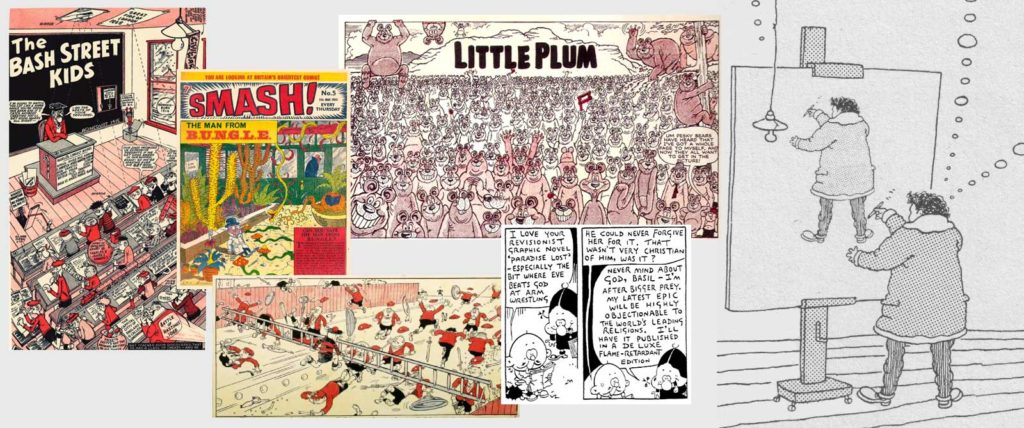

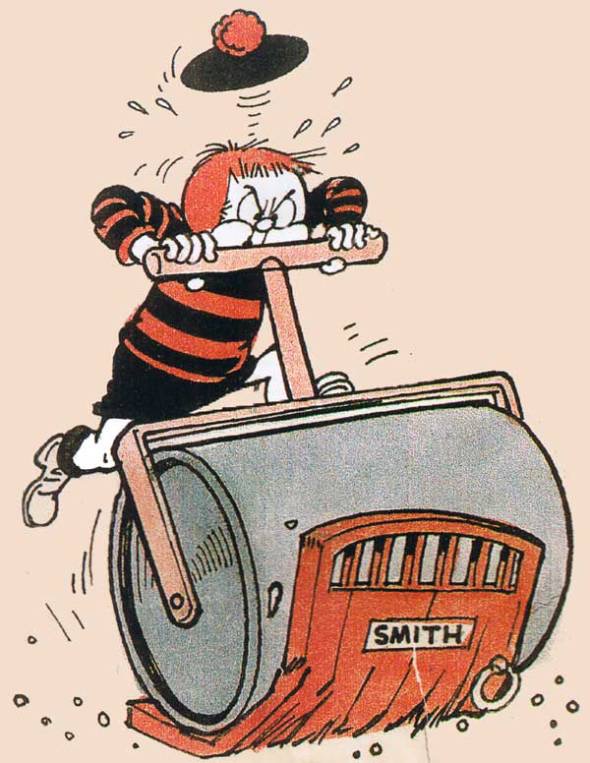

A montage of Leo Baxendale’s work, including part of his self portrait

First published in October 2017 on the inexplicably and ruthlessly pruned Forbidden Planet International blog, an act of cultural barbarism about which Forbidden Planet (Scotland) Ltd has yet to reverse, we are delighted to republish, as first published and with the permission of author Pádraig Ó Méalóid, comic creator Leo Baxendale’s last-ever interview, discussing his childhood, early career and first work for The Beano.

The interview was originally edited for publication by Joe Gordon

Leo Baxendale

In April 2017, Britain lost one of our most gifted and influential creators in the rich heritage of British comics, Leo Baxendale, passing away at the age of 86. Or I should say physical age – I had the enormous good fortune to count Leo as a friend, and to swap emails with him regularly, talking about good books, comics, film that we liked, and bonding over our shared love of animation; it was clear to me that the Master of Bash Street may have been in his eighties in body, but in his boundless spirit, his expansive imagination and his joy at encountering new works (or revisiting classic works he had loved), he was still vibrantly young.

Leo’s legacy was not just in his remarkable works for both children and adults (and, like all the finest authors he approached his work for younger readers with as much rigour and respect as he did for more adult work), his influence spills out far beyond those works – many are the now much-lauded giants among Brit comic creators who happily bow to the influence of Leo’s work, not just the hugely imaginative and energetic art style and humour, but the sense that came with them, the questioning of authority and, one of Leo’s eternal enemies, almighty power, that permeated their young minds as they read them and would, years later, influence their own work, which in turn has gone on to influence yet another generation. It makes me smile to think of that influence, that attitude and style and way of thinking, being passed along the generations of creators and their readers.

A little while back, Pádraig Ó Méalóid talked with Leo, but for various reasons we were not able to run the interview at the time. Now, several months after we lost Leo, on this day, which would have been his birthday, we would like to present this piece, a journey back to a different time, the era and events and people that shaped young Leo, from parents and siblings to a kindly teacher, long, long gone, but still fondly remembered for his encouragement and influence (how many of us have similar memories, how many of us were shaped in such ways at a young age by a good teacher, librarian, family member?).

We present this as a mark of respect on his birthday for a much-missed friend and creator, some last words from Leo. Over to Pádraig and Leo. (Joe)

Leo with his powerful and determined Minnie the Minx. Photo: Gloucestershire Live

Pádraig Ó Méalóid: Where and when were you born?

Leo Baxendale: My mother was a spinner, my father a weaver. I came into the world with stubborn slowness, my mother being twenty-six hours in labour. I was her first born. When I emerged from her womb, it was October 1930, and the time of the Great Depression.

Here at Whittle le Woods we lived in the very hem of the skirt of the Pennines. The domain of my infancy was a terrace of stone built houses, its raw red Whittle sandstone, from the quarry once worked by the Romans, weathered to grey with warm pink and ochre shading. Beyond lay the coastal plain of Lancashire.

My father’s mother bore twelve children. Four of them, “fat, bonny bouncing babies,” were carried off by the smallpox, leaving eight to grow to adulthood and to marry. My father was the youngest of the eight, and named after Pope Leo XIII.

I was named after my father, Leo Baxendale.

PÓM: You were the first born of how many?

LB: I was the first born of six. That would have been seven, but my brother John, born in 1935 on the night of the Sunday after Corpus Christi, died at birth. These were bad times. There was no doctor on duty at the infirmary, and none could be found.

My mother pleaded with the nurses to call a priest to baptise her dead child, but they refused, turning coldly away. When the morning shift came on, my mother pleaded with them, but they too turned away. These were bad times. That week, on two wards, fourteen babies were born and six died.

My mother spent the rest of her life worrying and wondering, if her unbaptised baby John was wandering lost in Limbo.

Whittle-le-Woods. Image via Chorley’s Inns and Taverns

PÓM: Your mother was a spinner, and your father a weaver. Were these common trades in that area?

LB: It came by stages. The spacious coal cellars of the terrace at Whittle had once been the workshops of individual hand loom weavers: they wove cotton. The cellars of the terrace at Bamber Bridge where my mother was born, had been likewise. There were many similar cellars in many terraces elsewhere, and there were many elsewheres.

My great-grandfather John Baxendale was a hand loom weaver in that first stage. His wife Martha died when her fourth child was a month old. John left the district and the children were dispersed, taking the names of the families they went to. They took back their own name of Baxendale when they married.

From May 1980 to May 1987, I carried through a High Court action over the copyrights in my Beano creations. In the midst of this, I travelled north to my mother’s at Preston in May 1983, to research a book [an autobiography], Pictures in the Mind.

Here I was, back at Whittle outside the church and school of St Bede, places of my infancy, while a local historian showed me a stone building that I had never given a second glance to as a young child, but it and its kind belonged to that second stage. Here twelve hand loom weavers had worked under a master.

My cousin Cissie, older than me, who had escorted me to my first day at St Bede’s school, was a part of that third stage, vast mills powered by steam, that loomed over the terraces of the workers. Cissie was a weaver of the finest cotton, for export, and had kept a small piece, fit to grace a spider’s web.

In 1941 she was given four choices of war work: the forces, the land army, munitions at Euxton, or Leyland Motors. She chose Leyland Motors, working as driller, miller and grinder on fuel injectors for the engines of tanks, and on transmissions.

Cissie told me: “It was the best five years of my life during the war. I had been so hemmed in; my parents were strict. I had only seen Whittle. I got my freedom when I went to Leyland. There were girls from Preston, Chorley, Bamber Bridge, Charnock Richard. The girls from Preston had a broader outlook on life. I got education at Leyland Motors; I made friends from all over.

“There were dozens of people I wouldn’t have known otherwise. I’d be working with a lad and he’d come in and say ‘I’ve got my calling up papers.’ We’d all go for a drink with him at the Motors club; but at home I couldn’t tell. My mother would have belted me; but the people were just as good as us. Another girl from Whittle, Eva, told me she told lies too: we had to. We couldn’t come home and tell the truth.”

PÓM: What about your siblings? What did they end up doing?

LB: That my siblings and I came from the same womb, weighed little when set against what must follow. We were born into the working class. The working class is a construct. It was made by a system of almighty power and almighty absurdity. That same system steals worth from people and replaces it with the false coinage of status.

On 4th April 1876 there had been sudden unforeseen death, that caused my mother’s forebears to be thrown into disarray. The history of that calamity was carried forward by daughters and grand-daughters, with a perception of lost status.

When my mother married, she set out to regain lost status with the only means open to her – through her offspring; so that when I and my three sisters and two brothers reached adulthood, we lived scattered and afar, wherever professional work took us, wherever the winds blew us. This was ambition-by-proxy at work.

In the 1960s my brother Richard was being trained to become a Jesuit. At his last visit to us he was enthusing about Martin Luther King. But then a change in the direction of the political wind blowing through the Vatican caused hundreds of disillusioned young Jesuits to leave the order.

Richard, distraught: “But where will I go?””You can come to stay with us, Richard”.

But Richard didn’t come to stay with us. After climbing Mont Blanc with a group of Jesuit fellow mountaineers, Richard used his rucksack on the descent to toboggan down the ice slopes, waving to his companions, then plunged to his death in an unseen ice ravine.

Twenty years on from Richard’s death my mother was still mourning the loss of dreams: ‘If Richard had lived, he would have changed the Church.’

PÓM: What sort of memories do you have of comics when you were a child?

LB: Unemployed, searching for work, my father set out to learn to drive: that is, to drive every class of vehicle. He cycled every day to Jameson’s bakery at Gregson Lane near Bamber Bridge. Jack Jameson, married to my mother’s sister Monica, drove one of the vans for his father’s bakery, and taught my father to drive on the bread round.

A friend at Whittle, Frank Longton, drove lorries and pleasure coaches for a Chorley firm. He taught my father to drive a coach in the second winter of my father’s unemployment, when the coaches were laid up out of season. Since Frank could only do this after his working hours, my father learned to drive the coach by dark winter nights.

On the day of the driving test my father needed a vehicle. He asked a young man up the road who had a motor lorry if he could borrow it for the test. The young man was agreeable, but not wanting to fall behind with his deliveries, he asked that the lorry be taken out loaded up. My father had never driven a lorry before, but passed his test driving a lorryload of coal.

A further spring and summer of unemployment went by; then in late 1936 an escape route opened. The family GP Dr. Maguire, a wiry old Irishman, asked my father to move to Chorley to be his chauffeur. We were receiving thirty-five shillings a week on the dole. Dr. Maguire offered a wage of thirty shillings, plus a weekly joint of beef (bought cheaply by the doctor on Chorley market). We went at once.

Whenever my father visited Whittle, he took me with him. My cousin Harry bought Chips, Comic Cuts and Film Fun every week, and stored them in immaculate separated piles in a deep sideboard drawer. From each visit to Whittle, I returned weighted with Harry’s hoard. Appetite sharpened by abstinence, I devoured the feast at a single extended sitting: Film Fun with its double-page spreads of Laurel and Hardy, and Joe E Brown.

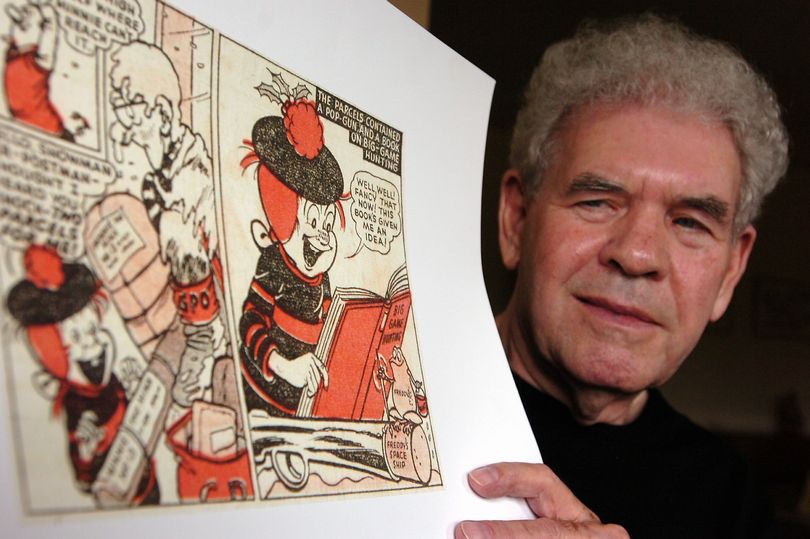

A panel from a “Laurel and Hardy” story for Film Fun published in 1938

Joe E Brown as Osgood Fielding III to Jack Lemmon as Daphne at the end of at the end of Some Like It Hot: “Nobody’s perfect”

Laurel and Hardy, George Formby, Wheeler and Woolsey, and Joe E. Brown were drawn by George Wakefield. I didn’t know his name, because the drawings were unsigned, but I could tell when the strips were taken over by another artist, and the life went out of them (George Wakefield had died).

The comics from cousin Harry were never enough to satisfy. From late 1937 onwards, whenever my mother had a disposable twopence from the household treasury (which was not every week, but often enough) I bought myself, not comic-strip comics aimed at my own age, but the DC Thomson story papers Wizard or Hotspur that were aimed at 14-year-old boys, or the Amalgamated Press boys’ paper Champion. Absurd plots; tight and rigorous writing, free ranging imaginations at work; magnificent titles – “The Giant Gun That Shook The World”, a tale of Afghan tribesmen building a siege gun that could lob a shell from Kabul to the House of Commons at Westminster.

1938 being the second year of my father’s employment with Dr. Maguire, he asked for a rise, and was given an extra five shillings, so that we were finally brought up to the level of the dole. The doctor cancelled the weekly joint of beef.

On a day at the beginning of September 1939 I walked into the kitchen. My parents were listening to the wireless, but in a strange way. They usually listened sitting down, but today my father and mother were standing formally, very upright, and facing each other from the two ends of the mantelpiece.

My father’s right hand rested on the mantelpiece, and my mother’s left hand the same. From the wireless that was placed equidistant between them, came the reedy voice of Neville Chamberlain: “…I have to tell you now that no such undertaking has been received, and that consequently this country is now at war with Germany.”

Dr. Maguire asked my father to stay with him for the duration of the war at his house on an island in Lough Melvin in Ireland. My father wasn’t having any of that. An advert appeared in the paper for a post of chauffeur gardener in the village of New Longton; my father was interviewed, and got the job.

Our parents gathered us together: “There will be bombing of towns, and we live next to the railway station. We’ll be safer in the country.” We moved in October 1939.

We were migratory birds at New Longton. After one year there, and as my age changed from single digits to 10, my father took a job as a lorry driver at the village of Longton.

My parents bought a house at Longton, semi-detached. With the death of my father’s parents, and the terraced house we had lived in at Whittle being left to my father, the money from the sale of it went towards the cost of the house at Longton; the rest on mortgage.

Sidled up close to our semi was a large detached house owned by Dr. Sharpe, Health Officer for Preston, and his wife, who took to her bed in mourning for her proud eldest son Richard, killed early in the war.

My father came home from the first day at his new job full of anger. Driving lorryloads of ashes from the Ribble Power Station to runway construction at a new wartime airfield, he had been approached by the runway contractors to take part in a fiddle: to pretend he had taken to the sites more loads than he had actually delivered, and he angrily refused.

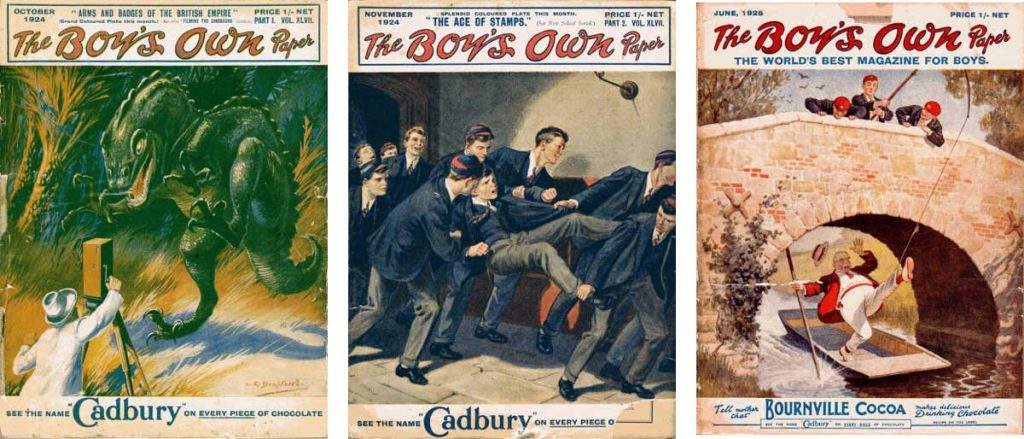

Mrs Sharpe allowed me to go up to her dead son Richard’s empty bedroom, and read his bound volumes of Boy’s Own Paper. There they were on the shelves, big volumes bound in fine black leather, and with pages of fine white paper, much finer and whiter than the Wizards and Hotspurs I had read at Chorley.

Covers of Boy’s Own Paper from the 1920s, via the British Juvenile Story Papers and Pocket Libraries Index

The volumes were from the 1920s and early 1930s. The stories were curiously different from the Wizard and Hotspur adventures, and featured young men with “cricket-hardened muscles.”

One story was set in Egypt: a group of young white men with cricket-hardened muscles had a houseboy, Selim. Selim was captured by bandits, or terrorists, or subversives or whatever, and they gave Selim an orange to slake his thirst. The orange was full of ants.

The core of the plot: the young men with cricket-hardened muscles thought that Selim had betrayed them. In believing that, they had wronged him.

As I read the story, it was clear that the author had intended Selim to be a figure of fun, but that somehow, in the writing of it, he had given Selim all the best lines.

It is a curious thing, that after more than 70 years, I can remember nothing of those young men with cricket-hardened muscles, neither their names nor anything about them.

But I remember Selim.

I read all the volumes. It was a great feast. Then, later in the year, in the heat of midsummer, on a hot and drowsy day, I went next door. Mrs. Sharpe was sitting in the garden in the dappled shade. She looked at me incredulously: “Do you mean to say you want to read on a day like this?” I just stood there, and after a moment Mrs. Sharpe waved her hand wearily towards Richard’s bedroom, and I went upstairs to the books, to start on them all over again.

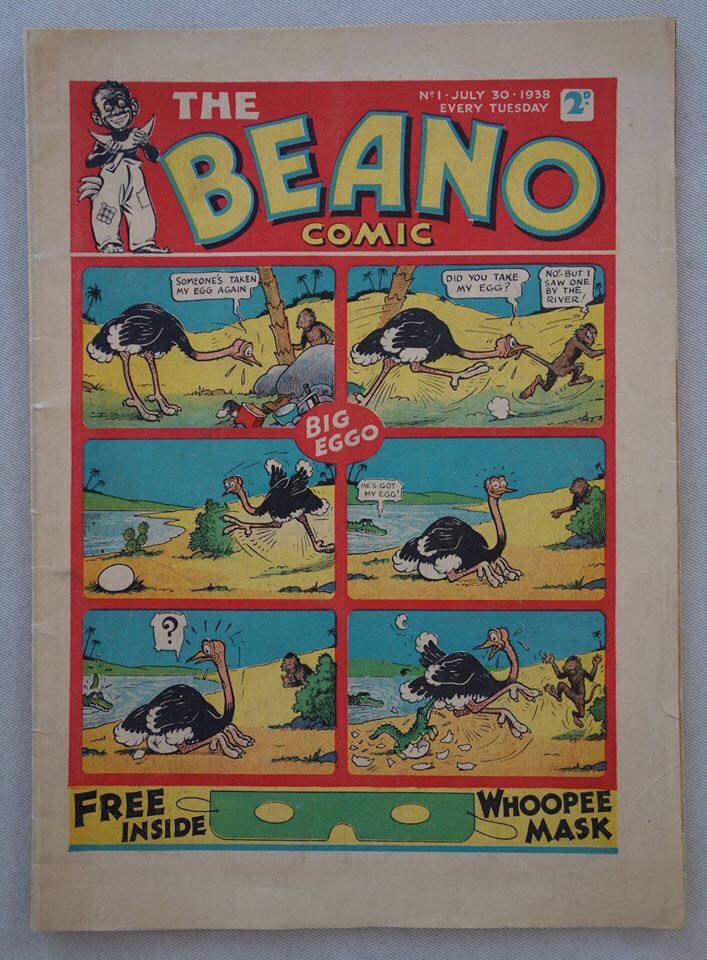

PÓM: By the time you are talking about it was a few years since DC Thomson had first published The Dandy and The Beano, in 1937 and 1938. Did they make any impression on you at the time?

LB: Tuesday 26th July 1938: a brilliant sunny day at Chorley. I stood in the playground of St Mary’s elementary school, doing nothing in particular, while all around was clamour. I was seven. This was a day in history to note, though I didn’t know it.

An older boy rushed up and thrust a comic into my hands: “Look at this!” I studied the comic politely, then handed it back, and he rushed off. The boy had just shown me the first issue of The Beano, published that day; but I was disconcerted by a comic that had an ostrich, Big Eggo, on its cover.

1938 and the first issue of the Beano arrives – complete with some art on the masthead that wouldn’t be acceptable today, thankfully – how could a young, schoolboy Leo know that in the years to come he would not only create for this comics institution but craft characters that would last generations?

In January of 1942, in the dark days of the war, I walked down School Lane at Longton and into the Church of England school to sit for the County Scholarship. I was part of the tiny percentage of working class children allowed to pass through the gate, to go beyond the rest who were left behind.

From my bedroom window I could see the cupola of Hutton Grammar School, at a distance of half a mile as an undistracted crow might fly. If I walked a twisty path across the fields, then over the single-plank bridge with green painted iron handrail across the County Brook, that slid dark and silent between field boundaries to the estuary marshes, I came to the sports fields and boundary trees and the school itself, copper roof tiles turned pale green, and white cupola.

However.

On the day we heard that I had won the County Scholarship to Hutton Grammar School, my father and mother told me that they were forbidden by the Catholic Church to send me to a non-Catholic grammar school.

Later in that same month of January, I sat for the entrance examination to Preston Catholic College, a Jesuit college.

I began at the Catholic College in September 1942.

When George Wakefield had died on 12th May 1942 and the life went out of Film Fun, I began to read The Dandy and Beano instead, published on alternate weeks (paper rationing). I was buying these two comics for the sake of one page each – Desperate Dan and Lord Snooty, created by Dudley Watkins. It struck me that Lord Snooty and his Pals was an amalgam of the 1930s film Little Lord Fauntleroy and the Our Gang series of 1930s low budget shorts.

It wasn’t that comics mattered to me in particular, and it never crossed my mind that I would become a comic artist; it’s just that whenever I came across a creation with a strongly beating heart, I looked at it more closely.

Money was tight in 1944, so for the Lancashire Art Exhibition I took my painting that had been exhibited the year before, turned it over, and made a new painting on the back.

By my 14th birthday at the end of October, it would have been hard to say which mattered more to me: drawing and painting, or comedy. Comedy could carry a heavy cargo, yet ride high in the water.

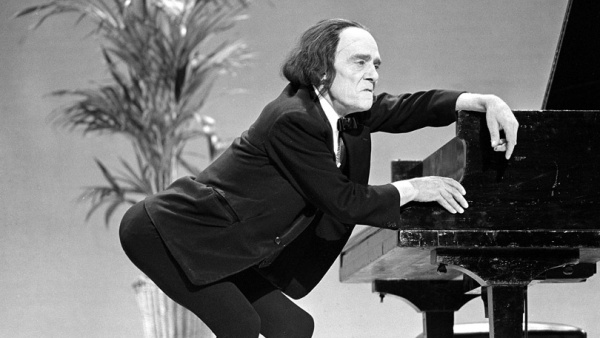

At the end of the following month, Max Wall suddenly came on the wireless as a star of a new series, Hoopla, and I felt exultation. I seized on Max Wall’s surreal sly drollery, the absurdist comedy that fed on lashings of toast, simply ooooozing with butter. I had never met anything like this before.

But Max Wall at once unsettled my father; who was loud in derision, and reached over to switch off Max Wall.

(34 years on from this, in May 1978, Ian Dury gave his first major London concert, at the Hammersmith Odeon, to an audience of punks. They were told to ready themselves for ‘one of the jewels in England’s crown’. On came, not Dury, but his hero Max Wall. Max Wall at once unsettled the audience; they were loud in derision, and barracked him, trying to switch him off; until Ian Dury stormed on and told them to shut up and listen; so they did.)

Legendary comedian and actor Max Wall

My father, though, couldn’t switch off Max Wall as one week followed another, because he had to go to work at the power station, where he was Leading Stoker. To be a Stoker at the power station: eye-straining, nerve-straining, nervous energy draining; standing, nerves taut, before a wall of dials and instruments, constantly exercising judgements on the feeding of the beast by remote control of the great hoppers, always watchful, always fearful of overload.

To be Leading Stoker: overseeing, directing the team of men in the delicate, watchful enterprise, to be the one responsible.

My father worked double-shifts: the day shift as Leading Stoker from 3pm to 11pm, then straight on to the night shift as “Ashes Attendant” from 11pm to 7am – sixteen hours non-stop.

“Ashes Attendant” meant “rodding” – clearing the ashes from the furnaces. My father fed the beast by day and cleaned it out by night.

In late May of 1947 we were studying A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The senior English master was James Lawson, with a deformed back, ill, and unvaryingly courteous.

I loved the language, to understand it, and to know its structures. I felt gratitude to James Lawson, for his generous teaching, and for his courtesy.

On an impulse, I decided to draw a set of sketches of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, to give to James Lawson. It was a weekend, and I was rested, and fresh, and the sketches “came right”. I pencilled lightly on delicate Michalet paper, and finished in line and wash: a fine Indian ink pen line for the characters, and elusive watercolour washes to serve for the greenwood.

On the Monday I placed the set of set of sketches in James Lawson’s hands. He studied them for a long while, then made to hand them back, but I said “No, they are for you.”

He must have taken them, straight after class, to show around the common room.

At the lunch hour I was confronted by Miss Meagher, the art teacher. Miss Meagher spoke to me, but her eyes were blank, and her face was as stone. She asked if I would borrow back my Midsummer Night’s Dream sketches from Mr. Lawson, so that she could put them in the annual College Art Exhibition in June. I looked at her face and felt unease. I was being used, but was uncertain what to do.

I looked back on this in later years. If I had possessed then the wherewithal of an adult, the learned skills of knowing how to protect myself and others against the rage, I would have replied to Miss Meagher that though I had drawn the sketches, I had given them to James Lawson, they belonged to him now, and it was for him to decide, not me.

But I wasn’t an adult. I was sixteen.

James Lawson, troubled, placed the sketches in my hands: “Ask Miss Meagher if she will please use drawing pins, or put just a touch of glue at each corner to mount the sketches. The paper is so delicate, if she puts glue all over they will tear when they are taken down.”

I gave this message to Miss Meagher, with the drawings. She said nothing in reply, but walked away with the drawings, and I again felt unease.

At the exhibition I had been given one wall of the assembly hall, as I had made 30 or so drawings. Miss Meagher had added the Midsummer Night’s Dream sketches, and I saw that she had glued them completely to the wooden exhibition boards.

At the dismantling of the exhibition I went to collect the Midsummer Night’s Dream sketches from Miss Meagher. As I stood by helpless, she reached out, seized the sketches each in their turn, and tore them from the mountings, so that pieces of the delicate Michalet paper were left stuck to the wooden boards.

I had thought then that James Lawson was in his late thirties, possibly early forties; but I was wrong: that was illness. James Lawson and his three sisters had all been sent to grammar school, and it had impoverished the family. James Lawson died suddenly of pneumonia in February 1963 at the age of 42; so that when I gave him the Midsummer Night’s Dream sketches in May 1947, he was in reality twenty-six.

When I gave the destroyed sketches back to him, I felt shame. I told him that I would draw a new set; but I didn’t, I couldn’t: after the exhibition came the school year’s end, and the end of my schooldays.

I left, to go wherever the winds would blow me.

PÓM: What sort of schooling did you have as a child?

LB: My father spoke with anger of his childhood attendance at the village school of St Bede, the wasted years of “playing with clay”. He was full of anger at the thought of the same thing being visited on his children. In 1935 I started at that same school of my father’s bitter memory. Each evening he asked me what I had done at school, and as I answered “playing with clay,” he repeated the words with derision.

I had been 18 months at St Bede’s school and had learned nothing. At our move to Chorley the young women teachers of St Mary’s infants class were appalled that I barely knew the alphabet: they gave me a crash course.

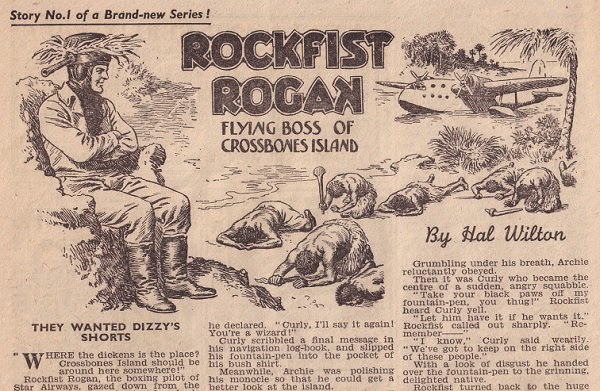

“Rockfist Rogan” from The Champion Issue 1471, cover dated 8th April 1950. With thanks to Jeremy Briggs

“Rockfist Rogan of the RAF” began in Champion in October 1938, created by Frank S Pepper (20 years later he created Roy of the Rovers). In October 1939 I wrote an essay on Rockfist Rogan. The teacher of my class, Mrs Kidd, had taken lately to holding up my essays in front of the class as examples to be followed. On this day, she held up my Rockfist Rogan and made a great hoo-ha.

The headmaster, Mr Twist, was brought in: there was a show, a great theatre, put on for the class and for the headmaster, as Mrs. Kidd moved about the room holding up my essay, with pan-pipes and roundelay. The next day I was transported along with another boy to Mr Twist’s class. I was puzzled at being plucked from our fellows, and could see no logic in it.

I sat with my companion in a clamorous cavern of older boys. The headmaster roared up, whacked papers on our desk: “Do those”. I stared at the arithmetic problems in front of us. My companion whispered: We’ve never been taught how to do these. What are we going to do? We sat frozen, mute.

Mr. Twist roared up: “Haven’t you done those yet?” then roared off again. The day had turned into a nightmare. At the long day’s end I walked home in dismay. There would only be a night’s respite. It would start all over again tomorrow. My mother turned to greet me: “We are leaving Chorley. Your father’s got a new job.” Unbelieving relief welled up in me. Next morning I slid into the seat beside my companion and announced triumphantly: “I’m leaving. We’re moving.” He looked at me in pale dismay: “What will I do?” I left that day. In later times my thoughts went back to the companion I had left alone in that clamorous room.

On my first day at St Oswald’s school at Longton, pieces of graph paper were handed out, and we were instructed to make drawings which followed the contours of the little squares. I looked at the graph paper. This was easy. I flicked in a battlecruiser. Finished, I looked around the room. The others were looking blankly at their squared papers. They didn’t know what to do. I felt angry. I had been doing this sort of thing since infancy. Why hadn’t the teachers shown the others what to do? Why hadn’t they shown them how to start? The papers were collected, and the teachers held up my perfunctory drawing before the class and made a great hosanna and chanticleer. I still felt angry. Why had they left the rest of the class to flounder?

In January 1942 I walked into the Church of England school to sit for the County Scholarship. As my pen raced across the papers, I knew what I was doing: I was showing off, showing off to the examiner whom I would never meet.

Father Malone, an ancient Jesuit whose face always seemed to be in shadow, was Headmaster of Preston Catholic College. Two or three weeks after our first term began there was high excitement in 1A: Father Malone was to take us for one period, to test our progress. It was a great privilege.

Father Malone began; and I noticed two oddities. The questions were ridiculously easy, and he did not address them to any particular boy, but to the class in general.

The confluence of these two oddities produced a forest of eager waving crimson-blazered arms, until the Headmaster singled out one to answer.

I went along with the rest for the first two questions, then thought this is silly. I decided that if I was asked a question directly, I would answer it, but that I would not join in the frenzy. I sat back to wait.

At each question the frenzy increased in intensity, stomachs pressed against desk tops as bodies strained forward, arms pushed forward horizontally in parodies of Nazi salutes, my classmates screaming “Father, Father.”

I sat still, ready to answer if asked.

Father Malone never asked me, nor even glanced at me.

The electric bell signalled the end of the period; Father Malone moved towards the door. At the last moment, about to leave the class, he turned and looked back at me with a sly corrupted smile: “You weren’t trying very hard, Baxendale.”

My father sat in his chair, staring into space, silent; then suddenly burst out: “Why aren’t there any miracles nowadays, then we would know?”

It was six hundred years since the natural philosophy of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries had been in tension with the notion of miracles, and people then had taken note that miracles were claimed for past times, but were absent in their own time. Yet six hundred years later here was my father, with a struggle between credulity and incredulity in his exhausted being, trying to make sense of his exhausted life.

In the Fourth Form, realisation came that I couldn’t bear it, and that I should not any longer be a burden on my father’s back as he worked double shifts at the power station. I didn’t articulate this in language in my mind, as I articulate it to you now. It was a consciousness strongly felt, not a process of ordered thought, and I didn’t talk of it to anyone. I would leave the College at the end of the Fifth Form.

In the upper forms Greek had been added to the curriculum. I had found Latin pleasant enough, and Greek had a melody to it; but I made an abrupt decision that a second dead language would be excess baggage. At the Mock School Certificate, I put my name on the Greek exam paper, and handed it in, blank.

I was summoned to see Father Malone. He stood before me in his study, angered, affronted: why had I handed in a blank paper? People did not hand in blank exam papers. Why had I not written something?

I told Father Malone that I would not do Greek. He probed at me with words, shifting the direction of his interrogation; but I refused to be drawn into argument, simply repeating that I would not do Greek.

Father Malone stood immediately before me, but as I spoke to him, my eyes were looking past him:

Mme Coutourier, the School Secretary, Father Malone’s right-hand-woman, sitting at her desk, had stopped working, and had turned in her chair to watch me.

Therese Coutourier had olive skin and high cheek bones. Thinking about Therese Coutourier, lean and dark, I had judged her to be in her thirties. I was mistaken. She was in her early twenties.

I became aware, from an alteration in the tone of Father Malone’s voice and in the stance of his body, that he was giving way, that there was acceptance. He gave up.

PÓM: What about art? You mentioned that you “had been doing this sort of thing since infancy.” Was that in school, or at home?

LB: In my infancy at Whittle, I sat and drew at the kitchen table, and was joined in this activity by my father or mother variously as each had time.

When my mother had to work at the table, I moved to the window and used the broad wooden sill as my drawing board, looking out across our steep back garden to the Cut, with now and then a passing barge.

I drew each day in the blank stop-press columns of the Daily Express.

There were other expanses for me to draw on, that were much broader than the stop-press columns. The pram, our deep-bellied galleon, was as valuable as any hired fleet of Venice. My mother at marriage found the small shops at Whittle dearer than the Co-op. The nearest Co-op was at Walton-le-Dale, between Bamber Bridge and Preston. They didn’t deliver to Whittle. My mother was travelling to work daily at the New Mill at Bamber Bridge, so this was her stratagem: she sent her weekly order to the Co-op, who delivered it to her mother’s house at Bamber Bridge.

My mother stowed the order in the hold of the pram, below the sliding wooden panels: she found that by skilful stowage the pram could take over forty pounds weight of food (twenty kilograms); though the three mile walk home to Whittle was a stiff journey: uphill all the way; and my mother was chesty (asthma).

After I was born, and my mother stopped working at the mill, she still made the weekly journey to Bamber Bridge to collect the Co-op order; but now I was tucked into the pram above the cargo.

All the things in the Co-op orders were wrapped in large smooth pale buff paper sheets, and I thus had an unending weekly supply of sheets of paper to draw on.

Beyond all this, I had a yet greater expanse for drawing on. The wall alongside the staircase being distempered, the palest green, I covered it with drawings from top to bottom of the stairs, my parents taking care to provide me with plenty of pencils for the purpose.

Barges hauled by boat horses brought coal to my grandfather’s coal yard from the Wigan coalfields to the south. At the end of our terrace the canal broadened out to a basin where the barges could dock and turn. A wharf on the opposite bank from my grandfather’s coal yard unloaded coal for the steam engine of the weaving mill; and there was the stone-wharf, built for the loading of millstones from Whittle Quarries.

Yet it didn’t occur to me to draw any of this, any more than I thought to draw my grandfather’s great black mare pulling wagon loads of coal past our house. I drew from the imagination, or things from the greater world that I had seen in the newspapers: biplanes or ocean liners or such. I must have thought that my own world was ‘ordinary.’

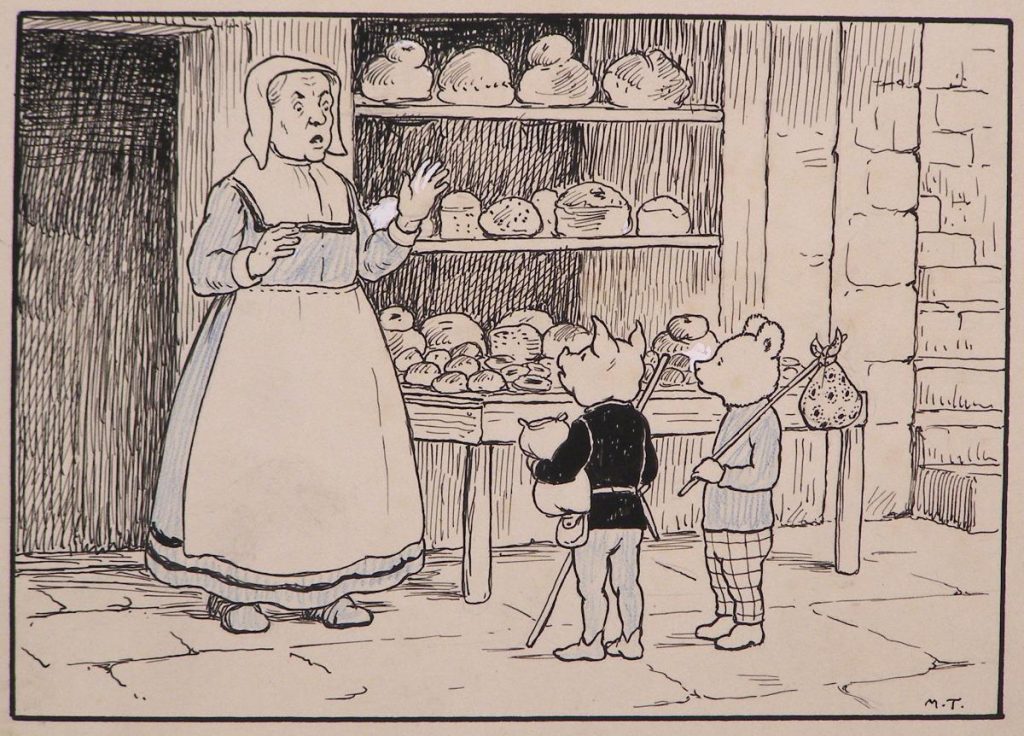

A panel from “Rupert and the Little Prince” by Mary Tourtel, first published in 1930

Every day I looked at the Rupert Bear drawings by Mary Tourtel. One fine day I was standing on the pavement edge surveying my domain, while behind me my mother stood at our front gate. I saw the postman approach her holding out a flat parcel, but she pointed silently to me, and the postman walked over and placed it in my hands. It was a Rupert book.

At Easter 1935, at the age of four-and-a-half, I set out, escorted by my cousin Cissie, to my first day at the dead zone of the elementary school of St Bede. No drawing there.

PÓM: What were you good at in school?

LB: I can’t very well answer ‘everything’, in part because of meddlesome circumstance, and in part because of my own arbitrary decisions.

You’ll recall my words in answering your seventh question: “In the Fourth Form, realisation came that I couldn’t bear it, and that I should not any longer be a burden on my father’s back as he worked double shifts at the power station. I didn’t articulate this in language in my mind, as I articulate it to you now. It was a consciousness strongly felt, not a process of ordered thought, and I didn’t talk of it to anyone. I would leave the College at the end of the Fifth Form.”

At the Catholic College, my fellows had told each other ‘grammar school boys join the RAF’, so when it came my turn at 18 for National Service, that’s what I did.

In my first week of basic training at Bridgnorth the padre Squadron Leader White-Spunner told me he had looked in my file, and that I was marked as potential officer material.

A day or two later, I was called for an interview. The Squadron Leader i/c Pointless Interviews looked down at my open file: “You have a first class academic record; but you don’t have maths, and we are a technical service.”

I told him I understood.

He looked across the desk at me: “You should have gone into the army. They would have made you an officer automatically. But you see, we are a technical service; we must have maths.”

I told him that I understood.

In my years at the Catholic College I had never done maths homework. Never.

By the time of the Third Form, I came under intense combined pressure from Charles Kinleside the maths and science master, a kindly but distracted man; from the Jesuit form master Mr Maher, and from my parents.

My class had three or four boys who were renowned for their brilliance at maths. I thought in passing that was enough mathematical renown for one class; but to head off the harassment I decided I had better do something about it, just pro tem.

Later Charles Kinleside stood before the class and announced the results of that year’s maths exam: I had come fourth. He spoke to me across the classroom in bewilderment: ‘You see, you can do it if you want to’; but there was the rub. You can do it if you want to.

I was perfectly numerate for everyday use, and for any foreseeable task I might encounter in my future professional work. If it ever happened that I should need specialised mathematical skills, I would call on someone who had them.

At my final exams at the Catholic College, the School Certificate, I didn’t take the maths paper, any more than I took the Greek.

The Squadron Leader looked down at my file again, intently, softly tapping the fingers of both his hands on the desk, pondering a problem to which I knew there was no solution.

As I looked about me in the RAF, and identified the grammar school boys, I saw that those who had stayed on to the Sixth Form became education sergeants, and the ones who’d had the means* for university were made officers (* this was before the short-lived post-war ‘welfare state’ – there were no grants to go to university); and full realisation came, that in making the decision to leave grammar school at the end of the Fifth Form, I had stepped outside the system, forever.

PÓM: Did you do any form of national service, then?

LB: During two months of basic training at Bridgnorth, I did no basic training, no drill.

I spent the time painting posters for the Education Officer (typical example: a Spitfire bucketing down out of a blazing June sky, cannon blazing).

The Passing Out Parade climaxed our basic training. I stood on the parade ground with the entire intake. The officer in charge of the Parade chose me as Lead Man. The officer was from another Wing, so didn’t know me, didn’t know I hadn’t done drill. I didn’t think to tell him.

At the word of command I set off, and the Parade followed me.

In everyday life I had a tendency to veer from the straight when walking. This was normally of little consequence, but on the vast space of the parade ground, without boundaries or landmarks, I began to steer sharply to the right. The phalanx of columns of marching men perforce came with me. The phalanx marched at a lick towards the spectators: the officers and their wives lining the edge of the parade ground, until the young man to my left hissed urgently ‘For God’s sake Leo,’ and alerted, I swung abruptly to the left, the Parade following, marching parallel to the spectators, and no more than three feet from them.

At the extreme edge of my field of vision, behind the frozen watching faces, I could see the face of the padre, grinning.

Early in April 1949 the intake moved to Credenhill for technical training. I was intended for clerical training, but did none: diverted instead to a Squadron office that produced graphics material.

I made sure to attend the typing classes, though. Touch-typing was a valuable resource, and I meant to have it.

The lessons were to music, a room full of young men and women recruits obediently following the music, plink plonk tiddly plonk, plink plonk. I couldn’t be bothered with that, though, and went racing ahead.

The typing instructor stopped behind me: “You never follow the music, do you Baxendale?”

“No, corporal.”

He sighed, without rancour, and moved on.

In June 1949 the intake was broken up and scattered to units across the country.

I made my way to RAF Yeadon north of Leeds and Bradford.

I was a Clerk, General Duties, Aircraftsman Second Class. At Yeadon I was made Clerk to the Catering Officer. After a while he went on an Advanced Catering Course and never returned, so that I was left in charge of catering for the camp of 120 officers and men.

I was thirteen months at Yeadon. For the last ten months, my money was spent on drawing materials, my time spent on preparing a portfolio of work: book jacket designs, book illustrations, strip cartoons.

At the end of June 1950 the Korean war began. National Service was extended from eighteen months to two years. The extension missed me. I was discharged. Those due for release a fortnight later had to serve a galling extra six months.

A Wing Commander arrived post-haste from HQ: I had overspent the catering budget by £2,000. He told me that if I had been an officer, I would have been court-martialled; but that I was an AC2 doing a Warrant Officer’s job. There was nothing to be done.

I left the camp on 29th July 1950 to catch the bus from Yeadon to the railway station at Leeds. I carried with me the heavy portfolio of thirty pieces of work, each of half-imperial size, three for each of the past ten months.

The editor of the Lancashire Evening Post, Frank Wilford, looked at my portfolio, and offered me a six months’ trial. I would be on the editorial staff. All the departments of the paper, News, Sport, Advertising, Women’s Section, could call on me for cartoons and illustrations; but I would be answerable directly to the Editor. I could start on Monday.

PÓM: Did you ever have any formal training in art?

LB: The only ‘formal training’ I had that mattered to me, was given with unstinting generosity and courtesy by the senior English master James Lawson, who was ill, with a deformed back, and died young. I loved the language, to understand it, and to know its structures. I felt then, and feel now, gratitude to James Lawson, for his generous teaching, and for his courtesy.

A week after I left the Catholic College, my mother’s sister Monica went to see the headmaster about her son. In the course of the meeting, Father Duggan, who had taken over from Father Malone at Easter, told her I should have gone to Oxford. The message was passed on to me without comment.

I had spoken to Father Duggan several times in the weeks before I left, but he had said nothing to me about Oxford. Though I had never told him (or anyone) why I was leaving at the end of the Fifth Form, I imagine he knew the score.

Since the things I didn’t do go on to infinity, I will here rejoin the narrative of what I did do.

From a flying start at the Lancashire Evening Post, I found myself constantly on the move, drawing quickly, then running up and down flights of stairs, taking drawings to the sports editor, to the process department, to this place and that; and at the weekday evenings, at home, writing and illustrating articles, drawing pocket cartoons and strip cartoons, whatever came into my head for the paper; and each Saturday travelling to football, rugby league, rugby union, golf, cricket, according to season, then on Sundays drawing the resulting four-column cartoon features for the Monday sports pages.

Something bothered me, though. It was always on my mind. I drew under the influence of Heath Robinson and Rowland Emett; but I couldn’t carry on doing derivative work; how could I find out how to make work that sprang from me freshly minted?

Then something happened.

There was a capacity crowd for a rugby league cup tie at Wigan. There was a capacity crowd of reporters in the press box too, but I managed to squeeze in with my sketch pad.

As the crowd roared, I was seized by boredom. My mind began to drift about absently, and make its own reality: I wandered onto the pitch with my sketch pad, to find myself being scooped up by towering players to score a try, then booted over the bar. And so on.

The whistle blew, the crowd roared, I surfaced from my reverie, and asked the reporter next to me for the final score. Then I went home to draw it all for the Monday sports editions.

This was a staging post in my life. I realised now, that all I had to do was to cast my mind adrift from its moorings, and ideas would come.

That staging post of realisation led to others in turn.

The Lancashire Evening Post was a broadsheet, with its front page like the nationals, full of news and maps of the ebb and flow of the Korean war.

The large broadsheet pages could take a lot of both editorial and advertising drawings, and I drew them all as need arose. Some of the adverts had to be drawn straight, but seeing that the advertising department had a persuasive salesman in Joe Whitacker, I put him up to persuading the clients to agree to cartoon adverts, and they did.

Thus it came about that I drew a series of half-page ads for a local charabanc tours firm: a coachload of tourists plunging down a ten thousand foot drop, and suchlike enticements.

Here is curiosity. On 8th December 1952, I had my first meeting with DC Thomson managing editor RD Low, and Beano editor George Moonie. We went through a bundle of cuttings of my drawings for the Post (of which I had about a thousand – this was a judicious selection). RD Low pointed to the half-page advert of a coachload of tourists plunging down a ten thousand foot drop: “We like this kind of robust humour.”

And yet that wasn’t what they asked me to do. I told them I had felt a jolt of excitement at seeing the new Dennis the Menace in The Beano, that this kind of work must be the future, and that’s why I had approached them; but the two men brushed all this aside.

George Moonie had brought an idea with him: Chopstick Charlie Choo the Chinese Detective. I kept my face inscrutable, but my spirits dropped. Charlie Choo was obviously derived from the 1930s Charlie Chan movies.

This began an intense struggle over what I should create for The Beano – or if I was to create anything for it at all.

PÓM: In the various places that you mention your father, you often describe him as being angry about a lot of things. Was he a difficult man to live with, and how did all this anger affect you?

LB: I have set out in this interview to answer structurally, in the knowledge that we live in a control system which habitually presents what is structural as personal.

The use of language is at the heart of the matter. I believe that anger is a protective faculty, against harm.

The working class was constructed by baleful power. My mother and father, like others of their class, were torn from school at the age of twelve, to work ‘part time’ in the mills. That phrase ‘part time’ is a mockery of language, ‘part time’ being six hours working at the mill each day before the rest of the day at school, then full time work at thirteen.

There were few enough school years to waste, and my father had the bitter taste of “playing with clay.” He understood what was done to him, and what it meant for his life, and for his children.

The stealing of the wherewithal from my parents, meant that though they understood with clear vision what was done to them, there were matters of the mind, of understanding, that were closed off from them. They, like numberless others, were made to be afraid of difference, of what was strange to them.

In 1944 there were shows on the wireless like Happidrome: [comedian] Harry Korris playing the variety theatre manager Mr. Lovejoy, Cecil Frederick as stage manager Ramsbottom, and Robbie Vincent playing the gormless callboy Enoch. This was expertly delivered traditional comedy, and we, my father and I and the family, listened and laughed together.

But I described in my sixth answer, how when Max Wall came on, he at once unsettled my father, who reached over to switch him off. But I also described how 34 years on, in May 1978, when Ian Dury gave his first major concert at the Hammersmith Odeon, the audience of punks were unsettled like my father by Max Wall, and were loud in derision, trying to switch Max Wall off, until Ian Dury stormed on and told them to shut up and listen.

Ian Dury was angrily dealing with a disturbance in the minds of his audience caused by difference, by what did not conform, a fear of difference that had been cynically manufactured.

My father died at 68; and his mind and body had been smashed long before that.

My mother, looking back in old age, told me: “Lack of money distorted everything; it distorted the thinking” and she told how my father, released briefly from the burden of work, became a different man: on a day trip to Windermere with the youngest of my siblings, other passengers told my parents they were on the wrong train, it was going to Penrith, but my father laughed out loud: “I don’t care where we end up so long as we have enough sandwiches.”

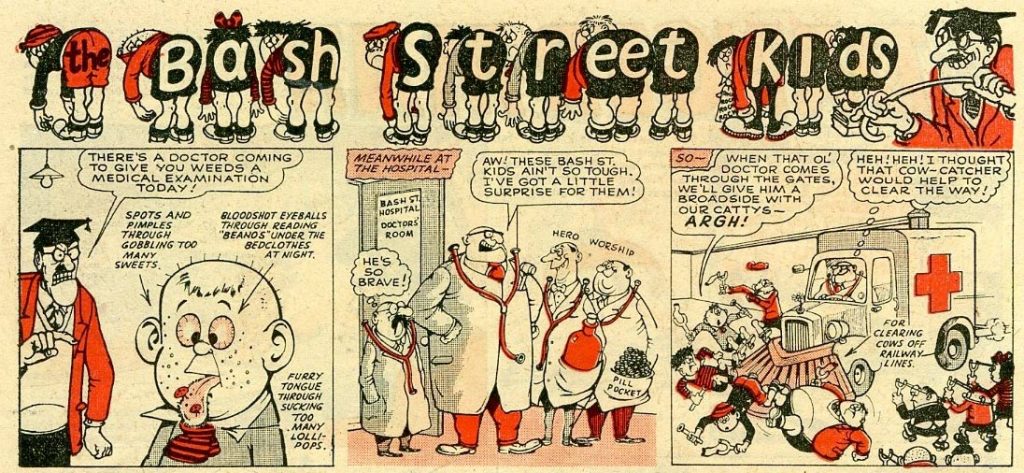

Art from “The Bash Street Kids” by Leo, one of the great, long-running strips of the Beano, published by and © DC Thomson

PÓM: What did you submit to The Beano, after that meeting?

LB: I was stuck with Charlie Choo, thinking, thinking, thinking what to do?

Of the 30 drawings I had made in the RAF, one had been the first three pages of a book, in comic strip format: pen and ink and monochrome wash on fashion board; the adventures of a crowd of children, in underground caverns.

Now, in extremis, I thought of that tumult of child characters again; but no matter what I did, I couldn’t figure out how to fit them into a Beano scenario.

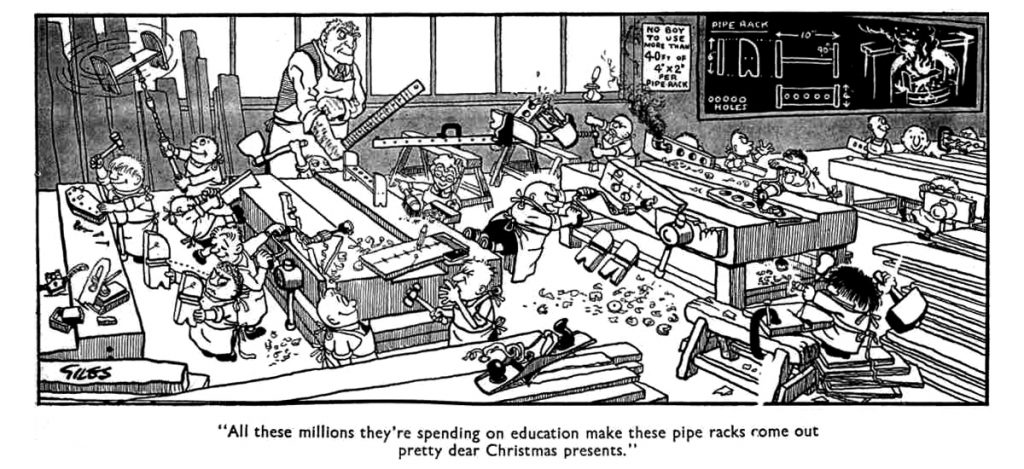

Inspirational: Leo Baxendale acknowledges a debt to the work of Daily Express cartoonist Giles for securing work at The Beano. This cartoon, published 2nd December 1955, is typical of Giles school-inspired cartoons

Five weeks on from that meeting, on the morning of 13th January 1953, I opened my parents’ Daily Express and saw a Giles cartoon of a pandemonium of pummelling, thumping children, the odd head flying off, as they poured out of school. It was a smaller Giles drawing than usual, no more, relatively, than a vignette, but I was taken by excitement at it.

I pencilled a large scene, a bison herd of kids stampeding out of school, their marmalising hooves trampling the world underfoot: “The Kids of Bash Street School“, and posted it to RD Low.

I waited with expectation, but his response was unexcited, offhand, a dampener. I was still stuck with Charlie Choo.

March came in on the lam, with doldrum drawings of Charlie Choo done to keep the payment cheques coming, while my pinwheeling brain threw off ideas for new characters, but none of them would do.

Early in April I sat in the living room, thinking, and wondering. My brother Richard came in with a couple of comics – a newly bought Beano, and a swap. When he had finished with the Beano I picked it up: “Dennis the Menace” was by now a full page, and had taken wing. This was what had made me approach The Beano in the first place; this was what I ought to be doing. But I couldn’t just replicate Dennis. How to create another Dennis – yet different?

I happened to look up and glance across the room at my brother. Richard was reading his swap, holding it folded back. On the page facing me, I saw an illustration of Hiawatha.

Eureka! I would synthesise Dennis with Hiawatha.

I pencilled in the character, chubby, bare to the midriff, with a bellybutton, and Davey Law’s stylised Dennis the Menace mouth. I posted it to George Moonie, and waited in continuous excitement for his reply.

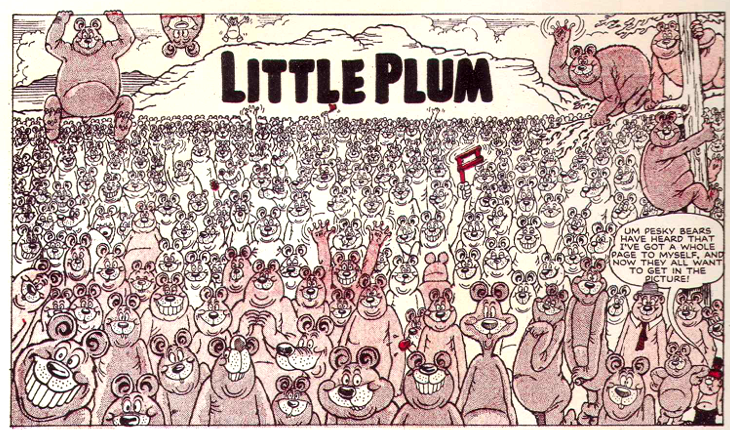

“Little Plum” for The Beano Issue 880, by Leo Baxendale

14th April: George responded swiftly, and I set to work on the strips. In my mind was the intent to create a being who lived in a world of thirsty deserts and hungry vultures (knives and forks at the ready), stampeding bison with marmalizing hooves, ten-thousand-foot-drops, and much else; but a large part of that vast world of comedy would be carried in our hero’s own little noddle.

But I found that the first strips I drew weren’t coming right, and I had to stop and work out why. To convey that the little chump was by turns cowardly, naïve, credulous, a gormless conniver and a disaster-prone bumbler, an infinitely malleable set of facial features was necessary. I realised the Dennis stylised mouth was a hindrance to that. I discarded the Dennis mouth, and we were away.

When the feature appeared in The Beano, it was titled “Little Plum Our Redskin Chum”, a rhyming couplet. (Curious about the pervasive rhyming couplets in The Beano, I delved about and found they were part of a tradition going back to the Middle Scots of Gavin Douglas and David Lindsay in the 15th and 16th Centuries).

By the end of August: twenty or so “Little Plum” sets stockpiled.

3rd September: a letter from George Moonie asking for a strip with a girl character, The Minx.

George asked me to send several portrait sketches of The Minx, so that he could choose one.

I couldn’t be bothered with that, and impatient to be off, thought up and pencilled the first strip and sent it to Dundee by return of post.

George too responded by return, sending the drawing back to me for inking; we were gathering speed.

I made Minnie the Minx a girl of boundless ambition, in constant physical and psychological struggle against those who would hold her back: armies of boys, headmasters and careers officers, and her own father. In creating Minnie, I gave her intensity of will.

Minnie the Minx art by Leo Baxendale from The Beano 852, cover dated 15th November 1958

16th October. A letter from George: ‘I shall be in Preston next Tuesday, 20th October, emerging from the Perth train around 2.51pm. Can you meet me at the station?’

The letter didn’t say why George was coming.

George Moonie emerged from the Perth train around 2.51pm. I met him at the station.

Over a pot of tea in the Kardomah café, George asked me: would I create a third feature, a two-thirds page set, featuring a crowd of children pouring out of school?

I told George in a daze of excitement that this was exactly what I had longed to do: what had made him think of it? George looked surprised and shuffled through the papers in his brief case. He pulled out the pencil sketch of “The Kids of Bash Street School” that I had sent to RD Low in January: “This gave us the idea. You sent it to us. Don’t you remember?”

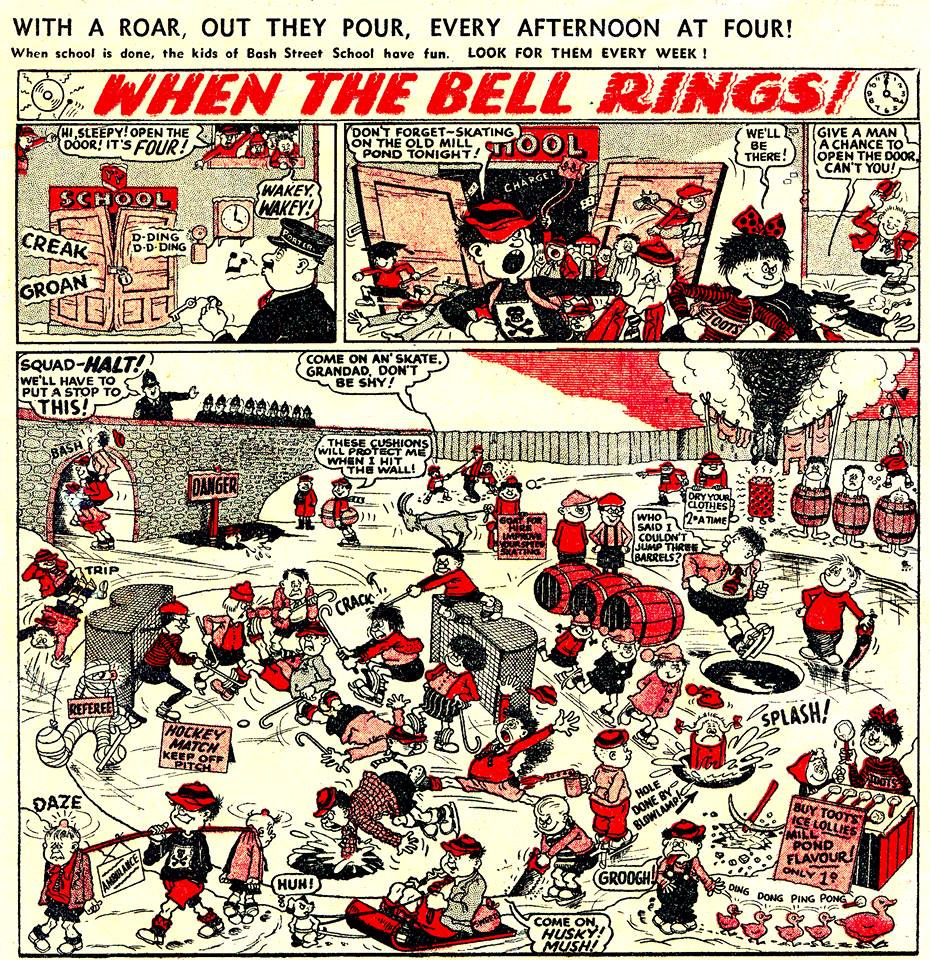

(Leo’s When the Bell Rings in the immortal Beano, which would become the Bash Street Kids, entertaining, and hopefully corrupting, young minds for generations since)

As I began the long straight walk along the length of Fishergate I had already begun the working out in my mind of the first Bash Street production set. George had asked for a winter scene, since he meant to launch the feature soon after Christmas. That meant snow and ice.

As I strode, I quickly decided on a frozen pond setting, that would provide both a common theme for gags, and a closely bounded composition where I could place all the characters either in the foreground or middle distance.

The first ‘proper’ episode of “When The Bell Rings” from The Beano No. 604. Issues 602 and 603 had teasers in them, sharing the page with “Minnie the Minx”.

By the time I reached the other end of Fishergate and my bus home, I had worked out most of the gags and comic sequences (but not created the individual characters – that would come in the act of drawing).

Arriving home, I set to on the drawing at once, working on the dining room table.

When the time came for my mother to lay the table, I had to clear my drawing away for the family tea, impatient for the meal to be finished, so that I could take over the table again.

When it was time for bed, and I had to break off from the drawing of that first Bash Street, I was eager for the morning.

This interview was carried out between April and July 2012, and was originally supposed to accompany a 60th anniversary exhibition of Leo’s Beano creations towards the end of 2013, which never actually came to pass. For that and other reasons the interview was shelved, but I’m very glad that it is now seeing the light of day. It was to have been, more or less, an introduction to the exhibition, and is some way one is not complete without the other, but we thought we’d like to share it now, on this, his birthday, as a reminder of one of comics’ great wizards, and the times and life that shaped his views and work – Joe Gordon

Pádraig Ó Méalóid has a long history of promoting good comics and science fiction works, from organising conventions in his native Ireland to extensive writings and interviews with creators such as Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, Kevin O’Neill and more. He is the author of Poisoned Chalice: The Extremely Long and Incredibly Complex Story of Marvelman (and Miracleman) and Mud and Starlight: The Alan Moore Interviews 2008 — 2016

Leo Baxendale, cartoonist, born 27 October 1930; died 25 April 2017. Leo is survived by his widow Peggy; children Martin, Carol, Stephen, Heather and Mark; grandchildren Rosie, Jacob, Zuza, Jo, Misho, Eloise, Joel, Jake, Owen, Tamsin; great grandchildren Rupert, Barney and Zoe

WEB LINKS

• Leo Baxendale’s official website is here: www.reaper.co.uk

• In Memoriam: Leo Baxendale – a tribute by John Freeman for downthetubes

This tribute include numerous links to interviews and other features about Leo’s life and work

———————————————————————————————–

AN AFTERWORD BY LEO BAXENDALE

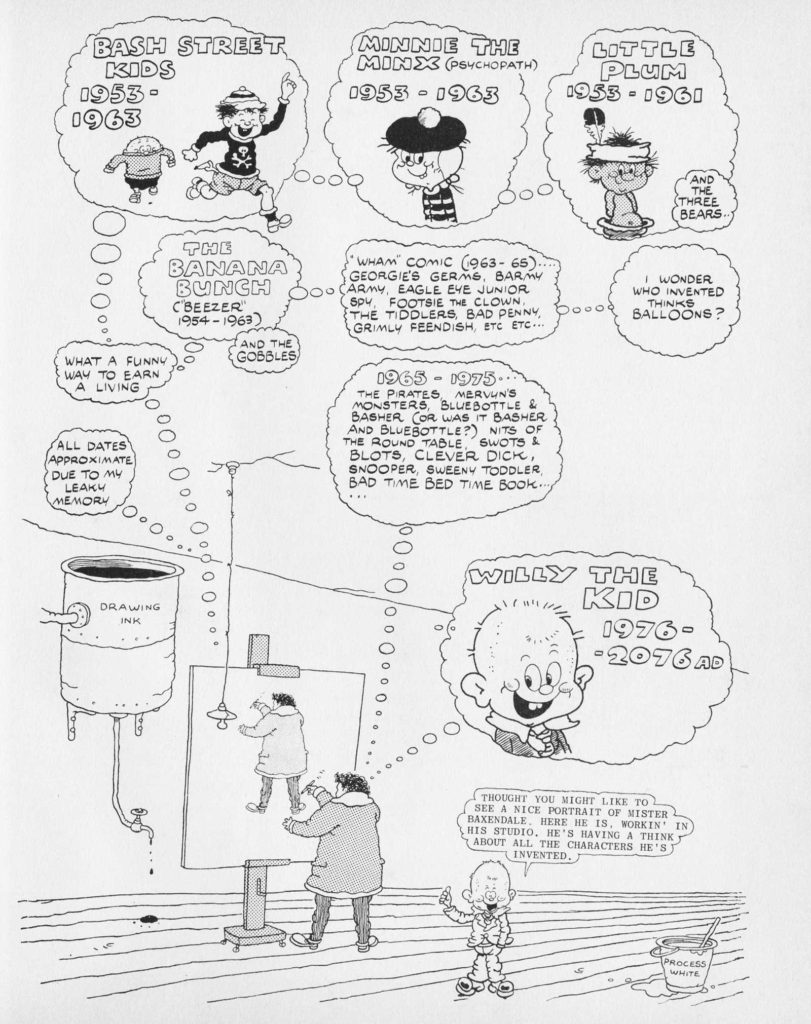

Leo Baxendale’s self portrait

I am glad, more than I can say, that Forbidden Planet have provided the stage and switched on the footlights to enable these words to dance attendance on the sixtieth anniversary of my creations for The Beano. This is to acknowledge that generosity of spirit.

It has been my observation, it is my belief, that every child, man child and woman child, is born with the faculties of learning and synthesis, that together make creativity possible.

Whether those inborn capacities are translated into professional capability is dependent on circumstance. Circumstance, more often than not, will be determined by the controlling system in which we live.

The structured oppression of women and its concomitant invention of slavery, leading to patriarchal class systems, was constructed in the last 3,500 years, in Mesopotamia; with the contagion spreading from there to take over the world.

The inventing and development of such an intricate oppressive system demanded the writing of it all down, in myriad laws and regulations.

It is fortunate for history that all these myriad writings were done by the scribes on clay tablets, and could thus survive. Their survival means understanding, and understanding brings a structural means to resist.

That system in its turn was to make possible and lead finally to the deadly virus of capitalism.

In the scale of history, 3,500 years is a relatively short span. It hasn’t taken long to bring us where we find ourselves today, in the endgame.

That controlling system has conjured away the wonderful intricacy of creativity, and by sleight of mind replaced it with the notion that artists are born with a special ‘gift’, a rackety construct with the high priests forever having quick-drying concrete shovelled around its foundations.

I moved to Scotland on the 30th of November 1953, renting a flat at Broughty Ferry by the Tay estuary where I lived and worked, a ten minute tram ride to the Beano room in Dundee.

George Moonie told me that the two million copies of The Beano sold each week had a readership of half boys and half girls, with the main group of readers aged nine to thirteen. There were other smaller age groups, and numbers of adult readers.

Each time that I took a drawing to the Beano room, I made sure to look at the readers’ letters.

I was struck by the drawings that decorated the letters. Though the readers were decorating the margins with my creations (or those of Davey Law and Ken Reid) the individual styles of their drawings were markedly different each from the other.

Once the imagination of a child is set alight, it takes persistent dousing with cold water to put out the fire.

Leo Baxendale

[amazon_link asins=’1781087261,086166051X,B002CI7EY8,0715610902,B00114LNB4,0715613111′ template=’ProductCarousel’ store=’downthetubes’ marketplace=’UK’ link_id=’d2836014-5c60-4281-b49b-48ac57297263′]

The Beano, Bash Street Kids, Little Plum and Minnie the Minx © Beano Studios

Boy’s Own Paper and Champion and “Rockfist Rogan” © Rebellion Publishing Ltd

Joe has been a bookseller since the early 1990s, with a special love for comics, graphic novels and science fiction. He has written for The Alien Online, created & edited the Forbidden Planet Blog and chaired numerous events for the Edinburgh International Book Festival. He’s more or less house-trained.

Categories: Creating Comics, downthetubes Comics News, downthetubes News, Features

The SEQUENT’ULL Interviews: Dan White

The SEQUENT’ULL Interviews: Dan White  The SEQUENT’ULL Interviews: Michelle Freeman

The SEQUENT’ULL Interviews: Michelle Freeman  The SEQUENT’ULL Interviews: Colossive Press

The SEQUENT’ULL Interviews: Colossive Press  The SEQUENT’ULL Interviews: Comic Creator Mark Stafford

The SEQUENT’ULL Interviews: Comic Creator Mark Stafford