Leonard Matthews, General Managing Editor of Fleetway and the Eagle Group of Comics, was a “Creative Visionary”… but, that, Roger Perry argues in his extensive biography of the man which continues here on downthetubes, is only due to him having utilised the ideas of others.

Here, Roger explores the beginnings to the destruction of the Eagle…

How a Marks & Spencer Floor Detective Became Managing Editor of Eagle

“D-Day”… “Destruction Day”

Tuesday, 5th September 1961

(If you haven’t already read Part 4 of this ongoing feature, it’s here)

The first any of us had known anything about all this was when a message came around saying that everyone must congregate in “The Big Art Room” at 3 o’clock precisely – no-one, but no-one, would be excused. I have now begun to say “us” and “we” rather than:”they” and “them” as just one week before this auspicious day – this having been Monday 29th August, 1961 – I too had become a member of this team and had, therefore, personally become involved in all that was going on at Juvenile Publications.

Standing there in their smart cavalry-twill great-coats (despite it being early September and still relatively warm), hats (remaining squarely upon heads) and tinted horn-rimmed glasses (giving them a certain amount of anonymity), there had been a distinct resemblance between the three “Mafioso-hoods” standing there before us and those other undesirables one hears about that hale only from the mountainous nether regions of Southern Sicily.

With George Allen to one side and David Roberts on the other, Leonard James Matthews stood high (in built-up shoes) and began to lay down his law. In reeling off a list of changes that will be supplemented forthwith (or expect the consequences), he spoke of exchanging “expensive” artwork (that had been the hallmark of Eagle’s success) with material that had at some time been used elsewhere and was now lying idle in some godforsaken damp vault doing little more than gathering dust. In the course of conversation, he raised the subject of Frank Hampson’s wasteful £60 a week stipend and he also spoke of competitions – of which from now on, there would be no more… he didn’t believe in them!

Having gone on for seven to ten minutes – Matthews’ outrageous demands visibly creating anarchy and mayhem – in the midst of the bedlam, one Art Editor, having voiced his objection and asking Matthews as to what authority he had to stipulate these changes, was first asked to identify himself… before being bluntly told that he should “clear out his desk and leave by Friday”

(55 years on, this same gentleman likes to give more anaesthetized version to his rather rapid departure).

I noted with interest one or two others – one of them being Keith Motts (who up to now had been in charge of competitions) – was also keen to voice an objection . . . that was until he saw what had happened to Charlie Pocklington.

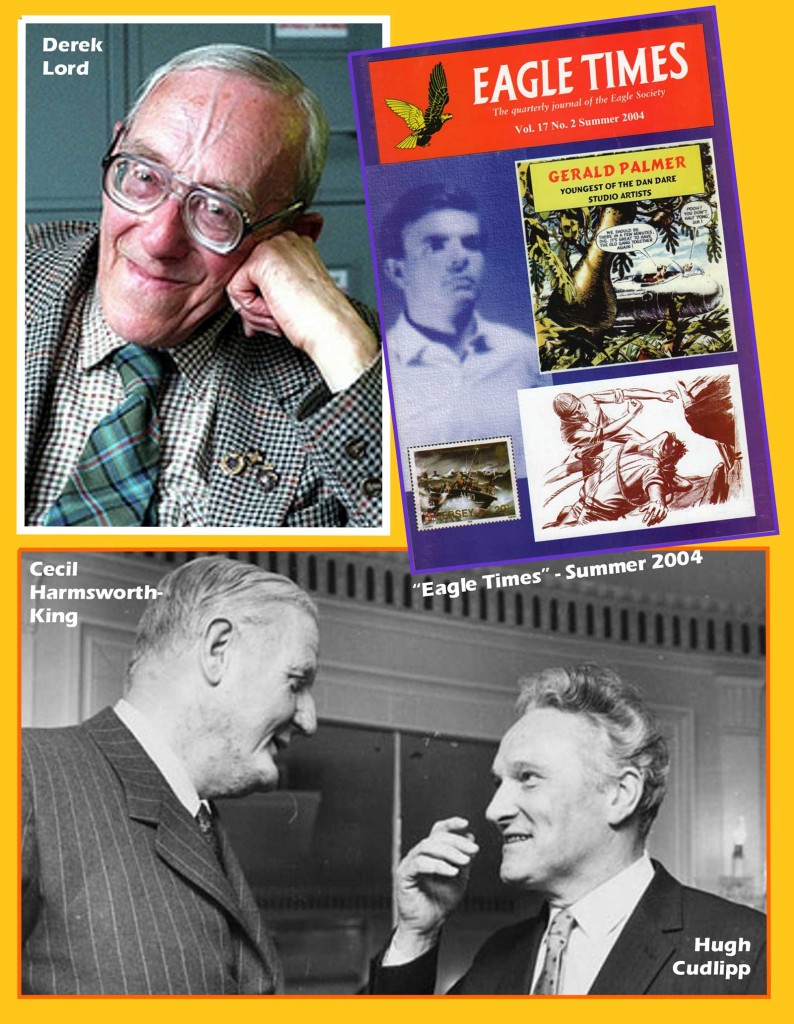

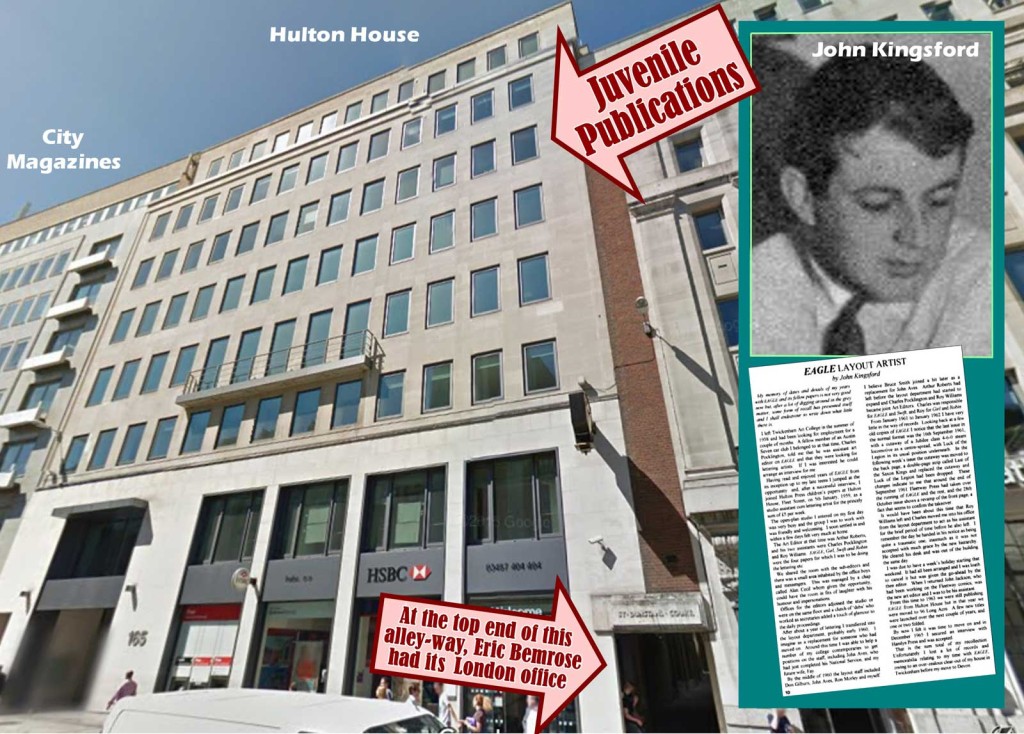

Yes, 55 years on, but with ex-colleagues dying left, right and centre or are now in such a vegetative state that confirmation of these events is hard to come by, I was particularly gratified to discover that John Kingsford (one of the four designers on the comics) had independently written an account of great similarity to all that I say had transpired on that fateful day. Kingsford, who’d been employed by the Eagle Group since 5th January, 1959 had, just one day earlier, been promoted to the position of Assistant Art Editor so that he might replace Roy Williams who had left Juvenile Publications on the previous Friday. The following piece was written by him for Eagle Times, the magazine of the Eagle Society:

“It would have been about this time that Roy Williams left and Charles moved me into his office from the layout department to act as his assistant for the brief period of time before he also left. I remember the day he handed in his notice as being quite a traumatic one, inasmuch as it was not accepted with much grace by the new hierarchy. He cleared his desk and was out of the building that same day.”

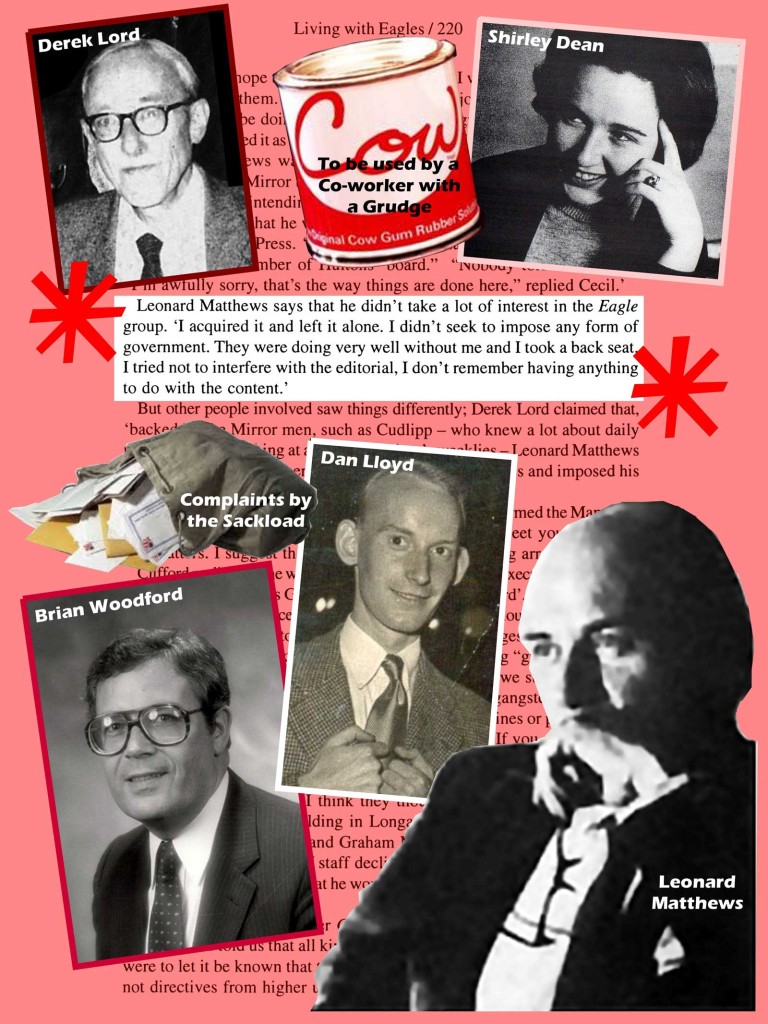

John’s account is not entirely accurate… but is close enough to endorse the point that I am wishing to make. As for the remaining employees, the indignation surging throughout that room had been such that a large number of senior staff – starting off with Eagle editor Derek Lord – bawled out in no uncertain terms their intention to resign (which was quickly followed by three or four others, including Girl editor Pat Jackson and Robin editor Rosemary Garland. Of course, in their own individual cases, it had taken them rather longer to “clear their desks and leave by Friday” – four lots of Fridays in fact, which was the obligatory notice period in those days… senior management or not).

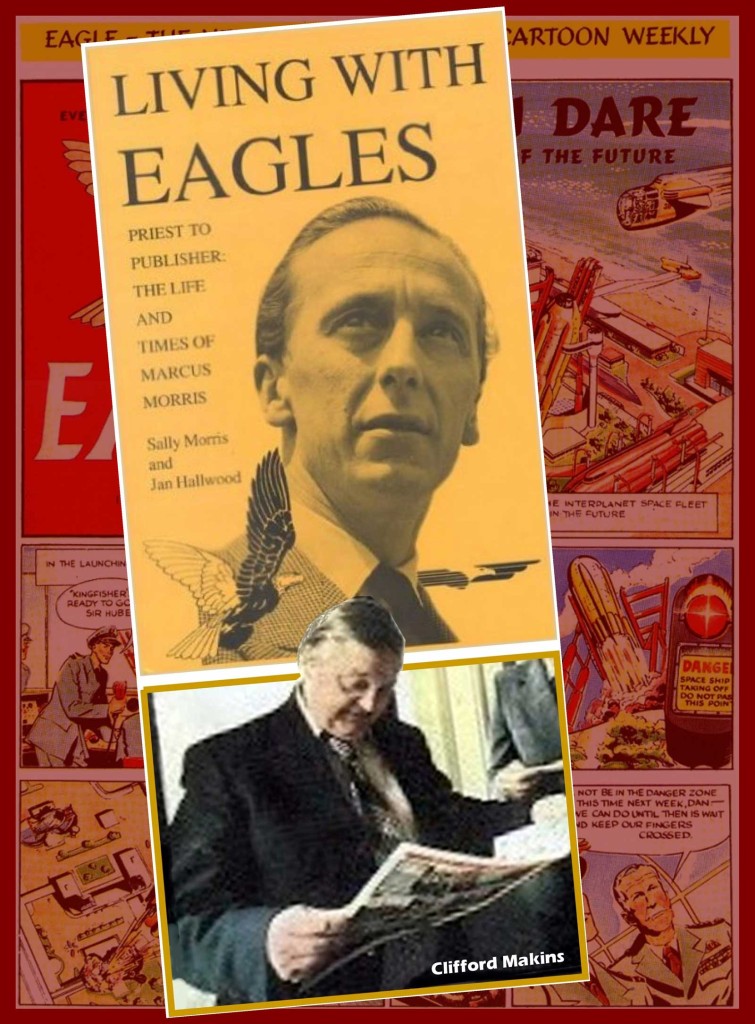

One person who hadn’t given any “notice period” whatsoever but had just got up and walked out was the unfortunate Managing Editor – the “un-co-operative puppet” – Clifford Makins. By 5.30, when everyone else was packing up their belongings in readiness for heading off home, Makins had already left and gone. He’d slipped out unobtrusively without saying a single, solitary “goodbye” to anyone. Not that there had been any real reason for him to have done so – at least, not to me, for in the seven days I had been there, not once did I ever see (or meet) the man.

Quoting from Living with Eagles, the text (on page 220) reads:

Clifford described it as: “a time of real hell. I was left with a bloody shambles.”

Again from Living with Eagles, but this time from page 222:

Marcus [Morris] wrote to Clifford twenty years later: “You made a great contribution to the children’s papers. I’m sorry you had to fight such battles after I left with the appalling people who moved in”.

I learnt some time later that Matthews had been quite stunned by this sudden “mass-walk-out”. It had been totally unexpected and something that he had not foreseen in any way. However, it didn’t prevent him from continuing to hack away at Eagle and its uniqueness.

Again from the Living with Eagles (page 222):

As Dan Lloyd, the new Chief Sub had said: “Fleetway rooted out most of the stuff people bought Eagle for and put in a lot of the rubbish they had in their morgue. Some of that was originally black and white, and had to be coloured up to be introduced as a marvellous new feature. Eagle lost all the appeal it originally had and that was reflected in plummeting sales.”

On the following Monday – 11th September, 1961 – Val Holding arrived to sit in Makins’ empty chair. Matthews had given him a one-year contract to come in daily; to sit in that room; and above all, do nothing and touch nothing. In that one year, I saw Holding precisely once – not in any editorial capacity I might add, but more so that we had passed by in the corridor while going towards the lift. He hadn’t a clue as to who I was… not that that had made any difference.

The loss of key staff had been one thing; the changes that Matthews had imposed upon Eagle’s art content had been quite another. When the downgraded art reached the eyes of dedicated readers, they were so utterly appalled that within weeks, there had been a loss of 150,000 sales. The circulation had plummeted from 500,000 copies weekly and down to 350,000.

Letters of complaint poured in by the sack-load… and every one had remained unopened, unanswered and unloved.

“I have no problem believing that Matthews screwed up Eagle”, says Brian Woodford, whose credits during his career include being Chief Sub-editor for Boys’ World and WHAM!. “He certainly was a man who would brook no opposition once he got his mind and sights set on something.

“There is no telling what his thinking was in regard to Eagle when he took over… his killing of it might even have been intentional.”

But what was so particularly galling was the quote that again is taken from Living with Eagles (page 220):

Leonard Matthews says that he didn’t take a lot of interest in the Eagle group.

“I acquired it and left it alone. I didn’t seek to impose any form of government. They were doing very well without me and I took a back seat. I tried not to interfere with the editorial. I don’t remember having anything to do with the art content.”

Repeating what I said at the beginning of Part Four: it would appear that his recollections of that tempestuous period don’t quite fall in line with those recollections by others who had experienced those same events.

Matthews certainly had some fairly bizarre ideas. Should you wish to type “Leonard Matthews, Fleetway” into an internet search, you should find his Wikipedia entry. Towards the very end you will see that it states:

“No male employee (or female supposedly) was allowed to have a beard or they’d be sacked.”

Supposition? (After all, Wikipedia has been known to make the occasional gaffe, given its user-submitted nature, both deliberate and accidental). Well, not in this case. Fleetway designer Trevor Christmas was indeed given the sack for attempting to grow a beard. (Although there might have been rather more to it than Trevor wished to divulge to me. I add this proviso in the light that when he had been, accidentally or intentionally, locked out on the fire-escape, in order to gain entry into Fleetway House, he had physically punched a hole in the reinforcing glass thus cutting his hand quite badly in the process).

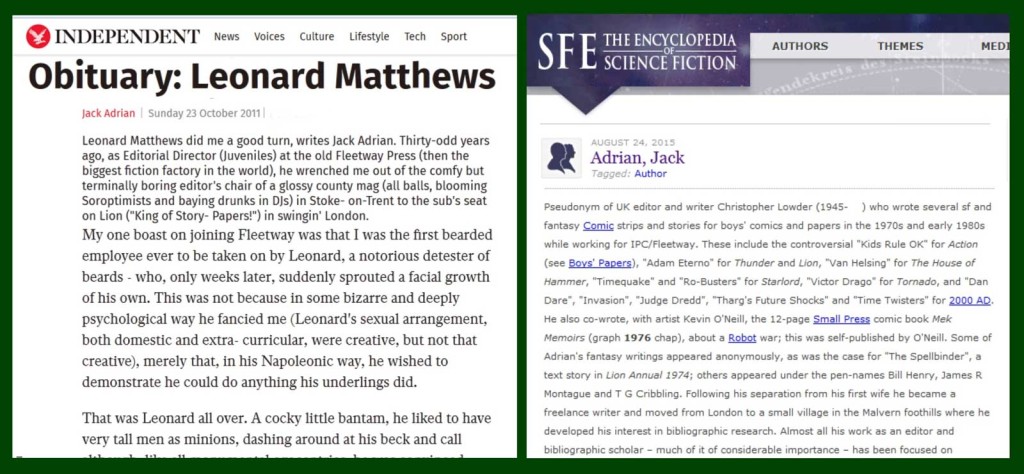

To back up what I (and Wikipedia) have to say in regard to the “no-beards rule”, I now interject a piece I discovered just recently, which appeared in the Independent newspaper dated Sunday, 23rd October 2011. It comes from an article by Jack Adrian, one of many pseudonyms used by editor and writer Christopher Lowder, supplementing the paper’s earlier obituary of Leonard Matthews by George Beal:

My one boast on joining Fleetway was that I was the first bearded employee ever to be taken on by Leonard, a notorious detester of beards – who, only weeks later, suddenly sprouted a facial growth of his own. This was not because in some bizarre and deeply psychological way he fancied me (Leonard’s sexual arrangement, both domestic and extra-curricular, were creative, but not that creative), merely that, in his Napoleonic way, he wished to demonstrate he could do anything his underlings did.

Jack Adrian wrote several SF and fantasy strips and stories for boys’ comics and papers in the 1970s and early 1980s while working for IPC/Fleetway. These include Action‘s controversial “Kids Rule OK” as well as “Adam Eterno” and many others.

Another headache (or distraction for Matthews) had taken place one Friday night after everyone else had left to go home for the weekend. Some resentful soul (who was never ever identified) had run a trail of pungent Cow Gum rubber adhesive between the lift-shaft – where he had made his escape – and over to the store of artwork. As the lift doors closed, he’d “lit-the-blue-touch-paper” and then pressed the lift button for the ground floor. I believe the dastardly plot to destroy the art on site was thwarted mainly due to the overhead sprinkler system kicking in and doing the job it was originally designated for.

To replace those members of staff who had resigned, substitutes more obliging toward Leonard Matthews were shipped over en masse from Fleetway. These were Val Holding (Managing Editor); Andy Vincent (who became Eagle’s new editor); Barry Cork, taking on the role of editor of Robin (and as a temporary measure, had also been editor of Girl until such time when Margaret Pride could be released from her editorial duties on Reveille and Weekend Reveille); and John Jackson (as overall Art Editor for the four papers).

When Jackson came on board, John Kingsford automatically became his assistant (as he would have been had Charles Pocklington not left.

I knew so little as to who these “substitutes” were… or what wonderful things they might or might not have supposedly done in the past. Reflecting back fifty-plus-something years, I now have to ask myself, were these replacements brought in as “Knights in Shining Armour” in order to help save the day… or were they perhaps just little more than “cast-outs” who by that time had outlived their usefulness at Fleetway anyway?”

Harsh words I know, but it must be crystal clear to you all that Matthews really hadn’t cared one way or the other as to whether the Eagle Group had “survived or had sunk into total oblivion”. All that really interested him was placing himself in a good light with both the Mirror hierarchy and the Odhams / Longacre / Hulton board over his achievement at having cut back on the high cost of Eagle et al’s overheads. Perhaps behind it all, he was still seething over his failure to haul in his most prized catch of all time… the erratic Frank Hampson.

To make quite sure that everyone had been following his directives to the letter, following the arrival of the latest pasted-up Eagle dummy produced by Liverpool-based printer Eric Bemrose, Andy Vincent – much like the smarmy school prefect who blatantly brown-noses his house-master, each subsequent week – had religiously escorted it personally over to Fleetway House for the sole purpose of obtaining approval for the content from his beloved lord and master – Leonard James Matthews.

I shall now bring forth a couple of “eccentricities” that revolve around Matthews’ unpredictable befriending and hiring of virtually complete strangers.

The man who had taken over Clifford Makins’ position as Managing Editor was Val Holding. It had been pretty common knowledge at the time how Matthews had originally come into contact with him – not within the world of publishing or at some “upper-crust” party held by the Writers’ Guild – but, of all places in a Marks & Spencer high street retail outlet. Holding had had a job there as “a floor-walker” – an in-house store detective – and being tall (something that Matthews had always admired in a man), they had obviously entered into a conversation whereby the result had been that Matthews had offered Holding a job at Fleetway before giving him the job of Managing Editor of Juvenile Publications.

But this odd quirk of insanity hadn’t been the only example of Matthews’ manic whims. We now come to Eric Meredith.

During the spring of 1961, Eric Meredith had had circumstance to visit Leonard Matthews’ home in Esher. He had gone there on a number of occasions as he had been commissioned by Matthews to create some “wrought-iron garden furniture”. Oddly enough, Meredith had been quite a short man – so short that co-designer Ron Morley had quickly nick-named him “The Boy From Robin”, a title inspired by Meredith’s appointment as “The Man From Eagle”. During his short spell with us, he probably wrote no more than two or three articles – at least, one has to suppose that it had been he who had written them.

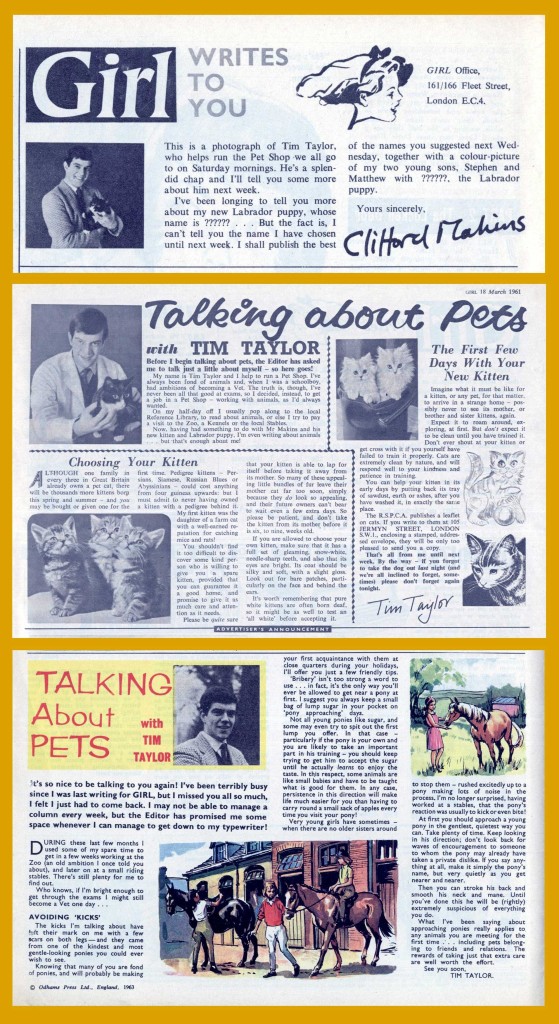

And having spoken of Ron Morley has reminded me that he too had become immortalised, but in his case, it was within the pages of Girl magazine. Starting in March of 1961, Ron had taken on the role of “Tim Taylor”. According to Clifford Makins’ editorial page, Tim Taylor was a vet who had worked at the local pet store. Hhhmmm, what is it that they say? . . . Never believe anything you read in the newspapers?

In Part Six… Now, what have I put into Part Six? Oh, yes, I speak on whether the treatment of Frank Hampson had been fair or not, and at the same time offer a blow-by-blow account of what happened when editors Alan Fennell and Dennis Hooper of Century 21 Publishing also tried to offer him regular work…

Roger Perry

The Philippines

With acknowledgements to David Slinn and to Darren Evens of Eagle Times for producing certain scans used in this article.

[divider]

More Eagle Daze…

Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part One

Roger explores the beginnings of the destruction of the Eagle…

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part Two

The comic magazine Top Spot, published in 1958, was Matthews’ brainchild – but it was the male counterpart of an already existing magazine and it was a title that faced plenty of problems as it ran its course before merging with Film Fun after just 58 issues…

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part Three

Roger outlines how Matthews jealousy almost destroyed the Eagle…

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part Four

Roger reveals a possible mole working on the Eagle and trouble behind the scenes on Girl…

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part Five

How a Marks & Spencer Floor Detective Became Managing Editor of Eagle…

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part Six

Roger reveals how Dan Dare co-creator Frank Hampson was thorn in Leonard Matthews side…

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part Seven

Trouble at the top for ‘The Management”, the troubled debut of Boys’ World – and the demise of Ranger

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part Eight

On the creation of Martspress, the company that would publish TV21 in its later, cheaper incarnation – and reveals an intriguing mystery surrounding some art commissioned by the company…

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part Nine

Moving from the sublime to the ridiculous, Roger recalls how Men Only was given a new lease of life – and Leonard Matthews’ ignorance of Star Wars…

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part Ten

A phone-call out of the blue brings about a closer relationship with the one man Roger had once feared the most…

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part Eleven

A search for elusive promotional film stills end in the middle of nowhere in a one horse town without a horse – and Eagle‘s production methods are recalled

[divider]

This biography of Leonard Matthews, which is being published in a total of twelve parts, has been put together using material from Leonard Matthews’ obituary as written by George Beal for the Independent newspaper dated Friday, 5th December 1997; and a piece authored by Jack Adrian (presumably aka Christopher Lowder); Living with Eagles compiled and written by Sally Morris and Jan Hallwood (particularly pages 219 to 222); David Slinn’s research notes during 2005 in connection with the authoring of Alastair Crompton’s Tomorrow Revisited and from Brian Woodford’s association with Matthews at the Amalgamated Press between 1955 and 1962. Entries also come from both Wikipedia and from the internet under the heading Fleetway Publications.

Further pieces have been taken from Eagle Times as and where identified; the blog-spots of Michael Moorcock’s Miscellany (particularly 9th and 10th April 2013) and Lew Stringer’s Blimey! where he refers to the Top Spot magazine. The remainder is from my own personal association with Leonard Matthews between the years of 1978 and 1991.

Artist, designer, photographer and writer Roger Prölss Perry was the youngest of three children – the given name of Prölss deriving from the maiden name of his paternal German grandmother.

Born in Guildford, Surrey in July 1938, after school he studied at the Regent Street Polytechnic School of Art close to Oxford Circus, the West End and the BBC where he achieved the National Diploma in Arts and Design before commencing with a further year of study in commercial design under the guidance of Ley Kenyon DFC, noted for his writing, art and underwater photography, and lithographer Henry Houghton Trivick (1908-1982).

His first job in the media industry was as an in-house illustrator on Farmers’ Weekly, beginning in March 1959, working under the direction of Art Editor Alfred Harwood, working on the seventh floor of Hulton House at 161-167 Fleet Street, London. He was there for just five months before going into two years of National Service until August 1961, returning to the company (now Long Acre Press) as a layout artist (designer) at “Juvenile Publications”, the umbrella name for Eagle, Girl, Swift and Robin. He joined the team of three other layout artists – Bruce Smith, Ron Morley and John Kingsford – on Monday, 28th August 1961 where he remained until May 1966.

He then began work as Art Editor at Century 21 Publishing until June 1969. As he says: “Yes, I suppose I could be described as a ‘layout artist’ but I commissioned art (Art Editor), kept an eye on Andrew Harrison and Bob Reed (Studio Manager), took photographs as and when needed (Resident Photographer) and generally made sure that everything was present and correct when everything needed was being sent to the printer (Office Boy). I also (with the help of Linda Wheway) came up with the ideas and photographs for five books (Author?)”.

From Century 21 Publishing, Perry then went to Hamlyn Books (July 1969 to October 1970); and worked for Bob Prior’s premium packages for two months before joining ex-Art Editor of Century 21 Publishing Dennis Hooper in December 1970 who was now Editor of Countdown at Polystyle Publications.

Perry remained with Polystyle until September 1974, when he became Art Editor for Purnell Books, remaining with the publisher for eleven years – until 1985 when he started operating his own public relations business.

Due to his growing interest in the art and the close proximity of Bath where the nerve centre of the Royal Photographic Society is, he achieved the distinction of Associate Member in 1987 for audio/ visual presentations thus entitling him to display the letters ARPS after his name… although he rarely does.

Having had a life-long fascination for the Far East, he moved to the Philippines in the 1990s, where he married Marilyn Gesmundo. He lived for 11 years on Cataduanes before moving a number of times recently following Typhoon Haiyan, finally with Raquelyn Navarro in the city of Naga in Cebu.

Sadly, Roger died on 23rd July 2016 following a heart attack, just one day after his 78th birthday.

He is survived by his daughter, Rae. His son, Marcus, predeceased him after a long battle with cancer.

Categories: British Comics, Creating Comics, Featured News

Rebellion announces new Battle Action mini series – our guide to the returning strips

Rebellion announces new Battle Action mini series – our guide to the returning strips  Replacing Eagle: The Comics That Didn’t Make It – Part 4 Another Eureka

Replacing Eagle: The Comics That Didn’t Make It – Part 4 Another Eureka  Replacing Eagle: The Comics That Didn’t Make It – Part 3 Eureka

Replacing Eagle: The Comics That Didn’t Make It – Part 3 Eureka