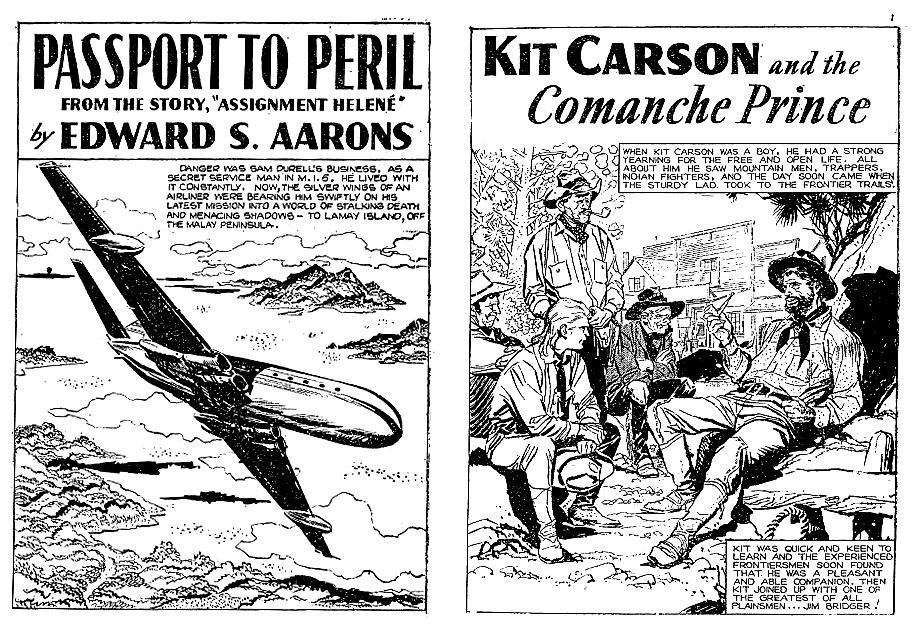

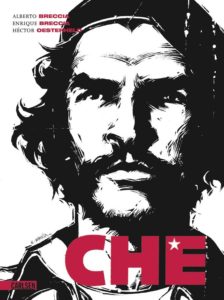

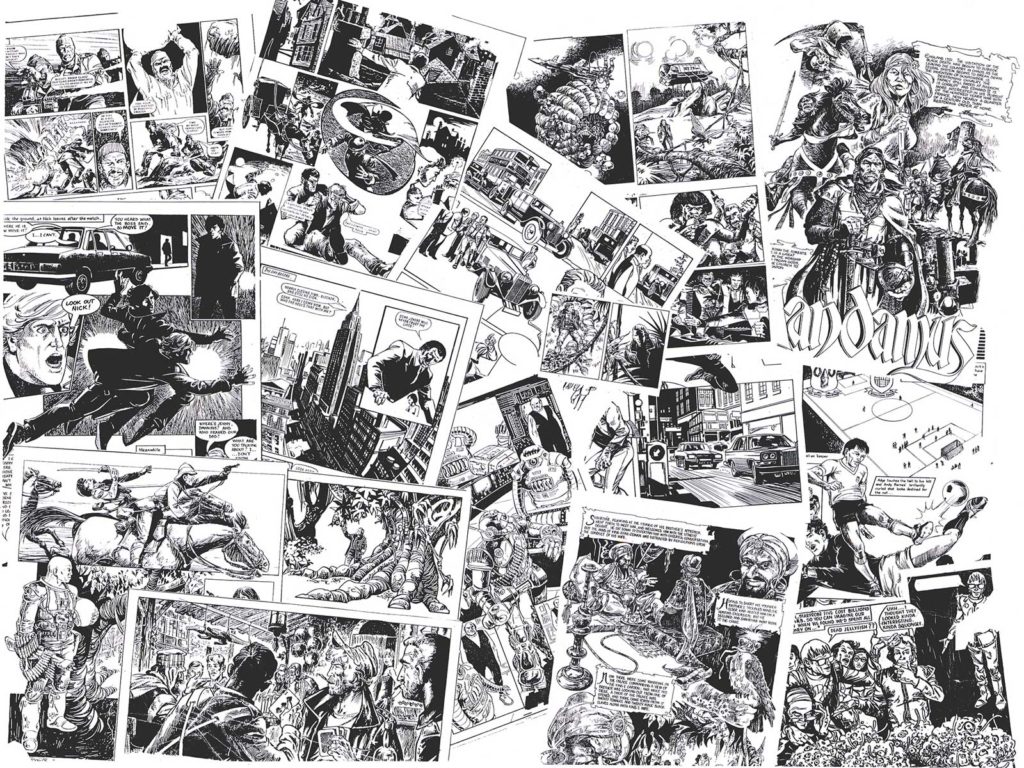

He’s perhaps best known to British comic fans for his work through the Bardon Press Features office in Barcelona for Fleetway Edtions in the 1960s, first on Super Detective Picture Library Number 172 “Passport to Peril” (an adaptation of the novel, Assignment Helene by Edward S Aarons), drawing episodes of “Spy 13” and “Kit Carson” for the Cowboy Picture Library, among other work. But Argentine artist Alberto Breccia, often described as “the master of black and white” is considered one of the most influential creators in comics history. Not only because he was one of the founders of a famous art school (the Instituto de Arte) in 1966, but also for his unique and daring style, which firmly places him at the vanguard of the comics medium. His works – which include a comics biography of Che Guevra (Che, written by Hector Oesterheld), Eternauta and more – are highly regarded.

We’re delighted to present this essay on his work by artist Ron Tiner, over three parts – of which this is the second… you can read Part One here, Part Two here, Part Three here – and read one of his classic stories, in English, here

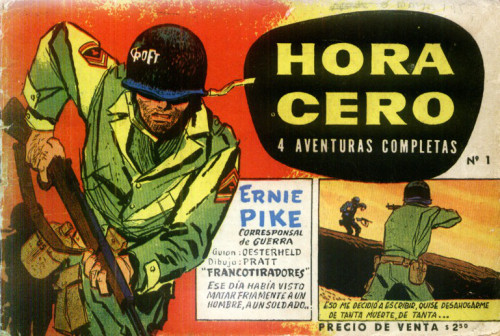

In 1950, Alberto Breccia met the archaeologist/ writer Hector German Osterheld, a political activist of the Peronist JLF, but they would not begin working together until 1958. By this time, both Oesterheld and Breccia had become increasingly frustrated by the triviality of the themes dealt with in the pages of the popular magazines in which their work was being published, and, perceiving a potential in the comic strip medium to treat issues of greater seriousness and significance, Oesterheld set up his own publishing company, Frontera Editorial.

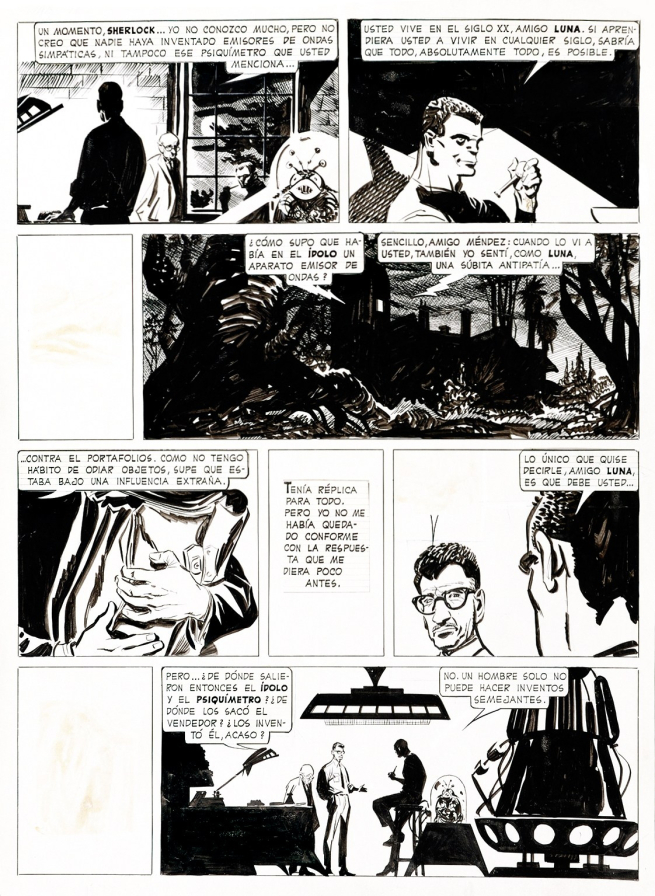

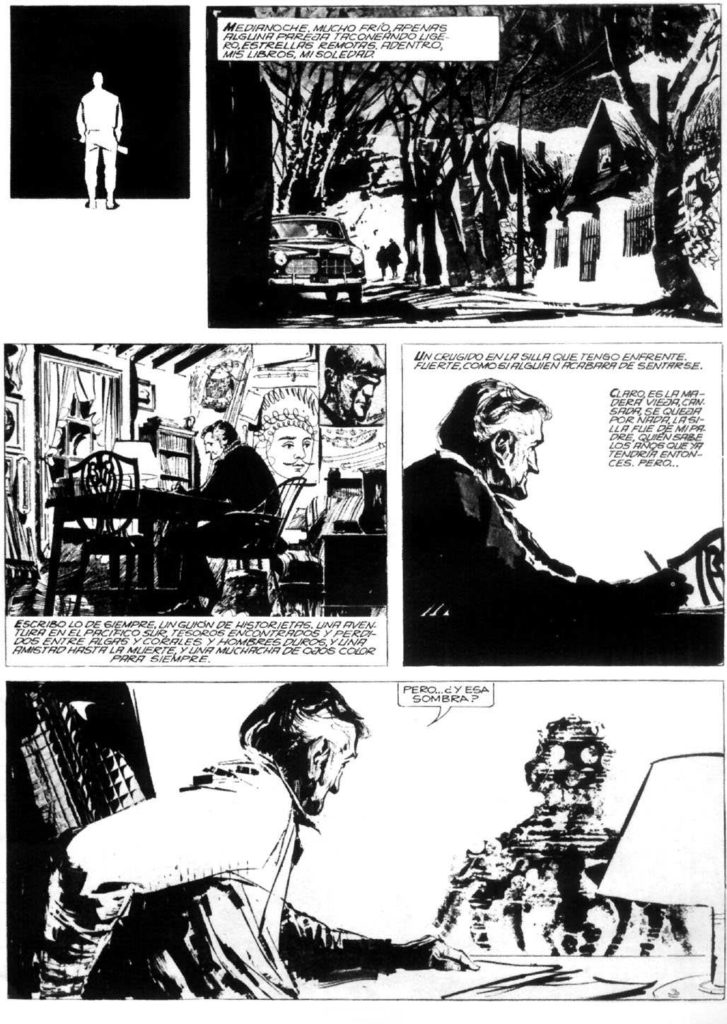

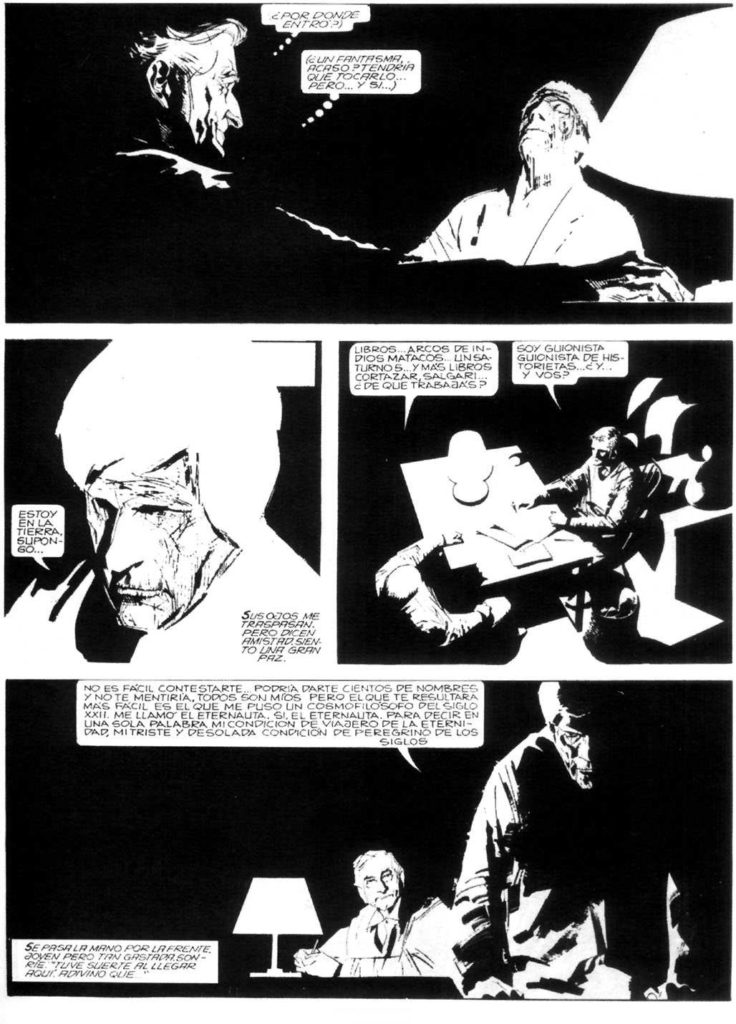

Under this banner, he published the magazine Hora Cero [“Zero Hour”] for which he created a darkly disturbing series of science-fiction stories, Sherlock Time, featuring an enigmatic, interstellar traveller. As was often the case in Oesterheld’s writing, the mysterious central character in these stories is closely associated with what he himself referred to as a “Doctor Watson” figure – a common man who acts as narrator. In this case it is Julio Moon, the purchaser of a big ramshackle house in the oldest part of the city of San Isidro.

In the Argentina of this period the constant threat of being labelled subversive made it essential that references to power and the social order should be presented in terms of metaphor and allegory. Obscurity was essential, and meanings were bound up in complex and oblique references. Thus the dark, unbalanced universe of Sherlock Time struck a chord with the readers of Hora Cero. Breccia’s increasingly moody and expressionist illustrations gave the stories an extra frisson of horror, contrasting the vulnerable humanity of Moon with the deeply shadowed atmospheres in which many incidents in these stories take place.

It was in this series that Breccia’s imagery first began to show the conceptual changes that were to become increasingly evident over the following three decades.

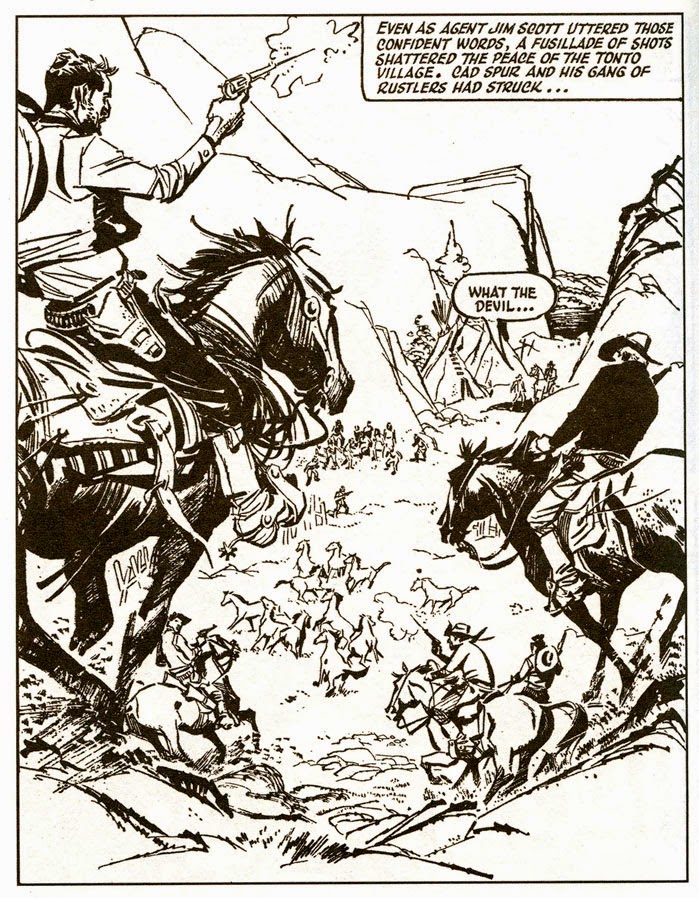

In 1959, he left Argentina to work in England for Fleetway Publications, who were publishing a wide range of digest-sized, 68-page comic books aimed at an adult readership, featuring adaptations of classic and popular literature. The currency exchange rate at that time made the fees paid for such work extremely attractive, and it is evident that he found the new format liberating.

The stories were lighter in tone than those he had illustrated in Argentina, being mainly westerns and World War Two spy stories and he tackled them with a bold, clean, pen-and-brush line, giving some story incidents a dramatic energy along with a light touch of humour and pathos. But in 1961 he was forced to return to Argentina when his wife became seriously ill.

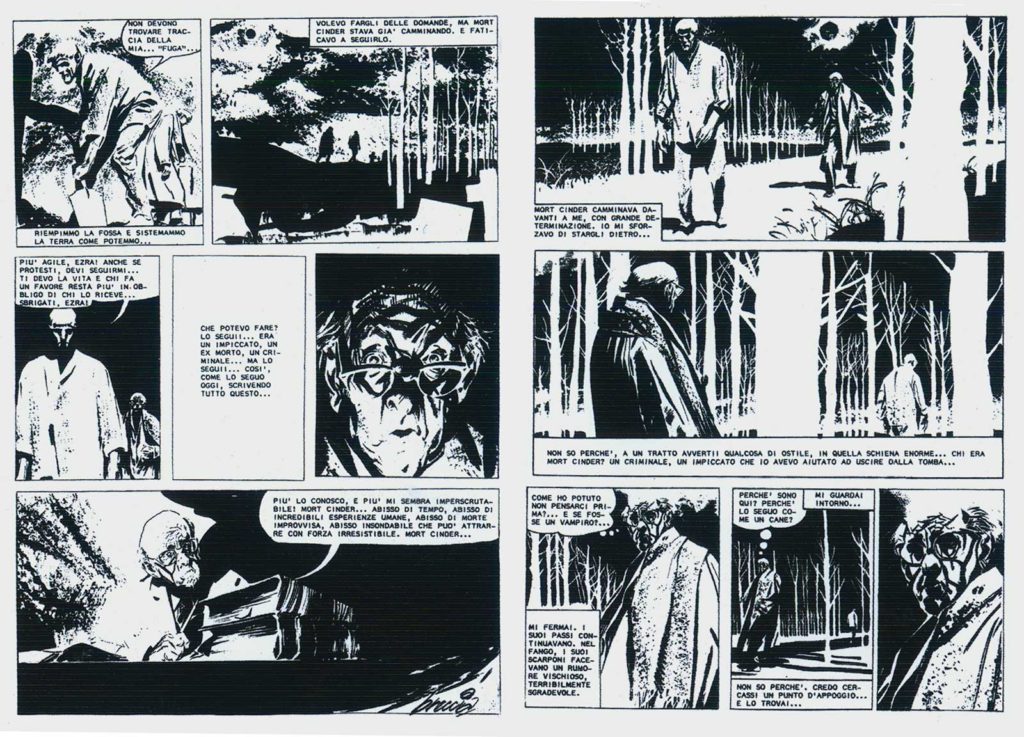

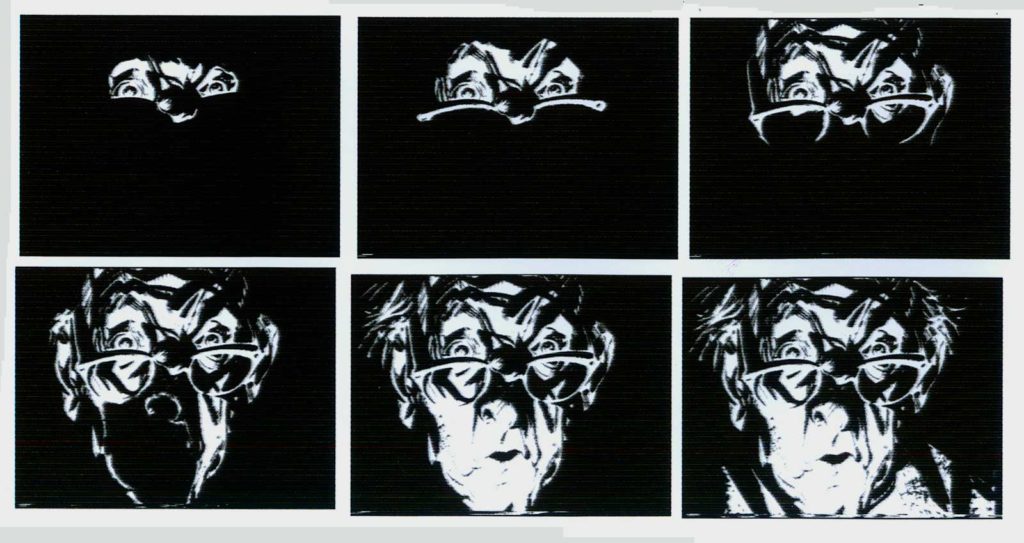

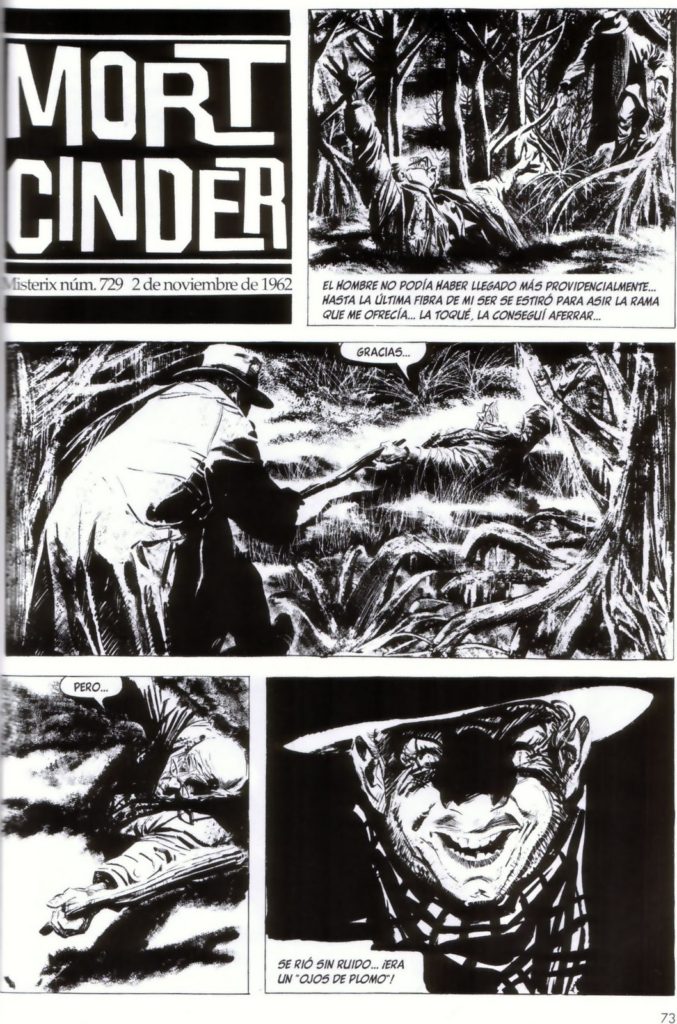

While his wife lay dying in the next room, Breccia worked, to buy expensive medicines and to keep his three children, on another dark and morbid series of stories by Oesterheld entitled Mort Cinder. He opted to portray himself as the leading protagonist in these stories, and the harrowing self-portraits that resulted made extensive use of dramatic lighting effects reminiscent of film noir to achieve a remarkable psychological insight. Deeply depressed by the death of his wife, he became increasingly absorbed in experiments with materials, tools and graphic techniques, exploring new approaches to composition, viewpoint and sequencing in visual narrative.

Pablo de Santis writes, in his preface to the Collihue Editiones 1997 reprint of Mort Cinder, “In these 206 pages we see the successful collaboration of two exceptionally creative artists. Here is the finest work of Oesterheld, given an extraordinary forcefulness by the revolutionary graphic experimentation of Breccia. Here is the meeting of popular culture with a dedicated aesthetic search.”

I shall insert here a brief description of the Mort Cinder stories.

This is a series of ten stories featuring a vulnerable “Everyman” – the antique collector, Ezra Winston – and the mysterious and enigmatic Mort Cinder of the title, who is destined to face death and reincarnation constantly throughout history. Showing the influence of Jorge Luis Borges in its fascination with mirrors and arcane books and with the sense that each character may be no more than the dream of another, each of the stories is presented as a fragment of history, personally experienced by the duo.

The locations for these small fragments of history include a trench in World War One, the deck of a ship involved in the slave trade, The Battle of Thermopylae, The Tower of Babel and others.

In a critical assessment, Laura Vazquez writes: “ This famous work of Oesterheld and Breccia does not present or display chronological history, like a classification of facts and events. On the contrary, Oesterheld’s tacit message is ‘History can be taken apart.’” (Laura Vazquez, Mort Cinder: Memories in Conflict, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 2002)

She goes on: “The immortal figure of Mort Cinder reminds us of El Immortal of Borges, who says, ‘I have been Homer. I will be nobody. Like Ulyses, shortly I shall be everybody: I shall be dead’.” (Ibid)

Breccia’s intense drawings, with their starkly shadowed faces, oddly angled points of view, their fragmented representation of backgrounds and coarsely textured atmospheres provide an appropriate visual setting and offer an extra level of meaning to these intensely bleak and doom-laden stories.

In the film Breccia: Maestro de las Historietas, the artist speaks of the graphic techniques he adopted in Mort Cinder, some of which were recreated for the camera. Most of the work was done using razor blades to carve out areas of white from a prepared black surface. The result was often augmented with brush drawing, finger- and hand-prints, etc. and he goes on to say, “If I feel that the best instrument to use is a hammer, or a pair of bicycle handlebars, then that’s what I will use. I no longer believe that the common pencil and pen are necessarily the best instruments to achieve the effects I need.”

The results became an expressionistic milestone in South American graphic art to which many younger artists still make constant reference today.

In 1966, Breccia, along with Hugo Pratt and Arturo del Castillo, established the Instituto Panamericano del Arte, an art school that was to gain an international reputation, attracting students from all over Latin America.

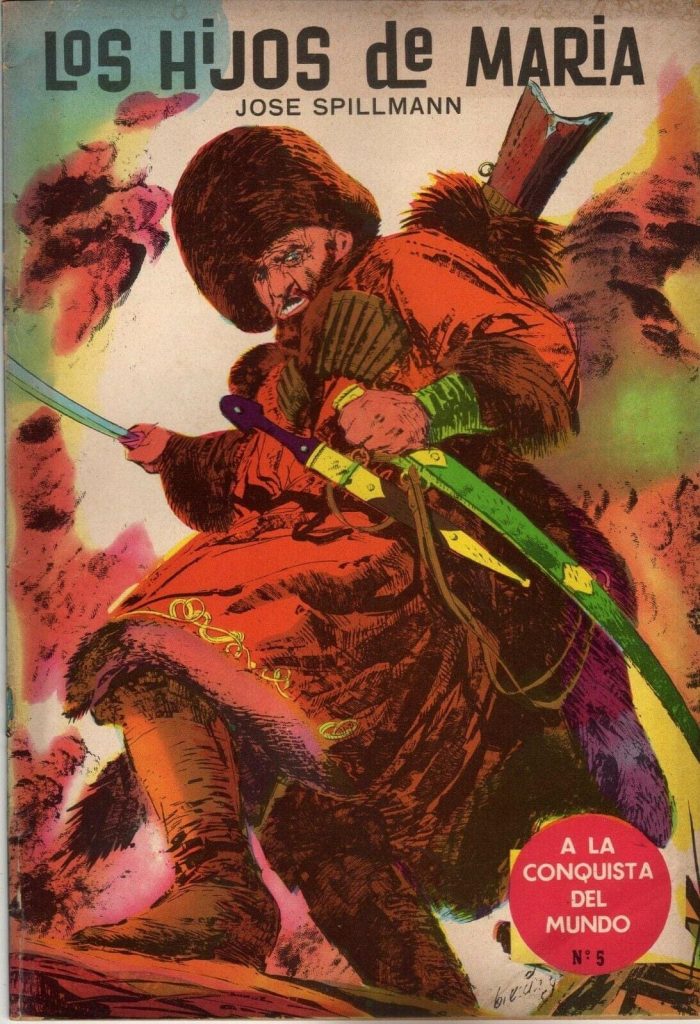

He was one of several artists working on A La Conquistador del Mundo, published by Editorial Esquiú de clara inspiración católica between 1966 and 1967, publishing adaptations of novels and biographies of famous people.

Writers on the short-lived title included Pío Mayo, AS Rios and A. Quintana, who also worked with artists Oscar Carovini, Lito Fernández, José Luis García López and J. Zahlut.

But he maintained his association with Oesterheld, and their next collaboration was El Vida di Che (“The Life Of Che” (Guevara)), in 1968, a project that was to haunt them both for many years and to have mortal consequences for the writer. This was to have been one of a series of biographies of leading figures in South American history, but only one more was ever produced: Evita: Vida y Obra de Eva Peron (“Life and Work of Eva Peron”), published by Doedytores in 1970.

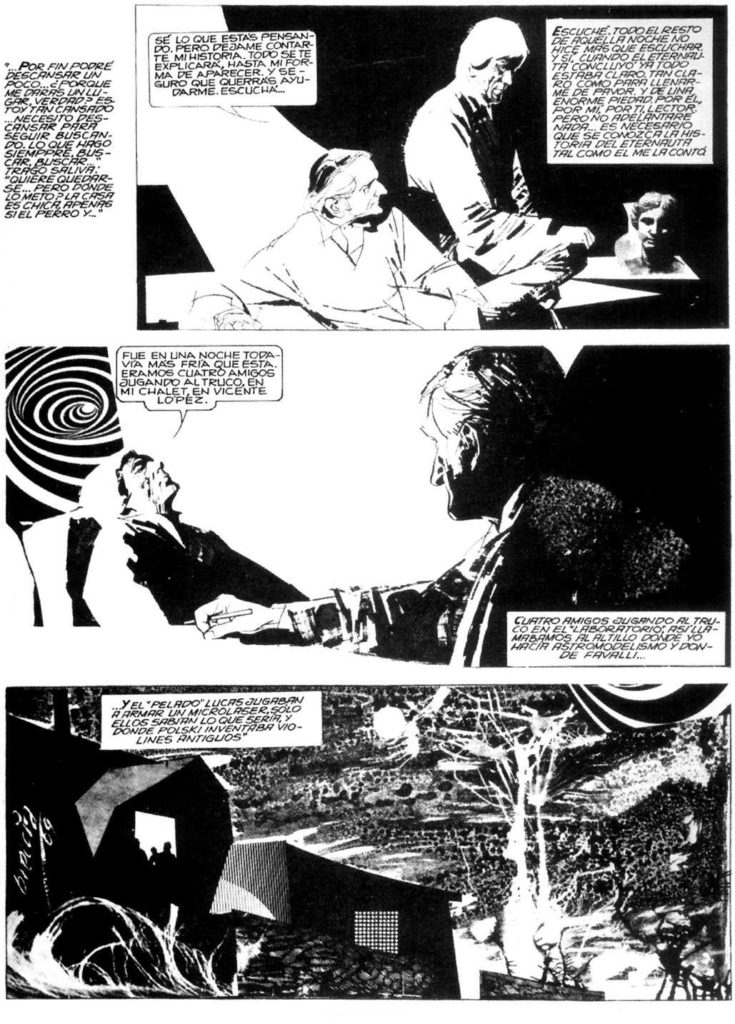

This was followed in 1969 by El Eternauta (“The Eternaut” – i.e. one who travels through eternity) in which Oesterheld returned to the theme of the manipulatable quality of time in fictions.

The first series was illustrated by Francisco Solano Lopez, and although it was popular with Hora Cero’s readers,Oesterheld himself was discontent with the literal rendering that the artist gave it, and wrote a sequel for Breccia, which was published in the periodical Gente.

In the interview already quoted, Breccia said, “Oesterheld was not a scriptwriter – he did not consider summarising in any way. With him, the artist has to do all the adaptation: it is necessary to cut the text, and to change the presentation. El Eternauta had an enormous text – far too much for this medium, otherwise the result would have been far too heavy.” (Bang Magazine No 10, 1973).

The published version was, nevertheless, still textually very dense, in spite of what Breccia says here.

The first part of the story was written just after the overthrow of the Peronist government by the ferocious military junta in 1955, and tells the story of Juan Salvo [which translates as “Safe Juan”], a typical Peronist man: hardworking, middle-class, and with a typical family, who meets with his friends in an attic and they talk nostalgically of the feelings of freedom that they have lost. As Laura Vazquez puts it: “Juan (and Juans always correspond to universal stereotypes) has no conflicts in his life. He is a middle-class man, surrounded by mediocrity” (Laura Vazquez: “Who is safe, Safe Juan? Another Reading of El Eternauta.” Universidad de Buenos Aires, 2003) He is given an opportunity to travel through space and time, but after many vicissitudes, he learns that Earth is to be destroyed and chooses to return to his family and home to await the final destruction. The allegorical references to the political situation in the Argentina of the time are obvious.

In this sequel, Oesterheld, who had now begun to build an association with left-wing militants, wrote sequences in which the people of the earth form resistance groups in attempts to fight against the invaders. Breccia resorted to an even more diverse range of experimental graphic techniques than in his Mort Cinder, giving it a disjointed and morbidly atmospheric visual rendering, but the readers of Ora Cero found it impenetrable and, perhaps inevitably, Solano Lopez was re-engaged. But the rewritten story now featured a future Argentina governed by a terrible dictatorship – a very dangerous subject to tackle in the climate of state terror that subsisted then.

In 1970, the author, along with his four daughters, would join the guerrilla group Montoneros, eventually to be arrested and secretly executed by the Armed Forces. When the Italian artist/journalist, Alberto Ongaro attempted to make enquiries about his disappearance in 1979, he is said to have received the eerie reply: “We did away with him because he wrote the most beautiful story of Che Guevara.”

The Life of Che did not find a publisher in Argentina but it was published in Chile, and news of it had reached the US embassy. Breccia was approached to draw a life of John F Kennedy in a similar way, but the project was never to come to fruition.

The secret police seized the Che artwork and destroyed it, and when the printer who had provided the artwork proofs was seized by the secret police and assassinated, Breccia buried the proofs in his garden, expecting at any moment to be arrested…

Ron Tiner’s essay on Alberto Breccia has been published in three parts on downthetubes

Part One | Part Two | Part Three

• Read one of his classic stories, in English, translated by Ron, here

[divider]

Web Links

• Jose Muñoz takes us through an exhibition of originals of Alberto Breccia

• There’s more on “Sherlock Time” here on the Spanish Sherlock Holmes web site 221B

• The Polish web site Random Act of Stupidity assesses Mort Cinder in more detail here

• The Spanish web site Comic Historietas offers a side by side presentation of the Spanish and Italian versions of the final Mort Cinder story, The Battle of Thermopylae, for fans to decide which version to hunt down

• Tebesosfera: Enrique Breccia. the man who drew Che (in Spanish)

• The Spanish web site superman.marianobayona offers this study of El Eternauta and the different approach to the project by Breccia and Lopez

• For more on the life and work of Alberto Breccia, who died in 1993, visit his official web site: www.alberto-breccia.net

• Amazon’s Alberto Breccia Page

• There is also a profile of Alberto Breccia here on the Dan Dare Info web site and a guide to his British comics work here on the UK Comics Wikia here; this brilliant Spanish comics blog, Deskartes, also features a number of pages of Alberto’s British work, supplied by David Roach

• Comics creator Sarah Horrocks has written several articles about Alberto Breccia on her “73” – read them here

Books

Published by Fantagraphics, this seminal Argentinian science fiction graphic novel was originally released as a serial from 1957-59. Juan Salvo, its inimitable protagonist, along with his friend Professor Favalli and the tenacious metalworker Franco, face what appears to be a nuclear accident, but which quickly turns out to be something much bigger than they imagined.

El Eternauta, Daytripper, and Beyond (World Comics and Graphic Nonfiction Series)

by David William Foster, University of Texas Press

Due for release in October 2016, El Eternauta, Daytripper, and Beyond examines the graphic narrative tradition in the two South American countries that have produced the medium’s most significant and copious output. Argentine graphic narrative emerged in the 1980s, awakened by Hector German Oesterheld’s groundbreaking 1950s serial El Eternauta.

After Oesterheld was “disappeared” under the military dictatorship, El Eternauta became one of the most important cultural texts of turbulent mid-twentieth-century Argentina. Today its story, set in motion by an extraterrestrial invasion of Buenos Aires, is read as a parable foretelling the “invasion” of Argentine society by a murderous tyranny. Because of El Eternauta, graphic narrative became a major platform for the country’s cultural re-democratisation.

In contrast, Brazil, which returned to democracy in 1985 after decades of dictatorship, produced considerably less analysis of the period of repression in its graphic narratives. Serious graphic narratives such as Fabio Moon and Gabriel Ba’s Daytripper, which explores issues of modernity, globalisation, and cross-cultural identity, developed only in recent decades, reflecting Brazilian society’s current and ongoing challenges.

Besides discussing El Eternauta and Daytripper, David William Foster utilises case studies of influential works – such as Alberto Breccia and Juan Sasturain’s Perramus series, Angelica Freitas and Odyr Bernardi’s Guadalupe, and other s-to compare the role of graphic narratives in the cultures of both countries, highlighting the importance of Argentina and Brazil as anchors of the production of world-class graphic narrative.

Mort Cinder, Tome 1 : Les yeux de plomb (French) Hardcover

by Hector Oesterheld, Alberto Breccia

French edition, published in 2004

La Tecnica Del Fumetto

Published in 1982, La Tecnica Del Fumetto features the work and techniques of of Breccia alongside numerous other articles. The book is in Italian and may be hard to track down. There is a little more information here on Google Books

[divider]

About Ron Tiner

Ron Tiner is a comics artist, illustrator, author and educator. In the mid-1970s, he gave up an art teaching post to draw comics. He drew Powerman for Pikin Publications, Spring-Heeled Jack and many other series for for DC Thomson’s Hotspur, worked with Carlos Ezquerra on Major Eazy and Mike Western on HMS Nightshade along with other series for IPC’s Battle Action, 2000AD, StarLord, and other titles. I

n the 1980s he adapted six of Enid Blyton’s “Secret Seven” stories as graphic narratives for Gutenburghus, John Cleland’s Fanny Hill and The Arabian Nights for Escort and for two years drew the football strip Canon for EMAP’s Match Weekly. He also drew several features for the humour titles Oink! and Brain Damage, a five-book John Constantine story for DC Comics’ Hellblazer and one single episode of George & Lynn for The Sun newspaper.

In the late 1980s he turned to book and magazine illustration, working for Oxford University Press, Penguin, Usborne etc., producing illustrations for books by Washington Irving, Charles Dickens, Joseph Conrad, Thomas Hardy, John Buchan, Frederick Forsythe, Arthur Conan Doyle and many others. His illustrations have appeared in The Daily Telegraph, The Guardian, The Observer, The Financial Times and Punch Magazine.

He contributed articles to the second edition of The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (1993) edited John Clute and Peter Nicholls, and was a Contributing Editor to The Encyclopedia of Fantasy (1997) edited by John Clute and John Grant.

In the mid-1990s he was invited to construct a course in narrative and sequential illustration for Swindon College of Art, where he taught for seven years. In 2006 he gained a Masters’ degree from Falmouth University, specialising in comics theory and narratology.

He is the author of Figure Drawing without a Model, (1992), The Encyclopedia of Fantasy and Science Fiction Art Techniques (written in collaboration with John Grant) (1996), Mass: The Art of John Harris (2000) and Drawing from your Imagination, (2008). All of these books have been published in several different languages.

Ron is currently at work on a major illustrated Sherlock Holmes project – among other things.

The founder of downthetubes, which he established in 1998. John works as a comics and magazine editor, writer, and on promotional work for the Lakes International Comic Art Festival. He is currently editor of Star Trek Explorer, published by Titan – his third tour of duty on the title originally titled Star Trek Magazine.

Working in British comics publishing since the 1980s, his credits include editor of titles such as Doctor Who Magazine, Babylon 5 Magazine, and more. He also edited the comics anthology STRIP Magazine and edited several audio comics for ROK Comics. He has also edited several comic collections, including volumes of “Charley’s War” and “Dan Dare”.

He’s the writer of “Pilgrim: Secrets and Lies” for B7 Comics; “Crucible”, a creator-owned project with 2000AD artist Smuzz; and “Death Duty” and “Skow Dogs” with Dave Hailwood.

Categories: British Comics, Comic Creator Spotlight, Creating Comics, Features

Remembering Jon Haward: A Tribute by Tim Perkins

Remembering Jon Haward: A Tribute by Tim Perkins  Catching up with the Comics Laureate! An interview with Bobby Joseph

Catching up with the Comics Laureate! An interview with Bobby Joseph  Comic Creator Spotlight: An Interview with Commando and Doctor Who writer Rossa McPhillips MBE

Comic Creator Spotlight: An Interview with Commando and Doctor Who writer Rossa McPhillips MBE  In Memoriam: Illustrator, Designer, Publisher and Comic Creator Garry Leach

In Memoriam: Illustrator, Designer, Publisher and Comic Creator Garry Leach