Gamish: a Graphic History of Gaming

Edward Ross

Particular Books

Review by Joe Gordon

I first encountered Edinburgh-based comicker Edward Ross’s work in one of my second homes in the city, The Filmhouse, a local arthouse and Indy cinema that is also home to the Edinburgh International Film Festival (the oldest continually running film festival on the planet). Back then, Ed was producing his Filmish comics, in the finest tradition of the home-made, small press scene, complete with staples holding them together, and on sale in the Filmhouse box office. I picked up each of them as they came out and reviewed them on the old Forbidden Planet Blog, then in 2015 SelfMadeHero published a large, expanded and re-drawn version of Filmish, greatly improving on the original mini-comics to give a longer, more in-depth look at the history of cinema and film and its place in our culture – not just the technical and artistic innovations across a century and more, but also how some films reflect the culture of their days, their preoccupations, worries, fantasies, fear, prejudices (race, class, gender and more).

It made for fascinating reading. When I interviewed him at the 2016 Edinburgh International Book Festival about Filmish, I asked Edward what he planned to follow it, and Ed replied that he was considering a similar approach to video games. And as we continue to stumble through 2020’s stormy seas, grabbing at good comics and books like lifeboats to help keep our spirits afloat (or simply to transport us away from the actual world for a while), Gamish arrives, and yes, before you ask, I think it was very much worth the wait.

Gamish is very similar in format to Filmish, both in physical appearance (a smaller 235 by 170mm format instead of the larger “comic album” format, although in hardback this time) and layout, but also in approach, not least in the use of a virtual Edward inserted into the events as a guide to what is happening..

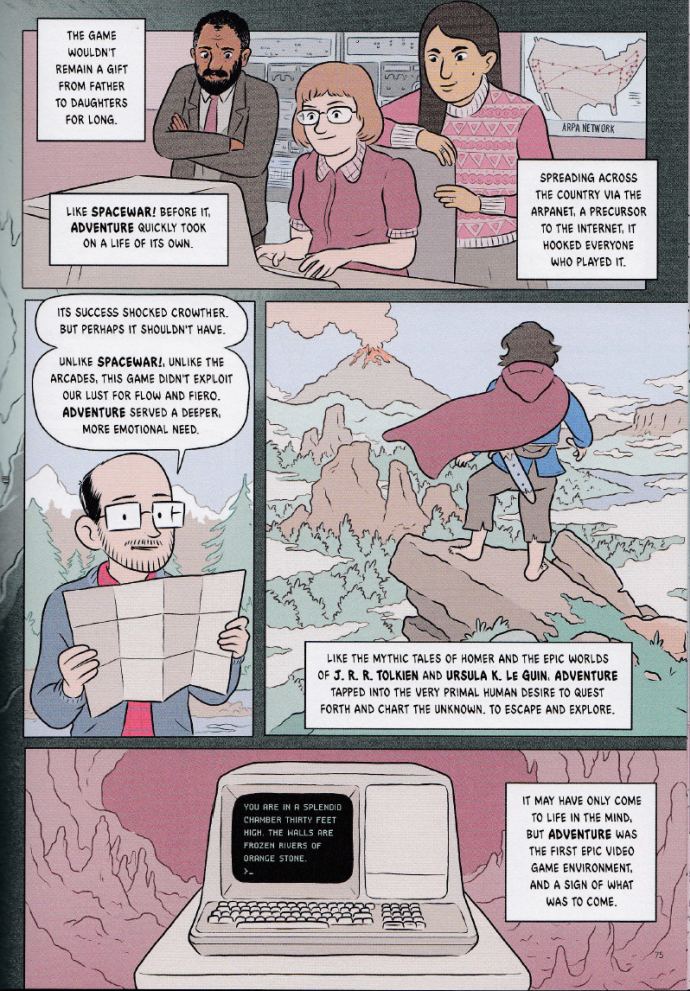

Filmish tackled the century and a bit of film history by taking themes for chapters, such as technology, and Gamish also has a number of themes to help explore the history and the culture of gaming, from the role of technological innovation and artistic interpretation to the portrayal of race and gender, of disabilities, of cultural norms (and blind spots) both in the games and within gaming communities too. And like the earlier Filmish, Ed has undertaken an enormous amount of research to try and place all of this within a historical context – this doesn’t just take a simplistic approach to video game history and evolution, Gamish also explores why human beings play, how that play has become more elaborate as humans moved from hunter-gatherer to early civilisations, and placed the modern video games within that millennia-long history of human culture.

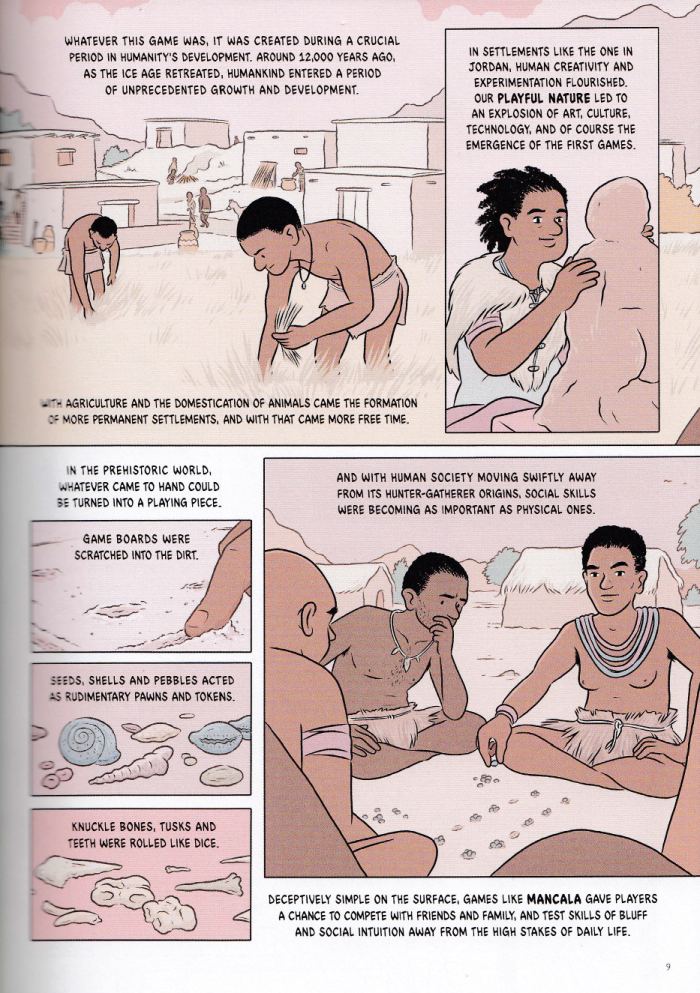

Early in the book, Ed asks why it is we play: in fact, as he notes, most animals, especially mammals, play, be it kittens pretending to hunt a piece of string or human children making up games to play in the park or with their Lego and action figures. Play is part of how animals, including humans, learn important skills for later life, of how to be and how to act and how to perform certain acts, but it is also often a bonding and socialising tool as well, teaching us how to interact with others (also helping us form relationships as well as skills), and, of course, it is often hugely pleasurable. Ed takes us to an excavation near Amma, where a new roadworks dug up a 9,000 year old village site. Within this the archaeologists discovered a stone board with rows of indentations, which some recognised as a gaming board. In fact it strongly resembled a version of Mancala, a family of similar games which were widely played around the Middle East and Mediterranean basin back in Antiquity, and is still played to this day, especially in parts of Africa.

Just as ancient cave art such as those in Lascaux, France, or the Aboriginal rock paintings on the Burrup Peninsula in Australia reminds us that our ancestors of thousands – even tens of thousands – of years ago were not some simple “ugh, ugh” brutish, apish people but modern homo sapiens like us, the same bodies, the same brains, the same desire for self expression and abstract thought and creation. And gaming. A few indents in a piece of stone, pavement slab or wooden board, nearby pebbles for playing pieces and human imagination, and we have games we can play with others. As Gamish makes clear, this is not something unique to modernity, or even the great civilisations of the Classical period, this is quite simply a facet of being human, and the first part of the book takes us from those prehistoric games to the slow evolution of more sophisticated games like Go and Chess, which travel around our world and different cultures, being played for pleasure but also as training for the mind in organisation, even in military strategy (think of Chess as battlefield command training).

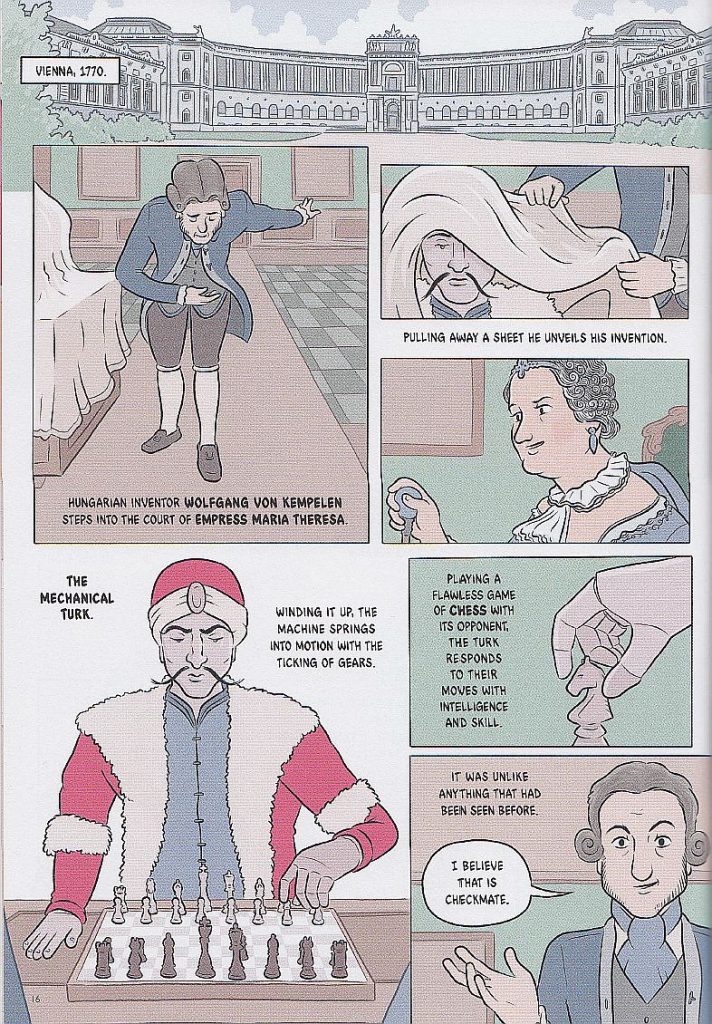

In this early chapter we first get a glimpse of the technological games that are to come, and which will take the majority of the focus of the rest of the book: enter Wolfgang Von Kempelen with his astonishing Mechanical Turk, a robotic chess player that challenges humans across Europe then later the Americas, this automaton playing against such figures as Napoleon and Benjamin Franklin. As many of you will know, after more than a century of touring the globe with great success, the Turk was eventually found to be a fraud: it was not a machine intelligence, but a masterful chess player concealed cleverly inside the mechanism, working the Turk’s arm through pulleys and levers (if you are interested, Tom Standage did a terrific book on the Turk back in 2001 that I highly recommend).

So this proved not to be the start of us using clever machines for gaming – but it did inspire much of what came later. Not just in the way Alan Turing (also featured here) used chess as a way to test and try computer learning in the mid-20th century, or the numerous programmers who tackled chess as a way of improving computer learning (eventually leading to Deep Blue beating human grandmaster Kasparov), the very idea of a machine capable of the intricacies of a game like chess, with so many possible outcomes (increasing with each player’s moves) inspired the likes of Babbage, along with Ada Lovelace one of the father’s of what would evolve into modern computing, and computer chess remains a challenge tackled by many programmers and engineers from Turing to today, both in fact and in fiction (consider HAL playing his human crew-mates on the Discovery in 2001).

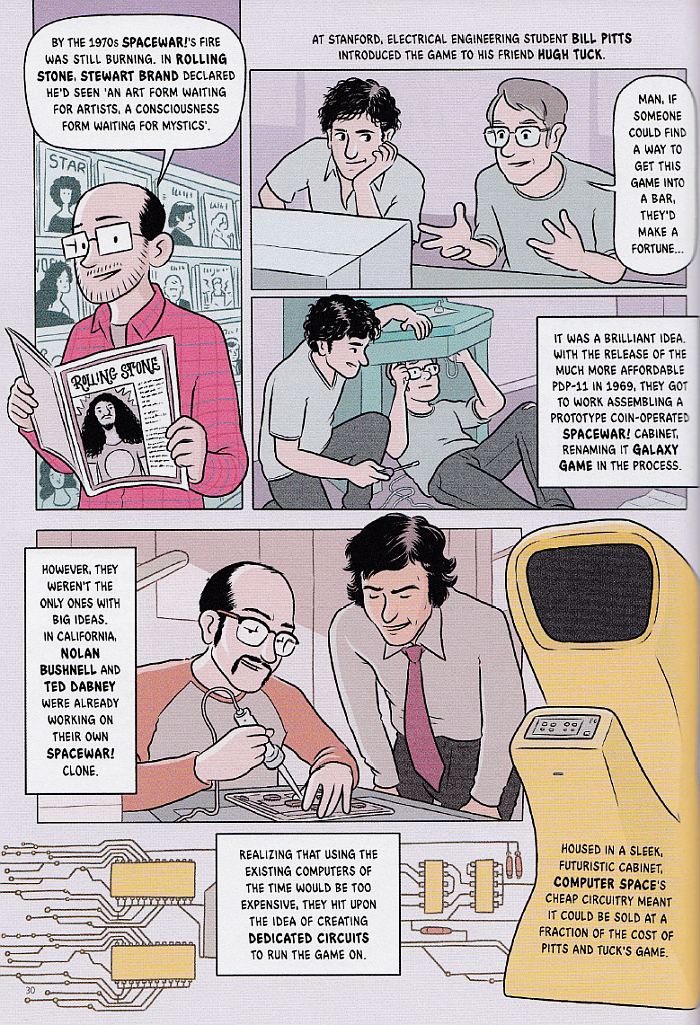

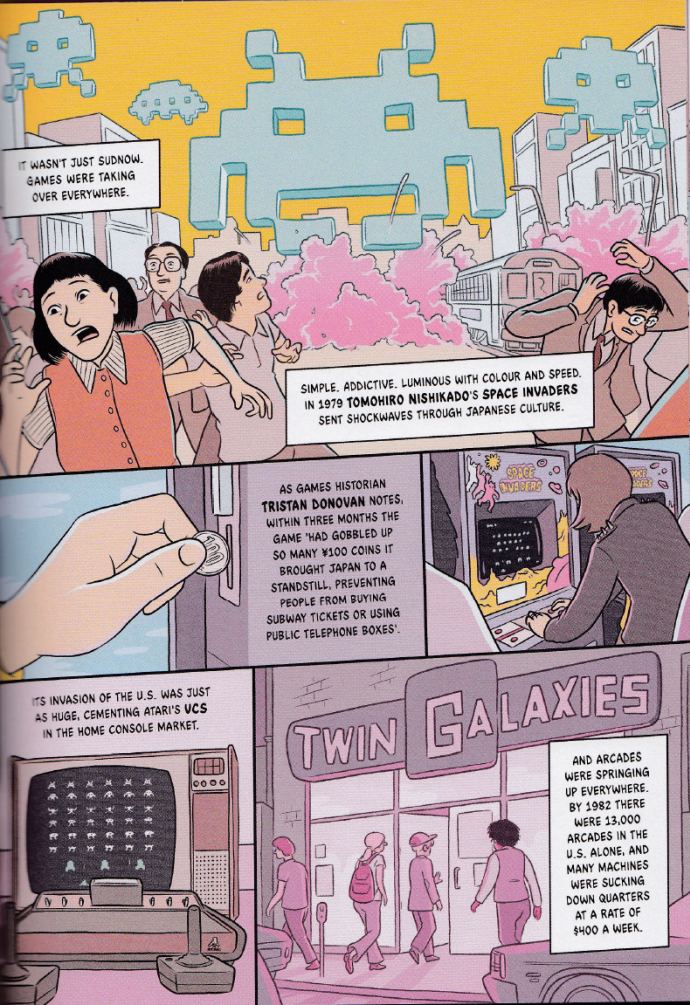

All of this is fascinating in its own right, and Ed continues to chart the evolution of computer gaming into forms contemporary readers would recognise – heck, some of us even played early versions of these, such as the now iconic Space War (I remember playing a version of this tweaked for amusement arcades in the late 1970s and early 80s and loving it), the move from students using room-sized University computers to run games after hours to the first home games and the birth of what is now a multi-billion dollar industry with simple games video games plugged into the TV in your living room, from Pong to the cartridge-based Atari, the explosion of video arcade culture (at one point in the early 1980s so popular that in Japan it lead to a national shortage of coins as they were all being rattled into Space Invaders and other games cabinets in the arcades!), and the evolution through those early, simple 8-bit games to today’s hyper-real, fast-paced, detailed graphics and richly visualised alternate realities, from text based dungeons and dragons games to massive, multi-player online fantasy worlds accessed from around the globe.

All of this is interesting in its own right, however what makes Gamish, as with Filmish, at least for me, is that Ed is at great pains to put the human dimension into this history. This isn’t just a straight, chronological history of technical development leading to bigger, better, more sophisticated games and virtual realities. As with Filmish, Ed is interested not just with how we increase the sophistication of our computers, programmes and gaming, but also the how and the why, and also how these have shown up many of our inbuilt social norms and prejudices, as well as how they can be used to tear those down. He looks at how many games for far too long offered only character avatars to the player who were male and white, or, as in World of Warcraft, we get non-human characters representing different cultures but which mostly draw on a very blinkered, European notion of what Native American or Asian cultures are.

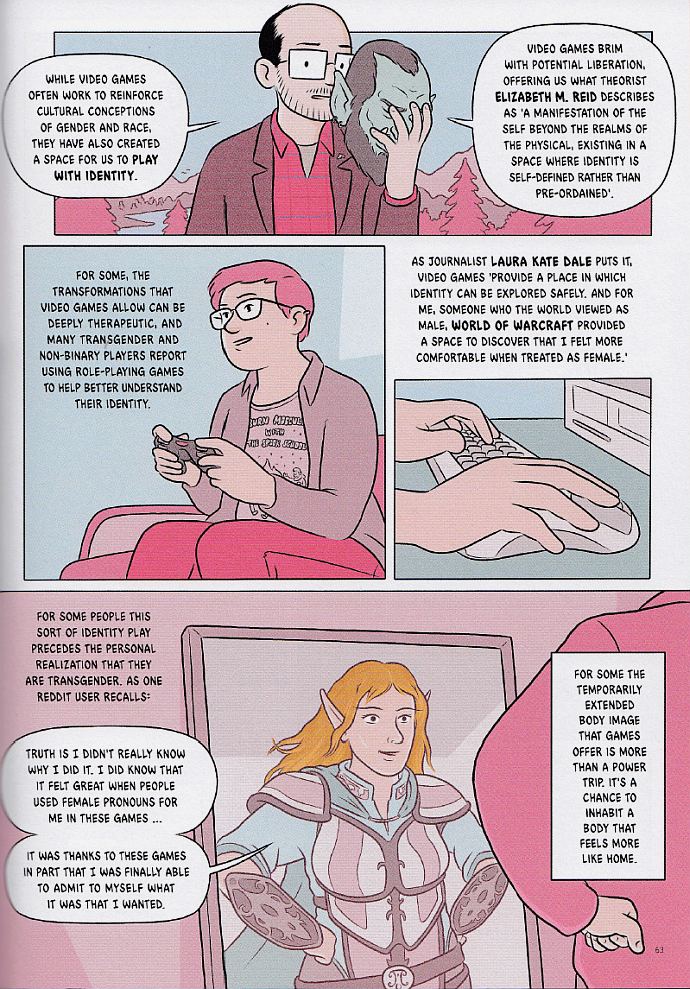

Gender and sexual identity, as well as ablism are also covered here – he notes how in the increasingly complex gaming worlds your on-screen character could follow multiple paths, even have romances with other characters, but usually those relationships were purely heterosexual. Despite modern games offering multiple options to players to navigate their character’s paths, it hadn’t occurred to the programmers to offer the choice of sexually different tastes, just as many hadn’t thought to include player avatars who had skin other than white, or more female options. Ed also touches on the hostility of a wretched (and thankfully small) section of the emerging gaming community, mostly young, white males, who became so possessive over games as belonging exclusively to them that they attacked female, LGBT or players of different skin colours on forums and in gaming worlds (sadly, as with GamerGate, we’ve seen a similar bunch of utter idiots in the comics world too with very much the same notions).

However Ed also covers the more positive aspects of this gender, race and cultural disparity in gaming, bringing forth all sorts of examples where different groups have used the medium to empower themselves, be it refugees creating an idealised homeland they can dream of in cyberspace to transgender and non-binary players who found being able to inhabit any form of virtual avatar was therapeutic for them, and helped them explore their true inner identity in virtuality before making decisions and lifestyle changes in the real world, or Muriel Tramis creating a game where you had to play as a rebelling plantation slave as a way to highlight that dreadful period of history (and by implication its continuing influences to this very day in terms of how some people are perceived and treated even in supposedly free and equal societies).

Naturally this book also touches on that old bugbear of video violence and its possible effect on people in the real world. As Gamish points out, yes, there certainly has been a growth, especially in the 1990s, of very graphically violent video games, not least the FPS or First Person Shooter, made famous by the original Doom (which I must admit I loved playing on my early PC, an hour of that would be my unwinding after spending hours on the same machine writing my college essays), and how an often rather lazy connection was made between these and real world violence (especially the dreadful problem of school shootings in the US). As the book notes though, while there should be some concerns, this moral panic was just the latest in a long saga of blaming different new media for societal ills – in the 1950s it was rock music records, in the 1980s it was “video nasties” and rap music, in the 1990s it was video games. It’s always easier to simply blame those than actually try to understand where families and societies are going wrong to produce those real world problems (it also, as Ed observes, ignores the fact that if the games were indeed the cause of this real world violence then we would be drowning in such acts as millions plays them every single day).

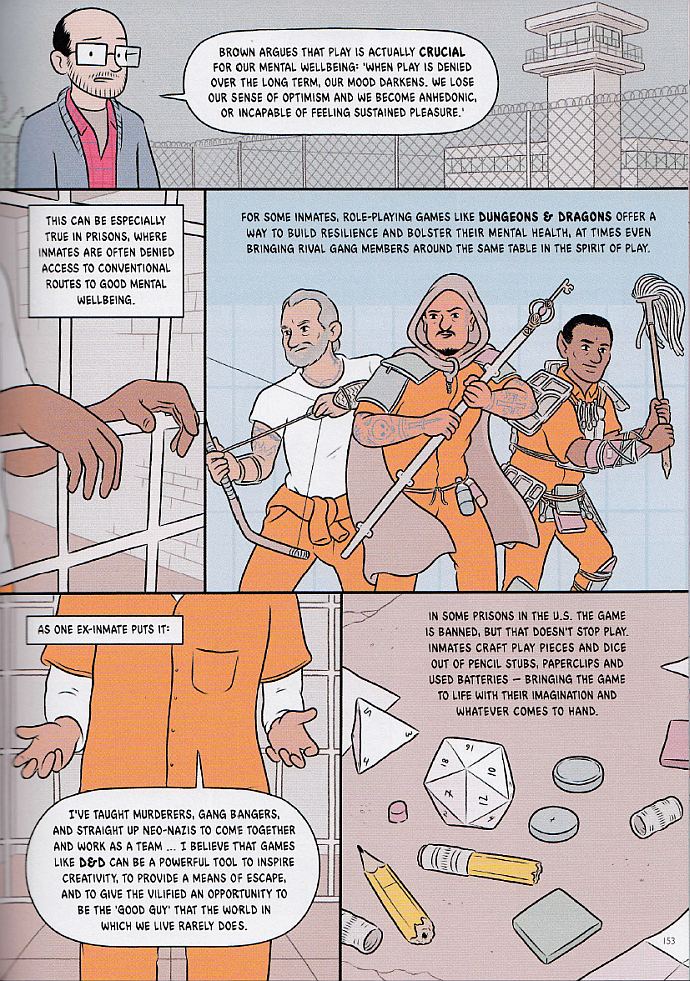

Overall however, while Ed does explore the negative side of gaming culture, the tone here is bright and optimistically hopeful – while he details faults like sexism or ablism or cultural difference ignorance, he prefers to give far more space to positive stories, of individuals and groups who have challenged norms and used technology and gaming advances to their own advantage, to claim some of that virtual, shared cyberspace play realm for themselves, but also to share it with others and so educate us to new ideas and people and ways of being. And frankly, I am glad he takes this approach – he’s far from ignoring the many problems, in fact he discusses them, but he chooses to highlight positive aspects of gaming and the power within games to help us make things better by building more understanding through shared activities, learning, creating new friendships with different people with different views on life.

Much as he did in the earliest pages of the book, when talking about our hunter-gatherer ancestors and their early play models that helped them learn skills and socialisation, Ed’s later chapters explore examples of how many today are using the modern, sophisticated gaming environments available to us right in our own homes to do the very same, with different sorts of people all over the world. It’s warm, it has a sense of fun and humour and importantly it has a lot of optimism for the media and for the way it can empower all sorts of people (the book takes pains to include a lot of diversity in the characters we see, which again I appreciated greatly), and right now that feels like a wonderful, uplifting notion to leave the readers on.

Joe Gordon

• Gamish: a Graphic History of Gaming is available now from all good book shops and from AmazonUK here (Affiliate Link)

• More books by Edward Ross on AmazonUK (Affiliate Link)

• Check out the dedicated Gamish web site at gamish.co.uk

• For updates and news about Edward Ross’ many projects, follow him on Twitter or like Filmish on Facebook

Joe has been a bookseller since the early 1990s, with a special love for comics, graphic novels and science fiction. He has written for The Alien Online, created & edited the Forbidden Planet Blog and chaired numerous events for the Edinburgh International Book Festival. He’s more or less house-trained.

Categories: Reviews

In Review: The Leopard from Lime Street – Birthright

In Review: The Leopard from Lime Street – Birthright  In Review: Twisters

In Review: Twisters  In Review: The Beast-God

In Review: The Beast-God  In Review: “3 Stories featuring An Egg, A Saint, and Border Guards” by Edward Taylor

In Review: “3 Stories featuring An Egg, A Saint, and Border Guards” by Edward Taylor