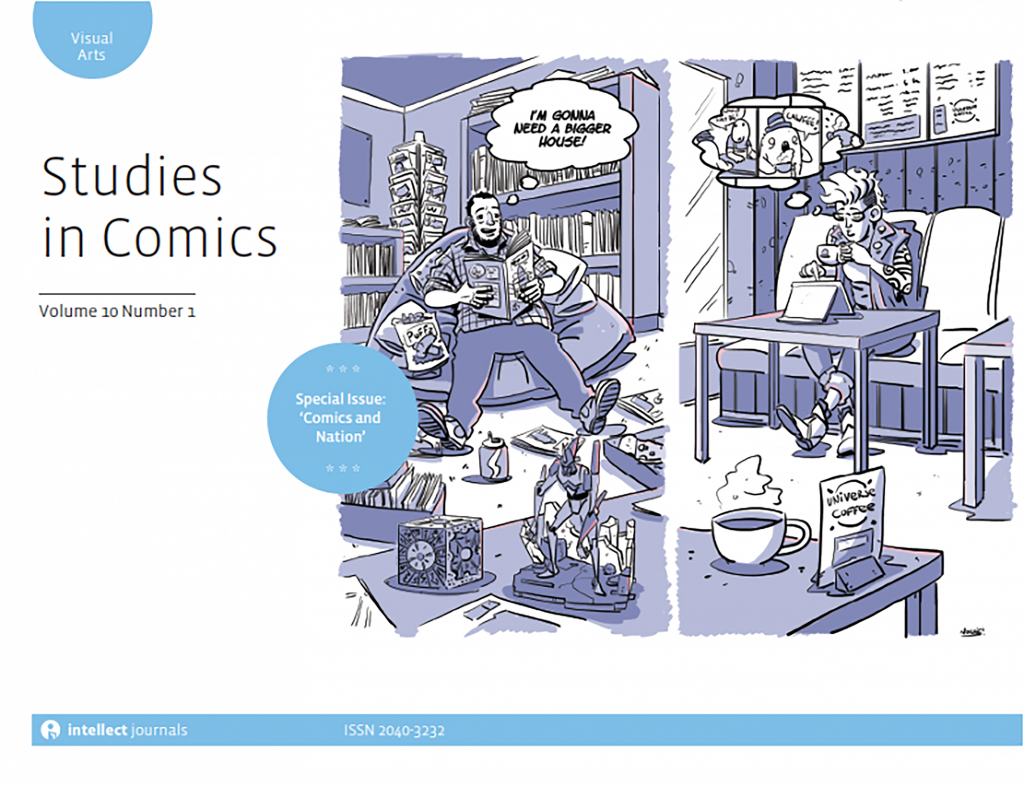

Studies in Comics, edited by Professor Chris Murray from University of Dundee and Julia Round from Bournemouth University is the most striking package of the three journals. Published in landscape format with attractive covers, its interior pages are laid out with one wide margin – perfect to make pencil notes in, I suspect.

Taking the most recent issue to hand, Studies in Comics seems to take a slightly different approach again to its contents. While European Comics Art seemed to extend literary study from prose to comics and The Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics aimed to move way beyond that, Studies in Comics is, perhaps, aimed a little more at the creators of comics than the reader. While consisting mainly of academic papers, it also includes some more accessible material in the form of creator interviews that don’t require such frequent visits to the dictionary to understand.

In volume 10, Issue 2, there are articles on “interactive comics”, “the depiction of silence in sequential narratives” and a fascinating article on podcast dramas and their similarity to comics as mono-sensory mediums.

There is still room for literary analysis, and articles on Moral Ambiguity in 1950’s Superman stories and “sickness, disease and perversion” in Charles Burns’ always disturbing, graphic novel, Black Hole were difficult but fascinating reads, both of which sent me back to the source material with a new perspective.

This issue is rounded out with two interviews, carried out by Julia Round and Jeffery Klaehn, which would be fascinating for anyone with an interest in British comics. The first, with Wilf Prigmore, Group Editor for Girls’ Adventure comics at Fleetway/IPC in the 1970s, is an excellent addendum to books by Pat Mills and Steve MacManus on their time at IPC and Julia Round’s excellent book, Gothic for Girls: Misty and British Comics.

The second, with the late, renowned Batman artist, Norm Breyfogle, covers his working relationships with Alan Grant and his views on some celebrated Batman artists and equally enlightening.

Overall, there was a lot to enjoy and think about in this Journal. I re-read some favourite comics in a new light and even went back over a story I’d written with a fresh pair of eyes. On a totally non-academic note, Studies in Comics was also a pleasure to read.

Academic journals are never easy for the layman. Each discipline has its own vocabulary, and I’m sure that there is much that I have missed or misunderstood in the papers I have read. But each delivered a different perspective on a medium I have been absorbed by for more than fifty years.

European Comic Art led me to discover two very special examples of the art of comics, the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics gave me something new to think about in terms of comics I had read and thought I knew pretty well; while Studies in Comics provided both of the above, plus an insight into the thoughts of creators responsible for some of the comics I’ve read over the years.

These are journals that I would be tempted to go back to, although the biggest issue is with the price. Academic Journals are expensive. Each of these are published twice a year, with the cheapest price for an non-academic subscription to European Comic Art costing £46, for The Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, £38, but according to the website that price is only available for attendees at The Eighth International Graphic Novel and Comics Conference, and for Studies in Comics, £40.

The journals often offer discounted personal subscriptions at conferences and events and with the Coronavirus Pandemic in effect these are likely to be offered more widely. Anyone from outside the academic world who is interested should contact the editors for details of these offers.

Peter Duncan

WEB LINKS

• Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics

* The early work of academics such as Martin Barker, particularly around the “Horror Comics Scare” in the 1950’s should not be forgotten. But Barker’s subject was more about reaction to comics and less about the comics themselves”. The subject of pre-2000 comics’ scholarship should, perhaps, be an article all its own

Peter Duncan is editor of Sector 13, Belfast’s 2000AD fanzine and Splank! – an anthology of strips inspired by the Odhams titles, Wham!, Smash! and Pow! He’s also writer of Cthulhu Kids. Full details of his comics activities can be found at www.boxofrainmag.co.uk

Categories: Comics Education News, Comics Studies, downthetubes News, Features, Reviews

A most worthy article, Peter. It’s nice to see academic work get a mention on DTT. I’m a scholar of comics in translation, so I hope your article will encourage readers to check what’s out there. It would be nice to think that people other than academics might read my occasional scholarly article.