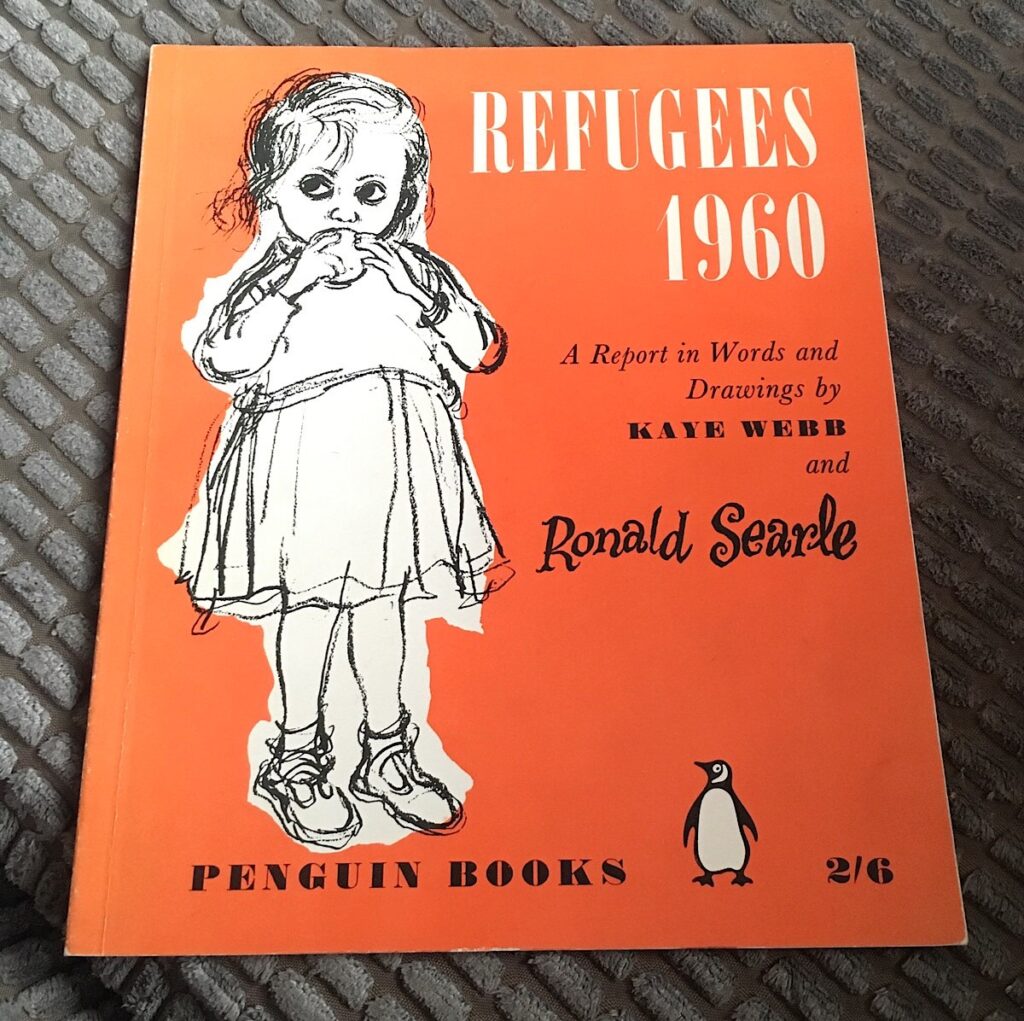

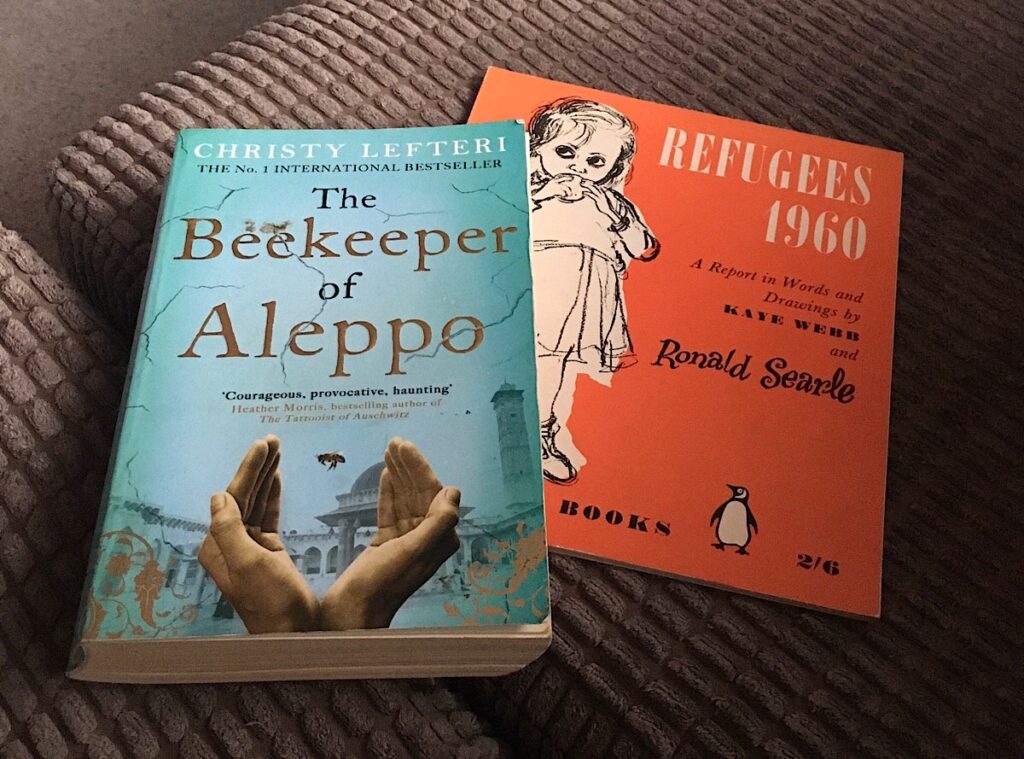

Following up on reading The Beekeeper of Aleppo by Christy Lefteri, a powerful, evocative and pertinent novel focused on the worldwide refugee crisis, I re-read my copy of Refugees 1960: A Report in Words and Pictures by Puffin Club founder Kaye Webb, illustrated by her then husband, Ronald Searle.

(In a similar mood, alongside their superb new graphic novel, Global, available now, I’m planning on re-reading the brilliant award-winning graphic novel, Illegal, reviewed here, by Eoin Colfer, Andrew Donkin and Giovanni Rigano, too).

Published by Penguin Books, Refugees 1960: A Report in Words and Pictures is graphic journalism at its best marking World Refugee Year, an ambitious attempt by the United Nations and by governments, mostly in the First World, including Britain, and Non Government Organisations to increase public awareness of enduring refugee situations. Held from 1st July 1959 to 30th June 1960, the project sought to find solutions such as resettlement or local integration that would improve the lives of refugees around the world, not just in Europe but also in the Middle East, Hong Kong and China.

In addition, it was hoped to improve the visibility of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and to get more governments to sign the 1951 Refugee Convention.

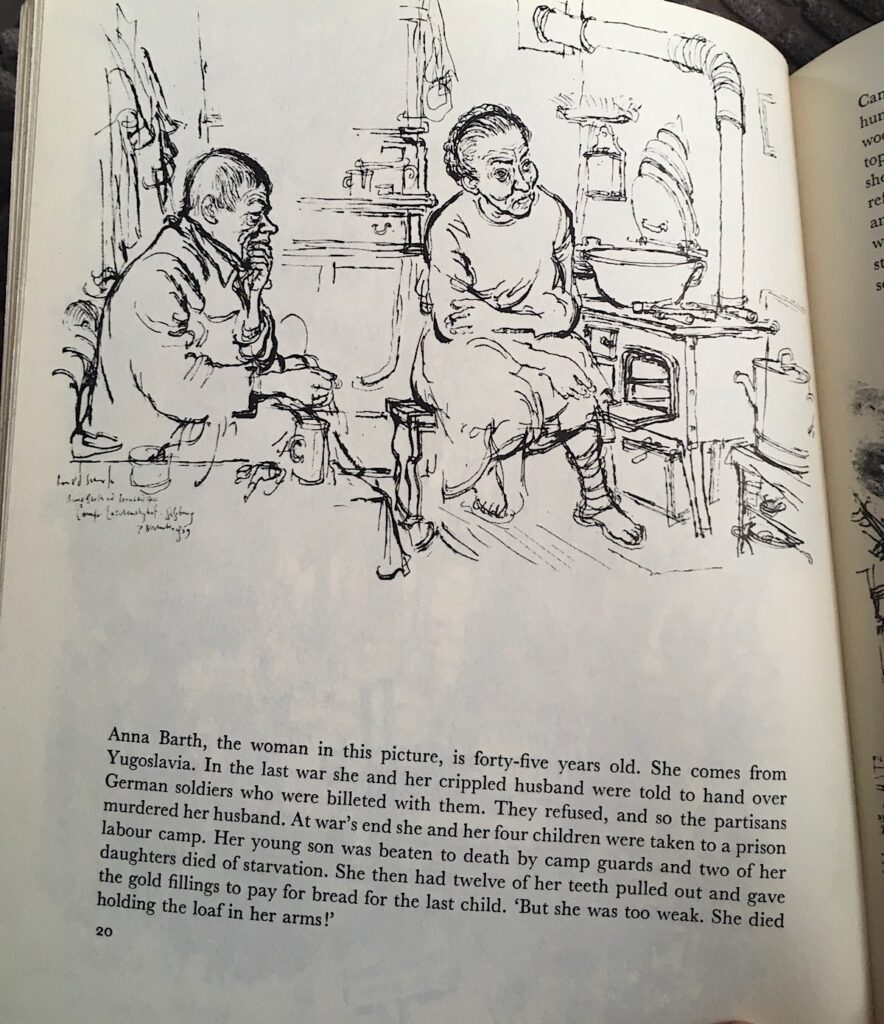

Refugees 1960 is a 48-page collection of drawings, accompanied by carefully worded but on the nail descriptions of conditions post-war refugees found themselves in, victim to massive political change in Eastern Europe, and the ongoing recovery from the cost of World War Two, fifteen years after its end.

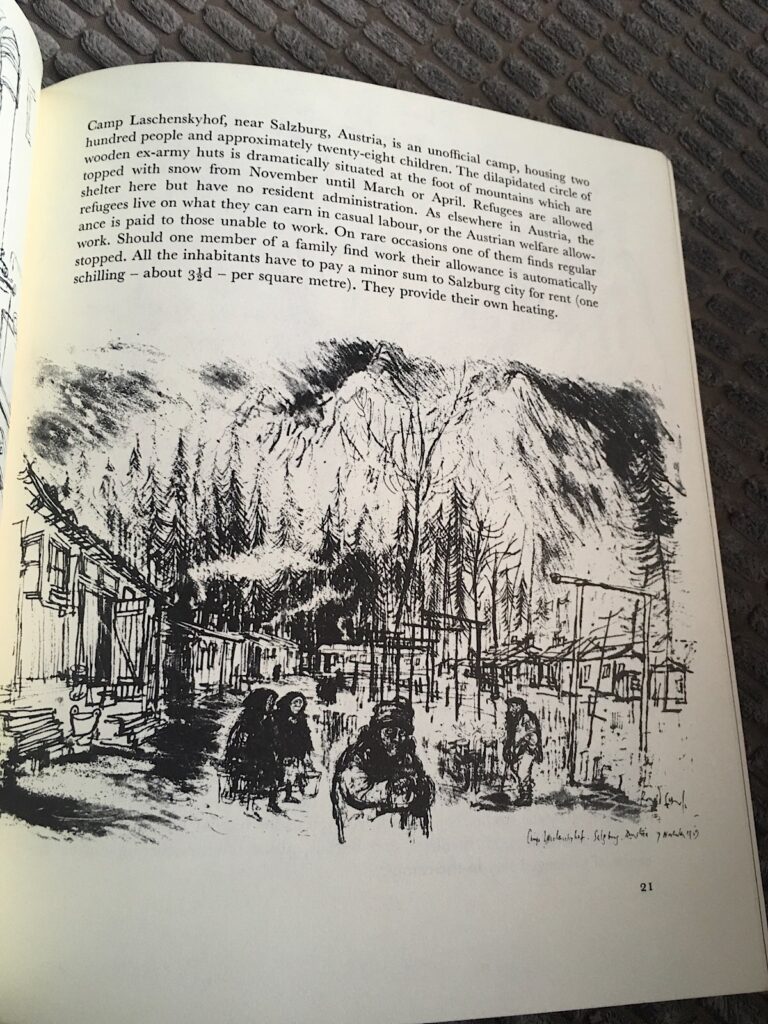

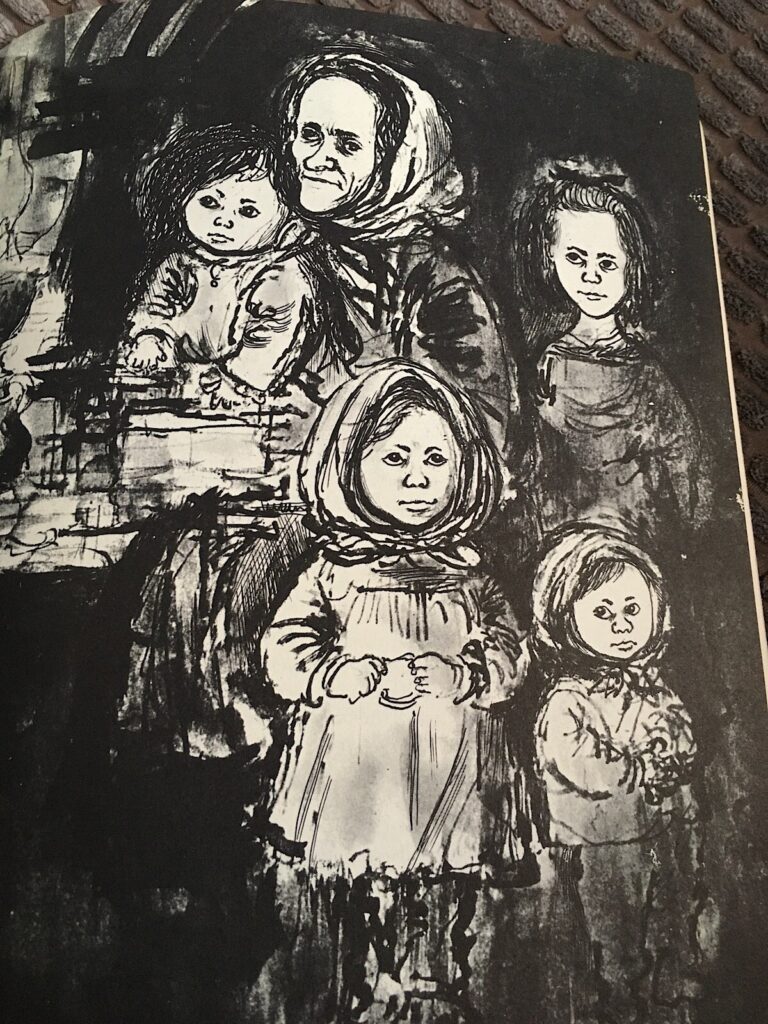

As noted in an introduction to an archive of papers held at the University of Nottingham on the initiative, a particular focus of World Refugee Year was the plight of Displaced Persons and refugees who were still living in camps and other sub-standard accommodation in Germany, Austria, Italy and Greece, 15 years after the end of the war.

More than 60 countries participated in the campaign between June 1959 and June 1960, and Britain played a prominent part, as did other countries including Norway, Sweden, Germany, Canada, the United States, Australia and New Zealand. Soviet bloc countries, however, refused to have anything to do with WRY, on the grounds that the ‘refugee problem’ in Europe could be resolved at a stroke if Western governments did more to encourage Displaced Persons from Eastern Europe to return to their homes.

On the day of the inauguration of World Refugee Year in Britain on 1st June 1959 , the United Kingdom Committee announced a target of two million pounds. Eight months later, after herculean efforts of the committee and its constituent refugee agencies, that sum had been exceeded.

Encouraged by the success of their campaign they doubled the national target to four million pounds. At that point there were still 110,000 refugees left in Europe alone, of whom 22,000 under the mandate of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees were “mouldering away” in camps, as most of them had been for the last fifteen years.

“We have tried, first, to create a climate of opinion throughout the country which would arouse interest in this problem and gain as much support as possible from the public,” noted Katharine Elliot, Baroness Elliot of Harwood in Parliament, initiating debate on the increase in funding on 2nd February 1960.

“Secondly, we have tried to co-ordinate and to encourage a very diverse approach to the subject through innumerable organisations of all kinds; through all the political Parties, through the trade union movement, through the Civil Service and through a vast variety of societies and organisations throughout the whole country— and a really remarkable response has come from everywhere.”

According to the UN office for WRY, public opinion had become familiar with refugees in the abstract: “through frequent repetition, the word ‘refugee’ had come to lose much of its poignancy, and there was little personal knowledge of the plight and sufferings of refugees beyond the immediate areas where they were living”. World Refugee Year aimed to rectify this situation.

Various initiatives for fundraising were organised, including the publishing of Refugees 1960, which features concise, powerful descriptions of conditions in camps and refugees centres informed by Ronald Searle’s powerful black and white art.

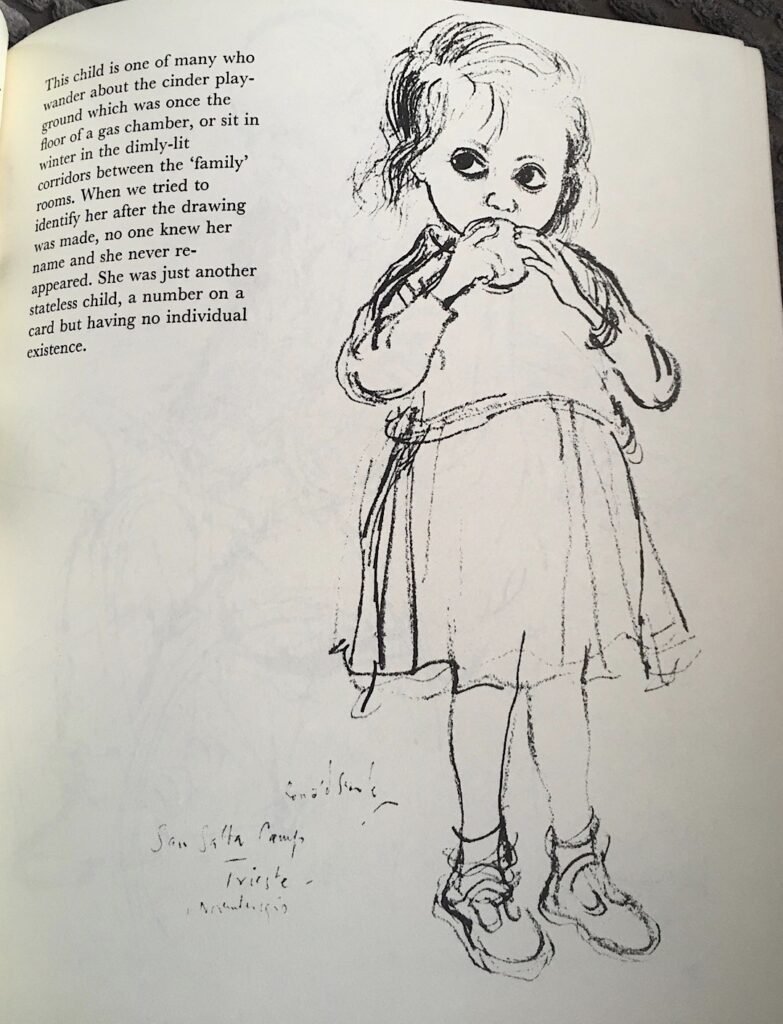

Together, this brilliant husband and wife team deliver a precise barbed arrow highlighting the personal stories of refugees in places like Italy and Greece in the form of graphic journalism, highlighting what was going on across Europe, in centres for refugees that included, as incredible as this may seem today, old Nazi concentration camps.

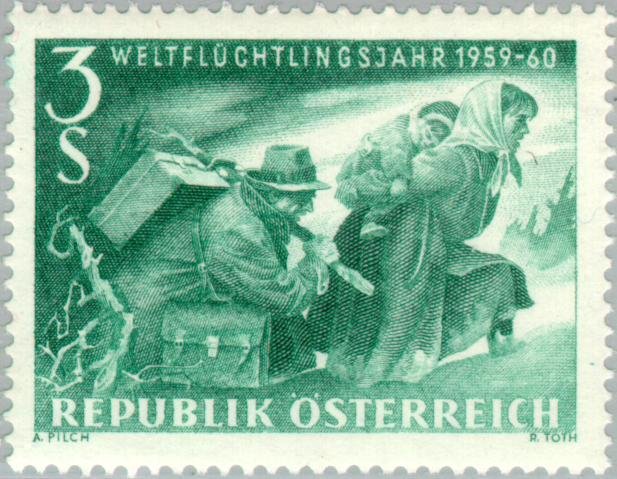

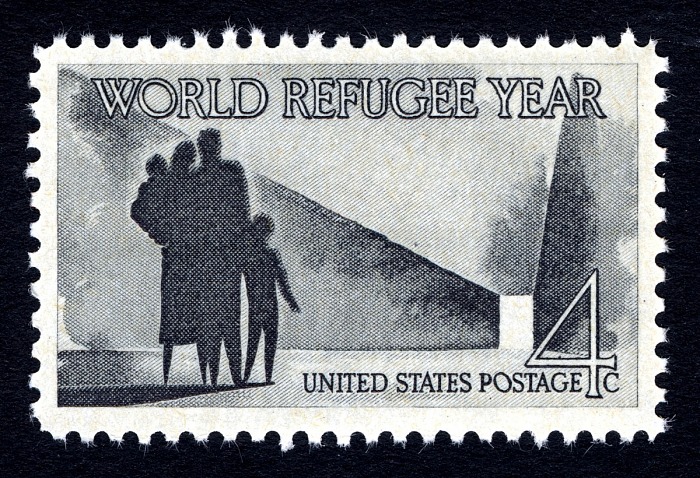

Other projects included the simultaneous issue of first-day covers by seventy postal authorities around the world. But issuing stamps was not just about raising money; it also provided an opportunity to demonstrate attitudes and assumptions about refugees. Austria’s stamp advertised the flight of Hungarians in 1956 and by extension the country’s recent contribution to refugee relief. The US stamp showed a stark wall against which refugees were silhouetted, ‘facing (as the publicity stated) down a long dark corridor towards a bright exit, symbolising escape from the darkness of want and oppression into the brightness of a new life’.

The imagery reinforced the point that the campaign would enable refugees to replace despair with hope, to be moved them from the deplorable camp to comfortable and modern conditions. WRY stamps allowed “the refugee story [to be] told, a story always beginning with flight and despair, and ending, sometimes, in hope and resettlement”.

In addition to stamps, films and photos played a vital part in drawing attention to the plight of refugees and to the assistance provided by the UN and non- governmental organisations in removing them from camps and placing them in decent accommodation. The UN told stories of refugees who had lost hope, but who could thanks to WRY now anticipate a better future.

One powerful image designed to launch the campaign showed a young refugee girl – on the next page was an advert for a package holiday, making a contrast between desperate poverty and pleasurable consumption.

By the 1960s most camps for the “hard core” had been closed, and DPs were either resettled or moved to more modern accommodation. The profile of the UNHCR was enhanced. The British government described it as “the most universal short-term humanitarian enterprise the world has yet seen”.

There were utopian elements to the campaign, although it soon dawned on participants that new refugee crises were beginning to emerge, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, an issue that still resonates today, as Sudan falls into civil war and environmental crisis hits the Democratic Republic of Congo again, hit by devastating floods.

Furthermore, although Palestinian refugees and Tibetan refugees received some relief packages and funds for various projects, the campaign did not, and was not designed to, meet their basic aspirations for the restitution of their “homeland”.

Although WRY did not offer permanent solutions, it provided did provide an opportunity for members of the public to understand something of the struggles faced by refugees on a daily basis, an initiative that seems very much at odds with the rhetoric and policies of some governments today, including our own.

“Nothing is easier than considering the refugees after a while as a pest or as troublesome aliens,” noted the UNHCR representative in Austria of the day. “In reality they are neither heroes nor inferior individuals. They are quite ordinary people like everybody else, but they are living in extraordinary conditions”.

• Copies of Refugees 1960: A Report in Words and Pictures are occasionally offered on auction sites, but you can find them very cheaply in some cases, through third party sellers on AmazonUK, too (Affiliate Link), and through secondhand bookseller sites

• The Beekeeper of Aleppo by Christy Lefteri is available from all good bookshops ISBN: 978-1838770013 | AmazonUK (Affiliate Link) | Bookshop.org (Affiliate Link)

Nuri is a beekeeper; his wife, Afra, an artist. They live a simple life, rich in family and friends, in the beautiful Syrian city of Aleppo – until the unthinkable happens. When all they care for is destroyed by war, they are forced to escape.

As Nuri and Afra travel through a broken world, they must confront not only the pain of their own unspeakable loss, but dangers that would overwhelm the bravest of souls. Above all – and perhaps this is the hardest thing they face – they must journey to find each other again…

• The Beekeeper of Aleppo stage play produced by the Nottingham Playhouse in association with Liverpool Everyman and Playhouse, adapted for the stage by Nesrin Alrefaai and Matthew Spangler, is currently on tour, check the official site for forthcoming dates

Web Links

• The University of Nottingham: When the war was over: European refugees after 1945

A series of briefing papers based on a research project, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, and conducted by historians at the University of Manchester and the University of Nottingham on East European population displacement and resettlement after the Second World War.

• United Nations records for World Refugee Year

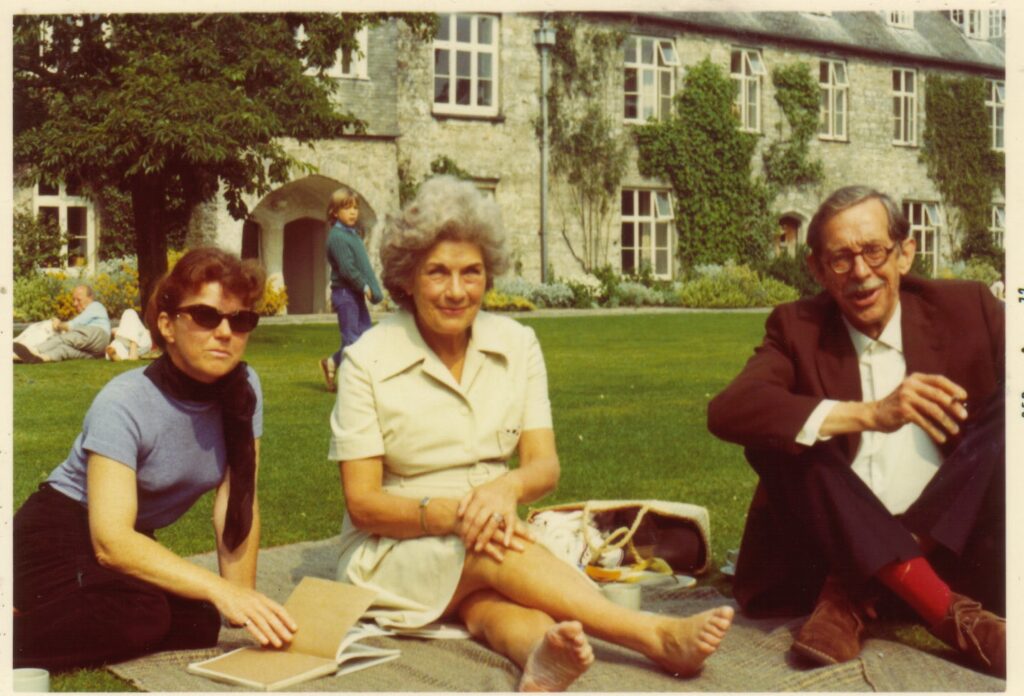

Kaye Webb MBE (26th January 1914 – 16th January 1996), was an editor and publisher who, early in her career worked on titles such as Mickey Mouse Weekly, Lilliput, The Leader, the News Chronicle and Young Elizabethan, and went on to found the Puffin Club in 1967. Her third marriage (1948–1967) was to Ronald Searle, who was the father of her twins, Kate and Johnny.

Webb’s archive and working library are held in the Seven Stories centre for children’s books collection, based in Newcastle upon Tyne.

Prolific and hugely influential, Ronald Searle CBE, RDI (3rd March 1920 – 30th December 2011) was an English artist and satirical cartoonist, comics artist, sculptor, medal designer and illustrator. He is perhaps best remembered as the creator of St Trinian’s School and for his collaboration with Geoffrey Willans on the Molesworth series.

He was a Prisoner of War of the Japanese during World War Two, his surviving drawings of the harrowing experience published in Ronald Searle: To the Kwai and Back, War Drawings 1939–1945, published in 2006. He also served as a courtroom artist at the Nuremberg trials, and the Adolf Eichmann trial in 1961.

Shortly before his death, as we reported back in 2012, he gave about 2200 of his works as permanent loans to the Wilhelm Busch Museum, in Hanover, Germany, now renamed Deutsches Museum für Karikatur und Zeichenkunst. Previously the summer palace of George I of Hanover, this museum also holds Searle’s archives. The Ronald Searle Archive is available to researchers and other interested people by prior appointment.

• See also: The Ronald Searle Tribute Blog | Ronald Searle art for sale at ronaldsearle.co.uk

• Other books by Kaye Webb and Ronald Searle on AmazonUK (Affiliate Link)

The founder of downthetubes, which he established in 1998. John works as a comics and magazine editor, writer, and on promotional work for the Lakes International Comic Art Festival. He is currently editor of Star Trek Explorer, published by Titan – his third tour of duty on the title originally titled Star Trek Magazine.

Working in British comics publishing since the 1980s, his credits include editor of titles such as Doctor Who Magazine, Babylon 5 Magazine, and more. He also edited the comics anthology STRIP Magazine and edited several audio comics for ROK Comics. He has also edited several comic collections, including volumes of “Charley’s War” and “Dan Dare”.

He’s the writer of “Pilgrim: Secrets and Lies” for B7 Comics; “Crucible”, a creator-owned project with 2000AD artist Smuzz; and “Death Duty” and “Skow Dogs” with Dave Hailwood.

Categories: Art and Illustration, Books, Features, Other Worlds

In Memoriam: Comic Artist and illustrator Andrew Chiu

In Memoriam: Comic Artist and illustrator Andrew Chiu  In Review: Timeslides: The Doctor Who Artwork of Colin Howard

In Review: Timeslides: The Doctor Who Artwork of Colin Howard  In Review: Moebius’ Little Pantheon: Arzak available now

In Review: Moebius’ Little Pantheon: Arzak available now  In Review: The Illustrated Journey: A Visual Celebration of Doctor Who

In Review: The Illustrated Journey: A Visual Celebration of Doctor Who

John, I really enjoyed this piece of writing (despite the topic being grim). Your best yet.

Thank you. Feedback always appreciated!