Review by Tim Robins

WARNING: SPOILERS AHEAD!

While vacationing at a remote cabin, a young girl and her parents are taken hostage by four armed strangers who demand that the family make an unthinkable choice to avert the apocalypse. With limited access to the outside world, the family must decide what they believe before all is lost…

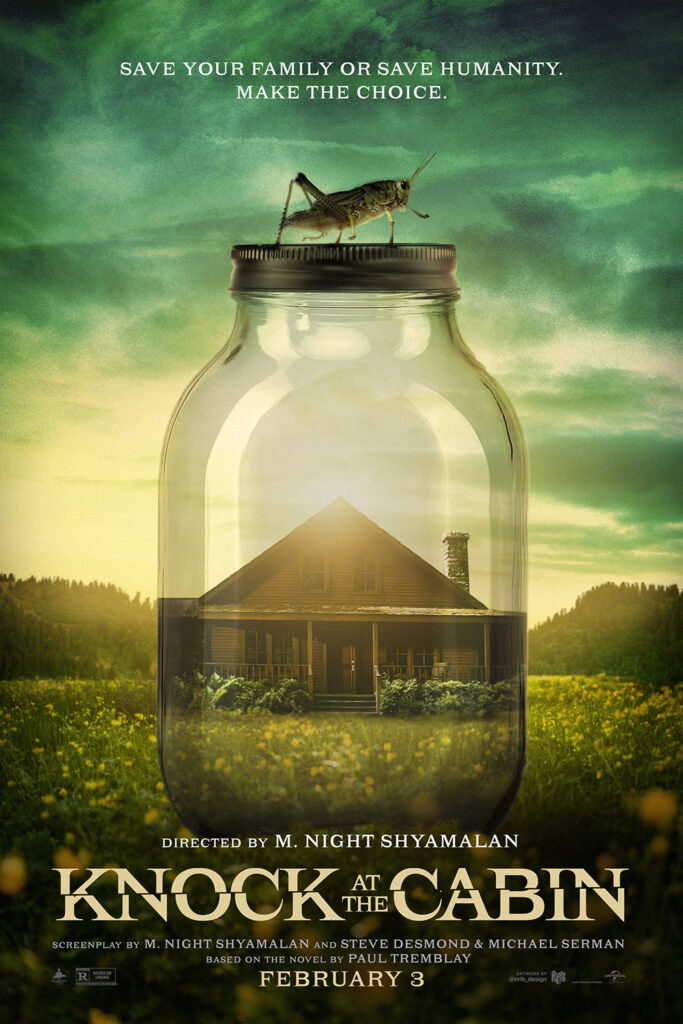

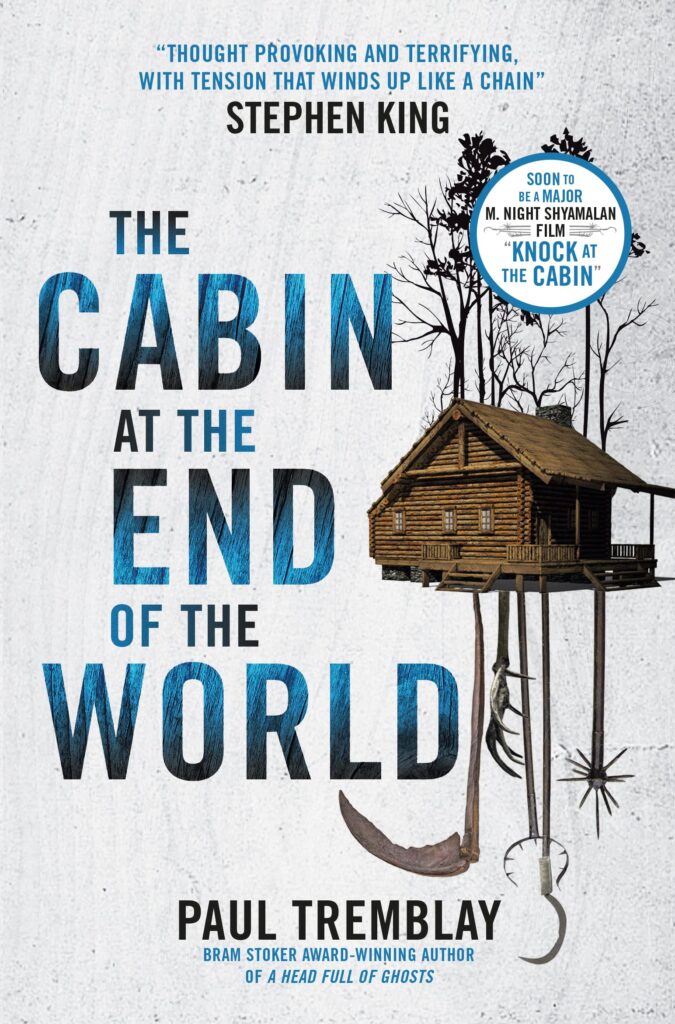

Watching Knock at the Cabin feels like being terrorised by director M Night Shyamalan for the best part of two hours. The film, based on the Stoker Award-winning novel, The Cabin at the End of the World by Paul Tremblay, is viscerally tense from the start, when a young girl is seen collecting grasshoppers in a large, glass jar. As we voyeuristically watch characters on screen, the film suggests that we too are being inspected by a higher power.

The story is an extraordinarily potent mix of religiosity, violence, suicide, and child endangerment, all of which may explain why the film has been rated ‘R’ (no-one under 17 admitted unless accompanied by an adult) in the United States and 15 in the UK (no one under 15 can see the film in the cinema). The tension begins right from the get go, with Dave Bautista walking up to talk to young Kristen Cui, in a scene echoing that scene in Frankenstein where the Monster watches a little girl throwing flowers in the water, before doing the same to her.

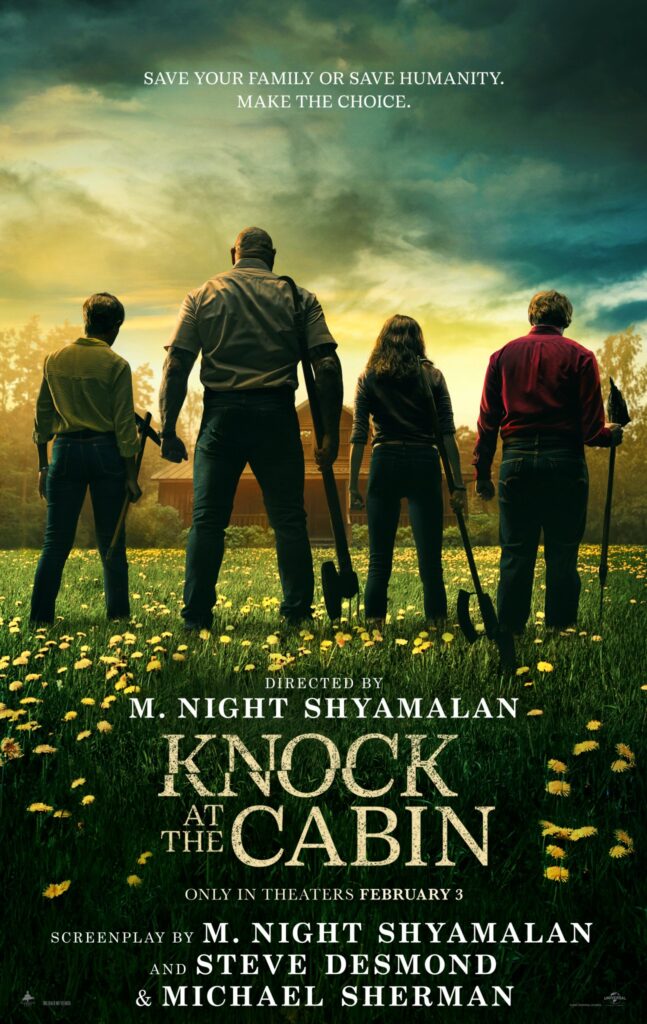

The plot, as you may know by now, involves parents Eric (Jonathan Groff) and Andrew (Ben Aldridge) and their adopted eight-year-old child, Wen, (Kristen Cui) being confronted by four strangers who break into their holiday home and announce that the couple kills one member of their family, in order to stop an imminent apocalypse ordained by God. The film never entertains that Wen has any say in the matter, or that she might be chosen, instead; the child is confronted by a number of gory murders, although, for us, much of the gore is implied.

The performances are compelling. As film critic Chris Stuckmann has pointed out, you feel that everyone in the film is scared, including the intruders, who don’t want to die and are desperate to make the couple believe that their prophecy is real. Dave Bautista, as Leonard, tries to ensure calm and remains softly spoken throughout but this gentleness increases the horror.

Rupert Grint plays one of the messengers. His name is Redmond, he has red hair, and he is an angry man – geddit? Nikki Amuka-Bird and Abby Quinn play the remaining visitors, Sabrina and Adriane. All are absolutely compelling, as they plead with the family to make the choice for the sake of their own and humanity’s lives. The young Cui is completely convincing as Wen, displaying the intelligence, resolve and courage that many children have.

Shyamalan is on top form, bringing together shot and situation previously seen in Signs, the The Village and Old. Like those movies, Knock at the Cabin in deals with isolated individuals under threat and, like The Lady in the Water, imbues the everyday with a magical or spiritual significance. Apart from a few flashbacks, the events are located almost entirely in the cabin which led me to see Knock at the Cabin as the director’s take on Tarrantino’s Hateful Eight.

Shyamalan’s love of Alfred Hitchcock is obvious. He manages to wring suspense even from such clichéd set-ups as ‘has the person in the bathroom escaped by the window or are they hiding behind the shower curtain?’ And, like Hitchcock, Shyamalan manages to contrive an appearance in his own film; this time, in an amusingly silly TV advert for a chicken fryer.

The television is an eighth member of the cast, fulfilling its cultural form by reporting on global disasters which may or may not be happening in the outside world. This ambiguity is given particular force by today’s “fake news”, “post truth” politics. Are the imputed prophetic events really happening, and even if they are, did the visitors really share prophetic visions of them? We are put in the position of the two parents, of not entirely being sure – did a concussed Eric really see a vision of God in the light pouring through a window? His husband is not at all sure, and he is aware that his partner is of Christian faith and may be prone to seeing signs passing as wonders.

Knock at the Cabin has the feel of a movie with a message or, at the very least, social commentary much like those post-apocalyptic movies that leave a White man, a Black man and a White woman as the only survivors of an apocalypse. I think the film’s choice of a gay couple adds a lot to the situation. LGBTQ people must put up with threats of violence and actual violence in their everyday lives. Andrew’s experience of being “bottled” by an angry customer in a bar feels authentic. His recurring trauma, and his deep-seated suspicion that the man who assaulted him is now in the cabin, have the power of authenticity.

The cabin setting does have significance for imaginings of American society akin to The Island in those so-called “Robinsonades, in which castaways seek to recreate civilization. The isolation of a cabin in a wood mirrors the isolationist strand of American politics including social isolation which breeds a deep suspicion of socialism all of which must surely rest on a deep-seated isolation of the heart that must exist where extreme individualism prevails.

The religious themes don’t bear much scrutiny. The film leads you to see the four intruders as the four horsemen of the apocalypse, but, actually, they are their antithesis. And we aren’t watching the actual details of ‘End Times’ prophecy, because a person of faith such as Eric might well welcome Judgement Day.

The film’s climax certainly runs against the Bible story of God’s test of Abraham – first demanding him to sacrifice his son Isaac but then, at the last moment staying the Father’s hand with the words, “Lay not thine hand upon the lad, neither do thou any thing unto him: for now I know that thou fearest God, seeing thou hast not withheld thy son, thine only son from me”. There’s no such restraint in Knock at the Cabin, although the air of religiosity, in addition to the novel it’s based on, recalls William P. Young’s 2007 novel The Shack, in which a bereaved father is invited to meet God in a cabin in the woods.

I’m not surprised that some critics have accused Knock at the Cabin of being homophobic, or violently punishing gay men on behalf of Evangelicals. I don’t think it does, but I was surprised that we didn’t see the couple sharing a last kiss good-bye. That possibility is just treated as yet another moment of suspense. Shyamalan really does treat the characters, and, by extension, the audience, as little more than insects contained in a jar.

And, as the post-end-credits clip suggests: ask not for whom there is a knock at the cabin door, the knock is for you…

Tim Robins

• Knock at the Cabin is in cinemas across the UK now | Web: knockatthecabin.com

• Follow M. Night Shyamalan on Twitter

• M Night Shyamalan is online at mnsfoundation.org

The M. Night Shyamalan Foundation supports the grassroots efforts of emerging leaders as they work to eliminate the barriers created by poverty and social injustice in their communities

• Buy The Cabin at the End of the World by Paul Tremblay | AmazonUK Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org | ISBN: 978-1803364148

• Follow Paul G. Tremblay on Twitter

A freelance journalist and Doctor Who fanzine editor since 1978, Tim Robins has written on comics, films, books and TV programmes for a wide range of publications including Starburst, Interzone, Primetime and TV Guide.

His brief flirtation with comics includes ghost inking a 2000AD strip and co-writing a Doctor Who strip with Mike Collins. Since 1990 he worked at the University of Glamorgan where he was a Senior Lecturer in Cultural and Media Studies and the social sciences. Academically, he has published on the animation industry in Wales and approaches to social memory. He claims to be a card carrying member of the Politically Correct, a secret cadre bent on ruling the entire world and all human thought.

Categories: Features, Film, Other Worlds, Reviews

In Review: Twisters

In Review: Twisters  In Review: Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes

In Review: Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes  In Review: Rebel Moon Part 2 – The Scargiver

In Review: Rebel Moon Part 2 – The Scargiver  In Review: Civil War

In Review: Civil War