Leonard Matthews, General Managing Editor of Fleetway and the Eagle Group of Comics, was a “Creative Visionary”… but that, Roger Perry argues in his extensive biography of the man which continues here on downthetubes, is only due to him having utilised the ideas of others.

Here, Roger explores his relationship with one particular creator… the man who did most to create Dan Dare…

Frank Hampson – A Thorn in Matthews’ Side

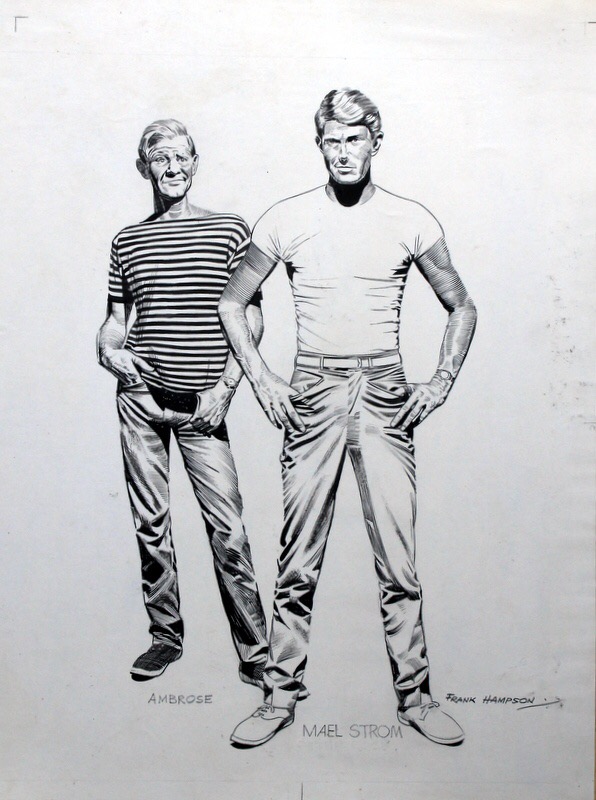

Pictured: Dan Lloyd, Ellen Vincent, Frank Hampson and Derek Lord, as they were in the 1960s and in later life. Dan is still with us!

1962

Despite Leonard Matthews having been conspicuous by his absence, every now and then there would be a reminder of his unseen influence… even though these had been on the periphery of our co-existence. For example, on 1st May, although it ought to have run for a further eleven months – up until 31st March 1963 – we got to hear that the contract Odhams (Longacre Press) had had with Frank Hampson (as orchestrated by the Reverend Marcus Morris prior to his own departure three years earlier) had been prematurely terminated. (This could not have pleased Hampson… in fact, it came back on the grapevine that Hampson had had this on-going grouse that he’d been unfairly treated). But in placing down some of the known facts about all this, I’m not entirely sure that he had been. In order to let you in on some of the other things I know about Hampson, I now ask that you allow me to jump ahead four years – this being to June of 1966.

Having left the confines of 96 Long Acre far behind – where Eagle’s own unhappy association with Frank Hampson had fairly successfully been swept under the carpet – I found myself back in the Fleet Street area and working for Century 21 Publishing. I’d been employed there as Art Editor for the book section, and my immediate boss – Robert T Prior, also known as “Bob” Prior – brought to my notice the fact that during the previous year, Hampson had been approached to work first on TV Century 21 and then on to the forthcoming – but not yet published – Lady Penelope comic. But it would appear that Hampson had already been creating mayhem with his eccentric demands for added this and extra that, with the outcome that my new bosses had ended a situation that perhaps would be best if it was not spoken about.

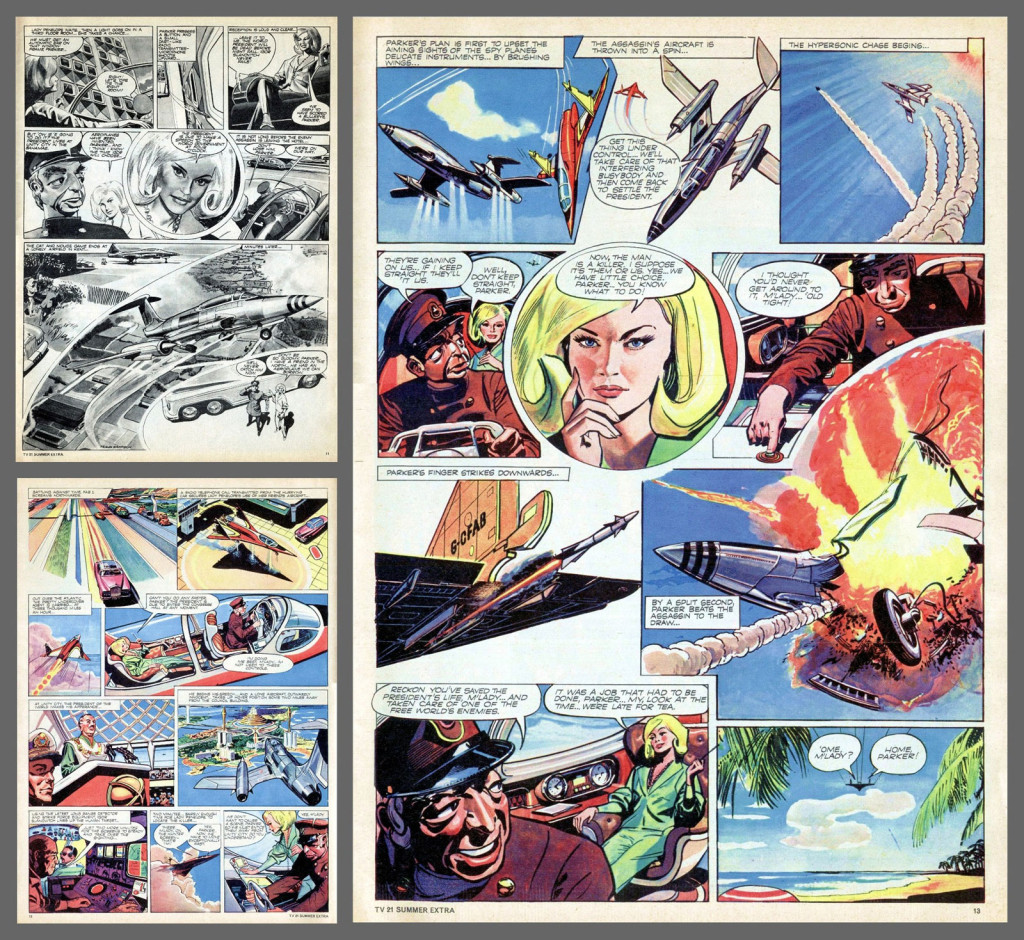

This latest fiasco had begun innocently enough, with Eric Eden having been landed a plum commission to produce a two-page colour feature that homed in on the exploits of Lady Penelope. Quite possibly during the preliminary stages, there had been heavy hints coming from Eden, whereby he had been divulging the fact that Hampson was free and was therefore looking for work. TV Century 21 Managing Editor Alan Fennell has been quoted elsewhere as having said that he didn’t care how long it took him, but he was determined to get the best artists available. Over time, he acquired the services of many leading comic artists of the time (placed here alphabetically), including Frank Bellamy, John Cooper, Eric Eden, Gerry Embledon, Rab Hamilton, Don Harley, Mike Noble, Ron Turner and Keith Watson.

With the mention of Frank Hampson, despite a certain amount of hesitancy by Alan and Art Editor Dennis Hooper, who were aware of Hampson’s health hazard history and what it had entailed – they took the bull by the horns and tentatively approached him to illustrate a four-page strip that was intended for the TV Century 21 Summer Extra. The work – when it came in – had been done to absolute perfection.

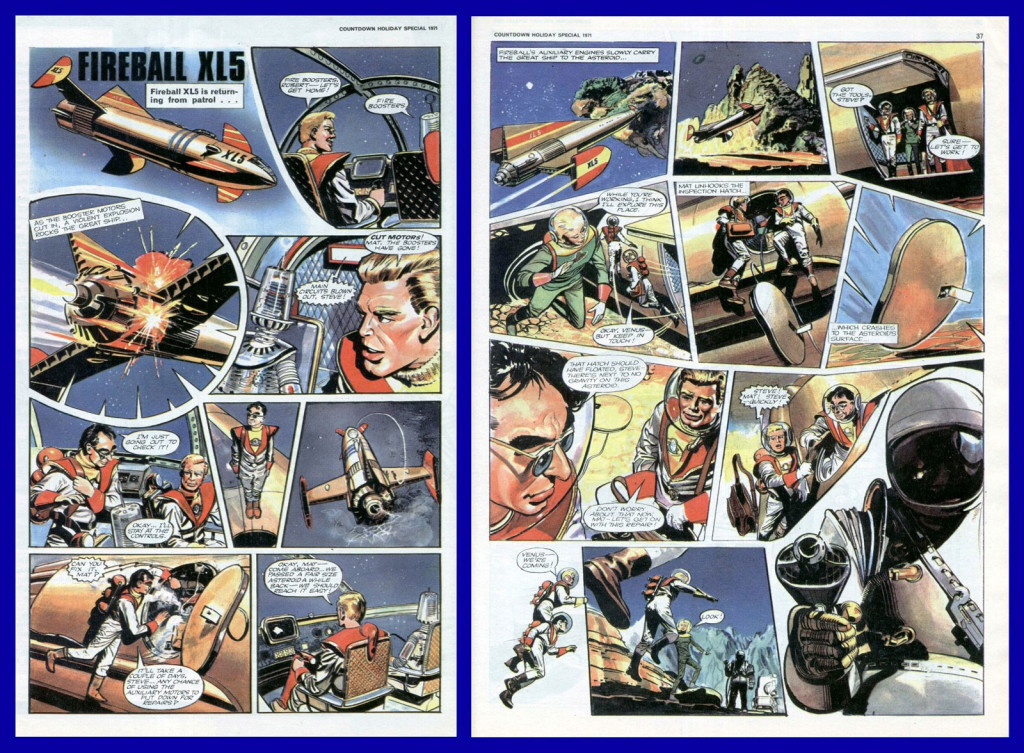

Following on from this, Hampson was then assigned to work on a four-part Fireball XL5 adventure story, scheduled in order to provide Mike Noble with a break from his weekly commitment. It was pretty clear that following Hampson’s enforced sabbatical, now that he had returned to the realms of space-travel once more, he’d tackled the commission with confidence and enthusiasm.

As Fennell and Hooper had been delighted with the end result, it was further proposed that Hampson should now be commissioned to illustrate the colour centre-spread of the new Lady Penelope comic (scheduled to be launched on 22nd January 1966). All had gone well at the preliminary stages: Frank had visited the film studios in Slough to gather research material and to take additional photographic reference shots; and the fears that Fennell and Hooper had had in regard to possible problems were obviously quite unfounded.

However, sometime around late-November (this being still two months prior to the launch), David Slinn clearly recalls Bob Prior showing him the completed cover artwork for a Lady Penelope Annual (for Bob was now in charge of the books and annuals section for Century 21 Publishing’s expanding output). David has said that there were some other related visuals that had also been created by Hampson.

Whether he had actually reached the finished artwork stage by this time or not is unclear, but owing to the fact that he was clearly anxious to turn in something really impressive, Hampson mooted the undoubted benefits that the services of an assistant artist would bring to this prestigious new strip. With Dennis Hooper knowing all too well Frank Hampson’s track record, he’d firmly told Frank that he could have as many assistants as he liked… but that the work would remain within the stipulated (and already agreed) fee (particularly as in Dennis’s estimation, the amount offered per page had certainly been generous enough for Hampson to have paid for his own Epsom-hired help – should he wish to go down that particular route that is).

The recurrence of considered wasteful extras left a sour taste and quickly put the mockers onto wanting to associate with Hampson further – the outcome having been that he was dropped from the project altogether. Another Frank – this one being Frank Langford – was hurriedly enlisted to take Hampson’s place. But was the suggestion of Hampson wanting to employ an assistant enough to warrant him having been taken off the project? I ask you to have a think about this when you have had a chance to read the following piece:

In Eagle Daze Part One, you will have read that I have spoken of Sir Edward Hulton’s growing irritation over the exorbitant cost of producing Eagle and that the items actually specified had been the inexplicably inflated over-spending by Eagle staff for ridiculously expensive lunches; the cost of restocking Marcus Morris’s drinks’ refrigerator; and in particular, pricey telephone calls plus the high usage of electricity – all of which had been mentioned elsewhere in passing. Although it was never mentioned as such, one does have to wonder whether the antics of the Frank Hampson studio (and in particular, Frank Hampson) hadn’t had something to do with it.

In 1956, British Pathé produced a short film for Pathe News, shown in cinemas, showing Frank Hampson at work, along with two male models, one of whom is his father, Robert Hampson who took on the role of Sir Hubert Guest, who is kitted out in a very smart Space-Fleet uniform . The other is Eric Eden (not physically working at his designated role of an assistant artist but is prancing about in a specially-made red space-suit).

It is more than likely that these items had to be specially made (and one-off items such as these don’t come cheap). Secondly, Hampson is often seen surrounded by Dan Dare Artefacts that again have had to have been specially made by someone. All these things cost money and (again most likely) had been reimbursed through filling in an “expenses claim” form.

The top picture of my montage of images from this footage, together with the one at bottom left, shows a model of a space-ship which I judge to be five or six feet from nose-cone to tail. What do you think something like that would have cost? I ask you to put yourself in Sir Edward’s place for a moment. How would you feel about having to pay for all these extraneous (but completely unnecessary) items… wonderful as they undoubtedly are?

Not long after I joined Juvenile Publications on Monday 29th August 1961, Ron Morley had enlightened me by saying: Don’t mention Hampson’s name here. He went on to tell me that not only were there scale models of the various spacecraft made but when it came to having one in a damaged and exploded state, Hampson had not been shy in punching the craft on the spaceship’s nose with his fist before placing it onto the Grant Projector’s flat display platform, so that he might trace off an accurate representation of how the exploded damage looked.

To my way of thinking, these things had cost infinitely more than any of Sir Edward’s quoted pricy telephone calls and the exorbitantly high usage of electricity!

Despite all his faults, there is no doubt that had it not been for Frank Hampson’s extraordinary talent and skills, Eagle would probably have never ever flown… despite the Reverend Marcus Morris’s determination to produce something quite revolutionary.

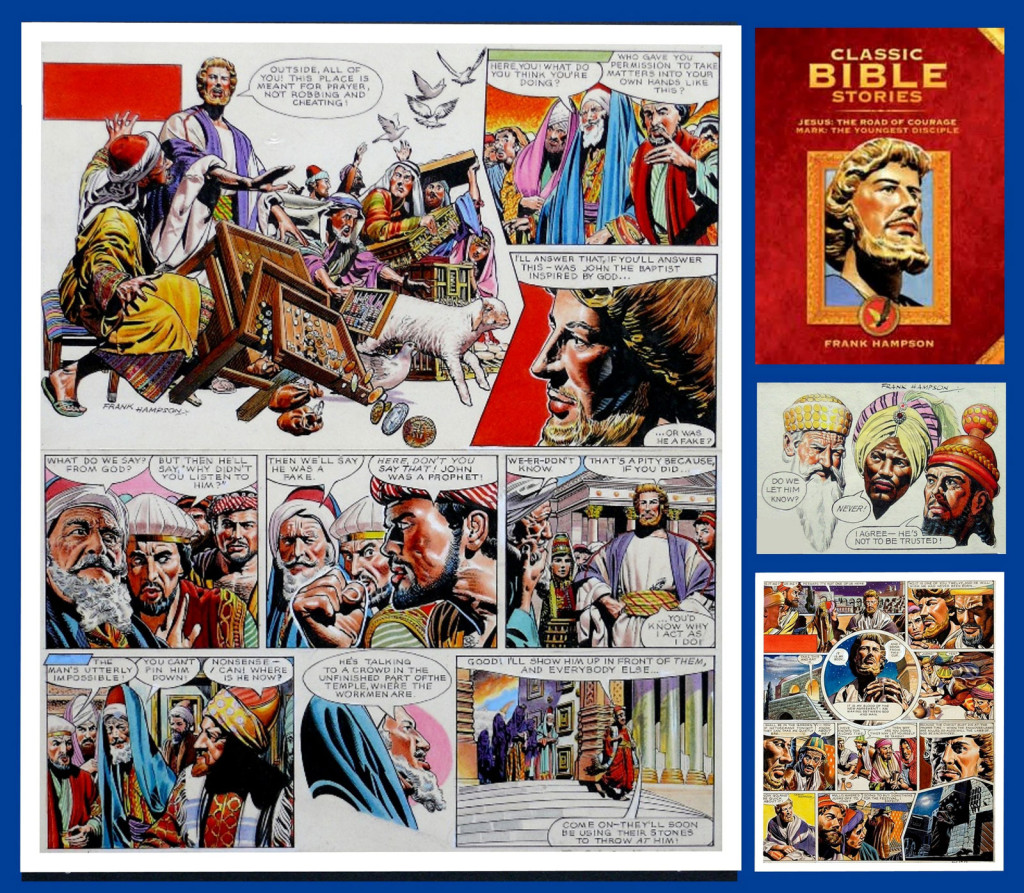

Recapping on what I have already said in earlier parts to this story, in 1959, Frank Hampson had been given a three-month-long vacation so that he might visit the Middle East, including Jerusalem and Palestine, with a number of tours going out to the Dead Sea area thrown in for good measure, to conduct research for the Eagle strip telling the story of Jesus – “The Road of Courage” – a single-page strip chronicle that had begun on 19th March, 1960 and a serial that had appeared weekly on the back page of Eagle for a total of 56 episodes. This trip was subsidised and paid for by Odhams / Longacre Press (this has been spoken of in greater detail in Part Three).

Hampson’s work on “The Road of Courage” was part of a deal that, on top of his “road trip”, meant he was paid a weekly stipend of £60 a week and to make it legal, a four-year contract had been raised. The deal done, Hampson had done all that had been asked of him. But “The Road of Courage” had come to its conclusion at Easter in April 1961. After that, Hampson had continued to receive his £60 a week for doing… precisely nothing. But then, whose fault was that? Nobody at Juvenile Publications had actually asked him to do anything. So why hadn’t they?

There had really been only two people who had had any real contact with Hampson as far as I can see – the first of these had been his decade-long friend and companion Marcus Morris (who as you know, had relinquished his position as General Managing Editor of Eagle et al in August 1959), and the other had been Ellen Vincent. Vincent – up until around April or May of 1959 – had been the Editor of Girl. But having re-married during the early part of 1959, she too had resigned from Juvenile Publications in favour of settling down with her new husband with the view to starting a family… at least, that was the excuse she had given (or perhaps she too had seen the writing on the wall). With Hampson’s two main contacts now gone, who else was left?

As you will have already read in Part Five, Clifford Makins had been having a great many headaches over the Dr James Hemming and the “What’s Your Problem?” page fiasco. So what Frank Hampson was (or indeed wasn’t) actually doing probably never entered his head. Also – and I won’t actually say that the pair had been at each other’s throats – but I have learnt more recently that there hadn’t been much love lost between the pair of them.

Reading between the lines, it would seem that Makins had been keen in letting sleeping dogs lie for the time being. Therefore, he hadn’t been over-zealous in wishing to get in touch.

So what about Eagle’s Art Editor – Charles Pocklington? Why didn’t he get involved and commission Hampson to do something? The answer to that is quite surprising. In an article that appeared in Eagle Times Volume 17 No. 2 Summer 2004, Charles had this to say for himself:

As art editor I was really a studio manager responsible for the production of artwork ready for printing. Frank Hampson I held in high regard as a creative person, but never had the pleasure of meeting him or even spoke to him on the telephone.

Marcus Morris and Ellen Vincent were the two main people to deal with him. Any political infighting did not happen within the precincts of the art or editorial department. The dirty deeds were done at Fleetway management level. I was not privy to these machinations but Derek Lord possibly has more knowledge of the scheming that took place.

Charlie Pocklington’s enlightening admittance had been in reply to an article I had written in Eagle Times Volume 17 No. 1 Spring 2004, in which I had suggested possible reasons for Frank Hampson’s ousting but I have to confess that back then, I had known a good deal less about the ins and out of those dark days than what I have learnt since. In the New Year of 2004 – and prior to my article appearing in Eagle Times – I had written to Dan Lloyd about all this and his reply had also been surprising:

The tortuous sage about Frank Hampson outlined in your e-mail is all news to me. I hadn’t the slightest idea about what was going on or went on: Being an editorial man, I wasn’t privy to the machinations of the art department.

Dan concluded his email by saying:

I’m afraid Derek Lord doesn’t seem to be party to the ins and outs of Hampson’s departure either.

In rounding up this fact-revealing section, I now copy and paste a piece that was included in Eagle Daze Part One (something that I hinted upon just a few moments ago):

On the second or third day at my new place of employ, when I’d spoken of my idol Frank Hampson to co-designer Ron Morley, he’d rapidly drawn in a breath through clenched teeth; had quickly scanned the room to see who else might have been within earshot; and had murmured out of the corner of his mouth:

“Shhh, that’s a dirty name round here… it’d be best if you didn’t mention it!”

Now you all might be thinking that Hampson had been twiddling his thumbs and doing little more than taking time off by relaxing in a deck chair on the back lawn sunning himself – but clearly this was not so. Peter Hampson, Frank’s son recalls that at the time, his father had been working feverishly on a number of strips, many published on Alastair Crompton “Lost Characters” website, although he believes the Modesty Blaise strip was a separate project entirely, and that ‘Dawn O’Dare‘ was also much later.

When Frank Hampson stopped drawing “Dan Dare” and “Road of Courage” for Eagle, he embarked on a number of alternative projects which were never taken up. “Peter Rock” was one of those proposed strips for the Mirror Group. Its relatively ‘finished’ state may indicate that Frank believed that this one would be published. The character was originally going to be called ‘Mael Strom’.

“I remember him drawing ‘Bird Boyd‘ and Birnie,” he recalls. “I think these were all produced without much reference to ‘the management’. I only have some artwork from the “Peter Rock” strip, and that’s up on my website (www.frankhampsonartwork.co.uk).

“This was the one that got furthest in terms of development, but never actually made it into proper publication.”

With both Morris and Vincent having gone off to pastures new, no-one had felt inclined to step in and re-establish contact – it was a case of If we ignore him, perhaps he’ll go away! But there was someone else who’d had no intention of ignoring Hampson.

Frank Hampson had obviously been a thorn in Matthews’ side, for not only had he lost out when he tried to poach him away from Eagle in early 1959 but at the meeting he presided over on Tuesday 5th September, the subject of Frank’s £60 a week stipend was virtually spat out in a rainbow of spittle particles as having been an utter waste of good money. (Mind you, Matthews had made no mention of him having offered Hampson a carrot of £7,500 per annum so that he might poach him away for his own dastardly plans).

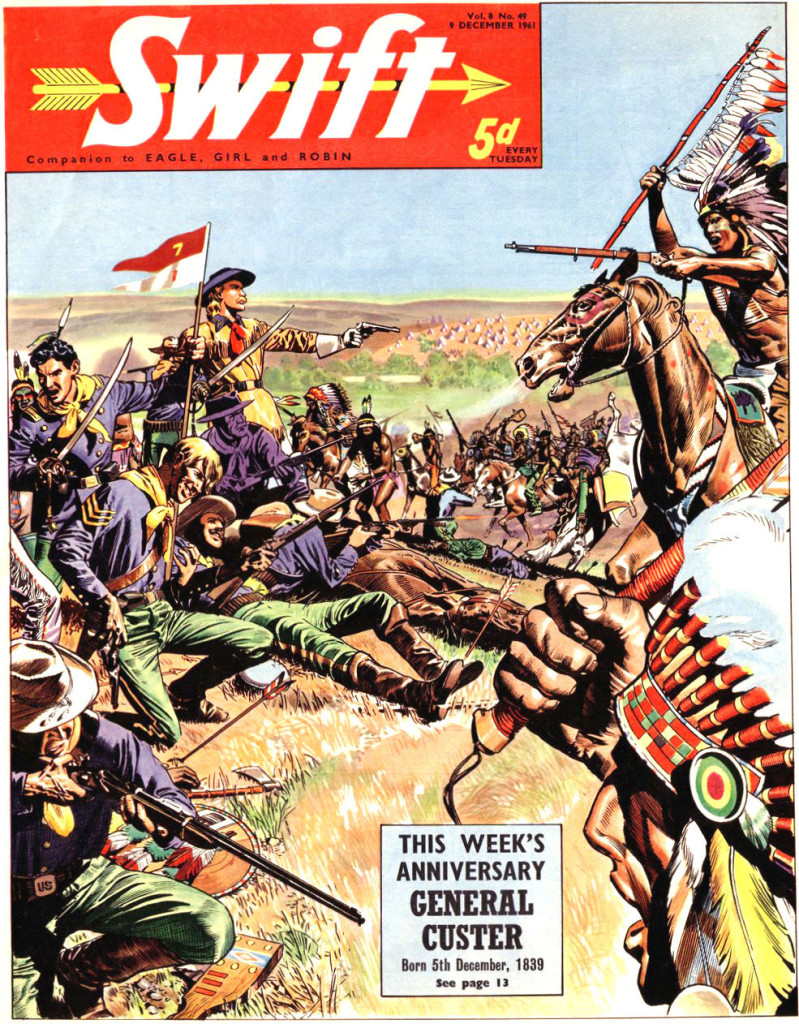

Some time after Charlie Pocklington’s sudden departure on Friday 8th September, 1961, Val Holding (quite possibly having been given the directive by Matthews) had commissioned two front cover illustrations for Swift magazine from Frank Hampson. The first of this pair he’d carried out to perfection, but then (yes, you’ve guessed it) he fell ill again – this time with a peptic ulcer. And so the second cover was passed over to Frank Bellamy for him to complete in Hampson’s place. When Hampson had recovered enough from his latest bout of malaise, instructions for a further cover was sent to the Epsom studio.

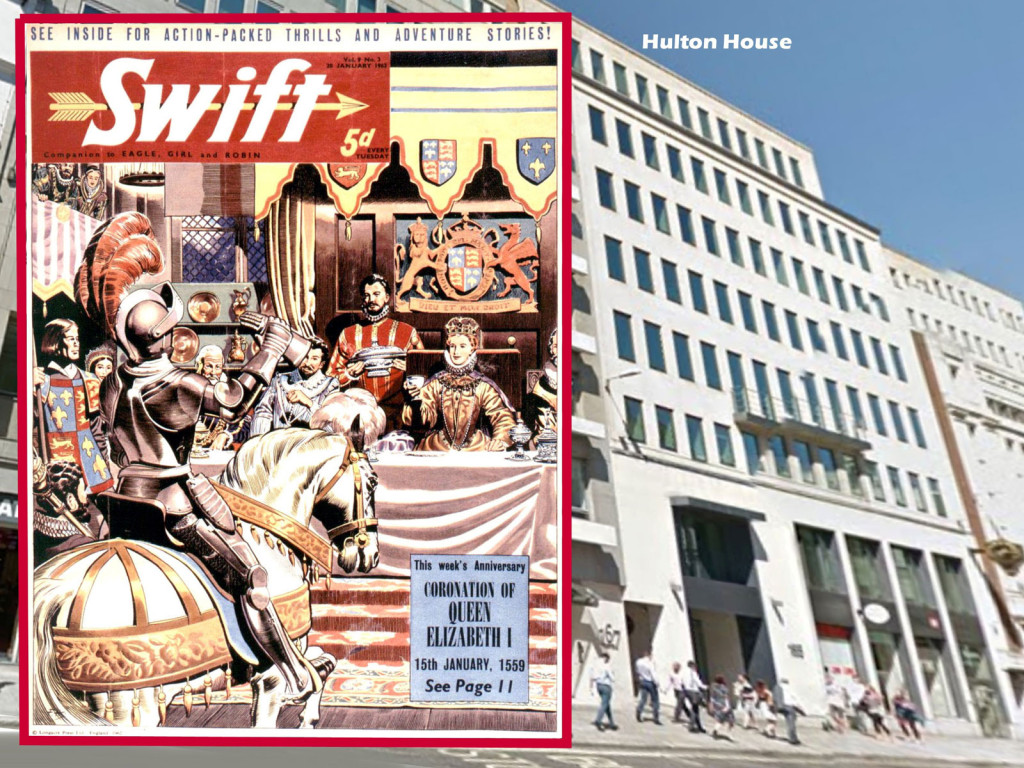

This he completed and I have been told by David Slinn that he delivered the artwork to Hulton House on Friday, 8th December 1961. As to who he saw and where the meeting had taken place is not readily known, for by the 8th of December, the staff of Juvenile Publications had already vacated the Hulton House 5th floor and had been relocated to the Annex building to the building’s rear.

Without any prior warning, Hampson very suddenly had found himself having been confronted by members of the new regime and challenged over what he’d been doing with himself since he’d finished “The Road of Courage” in February (this being nine months earlier). It was, of course, a set-up, contrived by Matthews so that he could lure Hampson away from the safety and seclusion of his Epsom lair… and although he was on familiar territory, he’d now come face-to-face with those complete strangers who were now in control.

In Part Seven, the Mirror hierarchy have other (more pressing) things to think about… a remarriage for one and the death of a spouse for the other… and all the while, Matthews had been feathering his nest and making plans for an early retirement and his future.

Roger Perry

The Philippines

With acknowledgements to David Slinn and to Darren Evens of Eagle Times for producing certain scans used in this article.

[divider]

More Eagle Daze…

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part One

Roger explores the beginnings of the destruction of the Eagle…

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part Two

The comic magazine Top Spot, published in 1958, was Matthews’ brainchild – but it was the male counterpart of an already existing magazine and it was a title that faced plenty of problems as it ran its course before merging with Film Fun after just 58 issues…

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part Three

Roger outlines how Matthews jealousy almost destroyed the Eagle…

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part Four

Roger reveals a possible mole working on the Eagle and trouble behind the scenes on Girl…

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part Five

How a Marks & Spencer Floor Detective Became Managing Editor of Eagle…

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part Six

Roger reveals how Dan Dare co-creator Frank Hampson was thorn in Leonard Matthews side…

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part Seven

Trouble at the top for ‘The Management”, the troubled debut of Boys’ World – and the demise of Ranger

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part Eight

On the creation of Martspress, the company that would publish TV21 in its later, cheaper incarnation…

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part Nine

Moving from the sublime to the ridiculous, Roger recalls how Men Only was given a new lease of life – and Leonard Matthews’ ignorance of Star Wars…

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part Ten

A phone-call out of the blue brings about a closer relationship with the one man Roger had once feared the most…

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part Eleven

A search for elusive promotional film stills end in the middle of nowhere in a one horse town without a horse – and Eagle‘s production methods are recalled

• Eagle Daze: The Life and Times of Leonard James Matthews – Part Twelve

Roger clarifies points made in past chapters, looks back on Leonard Matthews career – and sums up his contribution to British comics – and publishing in general…

[divider]

This article, which is being published in a total of twelve parts, has been put together using material from Leonard Matthews’ obituary as written by George Beal for the Independent newspaper dated Friday, 5th December 1997; also taken from the Independent newspaper dated Sunday, 23rd October 2011 is a piece authored by Jack Adrian (a.k.a. Christopher Lowder); Living with Eagles compiled and written by Sally Morris and Jan Hallwood (particularly pages 219 to 222); David Slinn’s research notes during 2005 in connection with the authoring of Alastair Crompton’s Tomorrow Revisited and from Brian Woodford’s association with Matthews at the Amalgamated Press between 1955 and 1962. Entries also come from both Wikipedia and from the internet under the heading Fleetway Publications.

Further pieces have been taken from Eagle Times as and where identified; the blog-spots of Michael Moorcock’s Miscellany (particularly 9th and 10th April 2013) and Lew Stringer’s Blimey! where he refers to the Top Spot magazine. The remainder is from my own personal association with Leonard Matthews between the years of 1978 and 1991.

• You can read Roger Perry’s full biography here on Bear Alley

Artist, designer, photographer and writer Roger Prölss Perry was the youngest of three children – the given name of Prölss deriving from the maiden name of his paternal German grandmother.

Born in Guildford, Surrey in July 1938, after school he studied at the Regent Street Polytechnic School of Art close to Oxford Circus, the West End and the BBC where he achieved the National Diploma in Arts and Design before commencing with a further year of study in commercial design under the guidance of Ley Kenyon DFC, noted for his writing, art and underwater photography, and lithographer Henry Houghton Trivick (1908-1982).

His first job in the media industry was as an in-house illustrator on Farmers’ Weekly, beginning in March 1959, working under the direction of Art Editor Alfred Harwood, working on the seventh floor of Hulton House at 161-167 Fleet Street, London. He was there for just five months before going into two years of National Service until August 1961, returning to the company (now Long Acre Press) as a layout artist (designer) at “Juvenile Publications”, the umbrella name for Eagle, Girl, Swift and Robin. He joined the team of three other layout artists – Bruce Smith, Ron Morley and John Kingsford – on Monday, 28th August 1961 where he remained until May 1966.

He then began work as Art Editor at Century 21 Publishing until June 1969. As he says: “Yes, I suppose I could be described as a ‘layout artist’ but I commissioned art (Art Editor), kept an eye on Andrew Harrison and Bob Reed (Studio Manager), took photographs as and when needed (Resident Photographer) and generally made sure that everything was present and correct when everything needed was being sent to the printer (Office Boy). I also (with the help of Linda Wheway) came up with the ideas and photographs for five books (Author?)”.

From Century 21 Publishing, Perry then went to Hamlyn Books (July 1969 to October 1970); and worked for Bob Prior’s premium packages for two months before joining ex-Art Editor of Century 21 Publishing Dennis Hooper in December 1970 who was now Editor of Countdown at Polystyle Publications.

Perry remained with Polystyle until September 1974, when he became Art Editor for Purnell Books, remaining with the publisher for eleven years – until 1985 when he started operating his own public relations business.

Due to his growing interest in the art and the close proximity of Bath where the nerve centre of the Royal Photographic Society is, he achieved the distinction of Associate Member in 1987 for audio/ visual presentations thus entitling him to display the letters ARPS after his name… although he rarely does.

Having had a life-long fascination for the Far East, he moved to the Philippines in the 1990s, where he married Marilyn Gesmundo. He lived for 11 years on Cataduanes before moving a number of times recently following Typhoon Haiyan, finally with Raquelyn Navarro in the city of Naga in Cebu.

Sadly, Roger died on 23rd July 2016 following a heart attack, just one day after his 78th birthday.

He is survived by his daughter, Rae. His son, Marcus, predeceased him after a long battle with cancer.

Categories: Creating Comics, Featured News, Features

Rebellion announces new Battle Action mini series – our guide to the returning strips

Rebellion announces new Battle Action mini series – our guide to the returning strips  Comic Creator Spotlight: The Art of Gordon Livingstone

Comic Creator Spotlight: The Art of Gordon Livingstone  The Rotten State of Newsagents – Is it any Wonder Publishers Are Pushing Digital?

The Rotten State of Newsagents – Is it any Wonder Publishers Are Pushing Digital?