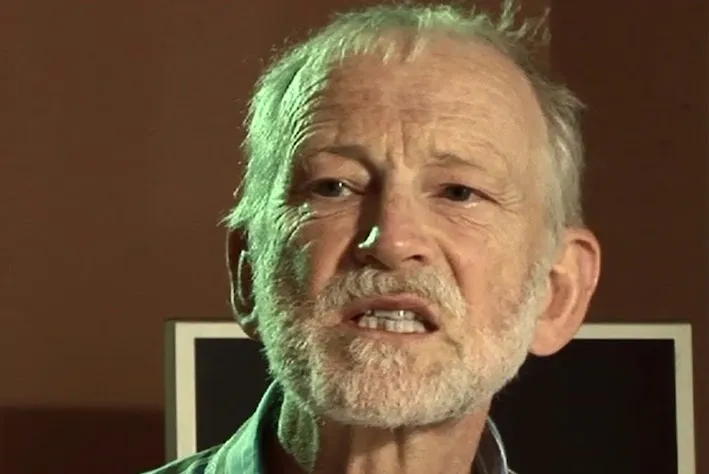

It was with deep regret and no little sadness that I read of the death of Martin Barker, Emeritus Professor of film and television studies at Aberystwyth University.

Born in 1946, Martin received an undergraduate in Philosophy from the University of Liverpool in 1967 and a D.Phil from UWE. Martin’s academic career spanned posts at Bristol Polytechnic (aka The University of West of England), the University of Sussex and the University of East Anglia.

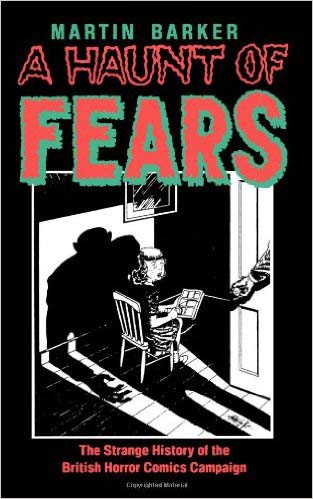

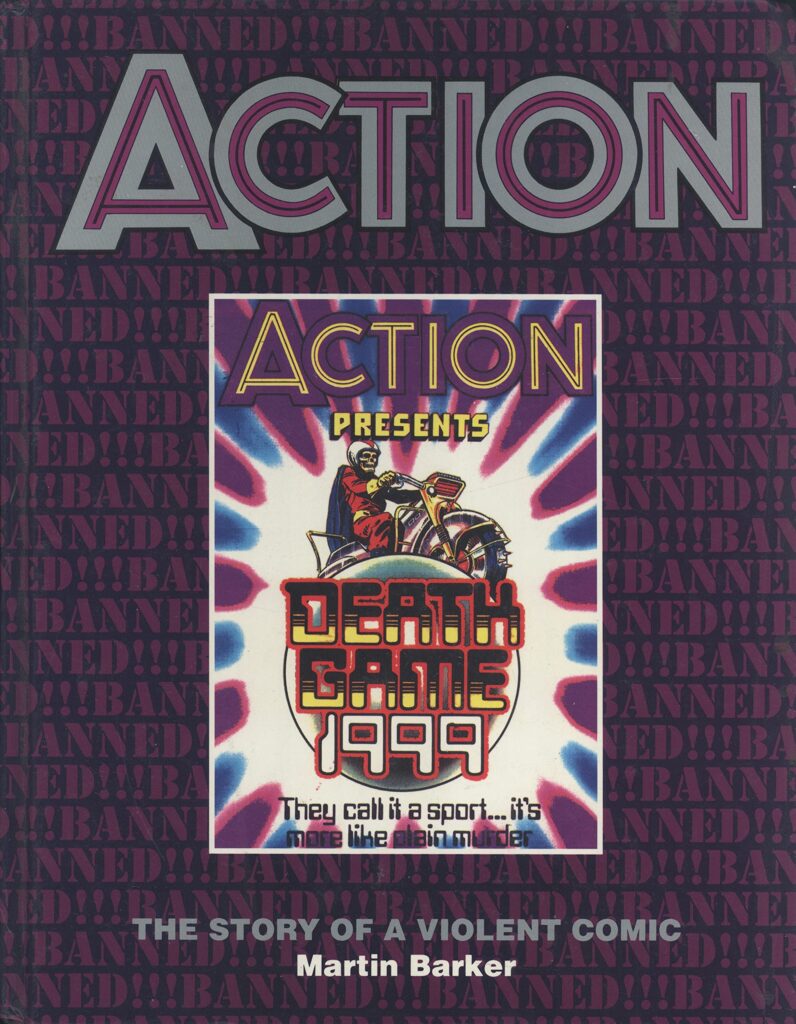

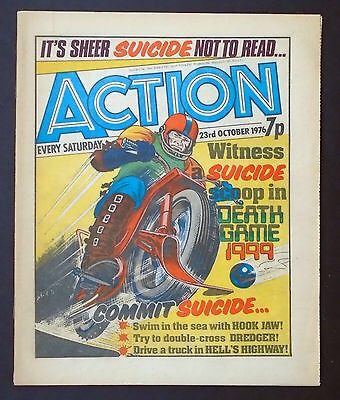

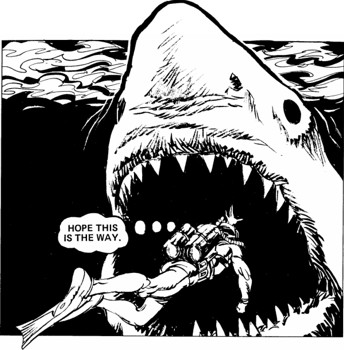

Martin is probably best-known in the comic book community for A Haunt of Fears: The Strange History of the British Horror Comics Campaign (1984), Comics: Ideology, Power and the Critics (1989) and Action: The Story of a Violent Comic (1990).

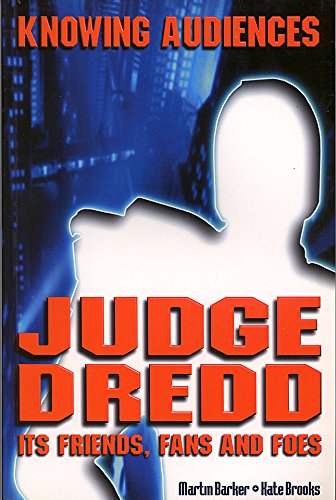

Martin’s studies of media audiences included Knowing Audiences: Judge Dredd – Its Friends, Fans and Foes, co-authored by Kate Brooks (1989), Watching The Lord of The Rings: Tolkien’s World Audiences (2008), co-authored with Ernest Mathijs, and, more recently, research on audiences for sexual violence in cinema. After his retirement, in 2013, Martin continued to edit Participations, The International Journal of Audience & Reception Studies, and co-authored an introduction to an issue dedicated to The World Hobbit Project in which he participated.

Professionally and personally, I met Martin in a number of contexts. He was on the re-validation panel for the prestigious degree in Communication Studies at The Polytechnic of Wales, on which I taught.

Martin accepted my first academic work, a populist piece on the Teenage Mutant Ninja turtle craze for the first issue of the Magazine of Cultural Studies and was supervisor of my equally short lived Phd on globalisation in the animation industry. I felt honoured to be asked by Martin to run a course on analysing visual media at the University of Sussex. Socially, I attended his house warming party in Brighton and he, in turn, attended my chaotic fortieth birthday party.

I was never taught by Martin, but his former students have been quick to sing his praises. The organisers of the Abertoir – The International Horror Festival of Wales posted, “We were all educated by Martin as students, worked with him as scholars and professionals, and were honoured by his presence as a guest at Abattoir as a key figure in UK film history. Martin was as generous and supportive in his teaching as he was rigorous in his scholarship. That ethos and influence will never be forgotten”.

Sadly, values in society are often reflected in academia, and Martin occasionally butted heads with those who saw no value in materials such as science fiction, horror films, and comics. Reflecting on a failed bid to study audiences and academic reception of Ridley Scott’s Alien, Martin recalled, “what narked me hugely was that one of the evaluators pretty much dismissed the bid with a comment that this wasn’t the kind of film that was worthy of serious attention.”

Universities’ timidity in the face of overbearing interpretations of research ethic and legal cowardliness brought its own dismissal of Martin’s work, “I have a very clear memory of an idiot of a Pro-Vice Chancellor, when I was asked to explain what my early ‘horror comics’ research had involved, throwing back, “Yes, and if you were doing that now, we wouldn’t let you.”

The research, published as The Haunt of Fears (1984, Pluto Press), is an exemplary work of investigation. Martin critiques the arguments around The Seduction of the Innocent: Fredric Wertham’s scaremongering work of psychoanalysis which suggested children were being harmed by comic book stories of violence, crime and homosexuality. Of particular interest for Martin was the role of the British Communist Party (BCP) in Britain’s horror comic ‘witch-hunt’. Martin discovered that, in Britain, the BCP’s commitment to “Anti-Americanism” led them to instigate the campaign against horror comics as examples of the Americanization of British culture.

Reflecting on the Pro-Vice Chancellor’s words, it is hard to see where their objection lay. Was it because Martin named his informants? Was it that he recorded interviews with his participants? Or was it that the subject matter and Martin’s debunking of ‘media effects’ was so challenging that even the Pro-Vice Chancellor recoiled in horror! What toxic materials might even now lurk in Universities’ Library vaults waiting to seduce young academics?

Reflecting on his own research career, influence and legacy, Martin noted “I suspect I am best known for: my work on issues around censorship and censorship campaigns, moral scares, and issues of ‘media violence’ and its ‘effects’ and so on.”

Martin, along with fellow psychologist Dr Guy Cumberbatch, Director of the Communications Research Group, Aston, had offered themselves as contacts for the press and television with the aim of countering scaremongering voices that attributed violence in society to the effects of film, TV and video. For example, Martin and Cumberbatch thoroughly demolished the foundations of Elizabeth Newson’s report “Video Violence and the Protection of Children” (1994), commonly known as “The Newson Report”, that informed MP Robert Alton’s Criminal Justice and Public Order Act, 1994. This gave the British Board of Film Classification the job of regulating video content deemed harmful to children.

Newson, a respected Developmental Psychologist, had claimed that video violence contributed to the murder of teenager Suzanne Capper by her classmates and suggested that the girl’s killers had listened to rock music from the soundtrack of the horror film Child’s Play. This echoed earlier claims by the press that the killers of James Bulger were motivated to murder after watching Child’s Play 3. But even the Police found that there was no evidence for any of these claims.

In the collection Ill Effects: The Media Violence Debate (2001), Martin criticised the intent, moral concerns and methodology underpinning Newson’s report, noting, “Most of us have no chance to check claims in cases like this. We are therefore dependent on how the facts are presented to us in the media…They speak in a vocabulary that we recognise. So even when refuted, such cases don’t go away. They linger like ghosts, always half-alive to ‘explain’ the next ‘inexplicable’. Long after the link in the Bulger and Capper cases had been thoroughly disproved; journalists and others were happily repeating them as if they were established truths”.

Martin’s work consistently stood against granting power to pictures. (Simply put: imagine that you are driving and your car stops at a red light. What stopped the car? A) The red light or B) you? (warning: more complex explanations than a or b are available). He argued “We need a theory that…will be quite different from the usually assumed view that the media work ‘to take us over’ and make us helpless in the face of their messages”.

Martin was a socialist throughout his adult life and a one-time member of the International Socialists (IS) group. In academia, his work drew on the tradition of “English Marxism”, an approach which emphasised historical research on the formation of the English working class and their active ‘agency’ in specific moments of class conflict.

There are also clear parallels between Martin’s perspective and Geoffrey Pearson’s Hooligan: The History of Respectable Fears (1983). There, Pearson had argued that contemporary fears about “hooligans” and street crime rested on a myth of Britain’s idyllic past and debates around “law & order” masked the real sources of conflict – poverty, ill health and class inequalities – and only succeeded in demonising the working class.

Parallels between Martin’s and Pearson’s perspectives are probably most obvious in Martin’s book The New Racism (1981). Martin noted that, where racism used to be based on imputed biological differences between so-called ‘races’, the Right was now casting immigrants as a threat to British culture. Barker traced Tory and Nazi rhetoric about the historical unity of a British National culture in the 70s and 80s back to the foundations for cultural racism in the thought of the Scottish Englightenment philosopher David Hume.

The Right were summoning spectors of an imagined, mythical, British identity just at the moment that British society was experiencing radical change, shades of Marx. To Martin, these ‘spirits of the past’ and bogus claims of irreconcilable cultural differences between Britain’s diverse population were an obvious distraction.

Turning to the crusade against Horror comics, Martin found a continuity with middle-class Victorians’ censorious reaction to so-called “Penny Dreadfuls” and late Nineteenth Century condemnation of “Freak Shows”. These too were based on myths of, for example, childhood and implicit claims about the harmful effects of looking and reading.

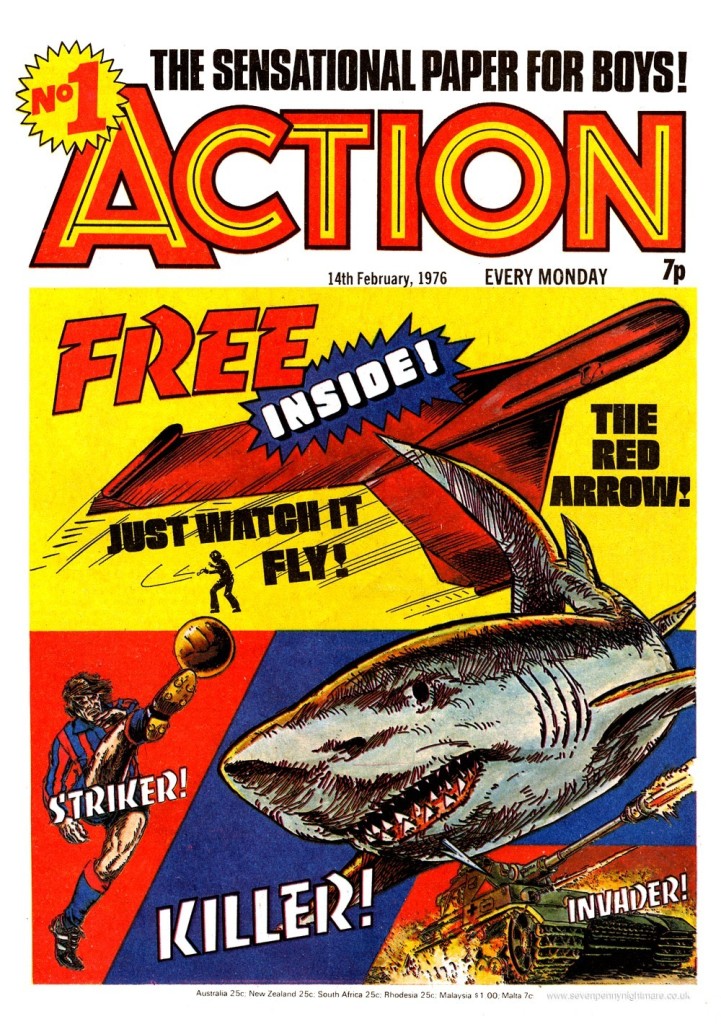

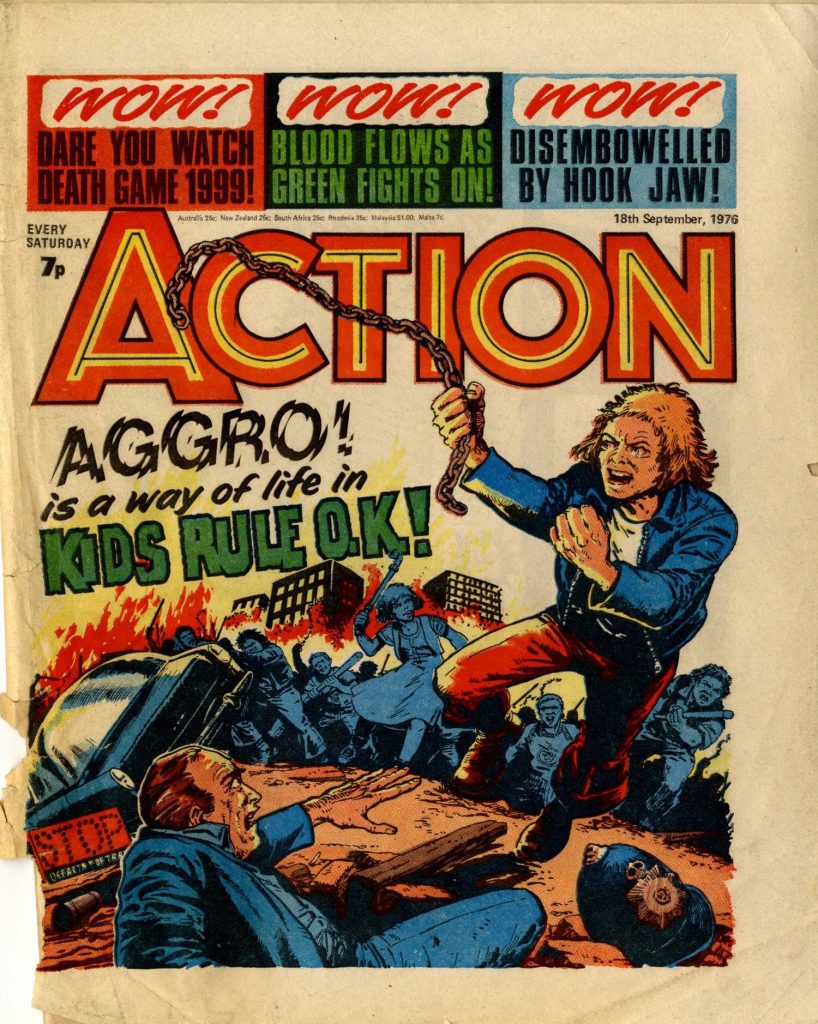

Martin saw moral scares, past and present, as revealing the way popular culture exemplified conflicting social relations. Discussing the British comic, Action, in an interview with MIT scholar Henry Jenkins, Martin makes the relationship between class conflict and moral scares explicit, arguing that:

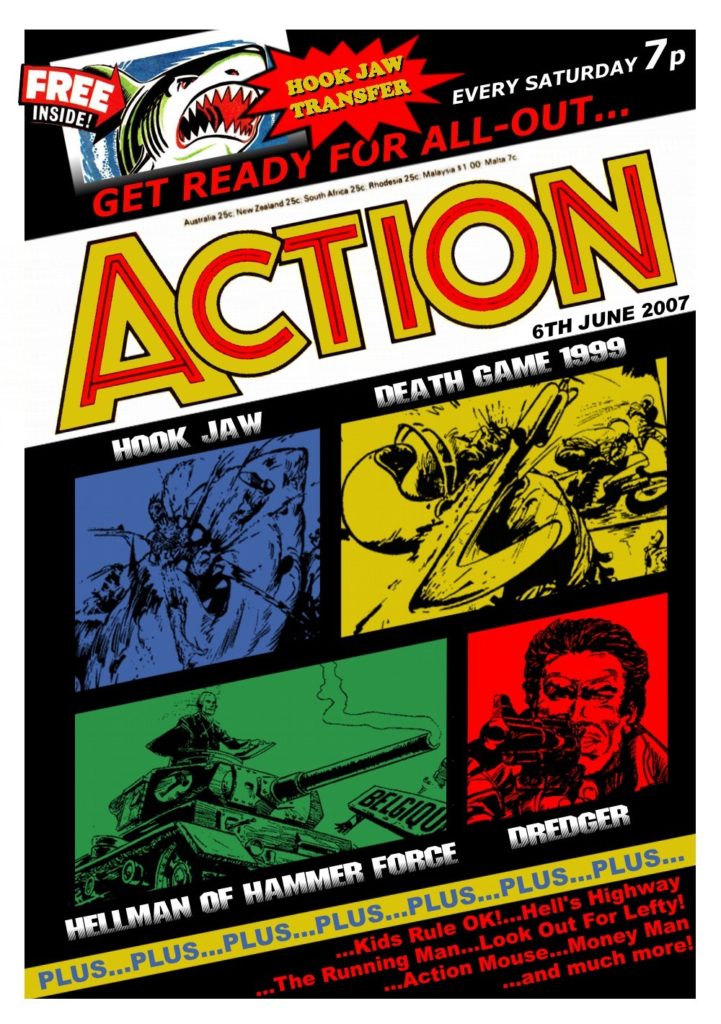

“The key thing about the comic’s various stories was their focus on confrontations with authority. Sometimes these were generically safe enough, as in the strip ‘Dredger & Breed’, which is set in the world of John le Carré and other spy narratives – but notice the evident hints at class as a dimension within the characters. Others were more overtly about contemporary, lived class experiences and conflicts – think ‘Probationer’, or ‘Kids Rule OK’ – both of which focus directly on young people’s conflicts with agents of the State”.

Inevitably, Martin came into conflict with other academic perspectives and other academics. Martin’s book, Comics: Ideology, Power and the Critics set him against prevailing perspectives that had gained purchase in Cultural Studies, particularly after the so-called “Events of May” in France, May, 1968.

Students at the Nanterre campus of the University of Paris had staged protests against restrictions on dormitory visits that prevented male and female students from sleeping with each other. This ignited demonstrations against the French State which, in response to police brutality towards the students, led to nationwide strikes involving eleven million workers. Fearing Civil War and Revolution, President Charles De Gaulle secretly fled to Germany.

“I was in the Maoist movement,” a participant in ‘The Events’ told me. “When you are young, it is a great pleasure to fight the police. I wanted to get the right-wing De Gaulle out!”

The hoped for revolution didn’t happen. In the wake of its failure, activists and academics saw that oppressive power was not monopolised by the State, but was dispersed across society.

For example, the Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser argued that there was a need to distinguish between the (Repressive) State Apparatus and multiple instances of an ‘Ideological State Apparatus’ operating in, for example, education and the law.

Roland Barthes provided a more fine grained and a more accessible analysis; reading images as linguistic signs that carried ideological connotations. “I am at the barber’s, and a copy of Paris-Match is offered to me”, He wrote. “On the cover, a young Negro in a French uniform is saluting, with his eyes uplifted, probably fixed on a fold of the tricolour. All this is the meaning of the picture. But, whether naively or not, I see very well what it signifies to me: that France is a great Empire, that all her sons, without any colour discrimination, faithfully serve under her flag, and that there is no better answer to the detractors of an alleged colonialism than the zeal shown by this Negro in serving his so-called oppressors.”

Barthes argued that the whole of France was steeped in an anonymous ideology “our press, our cinema, our theatre, our popular literature, our ceremonies, our Justice, our diplomacy, our conversations, our remarks on the weather, the crimes we try, the wedding we are moved by, the cooking we dream of, the clothes we wear, everything, in our everyday life, contributes to the representation that the bourgeoisie makes for itself and for us of the relationships between man and the world.”

Four of these French intellectuals were humorously depicted by cartoonist Maurice Henry (in La Quinzaine Litteraire, 1 July, 1967), as hanging out with anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss on a desert island. But Martin didn’t see cause to celebrate their works, writing, “I am very hostile to the whole of Althusser’s theories”. And he undoubtedly saw Barthes’ use of semiology, decoding ideology as if it were a structure of signs, as a bourgeois science, unable to account for the way meaning arises through historical struggle.

In an article for Radical Philosophy, Martin wrote, “on the face of it, radical understanding of the mass media has to count as one of the great success stories of the post-’60s political and academic culture”. But, as his qualification, ‘on the face of it’ indicates, Martin, again, had his reservations.

Barthes, whose articles had explored the ideological function of such staples of French Culture as steak and chips and the Citroen car and the different connotations of soap-powders and detergents, was to die in 1980 after being run over by a laundry van, but not before his method of critiquing culture had been adopted within British cultural and communication studies.

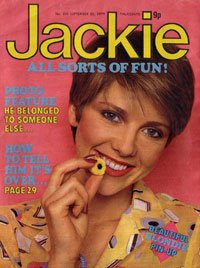

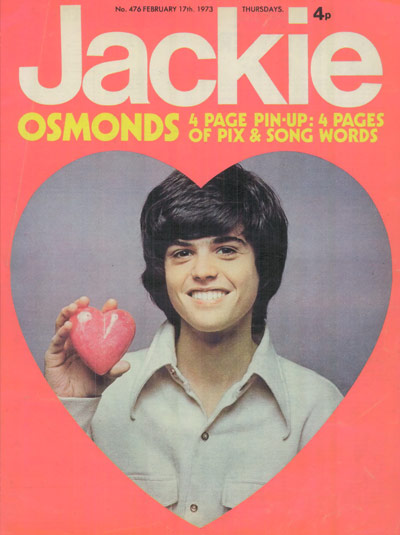

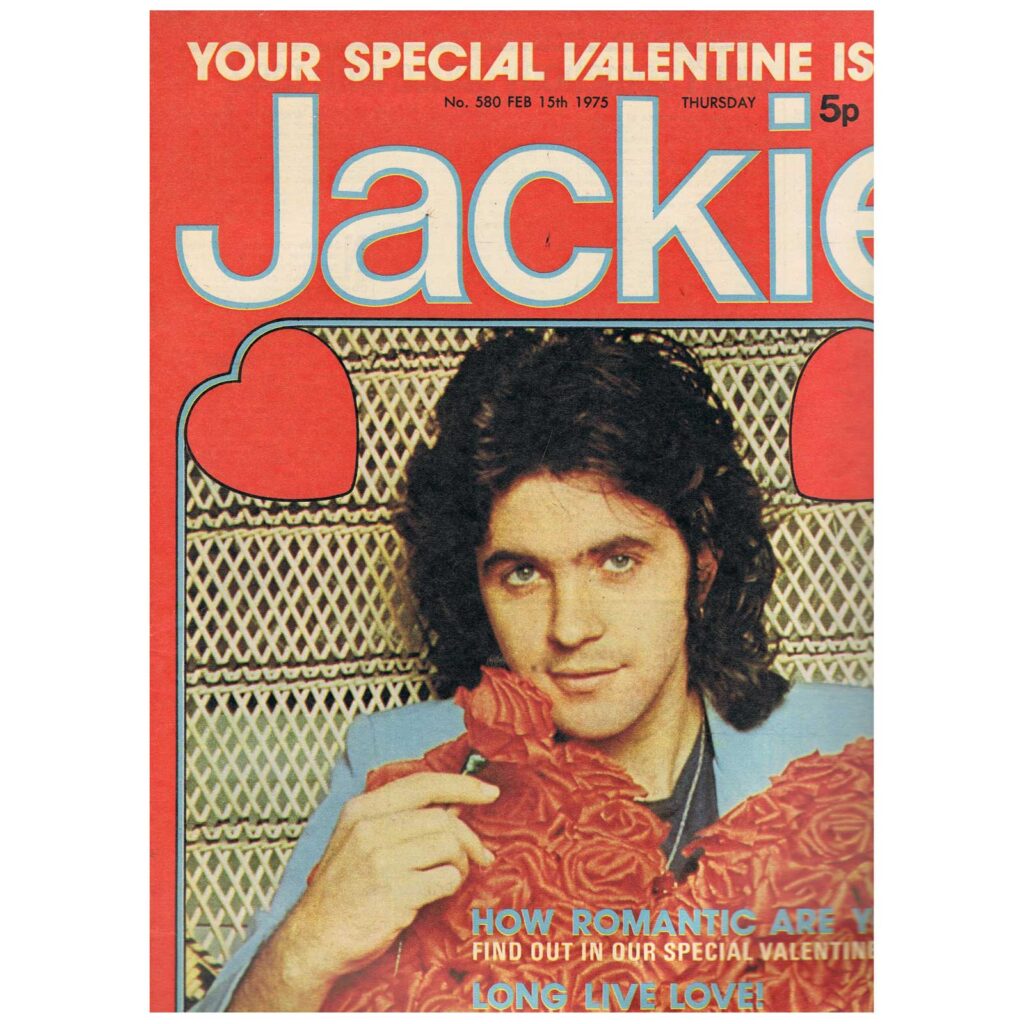

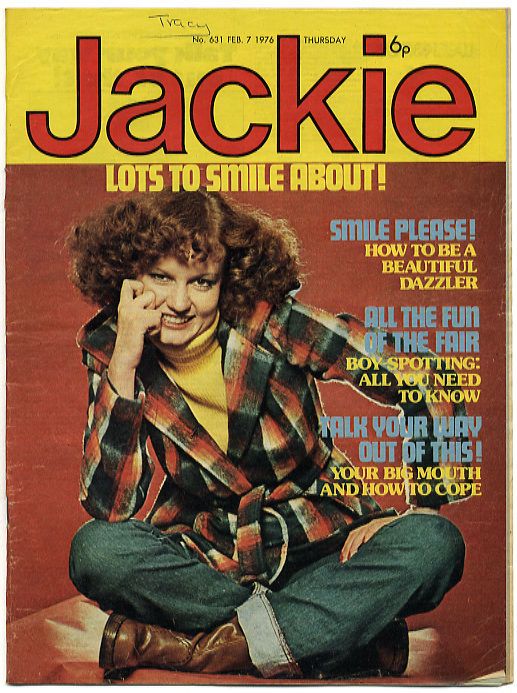

For example, Angela McRobbie used semiotics to analyse the girls’ magazine Jackie. Writing in Jackie: an ideology of adolescent femininity, McRobbie argued that Jackie made romance seem the natural preoccupation for young girls. In doing so, the magazine’s ideology defined girlhood in a way that divided women from each other in pursuit of a man and blocked wider life choices, including friendships and occupations.

Jackie’s function as a ‘myth’ was that this ideology seemed totally natural, the expression of essential femininity rather than an historically constructed identity, the product of patriarchy. McRobbie writes, “One of the most immediate and outstanding features of Jackie as it is displayed on bookstalls, newspaper stands and counters, up and down the country, is the ability to look ‘natural’ …this obscures the processes by which it is produced”.

Martin was having none of this, responding, “I always find myself wanting to ask silly questions when confronted with claims like this: like, would it be hiding or revealing its existence-as-a-commodity more if the price was covered up? I honestly do not know what is meant by this kind of claim that ‘appearing natural’ is a disguise for the process of production”.

Martin was also concerned that semiotics was a cover for just another theory of ‘media effect’; another example of words and pictures being granted power over those who engaged with them. This criticism extended to everyday and psychological concepts such as ‘identification’ and ‘stereotyping’. In The Lord of the Rings and ‘Identification’: a Critical Encounter, Martin argued that identification “has resisted testing because its status is essentially rhetorical. It belongs rather to the intellectual armoury of cultural critics who worry about moral harm.”

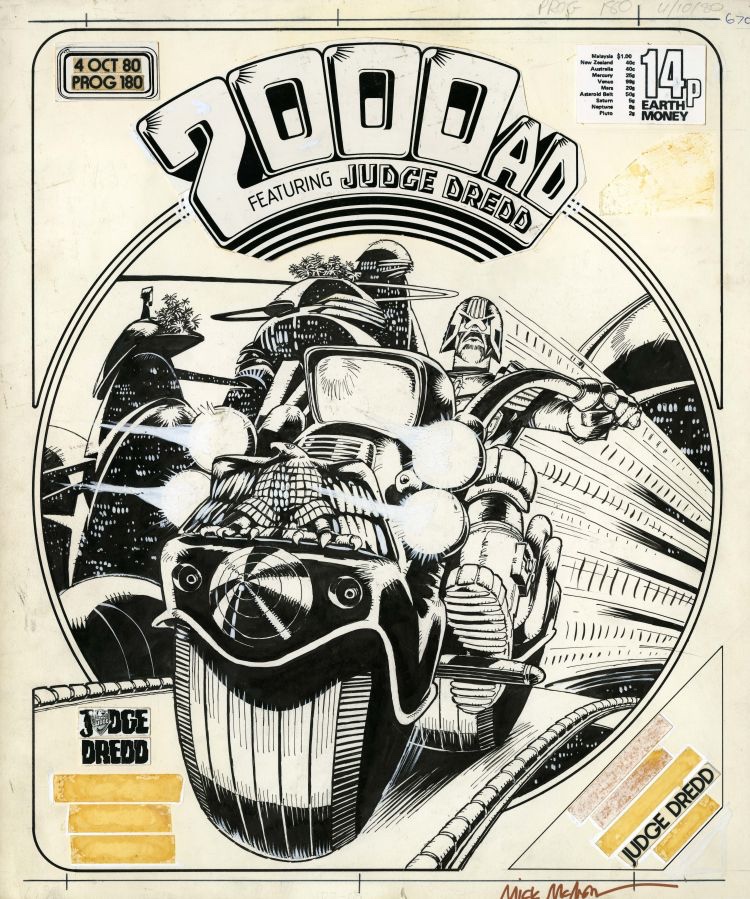

It was the wayward nature of media audiences that Martin seemed to enjoy most. Audiences’ interpretations of media products often defied expectations, particularly those of academic theorists. For example, British comics fans such as myself see 2000AD comic book character Judge Dredd as embodying and satirising an authoritarian police state not only in the future, but such tendencies in 1970s Britain, when the comic was launched. However, Martin liked to cite the example of one fan from his research, who was a self identified neo-nazi and felt Judge Dredd was something of a role model. What do you make of that? Martin would ask potential research assistants. For Martin, audience studies put the predictions of theory to the test.

It is clear that, in his reading of philosophy, Martin found a positive value in the work of the highly influential philosopher of science – Karl Popper (1902-1994). For Popper, it was the falsifiability of scientific theories that demarcated the difference between science and other forms of knowledge. And for Martin, falsification provided a basis of a truly scientific Marxism.

What makes this startling is that, as a Liberal philosopher, Popper had argued that Marxism was an enemy of liberal democracy and genuine scientific knowledge, stating, “Marx misled scores of intelligent people into believing that historical prophecy is the scientific way of approaching social problems.” Popper pointed out that “even if we observe today what appears to be a historical tendency or trend, we cannot know it will have the same appearance tomorrow.”

For Martin the outcome of the future was not inevitable, however the course of history remained shaped by class conflict. Comics played a part in this. But Martin also felt that all grand theories fell short when it came to researching the lived experience. In Comics, Ideology, Power and the Critics, he writes that to mention ‘grand theories’ calls up the ghosts of a whole tradition: Karl Marx, Max Weber, George Lukacs, Karl Mannheim, Lucien Goldmann, Antonio Gramsci, Louis Althusser…”In contrast, he writes, “My interest begins in the vast gap between these studies, and attempts to study ideology empirically.”

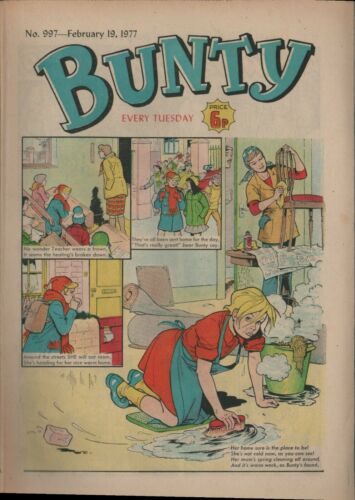

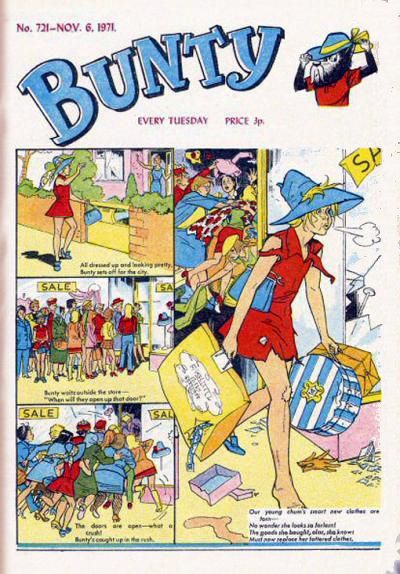

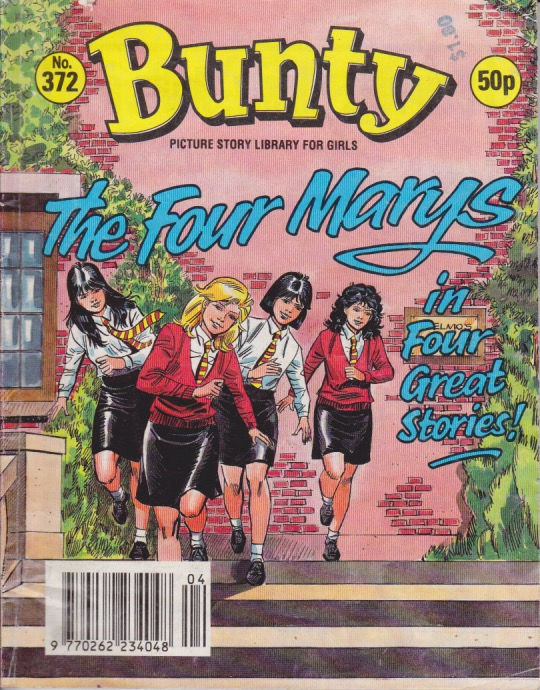

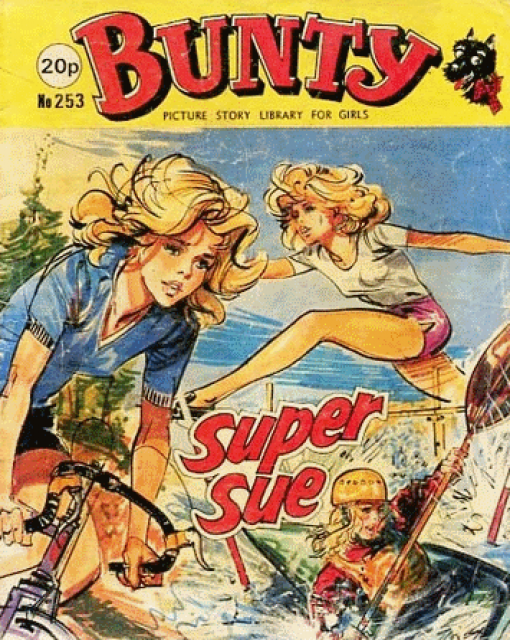

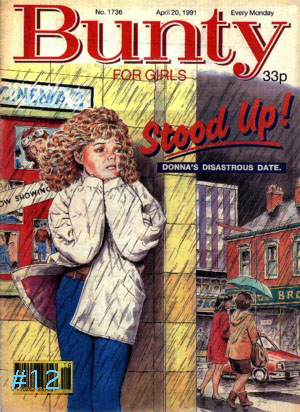

Interpreting comics readers in terms of their class identity was a priority for Martin. His critique of Valerie Walkerdine’s analysis of Bunty couldn’t be clearer in this respect.

Walkerdine, a Distinguished Research Professor of Cardiff University, has, with Chris Weedon, also of Cardiff University and others produced challenging and welcome critiques of psychological research. Walkerdine’s self-reflexive work has spanned academic research, art and photography, notably in her “Behind the Painted Smile” installation in The New Contemporaries exhibition. Walkerdine analysed Bunty through the lens of psychoanalysis, arguing that its stories were fantasies that shaped the psychic structure of young girls’ desires.

In contrast, Martin put Walkerdine’s theory on its feet, writing “I can only offer the bones of an alternative… It involves reversing Walkerdine’s picture of class and gender”. Martin characterises Bunty’s stories as “unresolved dramas of the class-experience of working girls”. They do this by “showing the deeply hopeless lives of young girls. However hard they take the expected responsibilities, they have no escape”. But in doing so, the stories expressed rather than create such conflicts in the minds of their readers.

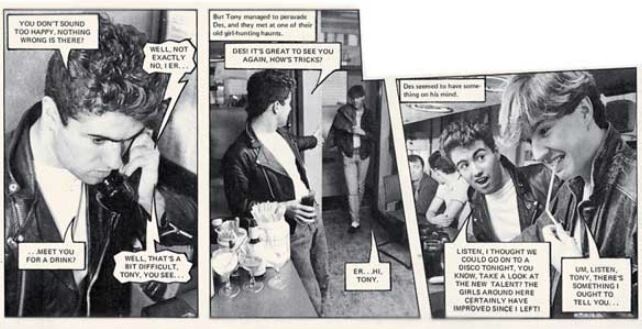

Martin clearly saw the potential of, for instance, the comic Action to provide a basis for challenging authority. He says,”Action stood at the edge of a very radical politics,” one that challenged notions of childhood and the relationship between children and adults.

There has been a tendency on the academic Left to imagine resistance and revolution as a ‘boy’s own adventure’. Martin carefully notes that Action had girls and boys as readers. Although, when he says that kids “ran the streets of Brixton on the day its withdrawal became known, shouting ‘They’ve taken our comic!’ I do wonder how many of us think those kids were girls?

I certainly think Martin saw signs of a more authentically working class revolt in those kids’ behaviour, running down the streets of Brixton, than in any student at the barricades in France, May, 1968. It was as if breaking the contract between the comic and its readers was also a breach of the contract between kids and a wider society of adults.

Martin’s research was concerned with the place of the media in relations of class struggle and not as the cause of effects, anti-social or otherwise. Knowing that his time was running out, Martin never-the-less wanted to explore what “a Marxist theory of cultural reception might actually look like”

In the end, Martin’s legacy lies in his practice of documenting a number of specific accounts of particular struggles involving comics, films and television. In this, Martin’s work is not totalising, but exemplary.

Tim Robins, M.Sc, Birmingham Centre for Cultural Studies

Martin Barker, 20th April 1946 – 8th September 2022

Further Reading

• The New Racism (1981)

• A Haunt of Fear: The Strange History of the British Horror Comics Campaign (1984)

• Comics: Ideology, Power and the Critics (Cultural Politics) (1989)

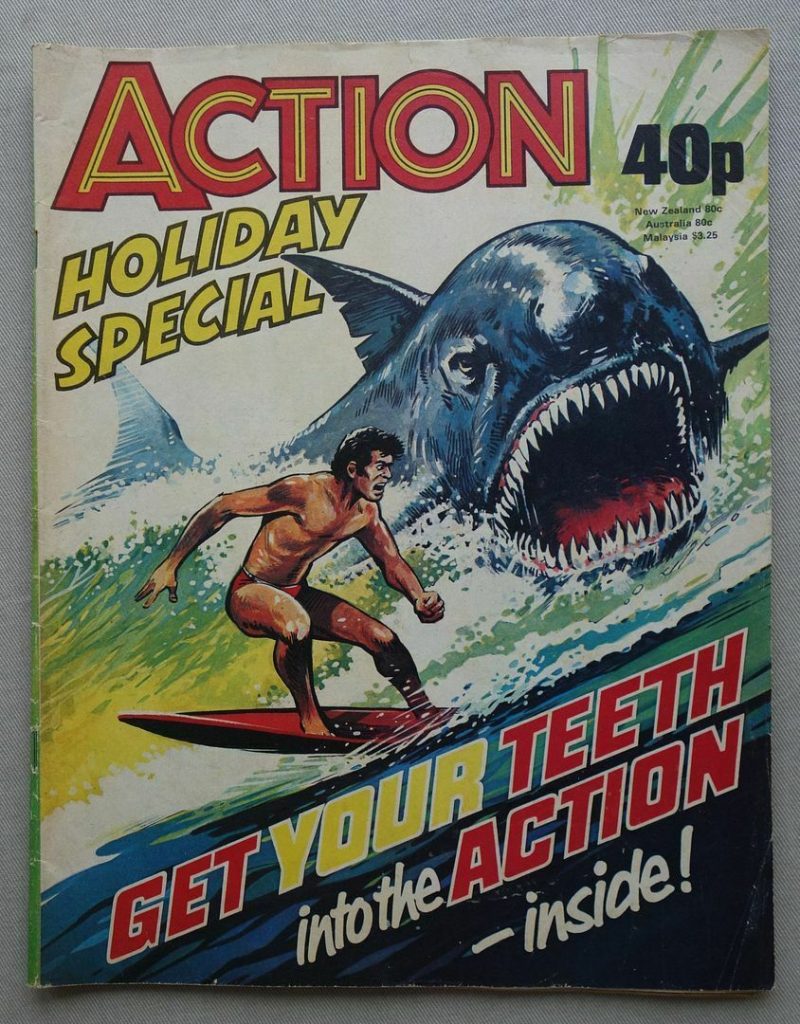

• Action: The Story of a Violent Comic (1990)

The story of the controversial boy’s comic, Action, created by Pat Mills, loved by its fans, censored, and then withdrawn under a year later

• A Haunt of Fears: The Strange History of the British Horror Comics Campaign (1992)

An exploration of the British campaign against horror comics between 1949 and 1955 that led to the passage of the Children and Young Persons Act of 1955

• Knowing Audiences: Judge Dredd – Its Friends, Fans and Foes (1998)

• The Video Nasties by Martin Barker (1999)

• Ill Effects: The Media Violence Debate (2001)

• Reading Into Cultural Studies by Martin Barker, Anne Beezer (2003)

• The Lord of the Rings and ‘Identification’: a Critical Encounter (2005)

Watching The Lord of The Rings: Tolkien’s World Audiences, co-authored with Ernest Mathijs (2008)

With thanks to Dr Daniel Haines Cohen (Critical and Cultural Theory, Cardiff) of Machine Records, NZ; actor and recording artist Laurence R. Harvey, (MA, Art and Performance Theory, Wimbledon, and Gennine Nethercott, singer, for their invaluable feedback and encouragement on an early draft of this piece.

A freelance journalist and Doctor Who fanzine editor since 1978, Tim Robins has written on comics, films, books and TV programmes for a wide range of publications including Starburst, Interzone, Primetime and TV Guide.

His brief flirtation with comics includes ghost inking a 2000AD strip and co-writing a Doctor Who strip with Mike Collins. Since 1990 he worked at the University of Glamorgan where he was a Senior Lecturer in Cultural and Media Studies and the social sciences. Academically, he has published on the animation industry in Wales and approaches to social memory. He claims to be a card carrying member of the Politically Correct, a secret cadre bent on ruling the entire world and all human thought.

Categories: British Comics, British Comics - Books, Comics, Comics Studies, downthetubes Comics News, downthetubes News, Features, Obituaries

Incredibly sad news. Phenomenal writer. Rest in peace, Martin.