Andrew Ross, Graduate Tutor and Lecturer in Film at Northumbria University, discusses how Harley Quinn is not just a side-kick to The Joker, but is now a multi-platform anti-hero….

The joke’s on Batman this year. Fans of the Caped Crusader usually celebrate Batman Day on 23rd September, but this year his thunder has been stolen by a young woman wielding a giant mallet and wearing a broad grin. On 11th September 2017, Harley Quinn turns 25 years old – and the former psychiatrist who turned to the dark side in 1992 as a sidekick to The Joker celebrates her silver anniversary as a fully rounded DC Comics multi-platform villainess.

But who is Harley Quinn – and why is a relative newcomer being granted a privilege usually afforded to the most celebrated of DC’s comic book stable? Simply put, she is a phenomenon who, since beginning life as a background stooge, has routinely matched, and occasionally outsold, the publisher’s Golden Age trinity of Batman, Superman and Wonder Woman to become the official fourth pillar of DC.

But the character’s significance reaches far beyond the printed page. Harley Quinn’s success highlights that agile consumer content is not necessarily based upon genre or legacy – but upon fluidity of content. For her audience, Harley Quinn combines the pleasures of narrative with those of participation – in other words, she is not merely a comic book character to consume passively. She is an experience.

Quinn begins

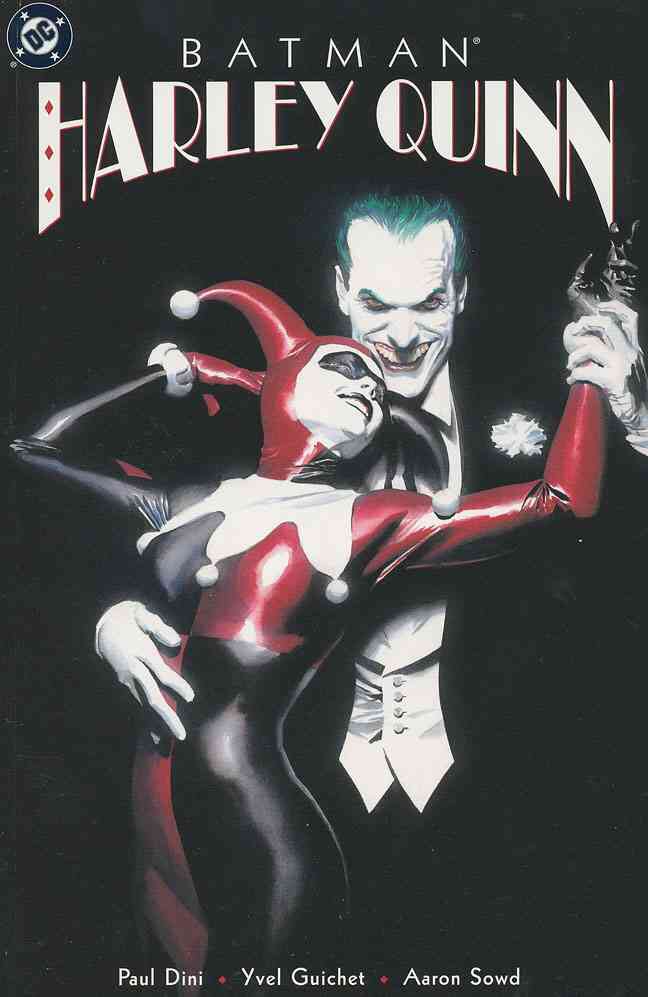

The story begins with a party. It is 1992 and Paul Dini – a screenwriter for the animated Batman series – is devising a scene in which a villain needs to deliver a giant cake to Commissioner Gordon in which lurks The Joker. He invents an exotic accomplice to perform the act: Harley Quinn. And so, a star is born.

A baby-voiced moll in a black and red jester’s costume, Harley Quinn may look like a clown – but she kicks like a mule and, when cornered by Batman, pulls a knife when the hero’s back is turned. More vicious than femme fatales Catwoman and Poison Ivy, Harley Quinn is also revealed in time to be something that they are not – a victim who wants out.

In 1994, Batman Adventures: Mad Love, a non canonical spin-off comic from the animated series, was the first to relate the story of how infatuated psychiatrist Harleen Quinzel became seduced by the incarcerated Joker into helping him escape, only to find herself trapped in the prison of an abusive relationship ever since.

A unique example of a key Batman storyline which originated outside the comic book canon, Mad Love’s controversial influence spread so widely across multiple platforms (the animated series, comic books, the Arkham Asylum videogames, the film Suicide Squad) that it quickly became embedded into the fabric of the DC multiverse.

But while containing the root of Harley Quinn’s appeal, Mad Love also exposes her key difference: Harley Quinn is not a comic book character at all, she is a television one – and her relationship with the Joker is not one defined by the dramatic tensions of crime fiction but a twisted version of the “Will they? Won’t they?” plot line seen across soap opera and romantic comedies.

Her unusual origin on screen therefore meant that when Harley Quinn and her backstory became eventually absorbed by the main comic book series, tropes of TV melodrama and sitcom flowed into the DC canon – and with them entirely different audience methods of consuming content.

Comic book chameleon

My research investigates the construction of media narratives as vehicles for fulfilling audience need – and when examining the Harley Quinn story experience I was struck by how multivalent the character actually is.

While the values of stable mates Superman, Batman and Wonder Woman were codified within a few appearances, Harley Quinn can appear to be in flux 25 years on. Pick up a Batman comic in the 1940s and one from the 1980s and the values of the character remain the same with only the cultural prism through which the author views those values having changed. But over the last year alone, there have been at least six different versions of the Harley Quinn character presented to the audience across comic books, video games and film with almost no continuity of tone, content or genre between them.

This could be an indicator of trouble for a property – how can an audience make sense of the various texts if they all clamour for attention with different signals simultaneously? But it appears that mutability for Harley Quinn is the essence of her popularity. While the rest of the DC canon remain shackled to their comic book roots, and therefore can only appear as either straightlaced or parodic, Harley Quinn is a transferable property created beyond the page and able to be moulded to whatever genre or tone the creators and the audience desire.

Best friend gone bad

In the most telling storyline of recent times, Harley Quinn happens upon the amnesiac super-heroine Power Girl and pretends to be her sidekick for no other apparent reward than the opportunity for a fresh start. And, although from her very first appearances in the animated series, Harley Quinn is someone who has always been trying to escape her past, the Power Girl storyline illustrates that the character also has the self awareness to understand that this task is Sisyphean.

Super heroes such as Power Girl may deliver a vicarious thrill of empowerment to the audience but they are also untouchable paragons of virtue. Harley Quinn’s potency, is her ability to reach out to the audience and say: “It’s OK – I’m a mess, too.” Not an idol, but a friend.

Harley Quinn’s story may have begun with her breaking into a party, but I believe the Harley Quinn experience is a party to which we are all invited – a party which delivers a sense of belonging and an tragicomic acceptance that we are all at the whim of the fates together. The Justice League are heroes but they are also elitists who sit on a pedestal. Harley Quinn is a killer and accomplice to unspeakable deeds – but at least she’s one of us.

• This article was originally published on The Conversation. To read the article click here

Harley Quinn, Batman copyright DC Comics

The founder of downthetubes, which he established in 1998. John works as a comics and magazine editor, writer, and on promotional work for the Lakes International Comic Art Festival. He is currently editor of Star Trek Explorer, published by Titan – his third tour of duty on the title originally titled Star Trek Magazine.

Working in British comics publishing since the 1980s, his credits include editor of titles such as Doctor Who Magazine, Babylon 5 Magazine, and more. He also edited the comics anthology STRIP Magazine and edited several audio comics for ROK Comics. He has also edited several comic collections, including volumes of “Charley’s War” and “Dan Dare”.

He’s the writer of “Pilgrim: Secrets and Lies” for B7 Comics; “Crucible”, a creator-owned project with 2000AD artist Smuzz; and “Death Duty” and “Skow Dogs” with Dave Hailwood.

Categories: Comics Studies, downthetubes Comics News, downthetubes News, Events, US Comics

Telling Your Research Story Through Comics – Special Webinar announced by University of California

Telling Your Research Story Through Comics – Special Webinar announced by University of California  SLJTeen Live! ponders future of storytelling today – a comic creators-packed live virtual event

SLJTeen Live! ponders future of storytelling today – a comic creators-packed live virtual event